Johann Eck facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

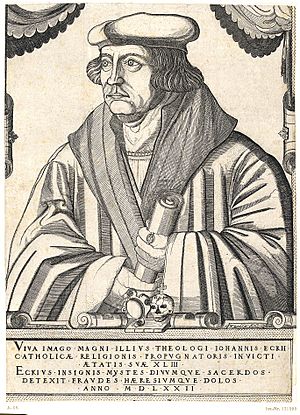

Johann Maier von Eck

|

|

|---|---|

Johann Maier von Eck

|

|

| Born | 13 November 1486 Eck

|

| Died | 10 February 1543 (aged 56) |

| Occupation | German Scholastic theologian, Catholic prelate, and early counterreformer |

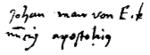

| Signature | |

|

|

Johann Maier von Eck (born November 13, 1486 – died February 10, 1543) was an important German Catholic theologian. He was also known as John Eck. He was a key figure in the Counter-Reformation, which was a time when the Catholic Church tried to reform itself. Eck was one of the main opponents of Martin Luther, a leader of the Protestant Reformation.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Johann Eck was born as Johann Maier in a place called Eck. This village was later known as Egg, near Memmingen in Germany. He added "Eck" to his name because of his birthplace. His father, Michael Maier, was a farmer and a local official.

Johann's uncle, Martin Maier, who was a priest, helped him get an education. At just 12 years old, Johann started studying at the University of Heidelberg. The next year, he moved to the University of Tübingen. By 1501, he earned his master's degree. He then began studying theology, which is the study of religious faith. He also learned about Hebrew and economics.

In 1501, he left Tübingen because of a plague. After a year at the University of Cologne, he settled at Freiburg University. There, he studied theology and law. He later became a successful teacher. One of his students was Balthasar Hubmaier, who became an important leader of the Anabaptist movement. In 1508, Eck became a priest. Two years later, he earned his doctorate in theology.

Life as a Professor

At Freiburg in 1506, Johann Eck published his first work. He was known as a brilliant speaker, but he loved to argue. Because of disagreements with his colleagues, he accepted a job at the University of Ingolstadt in 1510. He became a professor of theology there. He also received honors and income as a church official.

By 1512, he became a leader at the university. He helped make Ingolstadt a strong center for Catholicism. Eck was very knowledgeable and wrote many books. In theology, he wrote Chrysopassus (1514), where he discussed a theory called predestination. He also became known for his comments on important philosophical works.

Eck also studied economics. He argued that it was lawful to charge interest on loans. He successfully defended this view in debates in Augsburg (1514) and Bologna (1515). He also debated about predestination in Vienna in 1516. These successes gained him support from wealthy families like the Fuggers. However, these views upset Martin Luther.

Between 1516 and 1520, Eck wrote many commentaries for university textbooks. He aimed to find a middle ground between old and new ideas in theology.

Eck strongly supported the Pope. His main work, De primatu Petri (1519), defended the Pope's authority. Another important book, Enchiridion locorum communium adversus Lutherum, was printed 46 times between 1525 and 1576. From 1530 to 1535, he published a collection of his writings against Luther. Johann Eck died in Ingolstadt on February 10, 1543.

Debates with Luther

In 1517, Johann Eck and Martin Luther were friendly. Luther even thought Eck agreed with his ideas. However, this friendship did not last long. Eck wrote a paper called Obelisci, attacking Luther's ideas. He accused Luther of supporting a "heresy" and causing problems in the Church. Luther responded to Eck's attacks. Another scholar, Andreas Karlstadt, also defended Luther's views and argued fiercely with Eck.

Eck and Luther both wanted to have a public debate. They agreed that Eck would debate Karlstadt first. In December 1518, Eck published his main points against Karlstadt. But these points were really aimed at Luther. So, Luther declared he was ready to debate Eck himself.

The debate between Eck and Karlstadt began in Leipzig on June 27, 1519. Eck argued that people's free will helps them do good deeds. But Karlstadt made him change his mind, agreeing that God's grace and free will work together. Karlstadt then argued that good deeds come only from God. Eck agreed that free will is passive at the start of conversion. However, he still believed that people's will becomes active later.

Eck managed to confuse Karlstadt and was seen as the winner of this part of the debate. He had a harder time against Luther. The debate between Eck and Luther lasted 23 days (July 4-27). They discussed the Pope's authority, purgatory, and other religious topics. The judges did not give a clear winner. Eck did get Luther to admit that some ideas of the Hussites (a group considered heretical) had truth. Luther also spoke against the Pope. Eck was seen as the victor by the theologians at the University of Leipzig.

Attacks on Reformers

After returning to Ingolstadt, Eck tried to convince Frederick of Saxony to burn Luther's books. In 1519, Eck published eight writings against the new religious movement. However, he failed to get universities to condemn the results of the Leipzig debate. Only the universities of Cologne and Leuven supported Eck.

Luther responded to Eck's attacks with strong words. Around this time, Philipp Melanchthon, another reformer, realized the difference between true Christian theology and the old scholastic ideas. Eck was very annoyed and claimed Melanchthon knew nothing about theology. Melanchthon quickly responded to this claim.

Eck also tried to help Jerome Emser by writing a strong attack against Luther. Two satirical writings, one by Johannes Oecolampadius and another by Willibald Pirckheimer, angered Eck. He wanted all these writings publicly burned in Ingolstadt. However, his colleague Johann Reuchlin stopped him.

Papal Representative

Eck was seen as a brave defender of the Catholic faith in Rome. In Germany, he convinced the universities of Cologne and Leuven to condemn Luther's writings. But he could not get German princes to agree. In January 1520, Pope Leo X invited Eck to Italy. Eck presented his latest work, De primate Petri adversus Ludderum, to the Pope. He was rewarded with a special church title.

In July, Eck returned to Germany with a special paper from the Pope called Exsurge Domine. This paper condemned 41 of Luther's ideas as wrong. Eck thought he could now defeat Luther and his supporters. However, publishing this paper was difficult. Universities and scholars criticized it. Because of public opinion, Eck barely escaped Saxony alive.

In some cities like Meissen and Brandenburg, he managed to announce the Pope's message. But in Leipzig, students made fun of him, and he had to flee at night. In Erfurt, students tore down the paper and threw it in the water.

Eck became very angry and asked Emperor Charles V to take action against Luther. This led to the Edict of Worms in May 1521, which declared Luther an outlaw. In 1521 and 1522, Eck went to Rome again to report on his work. After his second visit, he helped create a religious law in Bavaria in 1522. This law made the University of Ingolstadt a kind of court to investigate heresy. In return, Eck got valuable church benefits for the duke of Bavaria during a third trip to Rome in 1523. He continued his strong efforts against the reformers, publishing eight major works between 1522 and 1526.

Eck also wanted wealth and power. He took the income from his church parish in Günzburg and left the duties to another priest. He went to Rome twice to get permission for an inquisition court against Luther's teachings in Ingolstadt. His first trip in late 1521 was unsuccessful because Pope Leo X died. But his second trip in 1523 succeeded. Eck was involved in many heresy trials, including one against Leonhard Kaser.

Debates with Zwingli's Followers

Besides his work as an inquisitor, Eck published one or more writings each year. These defended Catholic beliefs like the Mass, purgatory, and confession. His book Enchiridion locorum communium adversus Lutherum et alios hostes ecclesiae (1525) was printed 46 times before 1576. It was mainly against Melanchthon's ideas, but it also discussed the teachings of Huldrych Zwingli, another reformer.

From May 21 to June 18, 1526, a public debate was held in Baden-in-Aargau. Eck and Thomas Murner debated against Johann Oecolampadius about the doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ). Eck was seen as the clear winner. He convinced the authorities to actively persecute Zwingli and his followers.

However, Eck's victory at Baden was weakened by the Bern Disputation in January 1528. In this debate, the reformers' ideas were discussed without Eck present. As a result, Bern, Basel, and other places joined the Reformation. At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, Eck was the main Catholic theologian.

Attempts at Peace

For the Diet of Augsburg, Eck gathered 404 ideas from the reformers' writings that he believed were heretical. He did this to help Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

At Augsburg, the Emperor asked Eck and 20 other theologians to write a response to the Lutheran Augsburg Confession. This was a statement of faith presented by the Lutherans on June 25, 1530. Eck had to rewrite it five times before the Emperor was satisfied. This response was called the Confutatio pontificia, and it showed the Catholic Church's reaction to the reformers. Eck also took part in talks with Protestant theologians, including Philipp Melanchthon, but these talks did not lead to peace.

At the Colloquy of Worms in 1540, Eck seemed willing to compromise. In January 1541, he continued these efforts. He even impressed Melanchthon, who thought Eck was ready to agree with the main ideas of the reformers, like justification by faith (being saved by faith alone). But at the Diet of Regensburg in 1541, Eck again strongly opposed the reformers. Afterward, Eck argued with Martin Bucer about Bucer's report on the diet.

Eck's German New Testament

Among Eck's many writings, his German translation of the Bible is notable. This was a revised version of H. Emser's translation of the New Testament. It was first published in Ingolstadt in 1537.

Works

- .

- .

- .

- Eck, Johann (1538), Explanatio Psalmi vigesimi, ed., Bernhard Walde, 1928, Münster in Westfalen: Aschendorff.

See also

In Spanish: Johann Eck para niños

In Spanish: Johann Eck para niños

- Albert of Mainz

- Girolamo Aleandro

- Bartholomaeus Arnoldi von Usingen

- Gabriel Biel

- Thomas Cajetan

- Peter Canisius

- Johann Cochlaeus

- Johann Crotus (Crotus Rubianus)

- Jerome Emser

- John Fisher

- Hochstratus Ovans

- Jacob van Hoogstraten

- John Mair

- Karl von Miltitz

- Thomas More

- Thomas Murner

- William of Ockham

- Ortwin

- Johannes Pfefferkorn

- Johann Reuchlin

- Caspar Schatzgeyer

- Johann Tetzel

- Georg Witzel