Johann Reuchlin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Johann Reuchlin

|

|

|---|---|

|

Johann Reuchlin, woodcut depiction from 1516

|

|

| Born | 29 January 1455 Pforzheim, Margraviate of Baden, Kingdom of Germany, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | 30 June 1522 (aged 67) Stuttgart, Duchy of Württemberg, Kingdom of Germany, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Freiburg University of Orléans University of Poitiers |

| Era | Western philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Renaissance humanism |

| Institutions | University of Ingolstadt |

|

Main interests

|

Ancient Greek, Hebrew, law, Christian mysticism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Christian Kabbalah Reuchlinian pronunciation |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

|

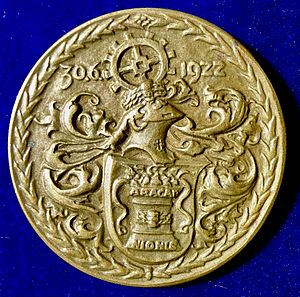

Johann Reuchlin (born January 29, 1455 – died June 30, 1522), sometimes called Johannes, was a German Catholic scholar. He was a key figure in Renaissance humanism, a movement that focused on learning from ancient times. Reuchlin was especially skilled in Greek and Hebrew languages. His work helped spread knowledge of these languages across Germany and other parts of Europe.

Contents

Early Life and Education

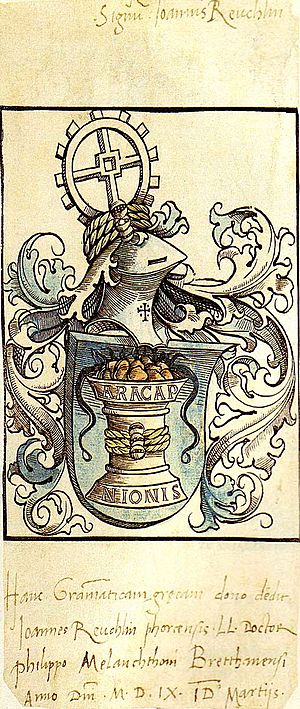

Johann Reuchlin was born in 1455 in Pforzheim, a town in the Black Forest region of Germany. His father worked for a Dominican monastery there. When he was young, his Italian friends gave him the Greek nickname Capnion, which meant "smoke." He liked this name and sometimes used it.

Reuchlin started learning Latin at the monastery school. In 1470, he briefly attended the University of Freiburg, but he didn't learn much there. His life as a scholar really began by chance. He had a beautiful singing voice, which helped him get a place in the home of Charles I, Margrave of Baden-Baden. Soon, because he was good at Latin, he was chosen to travel with Frederick, the prince's third son, to the University of Paris.

This trip changed Reuchlin's life. He began to learn Greek, which had only recently started to be taught in Paris. He also became a student of Jean Heynlin, a respected scholar. In 1474, Reuchlin followed Heynlin to the new University of Basel.

Becoming a Teacher and Writer

At Basel, Reuchlin earned his master's degree in 1477. He started teaching, focusing on a more classical style of Latin than was common then. He also taught about Aristotle using the original Greek texts. He continued his Greek studies under Andronicus Contoblacas. While in Basel, he met a bookseller named Johann Amerbach. For Amerbach, Reuchlin created a Latin dictionary called Vocabularius Breviloquus (1475–76), which became very popular and was printed many times.

Reuchlin soon left Basel to improve his Greek skills further with George Hermonymus in Paris. He also learned to write Greek beautifully so he could earn money by copying old manuscripts. He decided to become a lawyer and studied at the famous law schools of Orléans (1478) and Poitiers, where he finished his law studies in 1481.

In December 1481, Reuchlin went to Tübingen. He wanted to teach at the local university. However, his friends suggested him to Count Eberhard I, Duke of Württemberg. The Count needed an interpreter for a trip to Italy. Reuchlin was chosen for this job. In February 1482, he traveled from Stuttgart to Florence and Rome.

This journey was short, but it allowed Reuchlin to meet many learned Italians, especially at the Medicean Academy in Florence. His connection with Count Eberhard became strong. After returning to Stuttgart, he received important jobs at the Count's court.

Around this time, Reuchlin got married, but not much is known about his family life. He didn't have any children. However, his sister's grandson, Philip Melanchthon, was like a son to him. Later, the Protestant Reformation caused them to drift apart.

In 1490, Reuchlin visited Italy again. He met Pico della Mirandola, a scholar whose ideas about Kabbalah (a mystical Jewish tradition) later influenced Reuchlin. In 1492, he went on a diplomatic trip to see Emperor Frederick in Linz. There, he began to learn Hebrew from the Emperor's Jewish doctor, Jakob ben Jehiel Loans. This was the start of his deep knowledge of Hebrew. He improved his Hebrew even more during his third visit to Rome in 1498. In 1494, his book De Verbo Mirifico greatly increased his fame.

In 1496, Duke Eberhard I of Württemberg died. Reuchlin's enemies gained influence with the new ruler, Duke Heinrich. So, Reuchlin was happy to accept an invitation from Johann von Dalberg, the scholarly bishop of Worms. He moved to Heidelberg, a center for scholars. Reuchlin's job there was to translate Greek texts. Even though he wasn't a public university professor for much of his life, Reuchlin was the main person teaching Greek and Hebrew in Germany. He created many learning tools for students. He also taught a specific way of pronouncing Greek, which became known as the Reuchlinian pronunciation.

At Heidelberg, Reuchlin had many private students. He was not popular with the monks, who often disagreed with his ideas. He even wrote a Latin comedy called Sergius, which made fun of monks and fake religious relics. Through Dalberg, Reuchlin met Philip, Count Palatine of the Rhine, who asked him to guide his sons' studies. In 1498, Philip sent Reuchlin on the important trip to Rome where he furthered his Hebrew studies.

Reuchlin returned from Rome with many Hebrew books. He found that the government in Stuttgart had changed, allowing him to return home to his wife. His friends were now in power and recognized his value. Around 1500 or 1502, he received a very important legal position in the Swabian League. He held this job until 1512, when he retired to a small estate near Stuttgart.

Hebrew Studies and the Book Controversy

For many years, Reuchlin became more and more interested in Hebrew studies. For him, it wasn't just about language; it was also about understanding the Bible better. He believed the Vulgate (the common Latin Bible translation) wasn't enough. He wanted to understand the original Hebrew texts.

Reuchlin learned from medieval rabbis, especially David Kimhi. Once he understood their teachings, he wanted to share this knowledge with others. In 1506, he published his very important book, De Rudimentis Hebraicis. This book was a Hebrew grammar and dictionary, mostly based on Kimhi's work. It was expensive and sold slowly. It was also hard to get Hebrew Bibles in Germany because of wars. Reuchlin helped by printing the Penitential Psalms with explanations in 1512.

Reuchlin was also interested in mystical ideas, especially the Kabbalah. Like Pico della Mirandola, he believed that Kabbalah contained deep wisdom that could help defend Christianity and connect science with religious mysteries. He wrote about these ideas in De Verbo Mirifico and later in De Arte Cabbalistica (1517).

Many people at the time thought that to convert Jewish people to Christianity, their books should be taken away. Johannes Pfefferkorn, a German Catholic theologian who had converted from Judaism, strongly supported this idea. He preached against Jewish people and tried to destroy copies of the Talmud (a central text of Jewish law and tradition). Pfefferkorn believed that Jewish people wouldn't convert because of usury (lending money at high interest), not being forced to attend Christian sermons, and honoring the Talmud.

Pfefferkorn's plans were supported by the Dominicans in Cologne. In 1509, he got permission from the Emperor to take all Jewish books that were against the Christian faith. He went to Stuttgart and asked Reuchlin, as a lawyer and expert, to help him carry out this order. Reuchlin avoided helping, partly because the order wasn't quite official. But he couldn't stay out of the conflict for long. Pfefferkorn's actions led to problems and a new appeal to Emperor Maximilian.

In 1510, Emperor Maximilian asked Reuchlin to join a group reviewing the matter. Reuchlin's answer, dated October 6, 1510, was very important. He divided Jewish books into six types (not including the Bible, which no one wanted to destroy). He showed that very few books actually insulted Christianity, and most Jewish people didn't value those few. Other books were necessary for Jewish worship, which was allowed by law. Still others contained valuable scholarly information that shouldn't be destroyed just because they were part of another faith. Reuchlin suggested that the Emperor should order two Hebrew teaching positions at every German university for ten years, and Jewish communities should provide the books.

Other experts suggested taking all books from Jewish people. When the Emperor hesitated, Reuchlin's opponents blamed him for their lack of success. In 1511, Pfefferkorn spread a false accusation at the Frankfurt Fair, claiming Reuchlin had been bribed. Reuchlin defended himself in a pamphlet called Augenspiegel (meaning "Eyeglass" or "Spectacles"). The theologians at the University of Cologne tried to stop its publication. On October 7, 1512, they, along with the inquisitor Jacob van Hoogstraaten, got an imperial order to take away all copies of Augenspiegel.

In 1513, Reuchlin was called before a court of the inquisition. He was willing to learn about theology, which wasn't his main subject. But he would not take back what he had said. As his enemies pushed him, he openly challenged them in a book called Defensio contra Calumniatores (1513). Universities were asked for their opinions, and most were against Reuchlin. Even Paris (in August 1514) condemned Augenspiegel and told Reuchlin to change his mind. Meanwhile, a formal trial began in Mainz. But Reuchlin managed to have the case moved to the church court in Speyer.

The "Reuchlin affair" caused a big split in the church. Eventually, the case went to the Pope's court in Rome. The final decision wasn't made until July 1516. Although the decision was mostly in Reuchlin's favor, the trial was simply canceled.

While Reuchlin's opponents (called "obscurantists" because they tried to block new learning) got off easily in Rome, they faced a huge blow in Germany. To defend Reuchlin, a book called Virorum Epistolæ Clarorum ad Reuchlinum Phorcensem (Letters of famous men to Reuchlin of Pforzheim) was published. This was quickly followed by Epistolæ Obscurorum Virorum (Letters of obscure men). This second book was a collection of satirical letters that pretended to defend Reuchlin's accusers, but actually made fun of them. No group could survive the ridicule that this book poured on Reuchlin's opponents.

Ulrich von Hutten and Franz von Sickingen tried to force Reuchlin's enemies to pay him back for his financial losses. They even threatened to fight against the Dominicans of Cologne and Speyer. In 1520, a group met in Frankfurt to look into the case. It condemned Hoogstraaten. But the final decision from Rome did not pay Reuchlin back. The conflict ended, however, as public interest shifted to the Lutheran question. Reuchlin no longer feared new attacks. When he heard about Luther's ideas in 1517, he said, "Thanks be to God, at last they have found a man who will give them so much to do that they will be compelled to let my old age end in peace."

Some historians believe this conflict helped start the Protestant Reformation. Even though some suspected him of leaning towards Protestantism, Reuchlin never left the Catholic Church. In 1518, he was offered a job as a professor of Hebrew and Greek at Wittenberg, but he sent his nephew Philip Melanchthon instead.

End of Life

Reuchlin did not enjoy his victory over his accusers for very long. In 1519, Stuttgart suffered from famine, civil war, and a terrible sickness called the plague. From November 1519 to spring 1521, Reuchlin found safety at the University of Ingolstadt. There, he was appointed a professor by William of Bavaria. He taught Greek and Hebrew for a year. It had been 41 years since he last taught publicly at Poitiers. But even at 65, he was still a great teacher, and hundreds of students came to learn from him.

This peaceful time was again broken by the plague. Reuchlin was called to Tübingen and spent the winter of 1521–22 teaching there. In the spring, he needed to visit the baths of Liebenzell for his health. There, he caught jaundice, a liver illness, and died from it.

Johann Reuchlin died in Stuttgart on June 30, 1522. He is buried at St. Leonhard church. His name is remembered as one of the most important scholars of the new learning, second only to his younger contemporary, Erasmus.

See also

In Spanish: Johannes Reuchlin para niños

In Spanish: Johannes Reuchlin para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |