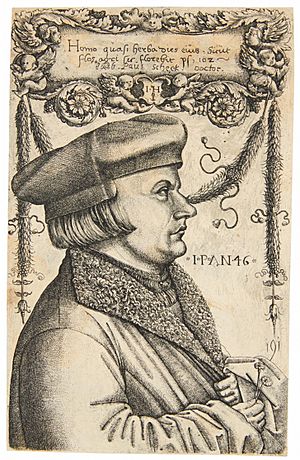

Johannes Pfefferkorn facts for kids

Johannes Pfefferkorn (born Joseph in 1469 in Nuremberg, died October 22, 1521, in Cologne) was a German writer and theologian. He was born Jewish but later became a Catholic Christian. Pfefferkorn became known for speaking out against Jewish people and trying to destroy their religious books, especially the Talmud. He also had a long public argument with a scholar named Johann Reuchlin.

Contents

Pfefferkorn's Early Life

Johannes Pfefferkorn was born Jewish, probably in Nuremberg. He lived in Nuremberg for some time before moving to Cologne. In 1504, he faced legal trouble and was released from prison. The next year, in 1505, he decided to become a Christian. He was baptized into the Catholic Church along with his family.

Pfefferkorn's Views on Jewish Writings

After his conversion, Pfefferkorn became an assistant to Jacob van Hoogstraaten, a leader of the Dominican friars in Cologne. With the Dominicans' support, Pfefferkorn wrote several books. In these books, he tried to show that Jewish religious writings were against Christian beliefs.

His First Books

In his book Der Judenspiegel (published in Cologne, 1507), Pfefferkorn made several demands. He wanted Jewish people to stop lending money for interest, which the Church called usury. He also wanted them to work for a living and attend Christian sermons. Most importantly, he wanted them to get rid of the books of the Talmud.

However, in another book called Warnungsspiegel, he spoke against harming Jewish people. He said that persecuting them would make it harder for them to convert to Christianity. He even defended them against false claims that they murdered Christian children for religious reasons. He claimed to be a friend to Jewish people and said he wanted them to become Christian for their own good. He believed that if they attended Christian sermons and got rid of the Talmud, they would convert.

Changing Views and Stronger Demands

Pfefferkorn faced strong opposition from Jewish communities because of his writings. This made him even more aggressive in his later books. In Wie die blinden Jüden ihr Ostern halten (1508), Judenbeicht (1508), and Judenfeind (1509), he attacked Jewish people fiercely.

In his third book, Judenfeind, he changed his earlier views. He claimed that every Jewish person thought it was good to kill or mock a Christian. Because of this, he said it was a duty for all true Christians to expel Jewish people from Christian lands. He even suggested that people should not obey laws that prevented this. He wrote that people should ask rulers to take all Jewish books except the Hebrew Bible and burn them. He also said that Jewish children should be taken from their parents and raised as Catholics. He concluded by saying that harming Jewish people was God's will, and helping them would lead to damnation.

Efforts to Destroy Hebrew Books

Pfefferkorn was convinced that Jewish books were the main reason Jewish people did not convert. He wanted these books to be seized and destroyed. He got support from several Dominican groups and, through Kunigunde of Austria, the sister of Emperor Maximilian.

On August 19, 1509, Emperor Maximilian ordered Jewish people to hand over all books that were against Christianity. This meant any Hebrew book except the Hebrew Bible could be destroyed. Pfefferkorn began taking books in cities like Frankfurt and Cologne.

The Emperor's Commission

Jewish communities asked the emperor to create a group to look into Pfefferkorn's claims. On November 10, 1509, the emperor put Uriel von Gemmingen, the Archbishop of Mainz, in charge of this matter. Uriel von Gemmingen was told to get opinions from several universities and scholars, including Jacob van Hoogstraaten and Johann Reuchlin.

Pfefferkorn wrote another book, In Lob und Eer dem allerdurchleuchtigsten grossmechtigsten Fürsten und Herrn Maximilian (1510), to gain more favor with the emperor. In April, he continued his work of seizing books in Frankfurt.

Decisions and Reversal

In October 1510, Van Hoogstraaten and the Universities of Mainz and Cologne agreed with Pfefferkorn. They said Jewish books should be destroyed. However, Johann Reuchlin disagreed. He said that only books clearly offensive, like the Nizachon and Toldoth Jeschu, should be destroyed.

The emperor received all the opinions. On May 23, 1510, Emperor Maximilian stopped his order from November 1509. The Jewish books were returned to their owners on June 6.

The Battle of Pamphlets

The disagreement between Pfefferkorn and Reuchlin turned into a public battle of books and pamphlets. This fight showed the larger conflict between the Dominicans and the humanists.

When Pfefferkorn learned of Reuchlin's opinion, he was very angry. He wrote Handspiegel (1511), attacking Reuchlin harshly. Reuchlin complained to the emperor and replied with his own book, Augenspiegel. Pfefferkorn then published Brandspiegel. In June 1513, the emperor ordered both sides to stop publishing.

However, Pfefferkorn did not stop. In 1514, he published Sturmglock, attacking both Jewish people and Reuchlin again. Other young humanists who supported Reuchlin also wrote against Pfefferkorn in a book called Epistolæ obscurorum virorum. Pfefferkorn responded with Beschirmung (1516) and Streitbüchlein (1517).

In 1520, Pope Leo X ruled against Reuchlin, saying his book Augenspiegel was wrong. Pfefferkorn saw this as a victory and wrote Ein mitleidliche Klag (1521). The historian Diarmaid MacCulloch notes that Erasmus was also against Pfefferkorn, partly because he was a convert and not fully trusted by some.

Pfefferkorn's Works

- Der Judenspiegel (The Jewish Mirror), 1507

- Der Warnungsspiegel (The Mirror of Warning), year unknown

- Die Judenbeicht (The Jewish Confession), 1508

- Das Osterbuch (The Easter Book), 1509

- Der Judenfeind (The Enemy of the Jews), 1509

- In Lob und Eer dem Kaiser Maximilian (In Praise and Honor of Emperor Maximilian), 1510

- Handspiegel (Hand Mirror), 1511

- Der Brandspiegel (The Burning Mirror), 1513

- Die Sturmglocke (The Storm Bell), 1514

- Streitbüchlein Wider Reuchlin und Seine Jünger (Book of Disputes Against Reuchlin and His Followers), 1516

- Eine Mitleidige Clag Gegen den Ungläubigen Reuchlin (A Pitiful Complaint Against the Unbelieving Reuchlin), 1521

See also

- Anton Margaritha

- Johann Eisenmenger

- Martin Luther

- Samuel Friedrich Brenz

- Nicholas Donin

- Jacob Brafman

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |