Frederick III, Elector of Saxony facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Frederick III |

|

|---|---|

|

|

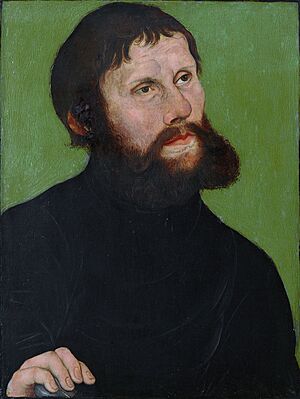

Portrait by Lucas Cranach the Elder

|

|

| Elector of Saxony | |

| Reign | 26 August 1486 – 5 May 1525 |

| Predecessor | Ernest |

| Successor | John |

| Born | 17 January 1463 Torgau, Electorate of Saxony, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 5 May 1525 (aged 62) Castle Lochau near Annaburg, Electorate of Saxony, Holy Roman Empire |

| Burial | Schlosskirche, Wittenberg |

| House | House of Wettin |

| Father | Ernest, Elector of Saxony |

| Mother | Elisabeth of Bavaria |

| Religion |

|

| Signature |  |

Frederick III (born January 17, 1463 – died May 5, 1525) was also known as Frederick the Wise. He was a powerful ruler called the Prince-Elector of Saxony from 1486 to 1525. He is best remembered for protecting Martin Luther, a key figure in the Protestant Reformation. Frederick was the son of Ernest, Elector of Saxony and Elisabeth of Bavaria.

Frederick was one of the earliest and strongest supporters of Martin Luther. He successfully protected Luther from the Holy Roman Emperor, the Pope, and other powerful people who wanted to harm him. Frederick believed that all his subjects deserved a fair trial. This right was guaranteed by the laws of the Holy Roman Empire.

Even though he protected Luther, Frederick is thought to have remained a Roman Catholic for most of his life. However, he slowly started to agree with some of the new ideas of the Reformation. Some people believe he might have changed his faith just before he died.

Many Protestants see him as an important Christian ruler. He is honored in the Calendar of Saints of the American Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod every May 5th.

Contents

Frederick III's Life and Rule

Frederick was born in Torgau. He became the Elector of Saxony in 1486 after his father passed away. In 1502, he started the University of Wittenberg. Later, important religious thinkers like Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon taught there.

Frederick was one of the German princes who pushed for changes from Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. In 1500, he became the head of a new governing council called the Reichsregiment. His official painter from 1504 was the famous artist Lucas Cranach the Elder.

In 1519, Pope Leo X wanted Frederick to become the Holy Roman Emperor. The Pope even gave him a special award called the Golden Rose to convince him. However, Frederick helped Charles V get elected instead. He agreed to support Charles if Charles paid back an old debt to Saxony.

Frederick had a huge collection of relics in his Castle Church. In 1518, he had over 17,000 items. These included a thumb from Saint Anne, a twig from Moses' burning bush, and even milk from the Virgin Mary. People believed that by honoring these relics, they could reduce their time in purgatory. This was part of the belief in indulgences at the time. Some thought that if you honored all his relics, you could avoid millions of years in purgatory! By 1520, his collection grew to over 19,000 pieces.

The Elector's Dream and Luther's Actions

Around October 30, 1517, Frederick had a very important dream. It seemed to predict the start of the Reformation.

In his dream, it was almost All Saints' Day. Frederick was thinking about the festival and praying. He fell asleep and dreamed that a monk, like Paul the Apostle, came to him. All the saints were with the monk, showing he was sent by God. The monk asked to write something on the church door in Wittenberg.

The monk started writing with a pen so long and bright that it reached Rome. It poked a lion there and shook the Pope's special crown. Everyone tried to help the Pope, and Frederick himself tried to support the crown. He woke up scared and annoyed with the monk.

He fell asleep again, and the dream continued. The lion roared, and Rome was in an uproar. The Pope demanded that the monk be stopped, especially by Frederick, since the monk lived in his lands.

Frederick woke up again, prayed for the Pope, and then fell asleep once more. The dream continued: many princes came to Rome, trying to break the mysterious pen. But the more they tried, the stronger it became! The monk said he got the pen from an old teacher. It belonged to a "Bohemian goose" (John Huss, whose name means 'goose' in Czech). This goose had spoken the truth 100 years before. The pen was strong because no one could take its power away. Suddenly, Frederick heard a cry, and many new pens came out of the monk's long pen!

All Saints' Day was a big event in Wittenberg. The valuable relics from the castle church were shown to people. If you visited the church and made confession, you could get a full forgiveness of sins. So, many people came to Wittenberg on this day.

On October 31, the day before the festival, the monk Martin Luther bravely went to the church. He nailed ninety-five statements against the idea of indulgences to the door. He was alone, and his friends didn't know his plan. He said he was ready to discuss his ideas the next day at the university.

Luther's statements quickly got everyone's attention. They were read and shared everywhere. There was great excitement in the university and the city.

These statements strongly challenged the idea of indulgences. Luther argued that the Pope or any other person could not truly forgive sins or remove their punishment. He said the whole system was a trick to get money by using people's superstitions. He also showed that the Gospel of Christ was the Church's greatest treasure. He taught that God's grace was freely given to all who sought it through repentance and faith.

Frederick's Protection of Martin Luther

Martin Luther was an Augustinian friar (a type of monk). He became a priest in 1507. In 1508, he started teaching theology (the study of religious faith) at the University of Wittenberg. This university was in the Electorate of Saxony, which was Frederick III's territory. So, Luther was one of Frederick's subjects.

Luther earned two bachelor's degrees and then his Doctor of Theology in 1512. He became a professor of theology at Wittenberg. In 1515, he was put in charge of eleven monasteries in Saxony and Thuringia.

From 1510 to 1520, Luther taught about parts of the Bible. As he studied, he began to see terms like penance (punishment for sin) and righteousness (being right with God) differently from the Catholic Church. He became convinced that the Church had lost sight of some main Christian truths. For Luther, the most important idea was justification. This means God declaring a sinner righteous only through faith and God's grace. He taught that salvation is a gift from God, received only by faith in Jesus.

Luther eventually disagreed with several teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church, especially about indulgences. He first tried to discuss these differences peacefully.

In 1516, a friar named Johann Tetzel was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church. He was selling indulgences to raise money to rebuild St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

On October 31, 1517, Luther wrote to his bishop, Albrecht von Brandenburg. He protested against the sale of indulgences and included a copy of his "Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences," now known as the Ninety-five Theses.

In 1520, Pope Leo X demanded that Luther take back all his writings. When Luther refused, the Pope excommunicated him (kicked him out of the Church) in January 1521.

To ensure Luther received a fair hearing, Elector Frederick arranged for him to speak before the Diet of Worms in 1521. After Holy Roman Emperor Charles V declared Luther an outlaw, Frederick made sure Saxony was exempt from this order.

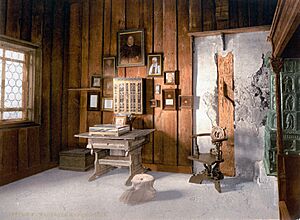

Frederick then protected Luther from the Pope. He faked an attack on Luther's way back to Wittenberg. Masked horsemen pretending to be robbers took Luther and hid him for several years at Wartburg Castle.

Luther's disappearance was planned by Frederick III. Luther was taken to the safety of Wartburg Castle in Eisenach. There, he lived disguised as "Junker Jörg."

While at Wartburg, Luther translated the New Testament from Greek into German. He also wrote many important religious papers.

In the summer of 1521, Luther started to challenge more central Church practices. He wrote that the Mass was not a sacrifice but a gift to be received with thanks. He also said that confession did not have to be forced. He encouraged private confession. In November, he wrote that monks and nuns could break their vows without sin. He believed vows were a wrong way to try to earn salvation.

Frederick's Later Years and Wittenberg Events

Even though Frederick actively protected Luther, they didn't have much personal contact. Frederick's treasurer, Degenhart Pfaffinger, spoke to Luther on Frederick's behalf. Pfaffinger had supported Frederick since they went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land together.

While Luther was hidden at Wartburg Castle, big changes were happening in Wittenberg. Luther was kept informed. Andreas Karlstadt, with support from Gabriel Zwilling, started a very radical reform program in June 1521. This went further than Luther had planned. These reforms caused problems, including monks rebelling and statues in churches being destroyed.

After secretly visiting Wittenberg in December 1521, Luther wrote a warning against rebellion.

Wittenberg became even more chaotic after Christmas. A group of religious fanatics, called the Zwickau prophets, arrived. They preached extreme ideas like everyone being equal, adult baptism, and Christ returning soon. When the town council asked Luther to come back, he felt it was his duty.

Luther secretly returned to Wittenberg on March 6, 1522. He wrote to Frederick: "While I was away, Satan entered my flock and caused damage that I can only fix by being there in person." For eight days in Lent, starting March 9, Luther preached eight sermons. These became known as the "Invocavit Sermons." In them, he stressed the importance of Christian values like love, patience, and freedom. He told the citizens to trust God's word, not violence, to bring about change.

Luther's return had an immediate effect. After his sixth sermon, a Wittenberg lawyer wrote to Frederick: "Oh, what joy Dr. Martin's return has brought us! His words are bringing misguided people back to the truth every day."

Luther then worked with the authorities to bring back public order. He started to act as a more careful force within the Reformation.

Even after his success in Wittenberg and sending away the Zwickau prophets, Luther still had to fight. He fought against the Catholic Church and also against radical reformers who caused social unrest.

Frederick's Personal Faith

Frederick III was a Roman Catholic his whole life. However, he might have become a Lutheran on his deathbed in 1525. This depends on how you view his receiving of a Protestant communion.

Frederick leaned towards Lutheranism in his later years. He made sure Martin Luther was safe. He didn't want Luther to suffer the same fate as Jan Huss and other early reformers. Huss was tried for heresy and excommunicated by the Pope.

It's important to understand what "converting" to Lutheranism meant back then. When Frederick died, the Reformation had only just begun. It was only eight years after Luther published his Ninety-five Theses, which is seen as the start of the movement. Many important works, like Luther's catechisms (1529) and the German Mass (1526), were not yet written. So, Protestant teachings were not fully set. It was just starting to be seen as its own faith, not just a correction or a heresy within Roman Catholicism.

Death and Succession

Frederick died unmarried in 1525 at the age of 62. He passed away at Lochau, a hunting castle near Annaburg. He was buried in the Castle Church at Wittenberg. His grave tomb was sculpted by Peter Vischer the Younger.

Since he had no children, his brother John the Steadfast became the new Prince-Elector of Saxony. John was already a Lutheran before he became elector. He continued Frederick's support for the Reformation. In 1527, John made the Lutheran church the official state church in Saxony.

See also

In Spanish: Federico III de Sajonia para niños

In Spanish: Federico III de Sajonia para niños

- Portrait of Frederick III of Saxony

- Luther (2003 film)

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Frederick III, The Wise". New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third). (1914). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Frederick III, The Wise". New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third). (1914). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

|

Frederick III, Elector of Saxony

Born: 17 January 1463 Died: 5 May 1525 |

||

| Preceded by Ernest |

Elector of Saxony 1486–1525 |

Succeeded by John the Constant |