Cassiodorus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Servant of GodCassiodorus |

|

|---|---|

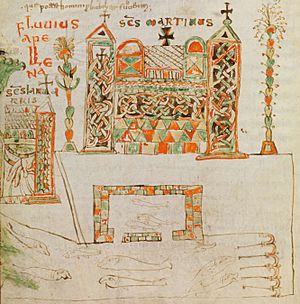

Cassiodorus (Gesta Theodorici: Leiden, University Library, Ms. vul. 46, fol. 2r), dated 1177

|

|

| Layperson and Founder | |

| Born | Flavius Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator c. 490 Squillace, Catanzaro, Italy |

| Died | c. 583 (aged 92–93) Squillace, Catanzaro, Italy |

| Honored in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Major works | Monasteries of Vivarium and Montecastello |

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (born around 485 – died around 585), often called Cassiodorus, was an important Christian leader and writer from ancient Rome. He was a skilled scholar and worked for Theodoric the Great, who was the king of the Ostrogoths. The word Senator was part of his family name, not a job title. Later in his life, Cassiodorus started a monastery called Vivarium. He spent his last thirty years there, working on many important projects.

Contents

Life of Cassiodorus

Cassiodorus was born in a place called Scylletium, near Catanzaro in Calabria, Italy. Some historians think his family might have come from Syria because of his Greek name. His family had many important government officials for several generations. For example, his great-grandfather helped defend southern Italy from Vandal sea-raiders. His grandfather was part of a Roman group that met with Attila the Hun. His father, who had the same name, worked for King Odovacer and later for King Theoderic the Great.

Early Career and Public Service

Cassiodorus started his career when he was about 20 years old. His father, who was a high-ranking official called the Praetorian Prefect, made him his legal advisor. This meant Cassiodorus helped with difficult legal cases. This shows he had a good education in law.

During his career, he held many important jobs. He was a quaestor sacri palatii (a kind of chief legal officer) from about 507 to 511. In 514, he became a consul, which was a very high political position. Later, he was a magister officiorum (head of government departments) for King Theoderic. He also served under Theoderic's young successor, Athalaric.

Cassiodorus was very good at writing. He kept detailed records and letters about public matters. His writing style was considered very skilled, and he was often asked to write important government documents. His highest job was praetorian prefect for Italy. This was like being the prime minister of the Ostrogothic government, a great honor to end his career. Cassiodorus also worked with Pope Agapetus I to create a library in Rome. This library would have Greek and Latin books to support a Christian school.

Challenges and Later Years

Historian James O'Donnell points out that Cassiodorus took a higher position in 523. This happened right after Boethius, another important official, lost his job and was sent to prison. Boethius was later executed. Boethius's father-in-law, Symmachus, also faced the same fate. This was because of growing tension between the old Roman leaders and the Gothic rulers. However, if you read Cassiodorus's official letters, you wouldn't know any of this was happening. He didn't mention the death of Boethius.

King Athalaric died in 534. After this, Cassiodorus's public life was mostly about the Byzantine army trying to take back Italy. It was also about power struggles among the Ostrogoths. Around 537–538, Cassiodorus left Italy and went to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. He stayed there for almost 20 years, focusing on religious studies. This trip helped him learn a lot more about religion.

Cassiodorus spent his life trying to connect different cultures and ideas of his time. He tried to bridge the gap between the East and West, Greek and Latin cultures, and Romans and Goths. He also worked to bring together the orthodox Christian people and their Arian rulers (who had different beliefs). He admired Dionysius Exiguus, who created the Anno Domini calendar system we use today.

When he retired, Cassiodorus founded the monastery of Vivarium. It was on his family's land by the Ionian Sea. After this, his writings became mostly about religion.

Monastery at Vivarium

Cassiodorus's Vivarium "monastery school" had two main parts. One was for coenobitic monks, who lived together in a community. The other was a quiet place for those who wanted to live a more solitary life, like hermits. Both were located near modern-day Squillace. This twin setup allowed both types of monks to live side-by-side.

The Vivarium monastery didn't follow a very strict set of rules, like the Benedictine Order. Instead, Cassiodorus wrote a book called Institutiones to guide the monks' studies. This book focused on texts that were available in the Vivarium library. Cassiodorus wrote the Institutiones over many years, from the 530s to the 550s. He kept updating it until he died.

Cassiodorus wrote the Institutiones as a guide for learning both "divine" (religious) and "secular" (worldly) writings. He had originally planned to start a Christian school in Rome, but that didn't happen. He wrote:

I was moved by divine love to devise for you, with God's help, these introductory books to take the place of a teacher. Through them I believe that both the textual sequence of Holy Scripture and also a compact account of secular letters may, with God's grace, be revealed.

The first part of the Institutiones was about Christian texts. It was meant to be used with his book Expositio Psalmorum (Explanation of the Psalms). The second part of the Institutiones covered subjects that later became known as the Trivium and Quadrivium in medieval liberal arts. These included grammar, rhetoric (the art of speaking and writing well), dialectic (logic), arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy.

Cassiodorus encouraged the study of these worldly subjects. However, he believed they were mainly useful for understanding religious studies, much like St. Augustine thought. So, Cassiodorus's Institutiones aimed to give a complete education for a learned Christian, all in one place.

The library at Vivarium was still active around 630 AD. Monks brought the relics of Saint Agathius from Constantinople there. However, its books were later spread out. For example, a large Bible called the Codex Grandior was bought by an Anglo-Saxon monk named Ceolfrith in 679–80. He took it to Wearmouth Jarrow. This book was then used to copy the Codex Amiatinus, which Ceolfrith later brought back to Italy. Even though Vivarium eventually closed, Cassiodorus's work in collecting classical writings and creating a list of resources was very important for Western Europe in the Late Antique period.

Educational Philosophy

Cassiodorus spent much of his life supporting education for Christians. When his plan for a theology university in Rome was turned down, he had to rethink how people learned. His writings show that he believed reading could change a person. With this idea, he designed the studies at Vivarium. It required a lot of reading and thinking.

By giving a specific order of texts to read, Cassiodorus hoped to help monks become disciplined. The first book in this series was the Psalms. He thought new readers should start with the Psalms because they appeal to emotions. It seems his educational plan was quite successful, as many copies of his Psalmic commentaries were made.

Besides discipline, Cassiodorus also encouraged the study of the liberal arts. He believed these arts were part of the Bible's content. He thought some understanding of them, especially grammar and rhetoric, was needed to fully understand the Bible. These arts were divided into the trivium (rhetoric, idioms, vocabulary, and word origins) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy). He also encouraged the Benedictine monks to study medical texts of that time, including books on herbs and writings by Hippocrates, Dioscorides, and Galen.

Classical Connections

Cassiodorus, along with Boethius, was one of the most important people in the 6th century who worked to save and explore classical literature. He found that the writings of the Greeks and Romans expressed deeper truths that other arts could not. Even though he thought these texts were not as perfect as the Bible, the truths in them fit with Cassiodorus's ideas about education. So, he wasn't afraid to quote Cicero alongside sacred texts. He also recognized the classical idea that being good was part of practicing rhetoric.

His love for classical thought also influenced how he ran Vivarium. Cassiodorus was deeply connected to Christian neoplatonism. This idea suggested that beauty was linked to goodness. This inspired him to improve the artistic look of manuscripts in the monastery. While this had been done before, Cassiodorus encouraged it much more widely.

Classical learning was not meant to replace the Bible in the monastery. It was meant to add to the education already happening. It's also important to know that all Greek and Roman works were carefully checked. This was to make sure that monks were only exposed to texts that fit with the structured learning program.

Lasting Impact

Cassiodorus's influence is significant, even if it's not always obvious. Before he founded Vivarium, copying manuscripts was often a task for less experienced monks or those who were sick. It was done whenever literate monks felt like it. Because of Cassiodorus, monasteries started to copy documents more actively, widely, and regularly. This change in monastic life spread, especially through religious institutions in Germany.

This daily change also gained a higher purpose. Copying wasn't just about discipline; it was about preserving history. During Cassiodorus's lifetime, the study of theology was declining, and classical writings were disappearing. Even as the victorious Ostrogoth armies were in Italy, they continued to damage Christian relics. Cassiodorus's program helped make sure that both classical and Christian literature were saved through the Middle Ages.

Despite his important contributions to monastic order, literature, and education, Cassiodorus's work was not always well-known. After he died, historians like Bede only partly recognized him as a quiet supporter of the Church. Medieval scholars sometimes changed his name, job, home, and even his religion when describing him. Some parts of his works were copied into other texts, suggesting that people read his ideas, but he wasn't generally famous.

His writings that were not part of his educational program need to be looked at carefully. Because he worked under the new Ostrogothic rulers, he sometimes changed how history was told to protect himself. The same could be said about his ideas, which he presented in a way that seemed peaceful and focused on quiet study, keeping him safe from political trouble.

Works

- Laudes (short speeches for public events)

- Chronica (a history of the world up to 519 AD, connecting Gothic and Roman history)

- Gothic History (a long work about the Goths, only parts survive in another book called Getica)

- Variae epistolae (537) (King Theoderic's official government letters)

- Expositio psalmorum (Explanation of the Psalms)

- De anima ("On the Soul") (540)

- Institutiones divinarum et saecularium litterarum (543–555) (a guide for learning religious and worldly writings)

- De artibus ac disciplinis liberalium litterarum ("On the Liberal Arts")

- Codex Grandior (a version of the Bible)

- De orthographia (around 580) (a guide to correct spelling, written when he was 93 years old)

- Historiae Ecclesiasticae Tripartitae Epitome (a church history, co-written with Epiphanius Scholasticus)

See also

In Spanish: Casiodoro para niños

In Spanish: Casiodoro para niños

- Benedict of Nursia

- Boethius

- Quintus Aurelius Memmius Symmachus

- Theodoric the Great

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |