Angelo Emo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Angelo Emo

|

|

|---|---|

Bust of Emo by Pietro Zandomeneghi, 1862–1863

|

|

| Born | 3 January 1731 Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Died | 1 March 1792 (aged 61) La Valletta, Hospitaller Malta |

| Buried |

San Biagio, Venice (since 1817)

|

| Allegiance | Republic of Venice |

| Service/ |

Venetian navy |

| Years of service | 1752–1792 |

| Rank | Capitano Straordinario delle Navi, Provveditore Generale da Mar |

| Battles/wars | Venetian bombardments of the Beylik of Tunis |

Angelo Emo (born January 3, 1731 – died March 1, 1792) was a Venetian noble, a government official, and a great admiral. He is famous for improving the Venetian navy and leading important naval battles. Many people see him as the last great admiral of the Venetian Republic.

Born into an important family, Emo received an excellent education. He started his navy career as a cadet in 1752. He quickly showed his skills and was given command of a large warship just two years later. In 1758, he led three ships to protect a trade convoy returning from London. His ships faced terrible weather and were almost destroyed. Even so, Emo showed great determination and skill, earning praise from everyone.

After returning to Venice in 1759, he took on both naval commands and government jobs. In these roles, he always pushed for modern ideas and reforms. As a naval leader, he guided the Venetian fleet in shows of strength against the Barbary states. He also kept an eye on the Russian fleet during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774.

In 1775, he suggested changes to the navy based on the British Royal Navy. He could not put these ideas into practice until 1782, when he took charge of the Arsenal of Venice, a major shipyard. New building methods were introduced, training and pay for sailors got better, and new warships were built. From 1784 to 1785, Emo led the Venetian fleet in attacks on the ports of Tunis. This was to stop pirate attacks on Venetian ships. He wanted to land troops and capture Tunis, but his requests were turned down. He spent his last years fighting pirates and died on March 1, 1792, after a short illness. His body was brought back to Venice, where he received a hero's funeral. A special monument was made in his honor by the sculptor Antonio Canova.

Contents

Angelo Emo's Life Story

Early Years and Education

Angelo Emo was born in Venice in January 1731. While January 3 is often given as his birthday, some sources mention the 4th, 5th, or even the 23rd. He was born at the Palazzo Emo, in the San Simeone Piccolo area. His family was a well-known noble family in Venice, tracing its roots back to the 10th century. However, they did not play a major role in Venetian politics until the 18th century.

Angelo Emo's father, Giovanni di Gabriele, became a Procurator of Saint Mark. This was the highest honor for a Venetian citizen, second only to the Doge of Venice. His mother was Lucia Lombardo. Angelo was the third child of his father, with an older sister, Fiordaliso, and an older brother, Alvise, from his father's first marriage. He also had a younger sister, Cecilia. His cousin, Giacomo Nani, born in 1725, also became a famous admiral a few years before Emo.

Angelo Emo was not very tall and had a slim build. His family initially wanted him to become a priest. So, at age twelve, he went to a Jesuit school in Brescia. He returned to Venice in 1748, where his father chose famous scholars to teach him. Young Emo was very good at philosophy but less so in other subjects. During his studies, he was often asked to join the church, but he always refused. He loved studying Venetian history and wanted to achieve military greatness like the heroes he read about. He also admired the ancient Roman historian Tacitus.

By law, young noblemen in Venice had to serve four years in the Venetian navy. Emo joined the navy in 1751 or 1752 as a gentleman cadet. In 1752, he went on his first sea trip, escorting a Venetian trade convoy to Smyrna. His ship, the large frigate San Vincenzo, caught fire and sank in Corfu on May 11. Emo learned quickly about naval matters, and his first commander saw his great potential as an officer. He rose through the ranks fast. In January 1755, he was promoted to captain of a first-rate ship, the 74-gun ship of the line Sant'Ignazio.

During the 18th century, Venice's sea trade, once very powerful, was shrinking. Rich families preferred to invest in land rather than risk their money at sea. New trade centers like Livorno and Trieste took business away from Venice. Pirate attacks were a constant danger, and merchants from Genoa, the Netherlands, and England controlled the routes to the Atlantic. Pirates from the Ottoman-linked areas of Algiers and Tunis, and smaller pirate towns like Bar and Ulcinj, were also a threat. The main job of the Venetian fleet, based in Corfu, was to protect Venetian ships from these attacks.

The Venetian navy had also become weaker. After peace treaties in 1718, 1733, and 1736, the risk of war with the Ottoman Empire decreased. Despite occasional scares, the navy was cut back as Venice focused on staying neutral. Ships being built at the Arsenal of Venice were left unfinished for decades. The Arsenal itself became neglected, with old methods and problems. This situation even threatened Venice's control over the Adriatic Sea. By 1756, the Venetian fleet at Corfu had only seven ships. However, twenty more ships were stored in the Arsenal, almost ready. An increase in pirate attacks forced Venice to put these ships into service. During these years, Emo became known for protecting trade convoys to Smyrna. He fought off pirates, especially those from Ulcinj, and even recaptured a Venetian merchant ship from them. He then commanded the 58-gun Speranza.

In 1758, Emo took command of the 74-gun San Carlo Borromeo, the newest ship of its kind. Emo tested a new mast design on this ship, inspired by English models. These masts were made from several pieces of wood instead of one tree trunk. Emo showed how well the new masts worked while taking the new admiral, Francesco Grimani, to Corfu. Despite strong winds, Emo ordered all sails set to test the masts. Grimani eventually told him to reduce sail.

Journey to Portugal

In 1758, Emo was given a mission to lead an expedition to Lisbon, Portugal. His task was to wait for six Venetian merchant ships coming from London and protect them from expected pirate attacks. He was given a group of three ships: the San Carlo Borromeo, the 58-gun San Vincenzo Ferrer, and the 28-gun frigate Costanza. All were fairly new ships. Emo's ships left Corfu on September 27, 1758. Three days later, they reached Malta, where they gathered information about pirates. They also tried, without success, to find a skilled pilot who knew the Atlantic waters up to Lisbon.

Emo sailed west in mid-October. Strong winds delayed the journey near Malaga. Finally, the Venetians crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and headed for Lisbon. Unfortunately, Emo's pilot mistook Cape da Roca for Cape Espichel, almost causing the San Carlo to crash into the shore. Emo realized the mistake and tried to change course, but the strong wind made it difficult. Emo had to reduce sail, and three sets of sails were torn apart by the wind. The San Carlo managed to pass the Berlengas islands, but the other two ships were left behind. After two days of fighting the wind, Emo anchored at the mouth of the Mondego River. Almost immediately, the ship lost its steering part, called a tiller. A new tiller was put in with great effort, but it broke during the night. Soon after, the entire rudder broke. Some of his officers panicked and suggested beaching the ship, but Emo managed to keep everyone calm. He contacted the shore, and with help from the British vice-consul, arranged for Portuguese ships to tow the San Carlo to Lisbon.

Near Cape da Roca, a strong easterly wind forced the towing ships to give up. The San Carlo was left to drift without a rudder for several days. The crew tried to build a temporary rudder. The Costanza, also badly damaged and leaking water, was seen, and the two ships stayed in contact for a day before drifting apart again. Water supplies on the San Carlo became low. A temporary rudder was finally installed. This allowed the ship to reach Cape da Roca again, before another strong wind from the south pushed the San Carlo north. The new rudder had to be cut free. Only with great difficulty, by sailing backward, did the crew barely avoid a shipwreck at the Berlengas.

By this time, the crew had shrunk from 590 to about 130 men due to accidents, illness, and tiredness. Although the ship's masts and ropes were damaged, it managed to reach a spot north of its original anchorage. This time, Emo went ashore himself and got help from the local Portuguese governor. It took 17 days to build a new rudder and five more days to install it. The ship's effective crew was down to 70, most of whom were tired and new soldiers. Accidents continued as Emo tested his repaired ship. Finally, he was able to turn south to Lisbon, entering the Tagus River on February 5, 1759. There he found his other two ships: the San Vincenzo had arrived on December 8, and the Costanza on December 22.

In Lisbon, where Emo's struggle had been watched with great interest, he was welcomed by King Joseph I like an ambassador. Taking charge of the Venetian merchant ships from London, he returned home via Genoa and Naples with few problems, reaching Corfu in mid-July 1759. During the journey, the San Carlo lost 250 crew members, the San Vincenzo lost 90, and the Costanza lost four. Another 76 crew members (from an original total of 1236 for the whole group of ships) left the navy. Emo's actions during the voyage showed his great sailing and command skills. He earned praise from the government when he returned to Venice in August. However, some people criticized Emo's decision to continue without skilled pilots. Officially, the near-disaster was blamed on a bad design of the San Carlo. The ship was repaired, but it sank with all hands during another storm in 1768.

Government Jobs and High Command

Following Venetian tradition, a military job was followed by a civilian one. So, in 1760, Emo became the health commissioner. Emo accepted this job, but he was not happy about it. For a naval officer, this job was seen as a step down. However, Emo did his duties with great effort. After his year-long term, he was elected as the water commissioner in 1761–62. In this role, he ordered a map of the Venetian Lagoon, which was finished in six months. This map was so accurate that it was used until the 19th century.

In 1763, Emo finally returned to the navy. He was elected to the higher rank of rear admiral of the sailing fleet. He was put in charge of fighting pirates in the Adriatic Sea. His election was not easy. In the first vote, the job went to Alvise da Riva. Only when da Riva resigned, finding the sea conditions too difficult, was Emo elected. The reasons for the first rejection are not clear. Da Riva might have had more political support, as a naval command could lead to higher government positions. Also, Emo's cousin, Giacomo Nani, was already the full admiral of the sailing fleet. There might have been concerns about one family having too much control over the navy. Instead of sailing directly to Corfu, Emo traveled by land through Italy. He visited Florence, Rome, and Naples, where he met King Charles VII. He then boarded a ship at Otranto. During the next sixteen months, Emo focused on protecting merchant ships from pirate attacks. His main success was getting back two Venetian ships and all their cargo from the Dulcignoti pirates. This achievement was celebrated on a special coin minted that year (1765). In the same year, Emo was promoted to vice admiral of the sailing fleet.

Unlike the constant fight against pirates in the Adriatic, Venice chose a different approach against the Barbary states in the 1760s. Agreements were made with Algiers and Tunis in 1763, Tripoli in 1764, and Morocco in 1765. These rulers agreed to stop pirate attacks on Venetian ships in the Adriatic and near the Venetian Ionian Islands. In return, Venice paid a large annual tribute. However, the Barbary rulers did not always follow these agreements. In 1766, Emo's cousin, Giacomo Nani, had to lead a naval show of force near Tripoli to ensure a captured Venetian ship was released. The next year, it was Emo's turn to do a similar operation against Algiers. Its ruler tried to demand more money and captured Venetian ships and their crews. Emo sailed to Algiers with his frigate Ercole, joined by San Michele Archangele and Costanza. He threatened to bombard the city. The ruler of Algiers released the ships and crews, paid for damages, and renewed the treaty with Venice on the old terms. Emo then went to Marseilles, where he bought two fast ships called xebecs for the Venetian fleet. Venice honored Emo with an award, the Order of the Golden Stole. Emo's brother, Alvise, was sent to Marseilles to give him the award's symbols. On June 12, 1768, Emo was promoted to full admiral.

Russo-Turkish War

When the Russian fleet arrived in the Mediterranean in 1770 during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, Emo led a Venetian squadron to sail in the Aegean Sea. His job was to watch the Russians and protect Venetian and French people and businesses in the area. Emo did his job very well, constantly sending updates on Russian operations and smart reports on their war plans. During this conflict, pirates from Ulcinj, who claimed to be working for the Ottoman Sultan, attacked the Venetian Ionian Islands. Emo chased them near Kythira and got back two captured ships.

Emo's fleet suffered heavy losses in a storm near Cape Matapan on December 19, 1771. Half of his ships, the 74-gun Corriera and the 28-gun frigate Tolleranza, sank near Elos, with almost everyone on board lost. Emo's own ship, the 74-gun Ercole, only survived by cutting down its masts. Emo himself was swept into the sea during this action but was rescued by his crew with difficulty. Upset by what he saw as a personal failure, Emo offered to use his own money to make up for the losses.

Emo's naval command ended in 1772. He joined the Venetian Senate and also traveled abroad. He visited the courts of Frederick II of Prussia and Maria Theresa of Austria. He was elected several times as a censor, working to bring back the making of Murano glass.

In March 1775, Emo was named to a seven-member group to study reforms for the Venetian navy. The navy was in a very bad state, and people had debated reforms for decades, but nothing had been done. Emo wrote the group's report, which suggested reforms based on the British Royal Navy. However, even though the group included some powerful senators, their ideas were not put into action.

From 1776 to 1778, Emo again served as the water commissioner. He was responsible for several maintenance projects around the Lagoon, on the Brenta River, the Terraglio road, and the Cava canal.

Show of Force off Tripoli

Emo received another naval command on July 18, 1778. He was elected admiral, with the heavy frigate Sirena as his main ship. His mission was to confront the ruler of Tripolitania, who was trying to search Venetian ships beyond what was allowed by treaty. Emo led his fleet in a show of force in front of Tripoli. This led the ruler to sign a new peace agreement with Venice. Emo's appointment was renewed for the next year, but he did not need to sail.

In 1779, as a trade commissioner, Emo supported reforms like lowering taxes on silk. He also pushed for opening new shops in Šibenik and moving the Venetian consulate in Egypt from Cairo to the port city of Alexandria. In 1780, he was a commissioner for uncultivated lands. He made plans for draining the marshlands around Verona, a project started by Zaccaria Betti. However, these plans were not carried out due to a lack of money.

During the visit of Grand Duke Paul (who would later become Tsar Paul I of Russia) to Venice in January 1782, Emo personally taught Paul about the Venetian navy. When Venice decided to send a permanent ambassador to Saint Petersburg shortly after, Emo's name was at the top of the list. However, he managed to avoid this expensive and unwanted job by saying he was ill. In 1783, as a special commissioner, Emo led talks with the Habsburg ambassador Philipp von Cobenzl about freedom of navigation in Istria and Dalmatia.

From 1782 to 1784, Emo served as one of three special inspectors for the Venetian Arsenal. This appointment came from the reform-minded senator Francesco Pesaro. Their job was to fix the ongoing problems at this very important shipyard. His fellow directors were Giovanni Zusto and Nicolò Erizzo. Emo brought in new ship designs from England and France. He introduced copper sheathing for warships, which made them faster and cheaper to maintain. He also improved how ropes and rigging were made. He increased the pay for non-noble officers and started theoretical training for naval cadets. He also created a public welfare plan for sick and old sailors. Taking advantage of the sudden sinking of the ship Fenice in 1783, the inspectors were able to break the control that old-fashioned chief shipwrights had over naval construction. They replaced them with a group of naval architects. Using his position as a senator and his connections in the government, Emo secured money to build new warships. Fifteen were started after his time in charge and before the Republic ended in 1797.

On March 6, 1784, Emo was elected commander-in-chief of a naval expedition against the Beylik of Tunis. The new Bey, Hammuda ibn Ali, was warlike and had a dispute with Venice that quickly turned into war. A Venetian ship carrying goods from Tunis was burned in Malta because it was infected with the plague. The Bey demanded a huge payment. When the Venetian admiral Andrea Querini tried to negotiate, he was attacked by a crowd organized by the Bey. On June 21, Emo sailed from Venice on a slow journey to Corfu, where more ships joined him. His fleet included a few large warships, including Emo's main ship, the 64-gun Fama, some xebecs, two bomb vessels, and a galiot. The fleet sailed for Tunis on August 12.

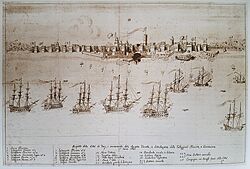

Emo's ships anchored at Cape Carthage, five miles from the city of Tunis, on September 1. The Tunisian fleet, which focused on piracy against merchant ships, did not sail out to fight the Venetians. The Venetians were able to sneak into the harbor of La Goulette during the night of September 3-4 and recapture a Neapolitan merchant ship that pirates had just taken. After getting water and supplies in Sardinia, Emo sailed for Sousse. He bombarded Sousse on October 5-7 and 12, before autumn storms forced him to spend the winter in Trapani, Sicily, and Malta.

Emo returned to the Tunisian coast in April 1785, anchoring at La Goulette. Talks with the Bey of Tunis failed, and Emo sailed back to Malta and Sicily. The Venetian fleet again bombarded Sousse on and off (July 21-27 and July 31 – August 4) due to bad weather, but with little success. Sfax was next (August 15-17), before the fleet went back to Trapani. After getting more ships from Venice, which increased his fleet to five large warships, one light frigate, two xebecs, one galiot, and two bomb-vessels, Emo returned to La Goulette. Here, Emo used floating batteries that he invented. These were large floats made of empty barrels, protected with wet sandbags, and armed with 40-pound guns and mortars. Along with the bomb-vessels, these gave the Venetians the ability to hit targets behind the sea walls during the nights of October 3, 5, and 10. Since the Bey remained stubborn, Emo took apart his rafts and returned to Trapani.

As the Bey continued to insist on his demands, Emo returned to the Tunisian coast in early 1786. He attacked Sfax (on March 6, 18, and 22, April 30, and May 4). The Tunisians had prepared for his arrival, repairing their walls and installing heavy guns. This led to intense artillery duels between the city and the fleet. Emo had also seen how effective his floating batteries were and had built more of them, with even heavier mortars. In nightly operations, they were brought close to the sea walls and bombarded the city's inside with such strong effect that the people of Sfax begged the Bey to restart talks, but it did little good. The Venetian fleet went back to Malta. There, Emo received news that he had been elected Procurator of Saint Mark on May 28. This event was celebrated for three days and nights. With the Bey still refusing to negotiate, Emo attacked Bizerte from July 30 to August 10. Then, from September 26 to October 6, he attacked Sousse, which was now almost completely destroyed.

These operations caused great damage and many casualties in these cities. They also kept the Tunisian pirate fleet stuck in its harbors. Emo became famous throughout Europe, where stories of his firework-like night bombardments captured people's imaginations. However, these attacks failed to achieve their main goal: to force the Bey of Tunis to negotiate. Venice, like other European naval powers, preferred to make agreements with the pirates, including annual payments, rather than fight long and much more expensive military campaigns to completely stop the pirate threat. Thus, Emo's requests for a 10,000-man army to attack and capture Tunis were rejected by the Venetian Senate.

Final Years and Death

In early 1787, the Senate called Emo back with most of his fleet. Only a small group of ships under Admiral Tommaso Condulmer was left to patrol the Tunisian coast. Emo's recall was likely connected to the upcoming war between Russia and the Ottomans. Some alarm was caused by an Ottoman fleet that appeared off the coasts of Albania in August. But Emo, who watched its movements with a much stronger force, was not worried. In the end, the Ottoman fleet's mission was only to impress the rebellious ruler of Scutari. After doing that, it returned to its base in early 1788. Until 1791, Emo spent his time fighting pirates off the western coasts of Greece. He made one trip into the Aegean Sea in 1790 that brought him to Paros. For his efforts against the Tunisian pirates, the nobles of Zakynthos gave him a golden sword and a medal.

In late 1790, the Senate named Emo commander-in-chief of the fleet. However, they did not trust him to lead the fleet against the Tunisian coast. With the French Revolution happening in Europe, the Senate did not want to get involved in a long conflict. They preferred peace. The Senate feared that Emo's aggressive nature would hinder these efforts. Instead, they put Condulmer, who was promoted to admiral, in charge of the naval blockade and peace talks. In 1791, the Venetian government decided on a final show of force. They brought together Emo's fleet and Condulmer's squadron. The combined fleet demonstrated off the Tunisian coast from late August until returning to Malta in December. Emo was hospitalized after a lung infection and died in La Valetta, Malta, on March 1, 1792.

Celebrated as a great naval hero, his body was preserved and carried to Venice on board his flagship, the Fama. The sculptor Antonio Canova was asked to build a monument to Emo. Finished in 1794, it is in the second armory of the Venetian Arsenal. Canova was honored by Venice with a medal for this monument, the last such medal given by the Republic before it ended. Emo's funeral took place at St Mark's on April 17, and he was buried at the church of Santa Maria dei Servi. A monument was built over his tomb by Canova's teacher, Giovanni Ferrari. It was first at Santa Maria dei Servi, then moved to San Martino, and finally, from 1817, to San Biagio.

Legacy

After his older brother, Alvise Emo, died in 1790, Angelo Emo's death also meant the end of his branch of the Emo family.

Even at the time of Emo's death, his loss was seen as a major blow and a sign of Venice's decline. Emo's reputation grew even more with historians in the 19th century. They liked to romanticize the final years of the Republic. Girolamo Dandolo called him "the last roar issued by the Lion of St. Mark on the sea." For Samuele Romanin, Emo might have been able to "shake [the Republic] from its disastrous abandonment" and "inspire in her the strength and energy" that she badly needed in her final years. Romanin believed Emo was the last of the great military commanders of the Venetian navy and of the Republic itself. He said that the Republic "may indeed be said to have herself descended with him into the sepulchre." After him, the Venetian navy would no longer be called upon to fight.

Two submarines of the Royal Italian Navy were named after him.

Images for kids

See Also

- Venetian navy

- Republic of Venice

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |