Roman people facts for kids

| Latin: Rōmānī Ancient Greek: Ῥωμαῖοι, Rhōmaîoi |

|

|---|---|

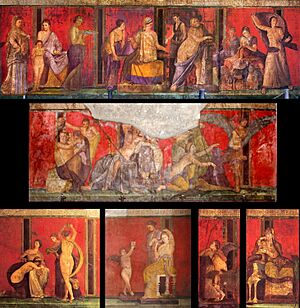

1st century AD wall painting from Pompeii depicting a multigenerational banquet

|

|

| Languages | |

|

|

| Religion | |

|

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ancient Italic peoples, ancient Mediterranean peoples, modern Romance peoples and modern Greeks |

The Roman people were the citizens of Ancient Rome during its long history, from the Roman Kingdom to the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. What it meant to be Roman changed a lot over time as Rome grew and shrank. At first, only the Latins living in Rome itself were considered Roman citizens. But by the 1st century BC, this citizenship was given to other Italic peoples in Italy. Later, in late antiquity, almost everyone living freely in the Roman Empire could become a citizen.

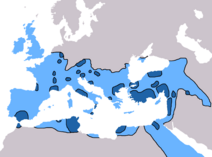

At their strongest, the Romans ruled huge parts of Europe, the Near East, and North Africa. They gained these lands through wars and conquests during the Republic and Empire. Being "Roman" was mainly about citizenship, but it also became a cultural identity, a nationality, or even a mix of different ethnicities. This mix included many different groups from across the empire.

More people became Roman citizens through new laws, population growth, and new settlements. A big change happened in AD 212 when Emperor Caracalla issued the Antonine Constitution. This law gave citizenship to all free people in the empire. Being Roman helped people feel connected and different from non-Romans, like barbarian invaders. Roman culture was not all the same everywhere. It had common ideas, but it also welcomed traditions from other cultures, especially Greece.

When the Western Roman Empire fell in the 5th century, Rome's political power in Western Europe ended. But being Roman still mattered for a while. The Eastern Roman Empire, also called the Byzantine Empire, tried to get back control of the west but failed. New Germanic kingdoms took over, and Roman identity slowly disappeared in the west by the 8th and 9th centuries. In the Greek-speaking east, where the empire still ruled, Roman identity lasted until the Byzantine Empire fell in 1453 and even longer.

While Roman identity faded in most places, it stayed strong in some areas. In Italy, people from Rome are still called "Romans" (Romani) today. In the Eastern Roman Empire, Greeks called themselves Romioi or similar names. In Switzerland, names like Romands and Romansh people come from "Roman." Other names, like Romanians, Aromanians, and Istro-Romanians, also come from the Latin word Romani.

Contents

What Did Being Roman Mean?

Understanding "Roman" Identity

Today, the word "Roman" can mean a historical time, a type of culture, a place, or a personal identity. These ideas are connected but not exactly the same. Many historians have their own ideas about what being Roman meant, often called Romanitas. However, this word was rarely used in Ancient Rome itself. Like all identities, being "Roman" was flexible and changed over time.

Since Rome was a huge state that lasted for a very long time, there is no single, simple definition of what it meant to be Roman. Even in ancient times, people had different ideas. Some ancient Romans thought that geography, language, and family background were important for being Roman. Others believed that Roman citizenship, culture, or behavior mattered more.

At the height of the Roman Empire, Roman identity was a shared political identity. It included almost all subjects of the Roman emperors, even with their many different backgrounds. Often, what a person believed and did was more important than their family history. For famous Roman speakers like Cicero, being Roman meant following Roman traditions and serving the Roman state. Cicero himself was a "new man," the first in his family to join the Roman Senate. This meant he didn't have a long line of famous Roman ancestors. But this doesn't mean family history was ignored. Speakers like Cicero often reminded noble families to live up to their ancestors' "greatness."

Rome was very good at including and integrating other peoples, a process called Romanization. This idea came from Rome's founding stories. These myths said that Rome was started as a safe place by Romulus, where different peoples mixed from the very beginning. Cicero and other Roman writers made fun of people like the Athenians, who were proud of their shared family lines. Instead, Romans were proud of their city being a "mongrel nation," meaning it was made up of many different groups. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek historian who lived in Roman times, even said that Romans had welcomed countless immigrants from all over Italy and the world since the city's founding.

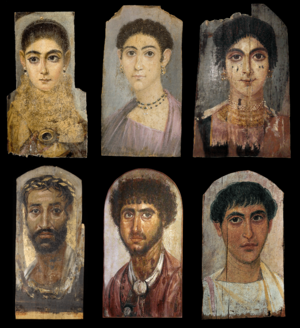

A few Roman writers, like Tacitus and Suetonius, worried about Roman "blood purity" as more citizens came from outside Italy. However, neither writer suggested stopping new citizens from joining. They only thought that freeing slaves (manumissions) and giving citizenship should happen less often. Their worries about blood purity were not like modern ideas of race or ethnicity. They had little to do with skin color or looks. Terms like "Aethiop," which Romans used for black people, had no social meaning. While stereotypes about looks existed, physical traits usually didn't affect social status. People who looked different, like black people, were not kept out of any jobs. There are no records of prejudice against "mixed race" relationships. The main social differences in Ancient Rome were based on class or rank, not physical features. Romans had many slaves, but these slaves came from many different groups. They were not enslaved because of their ethnic background. According to historian Emma Dench, it was "notoriously difficult to detect slaves by their appearance" in Ancient Rome.

Who Were Not Romans?

Ancient Rome is often called a "non-racist society." However, Romans did have strong cultural stereotypes against groups and peoples not part of the Roman world. These were called "barbarians." While views changed over time, most Roman writers in late antiquity felt that "the only good barbarian is a dead barbarian." Throughout history, most Roman emperors put anti-barbarian images on their coins. For example, the emperor or Victoria (the goddess of victory) would be shown stepping on or dragging defeated barbarian enemies.

According to Cicero, people were barbarians not because of their language or family, but because of their customs or lack of good character. Romans thought they were better than foreigners. This wasn't because of perceived biological differences. It was because they believed their way of life was superior. So, "barbarian" was a cultural term, not a biological one. It was possible for a barbarian to become Roman. The Roman state even saw it as its duty to conquer and "civilize" barbarian peoples.

One group of non-Romans who were particularly disliked within the empire were the Jews. Most Romans disliked Jews and Judaism, though opinions varied among the Roman elite. Many, like Tacitus, were hostile to Jews. Others, like Cicero, were simply uninterested. Some didn't see Jews as barbarians at all. The Roman state wasn't completely against Jews. There was a large Jewish population in Rome itself, with at least thirteen synagogues. Roman antisemitism, which led to several wars and persecutions in Judea, was not based on race. Instead, it came from the idea that Jews, unlike other conquered peoples, refused to join the Roman world. Jews followed their own rules and religion, which Romans often disliked or misunderstood. Their refusal to adopt Roman customs, even after being conquered, made Romans suspicious.

Roman History: From Republic to Empire

Early Romans and Their Beginnings

The story of Rome's founding and its first few centuries is full of myths and unclear details. The traditional dates for Rome's founding (753 BC) and the start of the Roman Republic (509 BC) are used today, but they are not certain. The myths about Rome's founding mix several stories. These include the origins of the Latin people, Evander of Pallantium bringing Greek culture to Italy, and a Trojan origin through the hero Aeneas. The actual mythical founder of the city, Romulus, appears many generations into these complex stories. Ancient writers had different ideas about these myths. But most agreed that their civilization was founded by a mix of migrants and people seeking refuge. These origin stories helped explain why Rome later welcomed so many foreigners.

The first Romans were mainly Latin-speaking Italic people, known as the Latins. They were part of the Latin homeland, called Latium. By the 6th century BC, Rome had conquered other Latin settlements and defeated Alba Longa, which had led the Latin people. Rome now held that position.

From the mid-4th century BC, Rome won many wars. By 270 BC, they ruled all of Italy south of the Po river. After conquering Italy, Romans fought powerful enemies like Carthage and the Hellenistic kingdoms in the east. By the mid-2nd century BC, Rome was the clear master of the Mediterranean. By the late 3rd century BC, about a third of the people in Italy south of the Po river were Roman citizens. This meant they had to serve in the army. The rest were allies, often asked to join Roman wars. These allies later became Roman citizens after the Social War, which happened because the Roman government refused to grant them citizenship. In 49 BC, Julius Caesar also gave citizenship to people in Cisalpine Gaul. The number of Romans grew quickly in later centuries as citizenship was extended further.

There were five main ways to become a Roman citizen:

- Serving in the Roman army.

- Holding office in cities with Latin rights.

- Being granted citizenship directly by the government.

- Being part of a community that received citizenship as a "block grant."

- As a slave, being freed by a Roman citizen.

Just as it could be gained, Roman status could also be lost. For example, through corrupt actions or being captured by enemies. However, one could become Roman again after returning from captivity.

Romans in the Early Empire

In the early Roman Empire, people belonged to different legal groups. These included Roman citizens (cives romani), people from the provinces (provinciales), foreigners (peregrini), and free non-citizens like freed slaves. Roman citizens followed Roman law. Provincials followed the laws of their area before Rome took over. Over time, Roman citizenship was given to more and more people. People moved from less privileged groups to more privileged ones. This increased the number of people recognized as Romans. The Roman Empire's ability to include foreigners was key to its success. It was much easier for a foreigner to become Roman than to become a citizen of any other state at that time. Even some emperors, like Claudius (r.41–54), thought this was important. He told the senate when they questioned letting Gauls join:

What else proved fatal to Lacedaemon or Athens, in spite of their power in arms, but their policy of holding the conquered aloof as alien-born? But the sagacity of our own founder Romulus was such that several times he fought and naturalized a people in the course of the same day!

From the Principate (27 BC – AD 284) onwards, barbarians settled and became part of the Roman world. These settlers gained certain legal rights just by being in Roman territory. They became provinciales and could serve as auxilia (auxiliary soldiers). This service then made them eligible to become full Roman citizens (cives Romani). Through this quick process, thousands of former barbarians could become Romans. This tradition of easy integration led to the Antonine Constitution, issued by Emperor Caracalla in 212 AD. This law gave citizenship to all free people in the Empire. Caracalla's grant greatly increased the number of people with the nomen (family name) Aurelius.

By the time of the Antonine Constitution, many people in the provinces already saw themselves as Romans. Over centuries of Roman expansion, many veterans and people seeking opportunities had settled in the provinces. Julius Caesar and Augustus alone settled between 500,000 and a million people from Italy in Rome's provinces. By AD 14, four to seven percent of free people in the empire's provinces were already Roman citizens. Besides colonists, many provincials also became citizens through grants from emperors and other ways.

It's not always clear how much new Roman citizens felt Roman, or how others saw them. For some provincials, their only experience with "Romans" before gaining citizenship was through Rome's tax system or its army. These aspects didn't always create a shared Roman identity. Caracalla's grant changed imperial policy a lot. It's possible that centuries of Romanization had already started a "national" Roman identity before 212 AD. The grant might have just made this process legal. Or, it might have been the key step for a later, widespread Roman identity. According to British lawyer Tony Honoré, the grant "gave many millions, perhaps a majority of the empire's inhabitants […] a new consciousness of being Roman." Local identities likely survived after Caracalla's grant. But identifying as Roman gave people a larger shared identity. This became important when dealing with non-Romans, like barbarian settlers and invaders.

Ancient Romans often linked their identity to things historians do today:

- Rich ancient Latin literature.

- Impressive Roman architecture.

- Common marble statues.

- Many religious sites.

- Roman roads and legal system.

- The strong identity of the Roman army.

These were all cultural ways to show Roman identity. Even with a common Roman identity, Roman culture in classical times was not all the same. It had shared ideas, often based on earlier Hellenistic culture. But Rome's strength was also its flexibility and ability to include traditions from other cultures. For example, the religions of many conquered peoples were adopted. Their gods were mixed with Roman gods. In Egypt, Roman emperors were seen as successors to the pharaohs and shown as such in art. Many cults from the eastern Mediterranean spread to Western Europe under Roman rule.

Romans in Late Antiquity

The city of Rome, once the heart of Roman identity, slowly lost its special status in late antiquity. By the end of the 3rd century, its importance was mostly symbolic. Emperors and rulers began to govern from other cities closer to the empire's borders. Rome's loss of status was also seen in how Romans viewed the city. In the writings of the 4th-century Greek-speaking Roman soldier Ammianus Marcellinus, Rome is described almost like a foreign city. He made negative comments about its corruption. Few Romans in late antiquity fit all parts of traditional Romanness. Many came from distant provinces and practiced religions new to Rome. Many also spoke "barbarian languages" or Greek instead of Latin. Few writings from late antiquity clearly call people "Roman citizens" or "Romans." Before the Antonine Constitution, being Roman was a mark of honor and often highlighted. But after the 3rd century, Roman status was just assumed. This silence doesn't mean Romanness no longer mattered. It meant it was less unique than other identities, like local ones. It only needed to be mentioned if someone had recently become Roman, or if their Roman status was questioned. Romans themselves believed that the populus Romanus, or Roman people, were a "people by constitution." This was different from barbarian peoples, who were gentes, or "peoples by descent" (ethnic groups).

Since being Roman became almost universal in the empire, local identities became more important. In the late Roman Empire, you could identify as a Roman citizen of the empire. Or you could identify as someone from a major region (like Africa or Gaul) or a specific province or city. Romans didn't see these as the same, but there wasn't a big difference between these Roman sub-identities and the gens identities of barbarians. Sometimes, Roman writers described different qualities for citizens from different parts of the empire. For example, Ammianus Marcellinus wrote about differences between 'Gauls' and 'Italians'. In the late Roman army, there were groups named after Roman sub-identities, like 'Celts' and 'Batavians'. There were also groups named after barbarian gentes, like the Franks or Saxons.

The Roman army changed a lot in the 4th century. Some called it "barbarization," meaning many barbarian soldiers were recruited. Even though their barbarian origins were rarely forgotten, the Roman army's large size and focus on skill made it easy for "barbarian" recruits to join and rise through the ranks based on their abilities. It's not clear how much non-Roman influence there truly was. It's possible many barbarians became part of the regular Roman military. It's also possible there was a "barbarian chic" in the army, like the 19th-century French Zouaves (French military units who adopted native clothing). The rise of non-Roman customs in the military might not have been from more barbarian recruits. It could have been from Roman military units along the borders forming their own unique identities. In the late empire, Romans not in the military sometimes used "barbarian" for Roman soldiers on the border, because of their perceived aggressive nature. Whatever the reason, the Roman military increasingly showed "barbarian" traits that were once against the Roman ideal. These included valuing strength and a desire for battle. They also adopted "barbarian" strategies and customs, like the barritus (a Germanic battle cry) and the Schilderhebung (raising an elected emperor on a shield). Adopting these customs might just mean the Roman army took on useful practices, which was common. Some barbarian soldiers who joined the Roman army proudly became Roman. In some cases, the barbarian background of certain late Roman figures was completely ignored.

Religion was always an important part of being Roman. As Christianity became the main religion in the Roman Empire in late antiquity, and then the only legal faith, Christian Roman nobles had to redefine their Roman identity in Christian terms. The rise of Christianity was not ignored by conservative pagan Romans. Many of them, pressured by the growing number of anti-pagan Christians, insisted they were the only "true Romans." They said they preserved the traditional Roman religion and culture. According to the Roman statesman Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (c. 345–402), true Romans followed the traditional Roman way of life, including its ancient religions. He believed that following these religions would protect the empire from enemies, as it had in the past. Symmachus and his supporters thought Romanness had nothing to do with Christianity. It depended on Rome's pagan past and its role as the center of a vast, polytheistic (many gods) empire.

Symmachus's ideas were not popular with Christians. Some church leaders, like Ambrose, the Archbishop of Mediolanum, strongly attacked paganism and its defenders. Like Symmachus, Ambrose saw Rome as the greatest city of the Roman Empire. But he saw it as great because of its Christian present, not its pagan past. Throughout late antiquity, Romanness became more and more defined by Christian faith. This eventually became the standard. Christianity's status grew greatly when Roman emperors adopted the religion. Throughout late antiquity, the emperors and their courts were seen as the ultimate Romans.

As the Roman Empire lost control of territories to barbarian rulers, the status of Roman citizens in those areas sometimes became uncertain. People born as Roman citizens in regions that came under barbarian control could face the same prejudice as barbarians. Over the Roman Empire's history, men from almost all its provinces became emperors. So, Roman identity remained political, not ethnic, and open to people from different backgrounds. This helped the Roman state last a long time. The fall of the Western Roman Empire happened when Romans first actively excluded an influential foreign group within the empire: the barbarian generals of the 5th century. They were kept from Roman identity and the imperial throne.

Roman Identity After the Empire

Roman Identity in Western Europe

After the Western Roman Empire fell in the late 5th century, and until Emperor Justinian I's wars in the 6th century, societies in the west had mostly barbarian armies. But their civil administration and noble class were almost entirely Roman. The new barbarian rulers tried to present themselves as legitimate rulers within the Roman system. This was especially true for the rulers of Italy. The early kings of Italy, first Odoacer and then Theoderic the Great, were legally seen as viceroys (representatives) of the eastern emperor. They were part of the Roman government. Like the western emperors before them, they continued to appoint western consuls. These appointments were accepted in the east and by other barbarian kings. The imperial court in the east gave various honors to powerful barbarian rulers in the west. The barbarians saw this as making them more legitimate, and they used it to justify taking more land. In the early 6th century, Clovis I of the Franks and Theoderic the Great of the Ostrogoths almost went to war. This conflict could have led to a new western empire under either king. Worried about this, the eastern court never again gave such honors to western rulers. Instead, they began to emphasize their own exclusive Roman legitimacy, which they did for the rest of their history.

Culturally and legally, Roman identity remained important in the west for centuries. It still provided a sense of unity across the Mediterranean. Italy's Ostrogothic Kingdom kept the Roman Senate, which often controlled politics in Rome. This shows that Roman institutions and identity survived and were still respected. Barbarian kings continued to use Roman law throughout the early Middle Ages. They often issued their own law collections. In 6th-century law collections from the Visigoths in Spain and the Franks in Gaul, it's clear that many people still identified as Romans. The laws distinguished between barbarians who lived by their own laws and Romans who lived by Roman law. Even after Italy was conquered by the Lombards in the late 6th century, northern Italy continued to have Roman administration and cities. This shows that Roman institutions and values survived. It was still possible for non-citizens (like barbarians) in the west to become Roman citizens well into the 7th and 8th centuries. Several documents from the Visigoths and Franks explain the benefits of becoming a Roman citizen. There are records of rulers freeing slaves and making them citizens. Despite this, Roman identity was rapidly declining by the 7th and 8th centuries.

The Fading of Roman Identity

A major turning point for Romans in the west was the wars of Justinian I (533–555). He aimed to reconquer the lost provinces of the Western Roman Empire. During Justinian's early rule, eastern writers rewrote 5th-century history. They described the west as "lost" to barbarian invasions, rather than trying to include barbarian rulers more into the Roman world. By the end of Justinian's wars, the empire had regained control of northern Africa and Italy. But the wars were based on the idea that anything outside the eastern empire's direct control was no longer part of the Roman Empire. This meant there was no doubt that lands beyond the imperial border were no longer Roman and remained "lost to barbarians." As a result, Roman identity in the barbarian-ruled regions (Gaul, Spain, and Britain) declined sharply. During the reconquest of Italy, the Roman Senate disappeared. Most of its members moved to Constantinople. Although the senate had a legacy in the west, its end removed a group that had always set the standard for what Romanness meant. The war in Italy also divided the Roman elite there. Some liked barbarian rule, while others supported the empire and moved to imperial territory. This meant Roman identity no longer provided social and political unity.

The splitting of Western Europe into many different kingdoms made Roman identity disappear faster. The old unifying identity was replaced by local identities based on where one was from. The weakening connections also meant that while Roman law and culture continued, the language became fragmented. Latin slowly developed into what would become the modern Romance languages. Where they had once been the majority, the Romans of Gaul and Hispania slowly faded away. Their descendants adopted other names and identities. In Sub-Roman Britain, people in large cities held onto Roman identity. But rural people mixed with Germanic settlers (the Jutes, Angles, and Saxons). Once the large cities declined, Roman identity also faded in Britain.

Adopting local identities in Gaul and Hispania was more appealing because they didn't clash with the barbarian rulers' identity. For example, you couldn't be both Roman and Frankish. But you could be both Arvernian (from Auvergne) and Frankish. In Hispania, "Gothic" changed from just an ethnic identity to both an ethnic and political one. This made it easier for people to switch from identifying as Romans to identifying as Goths. There were few differences between Goths and Romans in Hispania by this point. The Visigoths no longer practiced Arian Christianity. Romans, like Goths, were allowed to serve in the military from the 6th century onwards. Although Roman identity was quickly disappearing, the Visigothic Kingdom in the 6th and 7th centuries still produced several important Roman generals, like Claudius and Paulus.

The disappearance of Romans is seen in barbarian law collections. In the Salic law of Clovis I (around 500 AD), Romans and Franks were the two main groups in the kingdom, both with clear legal statuses. A century later in the Lex Ripuaria, Romans were just one of many smaller, semi-free groups. Their legal rights were limited, and many of their former advantages were now linked to Frankish identity. Such legal arrangements would have been impossible under the Roman Empire. By Charlemagne's coronation in 800 AD, Roman identity had largely disappeared in Western Europe and held low social status. It was a bit strange: living Romans, in Rome and elsewhere, had a bad reputation. There are records of anti-Roman attacks and "Roman" being used as an insult. But the name of Rome was also a source of great political power and prestige. Many noble families (sometimes falsely claiming Roman origins) and rulers used it throughout history. By suppressing Roman identity in their lands and calling the remaining eastern empire "Greek," the Frankish state hoped to prevent the Roman people from proclaiming a Roman emperor, as the Franks proclaimed a Frankish king.

Roman Identity in the City of Rome

The people of the city of Rome continued to identify as Romans. While Rome's history was not forgotten, its importance in the Middle Ages mainly came from being the home of the pope. This view was shared by both westerners and the eastern empire. For centuries after Justinian's reconquest, when the city was still under imperial control, its people were not specially governed and had no political role in wider imperial affairs. When clashing with emperors, popes sometimes used the support of the populus Romanus ("people of Rome") to make their claims stronger. This meant the city still had some ideological importance for Romanness. Western European writers increasingly linked Romanness only with the city itself. By the late 8th century, westerners almost only used the term to refer to the people of the city. When the pope's worldly power was established through the Papal States in the 8th century, popes used the support of the populus Romanus to justify their rule.

The Roman people of the Middle Ages didn't see the eastern empire or Charlemagne's new "Holy Roman Empire" as truly Roman. They accepted that Constantinople was a continuation of Rome. But they saw easterners as Greeks who had abandoned Rome and Roman identity. The Carolingian kings, on the other hand, were seen as having more to do with the Lombard kings of Italy than the ancient Roman emperors. Medieval Romans often compared the Franks to the ancient Gauls, seeing them as aggressive and arrogant. Despite this, the Holy Roman emperors were recognized by Rome's citizens as true Roman emperors, but only because the popes supported and crowned them.

The Franks and other westerners didn't think highly of Rome's population either. Foreign writings are generally negative, describing Romans as restless and deceitful. Anti-Roman feelings lasted throughout the Middle Ages. Romans partly got their bad reputation from sometimes trying to be independent from the popes and Holy Roman emperors. Since these rulers were seen as having universal power, Romans were considered meddlers in affairs beyond their place.

Roman Identity in North Africa

Unlike other kingdoms, the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa did not pretend to be loyal to the Roman Empire. Since "Roman" implied political loyalty to the empire, the Vandal government saw it as a suspicious term. As a result, the Roman people in the kingdom rarely called themselves Roman. However, important signs of Romanness, like Roman names, following Nicene Christianity, and Latin literature, survived. Despite not using "Roman" for their people, the Vandals partly used Roman legitimacy to justify their rule. Vandal kings had marriage ties to the imperial Theodosian dynasty. But the Vandal state also tried to legitimize itself by using pre-Roman cultural elements, especially from the Carthaginian Empire. Some ancient symbols were brought back. The city of Carthage, the kingdom's capital, was heavily featured in poetry, on coins, and in a new "Carthaginian calendar." Vandal coins said Felix Karthago ("fortunate Carthage") and Carthagine Perpetua ("Carthage eternal").

The Vandals' promotion of independent African symbols deeply affected the former Roman people of their kingdom. By the time eastern empire soldiers arrived in Africa during Justinian's Vandalic War, the Romance people of North Africa no longer identified as Romans. They preferred to be called Libyans (Libicus) or Punic people (Punicus). Eastern writers at the time also called them Libyans (Λίβυες). During the Vandal Kingdom's short life, the Vandal ruling class had mixed culturally and ethnically with the Romano-Africans. By the time the kingdom fell, the only real cultural differences between "Libyans" and "Vandals" were that Vandals were Arian Christians and allowed to serve in the army. After North Africa was brought back into the empire, the eastern Roman government deported the Vandals. This soon led to the Vandals disappearing as a distinct group. Only soldiers were recorded as being deported. Since the wives and children of "Vandals" stayed in North Africa, the name at this stage seems to have mainly referred to the soldier class.

Even after North Africa was reunited with the empire, the difference between "Libyans" and "Romans" (people from the eastern empire) remained. According to the 6th-century eastern historian Procopius, the Libyans were descended from Romans, ruled by Romans, and served in the Roman army. But their Romanness had changed too much after a century of Vandal rule. Imperial policy showed that North Africans were no longer seen as Romans. While governors in eastern provinces were often locals, the military and administrative staff in North Africa were almost entirely easterners. The imperial government's distrust of locals was not surprising. Imperial troops had been bothered by local (formerly Roman) peasants during the Vandalic War, who supported the Vandal regime. There had also been several rebellions, like those by Guntarith and Stotzas, who wanted to restore an independent kingdom. The difference between Romans and the Romance people of North Africa is also seen in foreign writings. The two groups seem not to have fully reconciled by the time the African provinces fell during the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb, ending Roman rule.

Roman Identity in the Eastern Mediterranean

People in the Eastern Mediterranean, who remained under Eastern Roman (or "Byzantine") control after the 5th century, kept "Roman" as their main identity. Most people saw themselves as Roman without a doubt. They believed their emperor ruled from Constantinople, the New Rome, which was the cultural and religious center of the Roman Empire. For centuries, when the Byzantine Empire was still large, Roman identity was stronger in the empire's core lands. But it was also strongly embraced in border regions during uncertain times. As in earlier centuries, Romans of the early Byzantine Empire were seen as a people united by being subjects of the Roman state. They were not united by shared family background (like the gens of barbarian groups). The term included all Christian citizens of the empire. Generally, it referred to those who followed Chalcedonian Christianity and were loyal to the emperor.

In Byzantine writings up to at least the 12th century, the idea of the Roman "homeland" always referred to the entire old Roman world, not just Greece or Italy. Even though the Byzantine Empire was mostly Greek-speaking, and the percentage of Greek speakers grew as the empire shrank, Western Europeans often called it a Greek empire, inhabited by Greeks. To the early Byzantines themselves, until about the 11th century, terms like "Hellenes" were seen as insulting. This was because it downplayed their Roman nature and linked them to ancient pagan Greeks, not the more recent Christian Romans. Westerners knew about Byzantium's Romanness. When they didn't want to distance themselves from the eastern empire, they often used Romani for soldiers and subjects of the eastern emperors. From the 6th to 8th century, western writers also sometimes used terms like res publica or sancta res publica for the Byzantine Empire, still linking it to the old Roman Republic. Such references stopped as Byzantine control of Italy and Rome itself weakened. The Papacy then began to use the term for its own, smaller region.

After the Muslim Conquests

As the Byzantine Empire lost its lands in Egypt, the Levant, and Italy, the Christians living in those regions were no longer recognized by the Byzantine government as Romans. This was similar to what happened with North Africans under Vandal rule. The decrease in the variety of peoples recognized as Roman meant that the term "Roman" increasingly applied only to the now dominant Greek population of the remaining territories. Since the Greek people were united by following Orthodox Christianity, spoke Greek, and believed they shared a common ethnic origin, "Roman" (Rhōmaîoi in Greek) slowly became an ethnic identity. By the late 7th century, Greek, not Latin, was called the rhomaisti (Roman way of speaking) in the east. In chronicles from the 10th century, the Rhōmaîoi started appearing as just one of the empire's ethnic groups (alongside, for example, Armenians). By the late 11th century, historical writings mentioned people being "Rhōmaîos by birth," showing that "Roman" had fully become an ethnic description. At this point, "Roman" also began to be used for Greek populations outside the empire's borders. For example, Greek-speaking Christians under Seljuk rule in Anatolia were called Rhōmaîoi, even though they resisted Byzantine attempts to bring them back into the empire. Only a few later sources kept the old view of a Roman being a citizen of the Roman world.

The capture of Constantinople by non-Roman Latin crusaders in 1204, during the Fourth Crusade, ended the continuous Roman rule from Rome to Constantinople. To prove they were still Romans after losing Constantinople, the Byzantine elite looked for other ways to define what Romans were. The leaders of the Empire of Nicaea, the Byzantine government-in-exile, mainly focused on Greek cultural heritage and Orthodox Christianity. They connected contemporary Romans to the ancient Greeks. This made Romanness even more linked to people who were ethnically and culturally Greek. Under the Nicene emperors John III (r.1222–1254) and Theodore II (r.1254–1258), these ideas went further. They clearly stated that the current Rhōmaîoi were Hellenes, descendants of the Ancient Greeks. While they saw themselves as Greek, the Nicene emperors also maintained they were the only true Roman emperors. "Roman" and "Hellenic" were not seen as opposing terms, but as parts of the same double-identity. During the rule of the Palaiologos dynasty, from the recapture of Constantinople in 1261 to the empire's fall in 1453, Hellene became less common as a self-identity. Rhōmaîoi once again became the main term used for self-description. Some Byzantine writers even went back to using "Hellenic" and "Greek" only for the ancient pagan Greeks.

After Constantinople's Fall

Rhōmaîoi continued to be the main self-name for Christian Greek people in the new Turkish Ottoman Empire after the Byzantine Empire fell. The common historical memory of these Romans wasn't about the glorious past of the old Roman Empire or Greek culture in Byzantium. Instead, it focused on stories of the fall and the loss of their Christian homeland and Constantinople. One such story was the myth that the last emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, would one day return from the dead to reconquer the city. This myth lasted in Greek folklore until the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829) and beyond.

In the early modern period, many Ottoman Turks, especially those in cities not involved in the military or government, also called themselves Romans (Rūmī, رومى). They were inhabitants of former Byzantine territory. The term Rūmī was originally used by Muslims for Christians in general, but later only for Byzantines. After 1453, the term was sometimes used by Turks for themselves. Other Islamic states and peoples also used it for Ottoman Turks. The Ottomans were also identified with Romans outside the Islamic world. 16th-century Portuguese sources called the Ottomans they fought in the Indian Ocean "rumes." The Chinese Ming dynasty called the Ottomans Lumi (魯迷), a transliteration of Rūmī, and Constantinople Lumi cheng (魯迷城, "Lumi city"). As applied to Ottoman Turks, Rūmī started to fall out of use at the end of the 17th century. Instead, the word became more and more linked only to the Greek population of the empire, a meaning it still has in Turkey today.

As applied to Greeks, the self-identity as Romans lasted longer. For a long time, there was widespread hope that the Romans would be freed and their empire restored. By the time of the Greek War of Independence, the main self-identity of Greeks was still Rhōmaîoi or Romioi.

Modern Roman Identity

The Italians of Rome still identify with the name 'Roman' today. Rome is Italy's most populated city, with about 2.8 million citizens. The Rome metropolitan area has over four million people. Since the Western Roman Empire fell, the Papacy has continued the role of the Pontifex Maximus. Governments inspired by the ancient Roman Republic have been revived in the city four times. The first was the Commune of Rome in the 12th century, formed against the Pope's worldly power. Then came the government of Cola di Rienzo, who used the titles 'tribune' and 'senator', in the 14th century. In the 18th century, a sister republic to revolutionary France restored the office of Roman consul. Finally, there was the short-lived Roman Republic in 1849, with a government based on the triumvirates of ancient Rome.

Roman self-identification among Greeks only began to decline with the Greek War of Independence. Many factors led to the name 'Hellene' replacing it. These included:

- Names like "Hellene," "Hellas," and "Greece" were already used by other European nations for the country and its people.

- The old Byzantine government was gone, so it couldn't reinforce Roman identity.

- The term Romioi became linked to Greeks still under Ottoman rule, not those fighting for independence.

So, to the independence movement, a Hellene was a brave freedom fighter, while a Roman was an idle slave under the Ottomans. The new Greek national identity focused heavily on the cultural heritage of ancient Greece, not medieval Byzantium. However, following Orthodox Christianity remained important. An identity focused on ancient Greece also helped Greece internationally. In Western Europe, the Greek War of Independence received much support due to philhellenism. This was a feeling of "civilizational debt" to classical antiquity, not actual interest in the modern country. Even though modern Greeks are more like medieval Byzantines than ancient Greeks, public interest in the revolt in Europe depended almost entirely on emotional and intellectual ties to a romanticized version of ancient Greece. Similar uprisings against the Ottomans by other Balkan peoples, like the First Serbian Uprising (1804–1814), were almost completely ignored in Western Europe.

Many Greeks, especially those outside the newly founded Greek state, continued to call themselves Romioi well into the 20th century. What Greek identity should be remained unclear for a long time. As late as the 1930s, Greek artists and writers still debated Greece's contribution to European culture. They wondered if it should come from a romantic fascination with classical antiquity, a nationalist dream of a restored Byzantine Empire, the strong Eastern influence from centuries of Ottoman rule, or something entirely new, or "Neohellenic," reminding Europe that there was not only an ancient Greece, but also a modern one. The modern Greek people still sometimes use Romioi to refer to themselves. They also use the term "Romaic" ("Roman") for their Modern Greek language. Roman identity also strongly survives in some Greek populations outside Greece itself. For example, Greeks in Ukraine, settled there as part of Catherine the Great's Greek Plan in the 18th century, maintain Roman identity, calling themselves Rumaioi. The term Rum or Rumi is also still used by Turks and Arabs as a religious term for followers of the Greek Orthodox Church, not only those of Greek ethnicity.

Most of the Romance peoples who came from the mixing of Romans and Germanic peoples after the Roman Empire's political unity broke down no longer identify as Romans. However, in the Alpine regions north of Italy, Roman identity was very strong. The Romansh people of Switzerland are descendants of these populations. They, in turn, came from Romanized Rhaetians. Most Romans in the region were absorbed by the Germanic tribes who settled there in the 5th and 6th centuries. But those who resisted assimilation became the Romansh people. In their own Romansh language, they are called rumantsch or romontsch, which comes from the Latin romanice ("Romance"). Roman identity also survives in the Romands, the French-speaking community of Switzerland, and their homeland, Romandy, which covers the western part of the country.

In some regions, the Germanic word for Romans (also used for western neighbors in general), walhaz, became a name for an ethnic group. This is seen centuries after Roman rule ended in those areas. The term walhaz is the origin of the modern word 'Welsh', meaning the people of Wales. It also led to the historical name 'Vlach', used throughout the Middle Ages and Modern Period for various Eastern Romance peoples. As self-names, Roman identification was kept by several Eastern Romance peoples. Notably, the Romanians call themselves români and their nation România. How and when Romanians adopted these names is not entirely clear. One idea is the Daco-Roman continuity theory. It suggests modern Romanians are descended from Daco-Romans who came from Roman colonization after Trajan (r.98–117) conquered Dacia. The Aromanians, also of unclear origin, call themselves by various names, including arumani, armani, aromani, and rumani. All these names come from the Latin Rōmānī. The Istro-Romanians sometimes identify as rumeri or similar terms, though these names are less common now. Istro-Romanians often identify with their native villages instead. The Megleno-Romanians also identified as rumâni in the past, but this name was mostly replaced by vlasi centuries ago. Vlasi comes from "Vlach," which in turn comes from walhaz.

See also

- List of ancient Italic peoples

- Pan-Latinism

- Romance-speaking world

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |