Cola di Rienzo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Cola di Rienzo

|

|

|---|---|

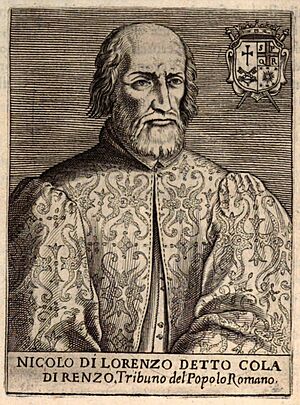

Cola di Rienzo (1646)

|

|

| Senator of Rome (De facto ruler of Rome) |

|

| In office 7 September 1354 – 8 October 1354 |

|

| Appointed by | Pope Innocent VI |

| Rector of Rome (De facto ruler of Rome) |

|

| In office 26 June 1347 – 15 December 1347 |

|

| Appointed by | Pope Clement VI |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Nicola Gabrini (son of Lorenzo)

1313 Rome, Papal States |

| Died | 8 October 1354 (aged c. 41) Rome, Papal States |

| Political party | Guelph (Pro-Papacy) |

| Profession | |

Nicola Gabrini (born in 1313 – died 8 October 1354), known as Cola di Rienzo, was an Italian politician and leader. He called himself the "tribune of the Roman people."

During his time, he wanted to unite Italy. He also believed the Pope should not have political power over lands. Because of these ideas, Cola became an important figure in the 1800s. People who wanted Italy to be a single country saw him as a hero. He was seen as someone who started the idea of the Risorgimento, which was the movement to unify Italy.

Contents

Biography

Early life and career

Nicola was born in Rome to a humble family. His father was a tavern-keeper named Lorenzo Gabrini. Nicola's name was shortened to Cola, and his father's name to Rienzo. That is why he is known as Cola di Rienzo.

He spent his early years in Anagni. There, he studied many old Latin writers, historians, and poets. He learned about the great power and glory of ancient Rome. Cola dreamed of bringing his city back to its former greatness. He also wanted to get justice for his brother, who had been killed by a noble family.

Cola became a notary, which is like a legal secretary. He became quite important in Rome. In 1343, he was sent to meet Pope Clement VI in Avignon. He did his job well and impressed the Pope. Even though he spoke out against Rome's noble rulers, the Pope liked him. He even gave Cola an official job at his court.

Leader of revolt

Cola returned to Rome in April 1344. For three years, he worked on his big goal: making Rome powerful again. He gathered many supporters and made plans for a revolt.

On May 19, 1347, messengers invited people to a meeting. This meeting was to be held on the Capitol. On May 20, a Sunday, the meeting happened. Cola wore full armor and led a procession to the Capitol. He spoke to the crowd about Rome's problems and how to fix them.

He spoke with great passion about freeing Rome. New laws were announced and everyone cheered. Cola was given full power to lead this revolution. The nobles left the city or hid without a fight. A few days later, Cola took the title of "tribune." He called himself "Nicholas, severe and kind, tribune of liberty, peace and justice, and liberator of the Holy Roman Republic."

Tribune of Rome

Cola ruled Rome with strict fairness. This was very different from the chaos before. Because of his leadership, people welcomed him at St. Peter's Church. The famous poet Petrarch wrote to him. Petrarch told Cola to keep up his great work. He praised Cola for what he had done.

All the nobles had to obey Cola, even if they did not like it. The roads became safe from robbers. Cola punished criminals severely, which scared others. Many people saw him as the person who would restore Rome and Italy.

Attempt to unify Italy

In July, Cola declared that the Roman people were in charge of the empire. Before this, he had started to bring Rome's power back over other Italian cities. He wanted Rome to be the "capital of the world" again. He sent letters to cities across Italy. He asked them to send representatives to a meeting on August 1. They would discuss forming a great union led by Rome.

On that day, many representatives came. Cola then ordered Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor and his rival Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor to appear before him. He wanted to settle their dispute. The next day, they celebrated the unity of Italy. But these meetings did not lead to any real changes.

However, Cola's power was recognized in the Kingdom of Naples. Both Joan I of Naples and Louis I of Hungary asked him for help. On August 15, Cola was crowned Tribune in a grand ceremony.

End of rule

Cola then captured some nobles, including Stefano Colonna, who had spoken badly about him. But he soon let them go. His power was already starting to weaken.

Cola di Rienzo was a mix of good and bad qualities. He was smart, a good speaker, and passionate about great ideas. But he was also vain, inexperienced, and not very steady. As his flaws became more obvious, people forgot his good deeds. His grand claims just made people laugh. His government was expensive, and he had to tax the people heavily.

He angered the Pope with his pride. He also angered both the Pope and the Emperor. This was because he wanted to create a new Roman Empire where the people had all the power. In October, the Pope gave a special representative power to remove Cola and put him on trial. It was clear his rule was ending.

The exiled nobles gathered troops and started a war near Rome. Cola di Rienzo got help from Louis of Hungary. On November 20, his forces defeated the nobles in a battle. This battle was just outside Rome. Cola himself did not fight, but his main enemy, Stefano Colonna, was killed.

But this victory did not save him. He spent his time on parties and shows. Meanwhile, the Pope declared him a criminal and a heretic. On December 15, a small disturbance scared him. He gave up his power and fled from Rome. He went to Naples for safety. Then he spent over two years in a mountain monastery.

Life in captivity

After his time alone, Cola went to Prague in July 1350. He asked Emperor Charles IV for protection. He spoke against the Pope's political power. He begged the Emperor to free Italy and Rome from their rulers. But the Emperor did not listen. Charles kept Cola in prison for over a year. Then he handed him over to Pope Clement VI.

In Avignon, Cola was put on trial in August 1352. Three cardinals sentenced him to death. But the sentence was not carried out. He stayed in prison, even though Petrarch asked for his release.

In December 1352, Pope Clement died. The new Pope, Pope Innocent VI, wanted to weaken the noble rulers of Rome. He saw Cola as a useful tool for this. So, he pardoned Cola and set him free.

Senator of Rome and death

The Pope then sent Cola back to Italy with a special representative, Cardinal Albornoz. He gave Cola the title of senator. Cola gathered some soldiers on his way. He entered Rome in August 1354. People welcomed him with great joy, and he quickly regained his power.

But this second time in power was even shorter. He tried to capture a fortress but failed. He returned to Rome. There, he unfairly captured and killed a soldier named Giovanni Moriale. He did other cruel things too. Soon, he lost the people's support. Their anger grew quickly, and a riot broke out on October 8. Cola tried to speak to them, but the building he was in was set on fire. While trying to escape in disguise, the angry crowd killed him.

Legacy

In the 1300s, Cola di Rienzo was the hero of a famous poem by Petrarch.

Cola wanted to end the Pope's political power and unite Italy. In the 1800s, he became a romantic hero for people who wanted a unified Italy. He was seen as a person who dreamed of a national future. For example, in a painting by Federico Faruffini, Cola is shown thinking about the ruins of Rome. This painting suggests that his ideas were like a sacrifice for Italy's future.

Cola di Rienzo's life has been the subject of many works. These include a novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1835). There were also plays by Mary Russell Mitford (1828) and Julius Mosen (1837). He also appeared in poems by Lord Byron.

Richard Wagner's first successful opera, Rienzi (1842), was based on Bulwer-Lytton's novel. It featured Cola as the main character. At the same time, Giuseppe Verdi, who strongly supported Italian unification, also thought about creating an opera about Cola di Rienzo.

In 1873, Rome became part of the new Kingdom of Italy. A new neighborhood was built, and its main street was named "Via Cola di Rienzo." There is also a square called Piazza Cola di Rienzo. This street connects the Tiber River to the Vatican. This was a clear message to the Catholic Church, which had lost its political power. The Piazza del Risorgimento (meaning "Rebirth Square") was also placed near the Vatican.

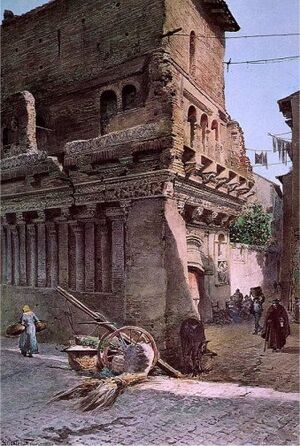

In 1877, a statue of Cola di Rienzo was put up in Rome. It stands at the bottom of the Capitoline Hill. In Rome, there is also an old brick house. It is known as "The House of Pilate," but people also traditionally call it Cola di Rienzo's house.

The Irish poet John Todhunter wrote a play about Cola di Rienzo in 1881. It was historically accurate and written in a style like Shakespeare. Polish writers also wrote plays about Cola di Rienzo. They saw similarities between his uprising and Poland's fight for independence.

His letters were published in a collection in 1890.

According to August Kubizek, a childhood friend of Adolf Hitler, Hitler had a powerful experience watching Wagner's opera Rienzi. As a teenager, this opera inspired his ideas about uniting the German people.

Some historians see Cola di Rienzo as an early example of a leader who gained power by appealing directly to the people.

See also

- Popular revolt in late medieval Europe

Images for kids

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |