History of Rome facts for kids

- Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC)

- Roman Republic (509–44 BC)

- Roman Empire (27 BC – AD 395)

- Western Roman Empire (286–476)

- Ostrogothic Kingdom (493–536, 546–547, 549–552)

Eastern Roman Empire (536–546, 547–549, 552–751)

Eastern Roman Empire (536–546, 547–549, 552–751)- Kingdom of the Lombards (751–756)

Papal States (756–1798, 1799–1809, 1814–1849, 1849–1870)

Papal States (756–1798, 1799–1809, 1814–1849, 1849–1870) First French Empire (1809–1814)

First French Empire (1809–1814) Kingdom of Italy (1870–1943, 1944–1946)

Kingdom of Italy (1870–1943, 1944–1946) Italian Republic (1946–present)

Italian Republic (1946–present)

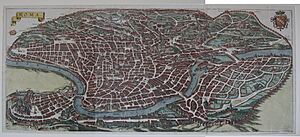

The history of Rome tells the story of the famous city of Rome and the amazing civilization of ancient Rome. Rome's past has greatly influenced the modern world, especially the history of the Catholic Church and many of today's legal systems. We can divide Rome's history into several important periods:

- Early Beginnings: This covers Rome's first people and the famous legend of its founding by Romulus.

- Kings Rule Rome: This was a time when, according to stories, seven kings ruled the city, starting with Romulus. The Etruscans also had a big influence during this period.

- The Roman Republic: Starting in 509 BC, elected leaders replaced the kings. Rome grew a lot during this time. After the Punic Wars (264 to 146 BC), Rome became the most powerful force in the Western Mediterranean.

- The Roman Empire: This period followed the Republic. It began after a civil war and the victory of Julius Caesar's adopted son, Octavian, in 27 BC.

- Decline and Change: The Western Roman Empire fell in 476 AD. Rome's power decreased, and it became part of the Eastern Roman Empire. The city became much smaller and was attacked many times.

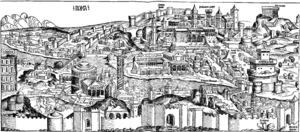

- Medieval Rome: During the Middle Ages, Rome broke away from Constantinople and the Papal States were formed. The Papacy (the Pope's power) grew, but Rome itself became less important. However, many ancient Roman buildings survived because there wasn't much new construction.

- The Roman Renaissance: In the 15th century, Rome became a major center for art and culture, taking over from Florence. This period was interrupted by the sacking of the city in 1527, but Rome continued to thrive later.

- Modern History: From the 19th century to today. Rome was taken over by Napoleon for a while. During World War II, it was bombed but later declared an open city. Since 1946, Rome has been the capital of the Italian Republic. It is now the largest city in Italy with a population of about 4.4 million people.

Contents

Rome's Ancient Story

| Rome's Key Dates | |

|---|---|

| Roman Kingdom and Republic | |

| 753 BC | Legend says Romulus founds Rome. |

| 753–509 BC | The seven Kings of Rome rule. |

| 509 BC | The Republic is created. |

| 390 BC | The Gauls attack and sack Rome. |

| 264–146 BC | The Punic Wars take place. |

| 44 BC | Julius Caesar is killed. |

Rome's Earliest History

Before Rome was Founded

Archaeologists have found signs of people living in the Rome area for at least 5,000 years. However, older sites are often hidden by layers of newer buildings and dirt. The famous legend of Romulus and Remus also makes it harder to know the exact beginnings of the city.

The traditional date for Rome's founding is April 21, 753 BC. The city and the area around it, Latium, have been continuously lived in since then. Recent digs in 2014 found a wall and pottery from the 9th and early 8th centuries BC. This shows people were on the Palatine hill even earlier, around the 10th century BC.

The Sant'Omobono Area is important for understanding how Rome grew into a city. Temples found there date back to the 7th–6th centuries BC, making them the oldest known temple remains in Rome.

The Legend of Rome's Origin

The city's name is often linked to the hero Romulus. The story says that Romulus and his twin brother Remus were the sons of a princess and the war god Mars. They were also related to the Trojan prince Aeneas.

Left by the Tiber, a she-wolf found and fed them. Later, a shepherd and his wife raised them. After taking revenge on their evil grand-uncle, they decided to build a city on the hills near the Tiber.

Romulus and Remus argued about where to build or how to interpret signs from the gods. Sadly, Romulus killed Remus. Romulus then built a walled settlement and declared it a safe place. He welcomed all kinds of people, including criminals and runaway slaves, to become citizens.

To find wives for his citizens, Romulus invited neighboring tribes to a festival. The Romans then famously abducted many young women. After a war with the Sabines, Romulus shared power with the Sabine king. Romulus also chose 100 important men to form the Roman Senate, who advised him. These men were called "fathers" (patres), and their families became the patricians.

How the City Formed

Rome started as small farming villages on the Palatine Hill and other nearby hills. It was about 30 kilometers from the Tyrrhenian Sea, on the south side of the Tiber. The Tiber River here has a bend with an island where people could cross. This location made Rome a perfect spot for trade routes along the river and for travelers going north and south.

Archaeological finds show two fortified settlements existed in the 8th century BC. These were Rumi on the Palatine Hill and Titientes on the Quirinal Hill. These were just a few of many communities in Latium, a plain in Italy. The origins of these Italic peoples are not fully known, but their Indo-European languages came from the east around 1500-1000 BC.

Ancient historians believed that some early Italian people were actually Greek settlers. Romans saw themselves as a mix of these early people, the Albans, and other Latins. Over time, Etruscans and other ancient Italic peoples also became citizens.

Italy's Ancient Neighbors

The people speaking Italic languages in the area included the Latins (west), Sabines (Tiber valley), Umbrians (northeast), Samnites (south), and Oscans. In the 8th century BC, two other major groups lived on the peninsula: the Etruscans in the North and the Greeks in the South.

The Etruscans lived north of Rome in Etruria (modern Tuscany). They built cities like Tarquinia and Veii. They greatly influenced Roman culture, even giving names to some mythical Roman kings. Most of what we know about them comes from their tombs and grave goods.

The Greeks founded many colonies in Southern Italy between 750 and 550 BC. Romans later called this area Magna Graecia. Important Greek cities included Cumae, Naples, and Taranto.

Etruscan Influence on Rome

After 650 BC, the Etruscans became very powerful in Italy. Roman tradition says that Rome was ruled by seven kings from 753 to 509 BC. The last three kings were said to be Etruscan or partly Etruscan. Their names, like Tarquinius Priscus, suggest they came from the Etruscan town of Tarquinia.

Historians like Livy wrote that Rome had seven kings. However, modern scholars doubt some of these early stories. Many of Rome's old records were destroyed when the Gauls attacked the city in 390 BC. So, we must be careful with accounts of the early kings.

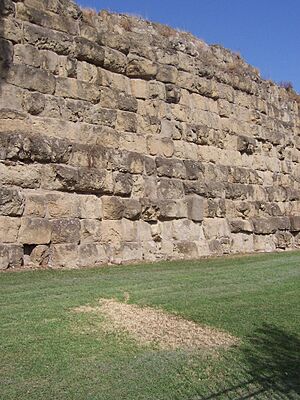

Some historians believe Rome was under Etruscan influence for about a century. During this time, important structures like the Pons Sublicius bridge and the Cloaca Maxima (a large sewer) were built. Etruscans were known as great engineers. They had a huge impact on Roman development, second only to the Greeks.

As Etruscan power declined, Rome rebelled and gained independence around 500 BC. Rome also changed from a monarchy (rule by kings) to a republic. This new system was based on a Senate made up of nobles, and assemblies where free men could participate and elect leaders each year.

The Etruscans left a lasting mark on Rome. Romans learned how to build temples from them. The Etruscans might have also introduced the worship of three main gods: Juno, Minerva, and Jupiter. However, Rome remained mostly a Latin city and was also influenced by Greek cities in the South through trade.

The Roman Republic Rises

The early stories of the Roman Republic (before about 300 BC) are often seen as legends. The Roman Republic officially lasted from 509 BC to 27 BC. After 500 BC, Rome joined with other Latin cities to defend against attacks from the Sabines. Rome won the Battle of Lake Regillus in 493 BC, regaining its power over the Latin lands.

After many struggles, Rome's power became strong by 393 BC. They defeated the Volsci and Aequi. In 394 BC, they also conquered Veii, a threatening Etruscan neighbor. Etruscan power then became limited, and Rome became the main city in Latium.

Rome also made a treaty with the city-state of Carthage in 509 BC. This treaty set out their areas of influence and trade rules.

Rome's first enemies were nearby hill tribes and the Etruscans. As Rome grew and won more battles, new enemies appeared. The fiercest were the Gauls, who controlled much of Northern Europe, including parts of Italy.

In 387 BC, the Senones, a Gaulish tribe led by Brennus, attacked and burned Rome. They had defeated the Roman army at the Battle of the Allia. The Senones then left Rome after sacking it.

After this, Rome quickly rebuilt and went on the attack. They conquered more Etruscan lands and took territory from the Gauls in the north. By 290 BC, Rome controlled more than half of the Italian peninsula. In the 3rd century BC, Rome also brought the Greek cities in the south under its control.

Rome faced constant wars. The doors of the temple of Janus were only closed twice during the Republic, meaning Rome was almost always at war. Rome also had a big social problem called the Conflict of the Orders. This was a struggle between the Plebeians (common people) and Patricians (rich families). The Plebeians wanted equal political rights.

This conflict began in 494 BC when the Plebeians left the city in protest. This led to the creation of the Plebeian Tribune office, giving the common people real power.

By the 3rd century BC, Rome was the most important city in Italy. During the Punic Wars against Carthage (264–146 BC), Rome became the capital of an overseas empire. From the 2nd century BC, Rome's population grew rapidly. Farmers, forced off their land by large, slave-run farms, moved to the city.

Winning the First Punic War gave Rome its first two provinces outside Italy: Sicily and Sardinia. Parts of Spain followed. In the 2nd century BC, Romans became involved in the Greek world. The Greek kingdoms were declining, weakened by civil wars.

Romans admired Greek culture. The Greeks saw Rome as a helpful ally. Soon, Roman armies were invited to Greece. In less than 50 years, all of mainland Greece was under Roman control. In 146 BC, the Roman general Lucius Mummius destroyed Corinth, ending free Greece. In the same year, Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus destroyed Carthage, making it a Roman province.

Rome continued its conquests in Spain and gained territory in Asia. Around 100 BC, a new threat appeared: Germanic tribes like the Cimbri and Teutones. Gaius Marius became consul five times and won two major battles. He also reformed the Roman army, making it stronger for centuries.

The last 30 years of the Republic were filled with serious internal problems. The Social War (between Rome and its allies) and slave uprisings were tough conflicts in Italy. These forced Romans to change how they treated their allies. Rome had become a huge power with great wealth from conquered people. Rome's allies felt unfairly treated because they fought for Rome but weren't citizens. Even though they lost the war, they eventually gained citizenship.

However, the growth of the Roman Empire created new problems. The old Republic's political system, with its elected leaders and shared power, couldn't handle them. Sulla's civil war and his dictatorship, and the rise of powerful generals like Pompey and Julius Caesar, showed this. In 49 BC, Julius Caesar, after conquering Gaul, crossed the Rubicon River with his army. This started a civil war with Pompey. Caesar defeated his opponents and ruled Rome for four years.

After Caesar was killed in 44 BC, the Senate tried to bring back the Republic. But Caesar's adopted son, Octavian, and his general, Mark Antony, defeated the Republic's supporters.

From 44 to 31 BC, Octavian and Mark Antony fought for power. Finally, in 31 BC, Octavian won a naval battle at Actium. He became the sole ruler of Rome and its empire. This date marks the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Principate (the early Roman Empire).

The Roman Empire's Glory and Fall

| Rome's Imperial Timeline | |

|---|---|

| Roman Empire | |

| 44 BC – AD 14 | Augustus starts the Empire. |

| AD 64 | The Great Fire of Rome during Nero's rule. |

| 69–96 | Flavian dynasty builds the Colosseum. |

| 3rd century | Crisis of the Third Century; Baths of Caracalla and Aurelian Walls built. |

| 284–337 | Diocletian and Constantine; first Christian churches built. Rome is replaced by Constantinople as capital. |

| 395 | The Empire splits into Western and Eastern Roman Empire. |

| 410 | The Goths under Alaric sack Rome. |

| 455 | The Vandals under Gaiseric sack Rome. |

| 476 | The Western Empire falls; last emperor Romulus Augustulus is removed. |

The Early Empire

By the end of the Republic, Rome was a grand city, fitting for the capital of an empire. It was the largest city in the world, with estimates of its population ranging from 1 to 2 million people. This grandeur grew even more under Augustus, the first emperor. He finished Caesar's projects and added his own, like the Forum of Augustus. He famously said he found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble. Later emperors also added to the city's beauty. In AD 64, during Nero's rule, the Great Fire of Rome destroyed much of the city, but it also allowed for new construction.

Rome was a city that depended on support from the government. About 15-25% of its grain supply was paid for by the central government. Trade and industry were less important than in other cities like Alexandria. This meant Rome needed goods and food from other parts of the Empire to feed its huge population, paid for by taxes. Without this support, Rome would have been much smaller.

Rome's population started to shrink after its peak in the 2nd century. By the end of that century, during Marcus Aurelius's reign, a plague killed many people daily. Marcus Aurelius died in 180 AD, marking the end of the "Five Good Emperors" and a period of peace called the Pax Romana. His son, Commodus, became emperor, and this is often seen as the start of the Western Roman Empire's decline. By the time the Aurelian Walls were finished in AD 273, Rome's population was only around 500,000.

Challenges in the 3rd Century

Starting in the early 3rd century, things changed for the worse. The "Crisis of the Third Century" brought disasters and political problems that almost caused the Empire to collapse. The new threat of barbarian invasions led Emperor Aurelian to build a massive wall around Rome in 273 AD. This wall was almost 20 kilometers long. Rome remained the official capital, but emperors spent less and less time there. By the end of the 3rd century, Rome lost its main role as the Empire's administrative capital. Later, Western emperors ruled from cities like Milan or Ravenna. In 330 AD, Constantine I created a second capital at Constantinople.

Christianity Comes to Rome

Christianity arrived in Rome during the 1st century AD. For the first two centuries, Roman authorities often saw Christianity as just another Jewish group. No emperor made general laws against Christians, and any persecutions were usually carried out by local officials. Emperor Trajan even told a governor not to actively seek out Christians.

Historians like Suetonius mentioned that during Nero's rule, Christians were punished for their "new and mischievous superstition." Tacitus reported that after the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64, Nero blamed Christians to deflect suspicion from himself.

Diocletian led the most severe persecution of Christians from 303 to 311 AD. But Christianity had spread too widely to be stopped. In 313 AD, the Edict of Milan made tolerance for Christians official. Constantine I became the first Christian emperor. In 380 AD, Theodosius I made Christianity the official religion of the Empire.

Under Theodosius, visits to pagan temples were forbidden. The eternal fire in the Temple of Vesta was put out, and the Vestal Virgins were disbanded. Theodosius also refused to bring back the Altar of Victory to the Senate House.

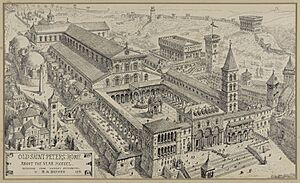

The Empire becoming Christian made the Bishop of Rome (later called the Pope) the most important religious leader in the Western Empire. Rome kept its historical importance, and this period saw a last burst of building. Constantine's predecessor Maxentius built a basilica in the Roman Forum. Constantine himself built the Arch of Constantine and the largest baths. Constantine also supported the first official Christian buildings in the city. He gave the Lateran Palace to the Pope and built the first great church, the old St. Peter's Basilica.

Barbarian Attacks and the Western Empire's Fall

Rome was still a stronghold of paganism, led by rich aristocrats. However, the new walls didn't stop the city from being sacked. Alaric's Goths sacked Rome on August 24, 410 AD. Then Geiseric's Vandals sacked it on June 2, 455 AD. Even general Ricimer's unpaid Roman troops sacked it on July 11, 472 AD. The sack of 410 AD was a major event in the decline of the Western Roman Empire.

The damage from these sackings might have been exaggerated. Rome's population had already started to decline from the late 4th century. However, the decline sped up after the Vandals captured North Africa. Rome could no longer get grain from Africa, and many people fled.

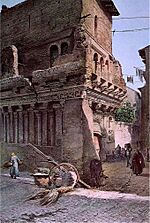

By the end of the 6th century, Rome's population was only about 30,000. People destroyed many ancient monuments, taking stones from temples and burning statues to make lime for building. New churches were often built using materials from old pagan temples. For example, the first Saint Peter's Basilica used materials from the abandoned Circus of Nero.

Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Rule

In 480 AD, the last Western Roman emperor was killed. A general named Odoacer declared loyalty to the Eastern Roman emperor Zeno. Odoacer and later the Ostrogoths ruled Italy almost independently from Ravenna. The Senate still managed Rome, and the Pope often came from a senatorial family. This continued until 535 AD.

The Eastern Roman emperor, Justinian I, sent his general Belisarius to Italy. Belisarius recaptured Rome in 536 AD. The Eastern Romans defended the city in a year-long siege against the Ostrogoths.

However, the Goths fought back. On December 17, 546 AD, the Ostrogoths under Totila recaptured and sacked Rome. Belisarius soon got the city back, but the Ostrogoths took it again in 549 AD. Finally, general Narses captured Rome from the Ostrogoths for good in 552 AD. This ended the Gothic Wars, which had ruined much of Italy.

The constant fighting left Rome in terrible condition. It was almost abandoned, and many low-lying areas became unhealthy swamps. The aqueducts, which brought water, were mostly broken. The population shrank to less than 50,000 people.

Justinian I provided money to fix public buildings and aqueducts, but it wasn't always enough. He also supported scholars and doctors, hoping more young people would get an education. After the wars, the Senate was brought back, but it was supervised by Eastern Roman officials.

However, the Pope became one of the most important religious figures in the Byzantine Roman Empire. He was more powerful locally than the remaining senators or Byzantine officials. Over time, the Church took over many of the remaining properties of the rich families and the local Byzantine administration.

The invasion of the Lombards in 568 AD further weakened Imperial control in Italy. They captured many regions, leaving Imperial authority only in small coastal areas like Rome and Ravenna. In 578 and 580 AD, the Senate had to ask for help against the Lombards.

Maurice (582–602 AD) made an alliance with the Franks. Frankish armies invaded Lombard territories several times. Rome suffered a terrible flood in 589 AD, followed by a plague in 590 AD. Legend says an angel appeared over Castel Sant'Angelo as Pope Gregory I prayed, signaling the end of the plague. Rome was safe from capture.

The new Lombard King, Agilulf, made peace with the Franks and attacked Naples and Rome in 592 AD. With the Emperor busy elsewhere, Pope Gregory I started peace talks. A treaty was signed in 598 AD.

The power of the Bishop of Rome grew even more under Emperor Phocas (602–610 AD). Phocas recognized the Pope's leadership over the Patriarch of Constantinople. He also gave the Pope the Pantheon, saving it from destruction.

During the 7th century, many Byzantine officials and churchmen came to Rome. This made both the local rich families and church leaders mostly Greek-speaking. Rome's population, attracting pilgrims, might have grown to 90,000. However, this didn't always mean peace between Rome and Constantinople. Popes sometimes faced pressure if they disagreed with Constantinople's religious views. In 653 AD, Pope Martin I was even exiled.

In 663 AD, Constans II visited Rome, the first emperor in two centuries. He stripped buildings of metal to use for weapons against the Saracens. For the next 50 years, Rome and the Papacy preferred Byzantine rule. This was partly because the alternative was Lombard rule, and Rome's food came from Papal lands in the Empire, especially Sicily.

Rome in the Middle Ages

| Rome's Medieval Timeline | |

|---|---|

| Medieval Rome | |

| 772 | Lombards briefly take Rome; Charlemagne liberates it. |

| 800 | Charlemagne crowned Holy Roman Emperor in St. Peter's Basilica. |

| 846 | Saracens sack St. Peter's. |

| 852 | Leonine Walls are built. |

| 962 | Otto I crowned Emperor by Pope John XII. |

| 1084 | The Normans sack Rome. |

| 1144 | The Commune of Rome is created. |

| 1300 | First Jubilee by Pope Boniface VIII. |

| 1309 | Pope Clement V moves the Holy Seat to Avignon. |

| 1377 | Pope Gregory XI moves the Holy Seat back to Rome. |

Rome Breaks with Constantinople

In 727 AD, Pope Gregory II refused to accept the decrees of Emperor Leo III. These decrees promoted the Emperor's iconoclasm, which meant destroying religious images. Leo tried to kidnap the Pope, but Lombard forces stopped him. Byzantine general Eutychius successfully captured Rome in 728 AD, bringing it back into the empire.

On November 1, 731 AD, Gregory III held a council to excommunicate (kick out of the church) the iconoclasts. The Emperor reacted by taking large Papal lands in Sicily and Calabria. He also transferred church areas from the Pope to the Patriarch of Constantinople. Despite these tensions, Gregory III still supported the Emperor against outside threats.

During this time, the Lombard kingdom grew stronger under King Liutprand. In 730 AD, he attacked the Roman countryside to punish the Pope. The Pope was protected by Rome's walls but couldn't do much against the Lombard king. New protectors were needed. Gregory III was the first Pope to ask for help from the Frankish Kingdom, led by Charles Martel.

Liutprand's successor, Aistulf, was even more aggressive. He conquered Ravenna, ending the Exarchate of Ravenna. Rome seemed to be his next target. In 754 AD, Pope Stephen II went to France to name Pippin the Younger, King of the Franks, as "protector of Rome." Pippin and the Pope crossed the Alps and defeated Aistulf. However, Aistulf didn't keep his promises and besieged Rome in 756 AD. The Lombards left when they heard Pippin was returning to Italy. This time, Pippin gave the Pope the promised lands, and the Papal States were born.

In 771 AD, the new Lombard King, Desiderius, tried to conquer Rome. But Pope Hadrian I called Charlemagne to help. Charlemagne defeated Desiderius in 773 AD, ending the Lombard Kingdom. Rome then became part of a new, larger political system.

Many remains from this period, along with a museum about Medieval Rome, can be seen at Crypta Balbi in Rome.

The Holy Roman Empire Begins

On April 25, 799 AD, Leo III was attacked by nobles who disliked him. Leo fled to the King of the Franks, Charlemagne. In November 800 AD, Charlemagne came to Rome with a strong army. He held a trial to decide if Leo III should remain Pope. On December 25, 800 AD, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor in St. Peter's Basilica.

This event forever separated Rome's loyalty from Constantinople. It created a rival empire that covered most of Christian Western Europe.

After Charlemagne's death, the new empire faced problems. The Church in Rome also had to deal with the growing power of the city's own people. They believed Romans had the right to elect the Western Emperor. A famous fake document, the Donation of Constantine, claimed to give the Pope power over Rome. But this was often disputed. Only the strongest Popes could truly control Rome. The main weakness of the Papacy in Rome was the need to elect new popes. Rich noble families soon gained a lot of influence in these elections. Neighboring powers, like the Duchy of Spoleto and Toscana, and later the Emperors, used this weakness to their advantage.

Rome's Commune and New Leaders

From 1048 to 1257, the Pope faced growing conflicts with leaders and churches of the Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire. This led to the East-West Schism, splitting the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church. From 1257 to 1377, the Pope lived outside Rome, in places like Avignon. When the Popes returned to Rome, it was followed by the Western Schism, where there were two or even three Popes at once.

During this time, the Church attracted pilgrims and money from all over the Christian world. Even with a population of only 30,000, Rome became a city of consumers, depending on the Church's government. Meanwhile, Italian cities gained more independence, led by new families of traders and merchants. After the Normans sacked Rome in 1084, powerful families like the Frangipane and Pierleoni family helped rebuild the city. Their wealth came from trade and banking.

Inspired by nearby cities, Romans began to seek more freedom from papal authority. In 1143, led by Giordano Pierleoni, Romans rebelled against the nobles and Church rule. The Senate and the Roman Republic, called the Commune of Rome, were reborn. A preacher named Arnaldo da Brescia spoke out against church property and its involvement in worldly matters. The revolt continued until 1155, but it left a lasting mark on Rome's government.

12th-century Rome was very different from the powerful empire of 700 years before. The new Senate struggled to survive. It often switched its support between the Pope and the Holy Roman Empire depending on the political situation. In 1167, Roman troops were defeated by imperial forces in a war with Tusculum. Luckily, a plague soon scattered the winning enemies, saving Rome.

In 1188, Pope Clement III finally recognized the new communal government. The Pope had to pay large sums to the communal officials, and the 56 senators became papal vassals. The Senate often had problems governing, and sometimes a single Senator took charge, leading to unfair rule.

Rival Families and Papal Power

In 1204, Rome's streets were again in chaos. A fight between Pope Innocent III's family and the powerful Orsini family caused riots. Many ancient buildings were destroyed as rival groups used machines to attack each other's towers.

The struggle between the Popes and Emperor Frederick II (who was also king of Naples and Sicily) saw Rome support the Ghibellines. Frederick sent a special wagon he had won in battle to Rome as a gift.

In 1234, during another revolt against the Pope, Romans led by Senator Luca Savelli sacked the Lateran. Savelli was the father of Honorius IV, but family ties didn't always mean loyalty back then.

Rome never became a stable, independent state like Florence or Milan. Constant fights between noble families (Savelli, Orsini, Colonna), the Popes' unclear position, and the people's pride in their past (but focus on immediate gain) prevented this.

In 1252, Romans tried to copy other successful cities by electing a foreign Senator, Brancaleone degli Andalò from Bologna. He tried to bring peace by suppressing powerful nobles (destroying about 140 towers), reorganizing workers, and creating new laws. Brancaleone was tough but died in 1258, and most of his reforms didn't last. Five years later, Charles I of Anjou, King of Naples, was elected Senator.

Pope Nicholas III, an Orsini, was elected in 1277. He moved the Popes' seat from the Lateran to the more defensible Vatican. He also ordered that no foreigner could be Senator of Rome. As a Roman, he had himself elected Senator. This made the city side with the Pope again.

Popes Leave Rome and Return

The next Pope, Boniface VIII, was a Roman from the Caetani family. He fought against his family's rivals, the Colonna, and tried to make the Holy See supreme. In 1300, he held the first Jubilee, which brought many pilgrims and boosted Rome's economy. In 1303, he founded the first University of Rome. Boniface died in 1303 after being humiliated, which showed the growing power of the King of France over the Papacy. This marked another period of decline for Rome.

Boniface's successor, Clement V, never came to Rome. This started the "Avignon captivity," where Popes lived in Avignon for over 70 years. This made local powers in Rome independent, but they were unstable. Without the Church's income, Rome fell into decay. For more than a century, no major new buildings were built. Many monuments, even churches, fell into ruin.

Cola di Rienzo and the Pope's Return

Despite its decline, Rome still had spiritual importance. In 1341, the famous poet Petrarca came to Rome to be crowned Poet laureate. Nobles and common people alike demanded the Pope's return. Among the many who went to Avignon was Cola di Rienzo, a strange but powerful speaker. On May 20, 1347, he took control of the Capitoline Hill with an excited crowd.

His rule was short but aimed to bring back the glory of Ancient Rome. He took the title of "tribune," like the ancient Roman officials. Cola even saw himself as equal to the Holy Roman Emperor. He gave Roman citizenship to all Italian cities and planned to elect a Roman emperor for Italy. This was too much. The Pope called him a heretic, and the people and nobles turned against him. On December 15, he was forced to flee.

In August 1354, Cola returned as "senator of Rome," helping the Pope regain control of the Papal States. But the tyrannical Cola became unpopular again due to his wild behavior and high taxes. In October, he was killed in a riot started by the powerful Colonna. In April 1355, Emperor Charles IV came to Rome for his coronation. His visit disappointed citizens because he had little money and left quickly.

With the emperor gone, Cardinal Albornoz gained some control over Rome. The city was mostly independent, with senators chosen by the Pope. The Senate council included judges, notaries, knights, and armed men. Albornoz had suppressed the old noble families, and the "democratic" party felt strong enough to start wars. In 1362, Rome declared war on Velletri, which led to a civil war.

On October 16, 1367, Pope Urban V finally visited Rome. During his stay, Emperor Charles IV was crowned again. The Byzantine emperor John V Palaeologus also came to Rome to ask for a crusade against the Ottoman Empire, but it was in vain. Urban didn't like Rome's unhealthy air and sailed back to Avignon in 1370. His successor, Gregory XI, planned to return in 1372, but French cardinals stopped him.

Finally, on January 17, 1377, Gregory XI brought the Holy See back to Rome.

Challenges and Rebirth

The strange behavior of Pope Urban VI, Gregory's Italian successor, caused the Western Schism in 1378. This split in the Church stopped any real improvements in decaying Rome. The 14th century, with the Popes absent in Avignon, was a time of neglect and misery for Rome. Its population dropped to its lowest point.

When Gregory XI returned to Rome in 1377, he found a city in chaos. There were fights between nobles and common people, and his power was more formal than real. Four decades of instability followed, marked by local power struggles and the great Western Schism. Finally, Martin V was elected Pope. He restored order and laid the groundwork for Rome's rebirth.

In 1433, the Duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti, signed a peace treaty. He then sent soldiers to attack the Papal States because Eugene IV had supported his enemies.

The Milanese soldiers continued their destruction despite the Pope's efforts. This led Romans to create a Republican government on May 29, 1434. Eugene left the city a few days later.

However, the new government couldn't rule the city well. Their problems and violence soon made them unpopular. Rome was returned to Eugene's control on October 26, 1434. After some changes in leadership, Eugene returned to Rome on September 28, 1443.

Rome in the Renaissance

| Rome's Renaissance Timeline | |

|---|---|

| Renaissance and Early Modern Rome | |

| 1420s–1519 | Rome becomes a center of the Renaissance. New St. Peter's Basilica and Sistine Chapel built. |

| 1527 | The Landsknechts sack Rome. |

| 1555 | The Ghetto is created for Jews. |

| 1585–1590 | City reforms under Pope Sixtus V. |

| 1626 | The new St. Peter's Basilica is dedicated. |

| 1638–1667 | Baroque era with Bernini and Borromini. Rome has 120,000 people. |

The second half of the 15th century saw the Italian Renaissance move from Florence to Rome. The Popes wanted Rome to be grander than other Italian cities. They built amazing churches, bridges, and public spaces, including a new Saint Peter's Basilica, the Sistine Chapel, and Piazza Navona. Popes also supported great artists like Michelangelo, Raphael, and Botticelli.

Under Pope Nicholas V, who became Pope in 1447, the Renaissance truly began in Rome. He was the first Pope to bring scholars and artists to the Roman court.

In 1449, Nicholas announced a Jubilee for the next year, which brought many pilgrims to Europe. So many people came that in December, about 200 died on Ponte Sant'Angelo, either crushed or drowned. Later that year, the Plague returned, and Nicholas fled.

Nicholas brought stability to the Pope's power. He ruthlessly stopped a plot to bring back the Republic in 1453. Nicholas also worked on rebuilding Rome with Leon Battista Alberti, including starting the new St. Peter's Basilica.

Nicholas's successor, Calixtus III, focused on his nephews instead of culture. The next Pope, Pius II, was a great scholar but did little for Rome. He was the first Pope to use guns in a campaign against rebel nobles in 1461. The reign of Pope Paul II (1464–1471) is remembered for bringing back the Carnival, which became very popular in Rome.

Much more important was the time of Pope Sixtus IV, considered the first Pope-King of Rome. He used his power to help his relatives and fought against powerful Roman families. Sixtus spent a lot of money on wars and intrigues, but he was also a great supporter of art. He reopened an academy, reorganized the Vatican Library, and restored churches and streets. His main project was the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican Palace. Famous artists like Sandro Botticelli, Pietro Perugino, and Michelangelo decorated it, making it one of the world's most famous monuments. Sixtus died in 1484.

Chaos, corruption, and favoritism appeared under his successors, Innocent VIII and Pope Alexander VI (1492–1503). Alexander faced Charles VIII of France, who invaded Italy in 1494 and entered Rome. The Pope had to hide in Castel Sant'Angelo. Alexander skillfully gained the king's support, but then joined an anti-French league, forcing Charles to flee.

Alexander, who favored his ruthless son Cesare, made Rome unsafe. Streets were controlled by lawless groups, especially at night. Cesare himself committed murders.

The Renaissance greatly changed Rome's appearance. Works like Michelangelo's Pietà and the frescoes in the Borgia Apartment were created. Rome reached its peak of splendor under Pope Julius II (1503–1513) and his successors, Leo X and Clement VII. For 20 years, Rome was the world's greatest art center. The old St. Peter's Basilica was torn down, and a new one began. Artists like Bramante and Raphael worked in Rome. Michelangelo started decorating the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Rome became more of a Renaissance city, with many feasts, races, and parties. Its economy was strong, with many bankers. Raphael also championed the preservation of ancient ruins.

The Sack of Rome (1527)

In 1527, the policies of Pope Clement VII led to the terrible sacking of the city by Emperor Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor's troops. After about 1,000 defenders were killed, the city was looted for days. Many citizens were killed or fled. Only 42 of 189 Swiss Guards survived. The Pope himself was imprisoned for months. This sack ended one of Rome's most brilliant eras.

The 1525 Jubilee was a failure, as Martin Luther's criticisms had spread hatred against the Pope's greed. Rome's prestige was challenged by churches in Germany and England leaving the Catholic Church. Pope Paul III (1534–1549) tried to fix things by calling the Council of Trent. He was also very nepotistic, even creating a duchy for his son from Papal lands. He continued to support art, including Michelangelo's Last Judgment, and asked him to renovate the Campidoglio. After the sack, he also had the architect Giuliano da Sangallo the Younger strengthen the walls of the Leonine City.

The Counter-Reformation

Pope Paul IV, elected in 1555, was against Spain. His policies led to Spanish troops besieging Rome in 1556. Paul made peace but had to accept the power of Philip II of Spain. He was a very unpopular Pope. After his death, angry crowds burned the Holy Inquisition's palace and destroyed his statue.

Pope Paul's Counter-Reformation ideas were clear. He ordered a central area of Rome, around the Porticus Octaviae, to be made into the famous Roman Ghetto. This was a very small area where the city's Jews were forced to live separately. They had to stay in the Sant'Angelo district and were locked in at night. The Pope also made Jews wear special yellow hats or veils. Jewish ghettos existed in Europe for over 300 years.

The Counter-Reformation gained speed under later Popes, Pope Pius IV and Pope Pius V. Pius V removed all pomp from the court, expelled jesters, and made cardinals and bishops live in the city. Blasphemy and living with someone without being married were severely punished. The Inquisition's power grew, and its prison space increased. During this time, Michelangelo opened the Porta Pia and turned the Baths of Diocletian into the beautiful basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri.

The reign of Gregory XIII was seen as a failure. He tried to be milder than Pius V, which led to more crime in Rome's streets. The writer Montaigne said that "life and goods were never as unsure as at the time of Gregorius XIII."

Pope Sixtus V (1585–1590) was very different. His short reign is remembered as one of the most effective in modern Rome's history. He was even tougher than Pius V, earning nicknames like "punisher of the mad" and "Iron Pope." Sixtus greatly reorganized the Papal States' government and cleaned up Rome's streets, punishing criminals, dueling, and other bad behavior. Even nobles and cardinals weren't safe from his police.

The money from taxes, which was no longer wasted, allowed for ambitious building projects. Old aqueducts were fixed, and a new one, the Acquedotto Felice, was built. New houses were built in empty areas, and old houses in the city center were destroyed to create new, wider streets. Sixtus wanted to make Rome a better place for pilgrimages. The new streets made it easier to reach major churches. Old obelisks were moved or set up to decorate St. John in Lateran, Santa Maria Maggiore, and St. Peter's.

The Baroque Period Flourishes

In the 18th century, the Papacy reached the peak of its worldly power. The Papal States covered most of Central Italy.

Baroque and Rococo architecture thrived in Rome, with many famous works completed. Work on the Trevi Fountain began in 1732 and finished in 1762. The Spanish Steps were designed in 1735.

The arts also flourished. Palazzo Nuovo became the world's first public museum in 1734. Famous views of Rome were etched by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, inspiring many to visit the city and see the ruins.

Rome's Modern History

| Rome's Modern Timeline | |

|---|---|

| Modern Rome | |

| 1798–1814 | French occupation. |

| 1848–1849 | Roman Republic with Mazzini and Garibaldi. |

| 1870 | Rome conquered by Italian troops. |

| 1922 | March on Rome. |

| 1929 | Lateran Pacts establish Vatican City. |

| 1943 | Bombing of Rome. |

| 1960 | Rome hosts the Summer Olympics. |

| 2000 | Rome hosts the Jubilee. |

Italian Unification and Rome's Role

In 1870, the Pope's lands were in an uncertain state. Rome itself was taken by forces from Piedmont, who had united the rest of Italy. This led to the "Roman Question" between 1861 and 1929. The Popes remained in their palace, and some rights were recognized by law. But the Popes did not accept the Italian king's right to rule Rome. They refused to leave the Vatican until the issue was settled in 1929. Other countries still recognized the Holy See as a sovereign entity.

The Popes' rule was briefly interrupted by the Roman Republic in 1798, influenced by the French Revolution. During Napoleon's rule, Rome was annexed into his empire and was technically part of France. After Napoleon's fall, the Papal States were restored, except for some areas that remained part of France.

Another Roman Republic appeared in 1849, during the revolutions of 1848. Two key figures of Italian unification, Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, fought for this short-lived republic. However, the clever leadership of Camillo Benso di Cavour, Prime Minister of Piedmont-Sardinia, was also crucial for unification.

Even those who wanted a united Italy disagreed on its form. Some wanted a confederation under the Pope. Others wanted a republic. But eventually, a king and his chief minister united Italy as a monarchy.

Cavour worked to industrialize Piedmont-Sardinia to make it Italy's economic leader. He believed other states would naturally join. He sent the Piedmont army to the Crimean War to join the French and British. This created good relations with France, which would be useful later.

When Pope Pius IX returned to Rome with French help, Rome was left out of the unification process. After the Second Italian Independence War and the Mille expedition, all of Italy except Rome and Venetia was united under the House of Savoy. Garibaldi first attacked Sicily, landing with little resistance.

Cavour publicly criticized Garibaldi's actions but secretly supported him with weapons. This "real-politik" approach, where the goal justified the means, continued as Garibaldi prepared to cross to the mainland. Cavour secretly asked the British navy to let Garibaldi's troops cross, while publicly condemning him. The plan worked, and Garibaldi conquered the entire kingdom.

Cavour then allied with France to take Venetia and Lombardy. Italy and France would attack Austria, with France getting Nice and Savoy. However, France soon pulled out, angering Cavour. Only Lombardy was captured at that time.

With French troops still in Rome, Cavour worried Garibaldi might attack the Papal States and upset France. So, the Sardinian army was sent to attack the Papal States but stay outside Rome.

In the Austro-Prussian War, Italy made a deal with Prussia. Italy would attack Austria in exchange for Venetia. Prussia won the war, and Italy gained Venetia, completing its northern front.

In July 1870, the Franco-Prussian War began, and French Emperor Napoleon III could no longer protect the Papal States. Soon after, the Italian army under general Raffaele Cadorna entered Rome on September 20, after a three-hour cannon attack, through Porta Pia. The Leonine City was occupied the next day. Rome and Latium were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy after a vote on October 2.

When Rome was taken, the Italian government reportedly wanted to let Pope Pius IX keep the part of Rome west of the Tiber, known as the Leonine City, as a small Papal State. But Pius IX refused, as accepting would mean agreeing to Italy's rule over his former lands. A week after entering Rome, Italian troops had taken the entire city except for the Apostolic Palace. The city's residents then voted to join Italy. On July 1, 1871, Rome became the official capital of united Italy. From then until June 1929, the Popes had no worldly power.

The Pope called himself the "prisoner of the Vatican," even though he was free to come and go. Pius IX took steps to make the Vatican self-sufficient, like building the Vatican Pharmacy. Italian nobles loyal to the Pope became known as the Black Nobility during this time.

Kingdom of Italy and World War II

Rome became the focus of hopes for Italian reunification. In 1861, Rome was declared the capital of Italy, even though the Pope still controlled it. During the 1860s, the last parts of the Papal States were protected by French troops. Only when these troops left in 1870, due to the Franco-Prussian War, could Italian troops capture Rome. After this, Pope Pius IX declared himself a prisoner in the Vatican, and in 1871, Italy's capital moved from Florence to Rome.

Soon after World War I, Italian Fascism rose to power in Rome, led by Benito Mussolini. In 1922, Mussolini marched on the city and eventually declared a new Empire, allying Italy with Nazi Germany.

Between the world wars, Rome's population grew quickly, surpassing 1,000,000 people.

The "Roman Question" was finally solved on February 11, 1929, with the Lateran Treaty. This treaty, signed by Benito Mussolini and Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Gasparri, created the independent Vatican City State. It also gave Roman Catholicism special status in Italy.

During World War II, Rome suffered few bombings. This was because no nation wanted to endanger Pope Pius XII in Vatican City. There were some fierce fights between Italian and German troops south of the city. On June 4, 1944, Rome became the first capital city of an Axis nation to fall to the Allies. It was relatively undamaged because on August 14, 1943, the Germans declared it an "open city" and withdrew. This meant the Allies didn't have to fight their way in.

In practice, Italy didn't interfere with the Holy See inside the Vatican walls. However, they took church property in many other places, including the Quirinal Palace, which used to be the Pope's home.

Vatican City officially remained neutral during World War II. Pope Pius XII worked to prevent the bombing of Rome. He even protested when the British dropped pamphlets over Rome, saying it violated the Vatican's neutrality.

Capital of the Italian Republic Today

Rome grew a lot after the war. It was a key part of Italy's "Italian economic miracle" of rebuilding and modernization. In the 1950s and early 1960s, it became a fashionable city, known as "la dolce vita" ("the sweet life"). Famous films like Ben Hur and Roman Holiday were filmed at the city's Cinecittà Studios.

Rome's population continued to grow until the mid-1980s, reaching over 2.8 million residents. After that, the population slowly declined as more people moved to nearby suburbs. The Rome metropolitan area has about 4.4 million people today.

As Italy's capital, Rome hosts all the nation's main institutions. These include the President, the government, Parliament, major courts, and diplomatic representatives for both Italy and Vatican City. Many important international cultural, scientific, and humanitarian organizations are also in Rome.

Rome hosted the 1960 Summer Olympics. Many ancient sites, like the Villa Borghese and the Thermae of Caracalla, were used as venues. New structures were built for the Olympics, like the Olympic Stadium.

Rome's Leonardo da Vinci–Fiumicino Airport opened in 1961. Tourism brings 7–10 million visitors each year. Rome is the second most visited city in the European Union, after Paris. The Colosseum and the Vatican Museums are among the most visited places in the world. Many ancient monuments were restored for the 2000 Jubilee.

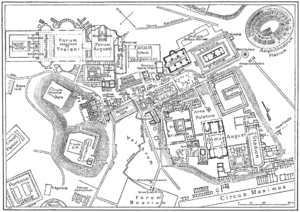

Rome's Historic Center

Today's Rome is a modern metropolis, but it clearly shows its long history. The historical center, within the ancient Imperial walls, has archaeological remains from Ancient Rome. These are always being excavated and opened to the public, like the Colosseum, the Roman Forum, and the Catacombs. There are also areas with remains from Medieval times.

You can find palaces and art from the Renaissance, and fountains, churches, and palaces from the Baroque period. There is also art and architecture from later periods. Rome has many museums, like the Musei Capitolini and the Vatican Museums.

Parts of the historical center were reorganized after Italy's Italian Unification in the late 1800s. The growing population needed new buildings and infrastructure. Major changes were also made during the Fascist period, like creating the Via dei Fori Imperiali and the Via della Conciliazione near the Vatican. These projects destroyed large parts of old neighborhoods. New districts were also founded, like EUR. So many people moved to Rome that nearby villages were included in the city.

Images for kids

-

The Tempietto (San Pietro in Montorio), a great example of Italian Renaissance architecture.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Roma para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Roma para niños

- Roman technology

- Timeline of the city of Rome

- Timeline of Roman history

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |