Joxe Azurmendi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joxe Azurmendi

|

|

|---|---|

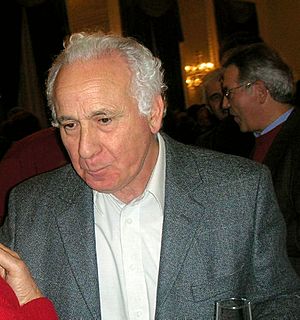

Azurmendi in 2006

|

|

| Born | 19 March 1941 Zegama, Spain

|

| Died | 1 July 2025 (aged 84) San Sebastián, Spain

|

| Alma mater | University of the Basque Country, University of Münster |

| Era | Contemporary philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Relativism |

|

Main interests

|

Modernity, Age of Enlightenment, Rationalism, Romanticism, social philosophy, political philosophy, philosophical anthropology, philosophy of language, ethics, nationalism, Basque literature |

|

Notable ideas

|

The State as secular church, morality as a political weapon |

Joxe Azurmendi Otaegi (born March 19, 1941 – died July 1, 2025) was a famous Basque writer, thinker, and poet. He wrote many articles and books. His topics included how we should live (ethics), how societies are run (politics), and how language works. He also wrote about technology, Basque literature, and general philosophy.

Azurmendi was a key member of the Jakin magazine group. He also led Jakin irakurgaiak, a publishing house that released over 40 books under his guidance. He helped translate important philosophical books into the Basque language. He also helped start the Udako Euskal Unibertsitatea (The Basque Summer University). He was a professor of Modern Philosophy at Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (The University of the Basque Country). In 2010, he was given an "honorary academic" title by Euskaltzaindia (The Basque Language Academy).

He was known for studying problems deeply rather than just looking for quick answers. Azurmendi's writings covered modern European ideas with great knowledge. He often included the ideas of European thinkers, especially German ones. Many people thought he was one of the most productive and knowledgeable thinkers in the Basque Country.

Contents

Early Life and Work

Joxe Azurmendi studied philosophy and theology. He attended universities in the Basque Country, Rome, and Münster.

In the early 1960s, he joined a cultural group linked to Jakin magazine. He was even the director when the magazine was banned by the government at the time. He continued to work closely with the magazine after it was allowed again. In Jakin, he discussed issues facing Basque society, connecting them to European ideas.

Spreading Ideas in Basque

In the early 1970s, Azurmendi focused on sharing important books in the Basque language. These books covered topics that were widely discussed in the Basque Country. These included ideas about nationhood, socialism, and international cooperation.

Teaching and Research

In the 1980s, he started teaching at The University of the Basque Country. In 1984, he completed his advanced research paper (thesis) on Jose Maria Arizmendiarrieta. Arizmendiarrieta founded the Mondragon cooperative movement. Azurmendi argued that Arizmendiarrieta wanted to unite people and society. He believed this could happen through an organization that combined socialism with a focus on the individual.

Challenging Stereotypes

In 1992, Azurmendi published a very well-known book called Espainolak eta euskaldunak (The Spanish and the Basques). This book was a response to another writer who had made negative claims about the Basque people. Azurmendi's essay showed that these claims were based on false ideas.

Major Works of the New Millennium

Around the year 2000, Azurmendi's work became even more important. In the early 2000s, he published three major books. These were Espainiaren arimaz (About the soul of Spain) (2006), Humboldt. Hizkuntza eta pentsamendua (Humboldt. Language and Thought) (2007), and Volksgeist. Herri gogoa (Volksgeist. National Character) (2008). In these books, Joxe Azurmendi shared some of his most important ideas.

In 2009, Azurmendi wrote a very personal book, Azken egunak Gandiagarekin (The last days with Gandiaga). In this book, he thought about different ways of understanding the world. He explored ideas in the philosophy of science, philosophy of religion, and philosophical anthropology. He suggested that science might not give us all the answers we need to understand the meaning of life.

Joxe Azurmendi passed away in San Sebastián on July 1, 2025, at the age of 84.

Azurmendi's Philosophical Ideas

A main theme in all of Azurmendi's philosophical work was defending the freedom to think and believe what you want. He used the idea of the "Human-Animal" to connect his thoughts. His ideas developed during a time when culture, politics, and values were changing a lot. He saw this change not as a bad thing, but as a chance for new possibilities. Because of this, his thinking always focused on protecting freedom in all areas, especially freedom of conscience and thinking.

Living with Change

Instead of avoiding these changes, his work tried to show how we can live in such times. He believed in a relativist view, meaning that there isn't just one absolute truth. Since modern times have left us without a single strong foundation, he argued against old, fixed ways of thinking (dogmatism) that society sometimes goes back to during difficult times.

He was critical of the modern state, for example. He believed it acted like a new church, trying to control people's thoughts. He also criticized how politicians sometimes use morality to avoid their responsibilities. Instead of solving real problems, they might hide behind what they claim are absolute moral rules.

Rethinking History and Ideas

Azurmendi also helped people question common ways of understanding different topics. Because he was very knowledgeable and trained in Germany, his ideas about the German Enlightenment are especially interesting. He showed that the supposed conflict between the French Enlightenment and German Romanticism might not be as clear as people thought. He offered new ways to understand these ideas.

He challenged some Spanish and French thinkers. He argued that nationalism actually started in France with thinkers like Montesquieu and Rousseau. It was then reinterpreted by German thinkers and romantics. By doing this, he questioned the idea that writers like Goethe and Humboldt were the main creators of a fixed, unchanging idea of nationalism. He also explored the differences between civic nationalism (based on shared laws and citizenship) and ethnic nationalism (based on shared ancestry or culture). Azurmendi criticized the idea that Spanish and French nationalism were based on a fixed, unchanging "essence."

Poetry and Basque Culture

Some of the deep topics Azurmendi explored in his essays first appeared in his early poetry. His poems from the 1960s showed a struggle against old traditions, old beliefs, and fixed ideas.

But we wish to be free

is that my fault?

They tried to give us a tree from Gernika,

a false blank check,

as if the desire to be free were a sin,

as if we needed an excuse for it,

but despite that, we, quite simply, wish to be free.

That is what we want, that is all.

This is the latest deception:

they have led us to believe

before from outside and now from within

that it is our responsibility to justify our wish to be free.

Manifestu atzeratua (Belated Manifesto) (1968)

He also spent a lot of his work bringing back and reinterpreting the ideas of Basque thinkers. He helped break down many old stereotypes about them. His research into Jon Mirande, Orixe, and Unamuno is particularly important. He was a writer who worked from within and for Basque culture. He said he was influenced by Basque writers from after World War II, especially concerning language. He also studied other authors like Heidegger, Wittgenstein, George Steiner, and Humboldt. The fact that all his many works are written in the Basque language fits perfectly with his ideas.

Writing Style

Joxe Azurmendi's writing combined formal language with everyday expressions. His prose was quick, sharp, and often used humor. His Basque writing was modern and standard. He showed a great understanding of the language, with rich and varied ways of expressing himself.

Awards and Recognition

- 1976: Andima Ibiñagabeitia Award for Espainolak eta euskaldunak

- 1978: Irun Hiria Award for Mirande eta kristautasuna (Mirande and Christianity).

- 1998: Irun Hiria Award for Teknikaren meditazioa (Meditations on Technique).

- 2005: Juan San Martin Award for Humboldt: Hizkuntza eta pentsamendua (Humboldt. Language and Thought).

- 2010: Euskadi Literatura Saria Award, in the essay category, for Azken egunak Gandiagarekin (The last days with Gandiaga).

- 2010: Ohorezko euskaltzaina by Euskaltzaindia.

- 2012: Eusko Ikaskuntza Award.

- 2012: Dabilen Elea Award.

- 2014: All of Joxe Azurmendi's work was made digital by The Council of Gipuzkoa.

- 2015: Euskadi Literatura Saria Award, in the essay category, for Historia, arraza, nazioa (History, race, nation).

- 2019: Joxe Azurmendi Congress hosted by Joxe Azurmendi Katedra and University of the Basque Country.

Works

The Inguma database, which tracks Basque scientific works, lists over 180 texts written by Azurmendi.

Essays

- Hizkuntza, etnia eta marxismoa (Language, Ethnics and Marxism) (1971)

- Kolakowski (Kołakowski) (1972): co-author: Joseba Arregui

- Kultura proletarioaz (About Proletarian Culture) (1973)

- Iraultza sobietarra eta literatura (The Soviet Revolution and Literature) (1975)

- Gizona Abere hutsa da (Man is Pure Animal) (1975)

- Zer dugu Orixeren kontra? (What do we have against Orixe?) (1976)

- Zer dugu Orixeren alde? (What do we have in favour of Orixe?) (1977)

- Artea eta gizartea (Art and Society) (1978)

- Errealismo sozialistaz (About Socialist Realism) (1978)

- Mirande eta kristautasuna (Mirande and Christianity) (1978)

- Arana Goiriren pentsamendu politikoa (The political thinking of Arana Goiri) (1979)

- Nazionalismo Internazionalismo Euskadin (Nationalism Internationalism in the Basque Country) (1979)

- PSOE eta euskal abertzaletasuna (The Spanish Socialist Party and Basque Nationalism) (1979)

- El hombre cooperativo. Pensamiento de Arizmendiarrieta (Cooperative Man. Arizmendiarrieta's thinking) (1984)

- Translated into Japanese as ホセ・アスルメンディ: アリスメンディアリエタの協同組合哲学 ( 東大和 : みんけん出版 , 1990) ISBN: 4-905845-73-4

- Filosofía personalista y cooperación. Filosofía de Arizmendiarrieta (Personalist philosophy and cooperation. Arizmendiarrieta's philosophy) (1984)

- Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Spengler, Miranderen pentsamenduan (Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Spengler in the thinking of Mirande) (1989)

- Miranderen pentsamendua (Mirande's thinking) (1989)

- Gizaberearen bakeak eta gerrak (War and Peace according to the Human Animal) (1991)

- Espainolak eta euskaldunak (The Spanish and the Basques) (1992)

- Translated into Spanish as Azurmendi, Joxe: Los españoles y los euskaldunes, Hondarribia: Hiru, 1995. ISBN: 978-84-87524-83-7

- Karlos Santamaria. Ideiak eta ekintzak (Karlos Santamaria. Ideas and Action) (1994)

- La idea cooperativa: del servicio a la comunidad a su nueva creación (The cooperative idea: from the community service toward its new creation) (1996)

- Demokratak eta biolentoak (The Democrats and the Violent) (1997)

- Teknikaren meditazioa (Meditations on Technique) (1998)

- Oraingo gazte eroak (The Mad Youth of Today) (1998)

- El hecho catalán. El hecho portugués (The Catalan fact. The Portuguese fact) (1999)

- Euskal Herria krisian (The Basque Country in Crisis) (1999)

- La violencia y la búsqueda de nuevos valores (The violence and the search for new values) (2001)

- La presencia de Nietzsche en los pensadores vascos Ramiro de Maeztu y Jon Mirande (The Nietzsche's presence in the Basque thinkers Ramiro de Maeztu and Jon Mirande) (2002)

- Etienne Salaberry. Bere pentsamenduaz (1903–2003) (Etienne Salaberry. About his Thinking (1903–2003)) (2003)

- Espainiaren arimaz (About the soul of Spain) (2006)

- Volksgeist. Herri gogoa (Volksgeist. National Character) (2007)

- Humboldt. Hizkuntza eta pentsamendua (Humboldt. Language and Thought) (2007)

- Azken egunak Gandiagarekin (The last days with Gandiaga) (2009)

- Bakea gudan (Peace in War) (2012)

- Barkamena, kondena, tortura (Forgiveness, Condemnation, Torture) (2012)

- Karlos Santamariaren pentsamendua (Karlos Santamaria's thinking) (2013)

- Historia, arraza, nazioa (History, race, nation) (2014)

- Gizabere kooperatiboaz (About the cooperative Human Animal) (2016)

- Hizkuntza, Nazioa, Estatua (Language, Nation, State) (2017)

- Beltzak, juduak eta beste euskaldun batzuk (Blacks, Jews and other Basques) (2018)

- Pentsamenduaren historia Euskal Herrian (History of thought in the Basque Country) (2020)

- Europa bezain zaharra (As old as Europe) (2023)

Poetry

- Hitz berdeak (Unrefined words) (1971)

- XX. mendeko poesia kaierak – Joxe Azurmendi (Books of 20th century poetry – Joxe Azurmendi) (2000), edited by Koldo Izagirre.

Articles in Journals

- Articles in the journal Jakin

- Articles in the journal Anaitasuna

- Articles in the journal RIEV

See also

In Spanish: Joxe Azurmendi para niños

In Spanish: Joxe Azurmendi para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |