Ugo Foscolo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Niccolò Ugo Foscolo

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by François-Xavier Fabre, 1813

|

|

| Born | 6 February 1778 Zakynthos (Zante), Ionian Islands, Republic of Venice, now Greece |

| Died | 10 September 1827 (aged 49) Turnham Green, now London, England |

| Resting place | Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence |

| Pen name | Didimo Chierico |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, soldier |

| Language | Italian |

| Nationality | Venetian-Greek |

| Citizenship | Venetian (1778–1799), Italian (until 1814), Britain (1814–1827) |

| Period | 1796–1827 |

| Genres | lyrical poetry, epistolary novel, literary critic |

| Literary movement | Neoclassicism, Pre-Romanticism |

| Partner | Isabella Teotochi Albrizzi (1795–1796) Isabella Roncioni (1800–1801) Antonietta Fagnani Arese (1801–1803) Fanny "Sophia" Emerytt-Hamilton (1804–1805) Quirina Mocenni Magiotti (1812–1813) |

| Children | Mary "Floriana" Hamilton-Foscolo (from Fanny Hamilton) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Ugo Foscolo (Italian: [ˈuːɡo ˈfoskolo, fɔs-]; 6 February 1778 – 10 September 1827), born Niccolò Foscolo, was an Italian writer and poet. He was also a soldier and a revolutionary.

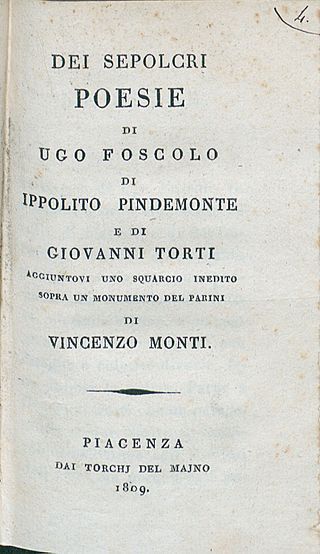

He is best known for his long poem Dei Sepolcri, written in 1807. This poem is about the importance of tombs and memories.

Contents

Early Life

Ugo Foscolo was born on the island of Zakynthos. This island was part of the Ionian Islands. His father, Andrea Foscolo, was a Venetian nobleman. His mother, Diamantina Spathis, was Greek.

In 1788, his father passed away. His father had worked as a doctor in Spalato. After his father's death, the family moved to Venice. Foscolo finished his studies at the University of Padua.

One of his teachers in Padua was Melchiore Cesarotti. Cesarotti's version of Ossian was very popular. This work influenced Foscolo's writing style. Foscolo knew both modern and Ancient Greek. In 1797, he wrote a play called Tieste. This play was quite successful.

Politics and Writing

Foscolo changed his first name from Niccolò to Ugo. The reason for this change is not known. He became very involved in the political changes happening in Venice. The Republic of Venice was falling apart.

Foscolo hoped that Napoleon would help Venice. He thought Napoleon would remove the old rulers. He wanted Napoleon to create a free republic. Foscolo even wrote a poem to Napoleon.

However, the Treaty of Campo Formio in 1797 changed everything. This treaty ended the old Republic of Venice. The French divided Venice. This was a big shock for Foscolo.

The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis

Foscolo's novel, The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis, tells a sad story. It was based on real events. The book was very popular with young Italian patriots. It showed their feelings about their country.

Writing this book helped Foscolo deal with his own sadness. He had seen his hopes for Italy shattered. But he did not give up on his country. He decided to focus on becoming a great national poet.

Life in Milan

After Venice fell, Foscolo moved to Milan. There, he became friends with an older poet, Giuseppe Parini. Foscolo admired Parini very much. In Milan, he published 12 Sonnets. These poems mixed strong emotions with a classic writing style.

Foscolo still hoped Napoleon would free Italy. He joined the French army as a volunteer. He fought in the battle of the Trebbia. He also took part in the siege of Genoa. He was wounded and captured.

After being released, he went back to Milan. He finished his novel Ortis there. He also translated works by Callimachus and started translating the Iliad. He also began translating A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy by Laurence Sterne. Foscolo also tried to propose a new unified Italian government to Napoleon.

Dei Sepolcri and Later Works

In 1807, Foscolo wrote his famous poem, Dei Sepolcri. This poem was a way for him to find comfort in the past. It talked about how important it is to remember great people. He believed that remembering heroes could inspire people.

In 1809, Foscolo became a professor at Pavia. He taught Italian speaking skills. He encouraged students to study literature. He wanted them to see how literature connects to life and country. Napoleon later ended this teaching position in all Italian universities.

Foscolo's play, Ajax, was not very successful. People thought it made fun of Napoleon. So, Foscolo had to move from Milan to Tuscany. In Florence, he wrote another play, Ricciarda. He also worked on his Ode to the Graces. He finished his translation of the Sentimental Journey in 1813.

Foscolo returned to Milan in 1813. But when the Austrians arrived, he left for Switzerland. There, he wrote a strong satire in Latin. Finally, in late 1816, he moved to England.

Life in London

Foscolo lived in London for eleven years. He was well-known in English society. He was famous for his writing and political ideas. However, he often had money problems. He was not good at managing his finances.

He wrote for important magazines like the Edinburgh Review. He also wrote about Italian writers like Dante Alighieri and Giovanni Boccaccio. His English essays on Petrarch also added to his fame.

Foscolo sometimes faced financial difficulties. This affected his standing in society. He taught Italian at the Newington Academy for Girls. This was a Quaker school.

Ugo Foscolo passed away in Turnham Green on 10 September 1827. He was buried at St Nicholas Church, Chiswick. His tomb there calls him the "wearied citizen poet."

Forty-four years after his death, his body was moved. The King of Italy asked for his remains. On 7 June 1871, he was reburied in Santa Croce in Florence. This church is like a pantheon for Italian heroes. He was laid to rest near famous figures like Niccolò Machiavelli and Galileo. This was a big national event.

Moving Foscolo's remains was part of a bigger plan. The Italian government wanted to create national heroes. These heroes would help unite the new Italian state.

Works

Poetry

- A Bonaparte liberatore (To Bonaparte the liberator) (1797)

- All'amica risanata (1802)

- Alla Musa (1803)

- Alla sera (1803)

- A Zacinto (To Zakinthos) (1803)

- In morte del fratello Giovanni (1803)

- Dei Sepolcri (Of the sepulchres) (1807)

Novels

- Ultime lettere di Jacopo Ortis (The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis) (1802)

- Il sesto tomo dell'Io (unfinished)

Plays

- Tieste (Thyestes) (1797)

- Aiace (1811)

See also

In Spanish: Ugo Foscolo para niños

In Spanish: Ugo Foscolo para niños