Etruscan language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Etruscan |

|

|---|---|

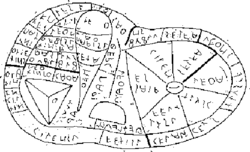

The Cippus Perusinus, a stone tablet bearing 46 lines of incised Etruscan text, one of the longest extant Etruscan inscriptions. 3rd or 2nd century BC.

|

|

| Native to | Ancient Etruria |

| Date | 700 BC |

| Region | Italian Peninsula |

| Ethnicity | Etruscans |

| Extinct | after AD 50 |

| Language family |

Tyrsenian

|

| Writing system | Etruscan alphabet |

| Linguist List | ett |

The Etruscan language was spoken by the Etruscan civilization in ancient Etruria, a region in what is now Italy. This language had an impact on Latin, the language of the Romans, but eventually, Latin took its place. We have found about 13,000 Etruscan writings, mostly short. Some of these writings are bilingual, meaning they have texts in Etruscan and another language like Latin or Ancient Greek.

Etruscan was used from about 700 BC until around 50 AD. For a long time, people wondered how it was related to other languages. Today, most experts agree it belongs to the Tyrsenian language family. This family also includes the Raetic language, spoken in the Alps, and the Lemnian language, found on the island of Lemnos. Experts believe Etruscan was a "Pre-Indo-European" language, meaning it existed in Europe before many of the languages we know today, like English or Spanish, arrived.

The Etruscan alphabet came from the Greek alphabet, specifically from a type of Greek writing used in southern Italy. This means that linguists can read the Etruscan inscriptions and know how they sounded. However, understanding what all the words mean is still a big challenge! By studying patterns, they have figured out some words and how they change in sentences.

Etruscan was an agglutinating language. This means it added many suffixes (endings) to words to change their meaning or role in a sentence, like adding "-ing" or "-ed" in English. It had a simple sound system with four main vowels and a difference between sounds like 'p' and 'ph'. The language also influenced some important words in Western Europe, such as military and person, which may have come from Etruscan.

Contents

Exploring Ancient Etruscan Writings

The Etruscans were very good at writing. We know this because about 13,000 inscriptions have been found across the Mediterranean Sea region. Most of these are short, like dedications or messages on tombs, and they date back to about 700 BC.

Ancient Roman writers mentioned that the Etruscans had many books. These books contained special religious rules and ways to predict the future. For example, the Libri Haruspicini taught how to tell the future by looking at animal organs. The Libri Fulgurales explained how to interpret lightning strikes. Another set, the Libri Rituales, likely covered Etruscan social rules and ceremonies. Sadly, almost all these books are lost. Only one book, the Liber Linteus, survived because its linen pages were used to wrap an ancient Egyptian mummy!

Around 30 BC, the Roman historian Livy noted that Roman boys used to learn Etruscan. However, by then, Greek had become the more popular language for Romans to study.

How the Etruscan Language Disappeared

Experts believe the Etruscan language died out sometime between the late 1st century BC and the early 1st century AD. This happened because Latin slowly replaced it. In areas closer to Rome, like the southern parts of Etruria, Latin took over earlier. For example, the Etruscan city of Veii was taken by Romans in 396 BC and its people became Roman.

In some northern Etruscan towns, Etruscan writing continued for a while longer. In places like Perugia, you could still see Etruscan inscriptions in the first half of the 1st century BC. Even after the language was no longer commonly spoken, some Etruscan religious ceremonies continued. These ceremonies might have still used Etruscan names for gods and some parts of the language.

Even the Roman Emperor Claudius, who lived from 10 BC to 54 AD, was interested in Etruscan history. He wrote a book about it, which is now lost. This suggests that a few educated Romans still knew about the language, even if they couldn't speak it fluently.

Etruscan left its mark on Latin. Many Etruscan words and names were borrowed by the Romans. Some of these words, like vulture, trumpet, and people, are still used in modern languages today.

Where Etruscan Was Spoken

Etruscan writings have been found in many parts of central and northern Italy. This includes the region we now call Tuscany, which gets its name from the Etruscans (tuscī in Latin). It was also spoken north of Rome in Latium, west of the Tiber River in Umbria, and in the Po Valley and Campania.

Beyond Italy, some Etruscan inscriptions have been discovered in places like Corsica, parts of France (ancient Gallia Narbonensis), Greece, and the Balkans. However, most of the Etruscan writings are found in Italy.

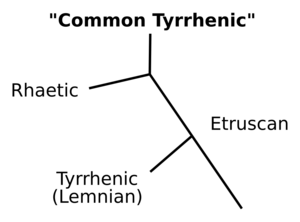

Etruscan Language Family Tree

The Tyrsenian Family: Etruscan's Relatives

In 1998, a scholar named Helmut Rix suggested that Etruscan is part of a language family called Tyrsenian. This family includes other ancient languages that are now extinct, like Raetic, spoken in the eastern Alps, and Lemnian, found on the island of Lemnos. Some experts also think the Camunic language, from the Central Alps, might be related.

Most scholars now agree with the Tyrsenian family idea. They have found similar features in how these languages were structured and sounded, even though we don't have many words from Raetic and Lemnian. The Tyrsenian languages are often considered "Paleo-European." This means they were spoken in Europe before the arrival of the Indo-European languages, which are the ancestors of most modern European languages.

Recent studies of ancient DNA from Etruscan people, who lived between 800 BC and 1 BC, show that the Etruscans were native to Italy. Their genes were similar to those of early Latins. This suggests that the Etruscan language, and the other Tyrsenian languages, might be a very old language family that survived in Europe since the Neolithic period (New Stone Age).

Old Ideas About Etruscan's Origins

For many centuries, figuring out where Etruscan came from was a big puzzle for language experts. It was generally agreed that Etruscan was quite different from other languages in Europe. Before the Tyrsenian family idea became popular, Etruscan was often thought of as a "language isolate," meaning it had no known relatives.

Over time, many different theories about Etruscan were suggested. Some thought it might be related to Ancient Greek, or languages from Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), or even Hebrew or Hungarian. However, most of these ideas have not been accepted by scholars today. The main agreement among experts is that Etruscan is not an Indo-European or Semitic language. Its closest known relatives are Raetic and Lemnian, forming the Tyrsenian family.

How Etruscan Was Written

The Etruscan Alphabet

The Latin script, which we use for English today, actually came from the Etruscan alphabet! The Etruscans got their alphabet from a specific type of Greek alphabet used by Greek settlers in southern Italy. This Greek alphabet itself came from older West Semitic scripts.

The Etruscans recognized an alphabet with 26 letters. We can see an early example of this alphabet carved on a small vase from around 650–600 BC. However, the Etruscans didn't use all 26 letters. For instance, their language didn't have the 'b', 'd', or 'g' sounds, so they didn't use those letters. They also created a new letter for their 'f' sound.

Writing Style and Sounds

Etruscan was usually written from right to left. In very old inscriptions, it sometimes went back and forth, like an ox plowing a field (this is called boustrophedon). At first, words were written continuously, without spaces. Later, from the 6th century BC, dots or colons were used to separate words or even syllables.

Etruscan writing was phonetic, meaning letters represented sounds. However, many inscriptions were shortened, and the letters were sometimes written casually, making them hard to read. Spelling could also change from city to city, probably because people pronounced words differently.

Etruscan speech often put a strong emphasis on the first syllable of a word. This could cause other vowels in the word to become weaker or even disappear, which wasn't always shown in writing. For example, the Greek name Alexandros became Alcsntre in Etruscan. This is one reason why some Etruscan words look like they have "impossible" groups of consonants.

Changes Over Time

The Etruscan writing system had two main periods:

- The archaic phase (7th to 5th centuries BC) used an early Greek alphabet.

- The later phase (4th to 1st centuries BC) changed some of the letters. During this later period, more vowels disappeared from words.

Even after the Etruscan language faded away, its alphabet lived on. It was the source for the Roman alphabet, as well as other alphabets in Italy. Some experts even believe it influenced the Elder Futhark, the oldest form of the runes used by Germanic peoples.

Important Etruscan Discoveries

The study of Etruscan inscriptions is organized in big collections like the Corpus Inscriptionum Etruscarum.

Bilingual Texts: A Rosetta Stone for Etruscan

One of the most exciting finds for understanding Etruscan is the Pyrgi Tablets. These are three gold sheets with a text written in both Etruscan and Phoenician. They date back to around 500 BC. The Phoenician text helped scholars understand some parts of the Etruscan, like the word for 'three', which is ci.

Longer Etruscan Texts

Most Etruscan writings are short, but a few longer ones give us more clues:

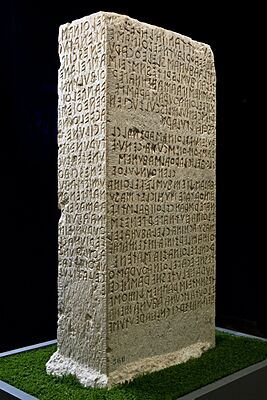

- The Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis: This is the longest Etruscan text, with about 1,200 readable words. It was written on linen and later used to wrap a mummy in Egypt. It seems to be a religious calendar with many prayers.

- The Tabula Capuana: This inscribed clay tile has about 300 words in 62 lines, also appearing to be a religious calendar from the 5th century BC.

- The Cippus Perusinus: This stone slab, found near Perugia, has 46 lines and about 130 words. It likely describes a legal agreement between two Etruscan families about property and water rights.

- The Piacenza Liver: This is a bronze model of a sheep's liver with the names of gods engraved on different sections. It was used for divination.

- The Tabula Cortonensis: A bronze tablet from Cortona with about 200 words, probably a legal contract about land. It helped us learn the Etruscan word for 'lake', tisś.

Inscriptions on Monuments and Objects

Most of what we know about the Etruscans comes from their tombs. These underground chambers were often decorated with paintings and filled with objects. They give us a glimpse into Etruscan life and beliefs. Some famous cemeteries include Caere (modern Cerveteri) and Tarquinia, both UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Etruscan writing is also found on many everyday objects:

- Votive Offerings: These were gifts to the gods, often with short inscriptions.

- Mirrors: Etruscan women used bronze mirrors, called specula. The backs were often decorated with scenes from mythology and had names of the characters written in Etruscan.

- Cistae: These were bronze containers, like baskets, used by women to store small items. They were beautifully decorated with mythological scenes and sometimes had inscriptions.

- Rings and Ringstones: Finely engraved gemstones set in gold rings often depicted mythological figures with Etruscan names.

- Coins: Etruscan coins, made of gold, silver, and bronze, were minted between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC. They often had the name of the city that made them and images of gods or mythical creatures.

Etruscan Grammar Basics

Etruscan was an agglutinative language. This means it built words by adding many suffixes, one after another, to a base word. Think of it like adding LEGO bricks to build a longer structure.

Nouns and Pronouns

Etruscan nouns had different endings depending on their role in a sentence (like subject, object, or showing possession). They also had singular and plural forms. Unlike many languages, Etruscan nouns didn't usually have a gender (masculine or feminine), except for in personal names and pronouns.

For example, if Latin might have a completely different word for "sons" and "to the sons," Etruscan would add an ending for "plural" and then another ending for "to the."

Personal pronouns included mi ('I') and mini ('me'). There were also pronouns for 'he/she/they' (an) and 'it' (in). Demonstrative pronouns, like ca and ta, were used for 'this' or 'that'.

Verbs and How They Change

Etruscan verbs also changed their endings.

- For the present tense, verbs often used a simple root word or added an -a.

- For the past tense, a suffix like -(a)ce was added. So, tur ('gives') became tur-ce ('gave').

- There were also ways to give commands, like tur ('dedicate!'). Interestingly, some anti-theft inscriptions on objects used the command capi ('take' or 'steal') to warn people not to take them!

Etruscan Words We Know

We only understand a few hundred Etruscan words for sure. Some words were borrowed from Etruscan into Latin, and then into other languages. For example, the Latin word familia (family) might have come from Etruscan. Other words like vulture and trumpet may also have Etruscan roots.

Etruscan Numbers

There's been a lot of discussion about whether Etruscan numbers are related to Indo-European numbers. However, most experts agree that Etruscan numbers are not Indo-European.

Here are some of the lower Etruscan numbers:

| Value | Etruscan Word |

|---|---|

| 1 | θu or tun |

| 2 | zal |

| 3 | ci |

| 4 | śa or huθ |

| 5 | maχ |

| 6 | huθ or śa |

| 7 | śemφ |

| 8 | *cezp |

| 9 | nurφ- |

| 10 | śar or zar |

It's a bit tricky because some numbers, like 4 and 6, might have had two different words, or the words for 7, 8, and 9 are still being figured out. Also, śar could mean 10 or 12, depending on the system used.

For larger numbers, zaθrum was 20, cealχ was 30, and śran was 100.

Everyday Etruscan Words

Here are some other Etruscan words that scholars have identified:

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

In Spanish: Idioma etrusco para niños

In Spanish: Idioma etrusco para niños