Antonio Gramsci facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Antonio Gramsci

|

|

|---|---|

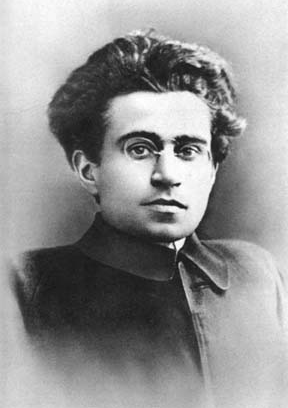

Gramsci in 1916

|

|

| Born |

Antonio Francesco Gramsci

22 January 1891 Ales, Sardinia, Italy

|

| Died | 27 April 1937 (aged 46) Rome, Italy

|

| Alma mater | University of Turin |

|

Notable work

|

Prison Notebooks |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Secretary of the Communist Party of Italy | |

| In office 14 August 1924 – 8 November 1926 |

|

| Preceded by | Amadeo Bordiga |

| Succeeded by | Palmiro Togliatti |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Italian Communist Party |

| Signature | |

Antonio Francesco Gramsci (born January 22, 1891 – died April 27, 1937) was an important Italian thinker, writer, and politician. He was a Marxist philosopher, a journalist, and a linguist. He wrote about philosophy, politics, sociology, history, and linguistics.

Gramsci was one of the people who helped start the Italian Communist Party and even led it for a time. He was a strong critic of Benito Mussolini and his fascism movement. Because of his political views, Gramsci was put in prison in 1926 and stayed there until he died in 1937.

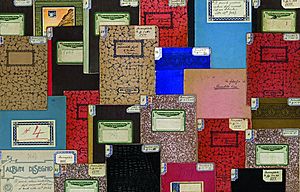

While in prison, Gramsci wrote more than 30 notebooks, filling over 3,000 pages with his thoughts and ideas. These writings, known as his Prison Notebooks, are very important for understanding 20th-century political ideas. Gramsci got ideas from many different thinkers, not just other Marxists. He looked at the works of people like Niccolò Machiavelli, Vilfredo Pareto, Georges Sorel, and Benedetto Croce. His notebooks cover many topics, including Italian history, nationalism, the French Revolution, fascism, factory work methods like Fordism, civil society, folklore, religion, and different types of culture.

Gramsci is most famous for his idea of cultural hegemony. This idea explains how the government and the powerful ruling class (called the bourgeoisie) use cultural things like schools, media, and traditions to keep their power in a capitalist society. Gramsci believed that this ruling class spreads its own values and ideas so that they become the "common sense" for everyone. This way, people agree to the capitalist system without needing to be forced. This "cultural hegemony" helps keep society stable and prevents big changes.

Gramsci also wanted to move away from the idea that everything in society is only about money and economics, which was a common view in traditional Marxist thought. Because of this, he is sometimes called a neo-Marxist. He saw Marxism as a way of thinking that focuses on human actions and history, rather than just on material things.

Contents

Life Story

Growing Up

Gramsci was born in Ales, on the island of Sardinia, Italy. He was the fourth of seven sons. His father had financial difficulties and problems with the law, which meant the family had to move often. They finally settled in Ghilarza.

When Antonio was seven, his father was imprisoned. This made his family very poor. Young Antonio had to stop school and work odd jobs to help his family until his father was released in 1904.

Gramsci had health problems from a young age. He had a spinal condition that made him shorter than five feet and caused a hunchback. For a long time, people thought this was from an accident, but it might have been from a type of tuberculosis that affects the spine. He also had other health issues throughout his life.

He started secondary school in Santu Lussurgiu and finished in Cagliari. There, he lived with his older brother Gennaro, who was a strong socialist. At first, Antonio was more interested in the problems of poor Sardinian farmers and miners. They felt ignored by the richer, industrial North of Italy. This feeling of unfairness helped shape Gramsci's ideas later on.

Life in Turin

In 1911, Gramsci won a scholarship to study at the University of Turin. Turin was a busy industrial city with big factories like Fiat and Lancia. Many workers from poorer areas moved there for jobs. Trade unions were growing, and there were early conflicts between workers and factory owners.

Gramsci studied literature and was very interested in linguistics. He also spent time with socialist groups and Sardinian people who had moved to the mainland. Both his experiences in Sardinia and his new life in Turin influenced his way of thinking. In 1913, he joined the Italian Socialist Party.

Even though he was good at his studies, Gramsci had money problems and poor health. These issues, along with his growing interest in politics, led him to leave university in 1915, when he was 24. By then, he had learned a lot about history and philosophy.

From 1914, Gramsci started writing for socialist newspapers. His articles for Il Grido del Popolo (The Cry of the People) made him known as a talented journalist. In 1916, he became a co-editor of Avanti!, the official newspaper of the Socialist Party. He wrote a lot about social and political events in Turin.

Gramsci also worked to educate and organize workers in Turin. He gave his first public speech in 1916 and talked about topics like the French Revolution and the Paris Commune. After some socialist leaders were arrested in 1917, Gramsci became one of Turin's main socialist figures. He was elected to the party's committee and became editor of Il Grido del Popolo.

In April 1919, Gramsci and some friends started a weekly newspaper called L'Ordine Nuovo (The New Order). This group supported the idea of workers' councils, which were groups of workers who wanted to take control of how factories were run. Gramsci believed these councils were important for workers to gain power.

Joining the Communist Party

Gramsci became convinced that a strong Communist Party was needed in Italy. On January 21, 1921, the Italian Communist Party (PCd'I) was founded in Livorno. Gramsci was a leader from the start. He also supported the Arditi del Popolo, a group that fought against the Blackshirts, who were Mussolini's supporters.

In 1922, Gramsci went to Russia to represent the new party. There, he met Julia Schucht, a violinist. They married in 1923 and had two sons, Delio and Giuliano. Gramsci never saw his second son.

While Gramsci was in Russia, fascism was growing stronger in Italy. He returned with the goal of uniting different leftist parties to fight against fascism.

In late 1922 and early 1923, Mussolini's government began arresting many opposition leaders, including some from Gramsci's party. Gramsci then traveled to Vienna to help rebuild the party.

In 1924, Gramsci became the head of the PCd'I and was elected as a deputy (a type of politician) for the Veneto region. He started the party's official newspaper, L'Unità (Unity). In 1926, the party adopted Gramsci's ideas for uniting against fascism and bringing back democracy to Italy.

Imprisonment and Death

On November 9, 1926, the Fascist government passed new strict laws. The police arrested Gramsci, even though he had parliamentary immunity (which usually protects politicians from arrest). He was taken to the Regina Coeli prison in Rome.

At his trial, the prosecutor famously said, "For twenty years we must stop this brain from functioning." Gramsci was first sentenced to five years on the island of Ustica, and then to 20 years in prison in Turi.

During his 11 years in prison, Gramsci's health got much worse. He suffered from many illnesses, including problems with his digestion and severe headaches.

People around the world campaigned for his release. In 1933, he was moved to a clinic, but he still didn't get proper medical care. Two years later, he was moved to another clinic in Rome. He was supposed to be released on April 21, 1937, and planned to go to Sardinia to recover. However, he was too ill to move.

Antonio Gramsci died on April 27, 1937, at 46 years old. His ashes are buried in the Cimitero Acattolico in Rome. His death was directly linked to the harsh conditions he faced in prison.

Gramsci's Ideas

Gramsci was one of the most important Marxist thinkers of the 20th century. His Prison Notebooks contain many of his key ideas, such as:

- Cultural hegemony: How the ruling class uses culture to keep power.

- Workers' education: The idea that working-class people need good education to develop their own thinkers.

- The State and Civil Society: How the government (political society) uses force, and how groups like families and schools (civil society) get people to agree to the system.

- Historicism: The belief that all ideas and meanings come from human actions and history.

- Critique of "economism": His argument that society is not just shaped by economic changes, but also by culture and human will.

Cultural Hegemony Explained

The idea of hegemony was used by earlier Marxists to describe the working class leading a revolution. Gramsci expanded this idea greatly. He looked closely at how the ruling capitalist class (the bourgeoisie) keeps control.

Traditional Marxism predicted that a socialist revolution would definitely happen in capitalist countries. But by the early 1900s, this hadn't happened in many advanced nations. Gramsci suggested that capitalism stayed strong not just through force or money, but also through ideology (a set of beliefs). The ruling class created a dominant culture that spread its values and rules, making them seem like "common sense" to everyone. This made people, even those in the working class, believe that what was good for the ruling class was good for everyone. This helped keep things the same instead of leading to a revolution.

To challenge this, Gramsci believed the working class needed to create its own culture. He thought that gaining cultural power was key to gaining political power. For Gramsci, a class can't rule just by looking out for its own money interests or by using force. It must also lead with ideas and morals, and make alliances with different groups. He called this combination of social forces a "historic bloc." This bloc helps people agree to a certain social order, and the ruling class keeps its power through institutions, relationships, and ideas.

Gramsci believed that the ruling class's cultural values were connected to folklore, popular culture, and religion. He was also impressed by the Catholic Church's influence and how it kept the religion of educated people and less educated people from becoming too different. Gramsci thought that Marxism could only replace religion if it met people's spiritual needs and felt like it came from their own experiences.

Thinkers and Education

Gramsci thought a lot about the role of intellectuals (people who think deeply and share ideas) in society. He said that everyone has the ability to think, but not everyone has the job of being an intellectual. He saw modern intellectuals as practical leaders and organizers who spread the ruling ideas through things like education and media.

He also made a difference between "traditional" intellectuals, who think they are separate from society, and "organic" intellectuals. "Organic" intellectuals come from a specific social class and help that class express its feelings and experiences. For Gramsci, it was the job of these organic intellectuals to explain the hidden wisdom or "common sense" of their own social groups. These intellectuals would represent groups that were often left out of society.

Gramsci believed that to challenge capitalist power, a "counter-hegemony" was needed. This meant that working-class intellectuals and others needed to create different values and ideas that went against the ruling class's ideas. He argued that this was necessary for a successful revolution in advanced capitalist societies.

This idea of creating a working-class culture and a counter-hegemony is linked to Gramsci's call for a type of education that could help working-class people become intellectuals. Their job was not to just teach Marxist ideas, but to help people think critically about the way things were. His ideas about education are similar to what is now called critical pedagogy and popular education, which are still important for adult education today.

The State and Society

Gramsci's idea of hegemony is connected to how he saw the capitalist state. He didn't just see the state as the government. Instead, he divided it into:

- Political society: This includes the police, army, and legal system, which use force and laws to control.

- Civil society: This includes families, schools, and trade unions. These are seen as private groups that connect the government and the economy.

Gramsci said that the capitalist state rules through both force and agreement. Political society uses force, and civil society gets people's agreement.

He suggested that under modern capitalism, the ruling class can keep its economic power by meeting some demands from trade unions and political parties within civil society. This way, the ruling class makes small changes to keep its power, which Gramsci called a "passive revolution." He saw things like reformism (making gradual changes) and fascism, as well as modern factory methods like those of Frederick Taylor and Henry Ford, as examples of this.

Gramsci believed that the "Modern Prince" – meaning the revolutionary party – would help the working class develop its own intellectuals and create a different kind of power within civil society. He thought that because modern civil society is so complex, a "war of position" (a long struggle through political action, unions, and culture) was needed before a direct revolution (a "war of manoeuvre") could succeed without leading to problems.

Influence

Gramsci's ideas started within the political left, but they have also become very important in academic discussions about cultural studies and critical theory. Even political thinkers from the center and right have found his ideas useful. His concept of hegemony, for example, is often talked about. His work has especially influenced modern political science (see Neo-Gramscianism). He also greatly influenced discussions about popular culture, where many see the potential for people to resist powerful government and business interests.

Some critics say that Gramsci's ideas encourage a struggle for power through ideas. They argue that his approach to thinking about philosophy goes against open, liberal ways of studying ideas that are not political.

Gramsci's legacy as a socialist has been debated. After World War II, Palmiro Togliatti, who led the Italian Communist Party, claimed that the party's actions followed Gramsci's ideas. However, some believe that Gramsci might have been removed from his party if his true views, especially his growing dislike for Stalin, had been known.

A recent book about Gramsci suggests that he made a mistake in how he fought fascism in parliament. Gramsci was elected to parliament and gave only one speech in 1925 before he was arrested. In that speech, he defended the use of violence by the left, saying it was better than fascist violence because the left represented the majority. However, the book argues that Gramsci would have been more effective if he had spoken out against violence from all sides and argued for the rule of law and a fair legal system. He could have started by condemning the murder of Giacomo Matteotti, a politician who had called for the rule of law and was murdered by fascists. That murder caused a crisis for the fascist government that Gramsci could have used. The book also suggests that Gramsci and other socialists were too trusting and didn't realize how brutal the fascist government could be.

See also

In Spanish: Antonio Gramsci para niños

In Spanish: Antonio Gramsci para niños

- Subaltern Studies

- Subaltern (postcolonialism)

- Reformism

- Articulation (sociology)

- Risorgimento

- Praxis School

- Liberation theology

- Antonio Gramsci Battalion

Images for kids

-

Former Gymnasium Carta-Meloni in Santu Lussurgiu where Antonio Gramsci went 1905–1907

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |