Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (triumvir) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

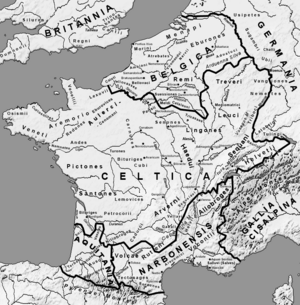

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

|

|

|---|---|

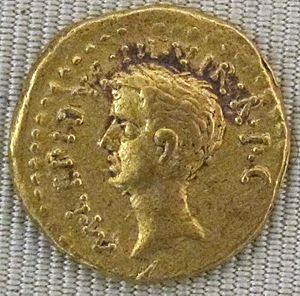

Denarius depicting Lepidus. The inscription is III vir rei publicae c(onstituendae) Lepidus pont(ifex) max(imus), meaning "triumvir for the regulation of the republic, Lepidus, chief pontiff".

|

|

| Born | c. 89 BC |

| Died | 13 BC (aged c. 76) Circeii, Roman Empire

|

| Nationality | Roman |

| Office | Interrex (52 BC) Praetor (49-47 BC) Propraetor (47-46 BC) Magister Equitum (46-44 BC) Consul (46, 42 BC) Triumvir (43–36 BC) Pontifex Maximus (44-13/12 BC) Proconsul (43-40 and 38-36 BC) |

| Spouse(s) | Junia Secunda |

| Children | Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Minor Quintus Aemilius Lepidus Aemilia Lepida (possibly) |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Military service | |

| Years of service | 48–36 BC |

| Battles/wars |

|

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (born around 89 BC – died in 13 or 12 BC) was an important Roman general and politician. He was part of the Second Triumvirate, a powerful group of three leaders who ruled Rome during the final years of the Roman Republic. The other two members were Octavian and Mark Antony.

Before joining the Triumvirate, Lepidus was a close friend and supporter of Julius Caesar. He also held the important religious title of pontifex maximus, which was the chief priest of Rome. Even though he was a skilled military leader, Lepidus is often seen as the least powerful member of the Triumvirate.

Contents

Family Background

Lepidus was the son of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who was a consul (a top Roman official) in 78 BC. His father led a rebellion that failed.

Lepidus married Junia Secunda. She was the half-sister of Marcus Junius Brutus, one of the leaders who assassinated Julius Caesar. Lepidus and Junia Secunda had at least one son, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus the Younger.

Life and Career

Becoming an Ally of Caesar

Lepidus joined the College of Pontiffs (a group of priests) when he was a child. He started his political career by overseeing the minting of coins. Soon, he became one of Julius Caesar's strongest supporters.

In 49 BC, Lepidus was made a praetor, a high-ranking judge. He was put in charge of Rome while Caesar was away fighting Pompey in Greece. Lepidus helped Caesar become dictator, a very powerful position.

As a reward, Lepidus was made governor of the Spanish province of Hispania Citerior. While there, he helped calm a rebellion by negotiating with the rebels and defeating an attack. Caesar and the Senate were so impressed that they gave him a special parade called a Roman triumph.

Rising to Power

Lepidus became a consul in 46 BC, after Caesar defeated his enemies. Caesar also made Lepidus his "Master of the Horse", which meant he was Caesar's second-in-command. Caesar trusted Lepidus to keep order in Rome more than he trusted Mark Antony.

In February 44 BC, Caesar was made dictator for life. He again appointed Lepidus as his Master of the Horse. However, this powerful partnership ended suddenly when Caesar was assassinated on March 15, 44 BC. Caesar had actually eaten dinner at Lepidus's house the night before he was murdered.

After Caesar's Death

When Lepidus heard about Caesar's murder, he quickly moved his troops to keep order in Rome. He wanted to punish Caesar's killers, but Mark Antony convinced him not to. Lepidus and Antony agreed to an amnesty for the assassins. Lepidus also took over Caesar's important role as pontifex maximus.

At this time, Sextus Pompey, the son of Caesar's old enemy, tried to take control of Spain. Lepidus was sent to deal with him. Lepidus successfully negotiated a peace agreement with Sextus. The Senate praised Lepidus for this. He then governed both Hispania and Narbonese Gaul.

Later, when Mark Antony tried to take control of northern Italy, the Senate asked Lepidus to fight against him. Lepidus tried to negotiate instead. When Antony's army met Lepidus's, many of Lepidus's soldiers joined Antony. Lepidus then made an agreement with Antony. It's not clear if his troops forced him to join Antony, or if it was his plan all along.

Forming the Second Triumvirate

Antony and Lepidus then had to deal with Octavian Caesar, Caesar's adopted son. Octavian was the only leader left from the forces that had defeated Antony. The three men – Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian – met and formed the Second Triumvirate. This was a formal agreement to share power, unlike earlier informal alliances.

The Triumvirate was officially recognized by Roman law for five years. This group basically took over from the consuls and the Senate, marking the end of the Roman Republic. Lepidus was given control of Spain and Narbonese Gaul. However, he agreed to give seven of his legions (large army units) to Octavian and Antony to fight against Caesar's assassins, Brutus and Cassius, who controlled the eastern parts of the Roman territory. Lepidus was also made consul and confirmed as Pontifex Maximus. He was to manage Rome while the others were away.

Giving up his legions meant Lepidus would have a less powerful role in the Triumvirate. He also agreed to remove political opponents of Caesar's group.

After the Battle of Philippi

After Brutus and Cassius were defeated in the Battle of Philippi, Antony and Octavian took most of Lepidus's territories. However, they gave him control of the provinces of Numidia and Africa. For a while, Lepidus stayed out of the arguments between Antony and Octavian.

When a war broke out in 41 BC, Octavian asked Lepidus to defend Rome. Lepidus was later given six of Antony's legions to govern Africa. In 37 BC, the Triumvirate was renewed for another five years.

While governing Africa, Lepidus helped give land to Roman soldiers who had retired. He also encouraged Roman culture in the area.

Losing Power

In 36 BC, during a revolt in Sicily led by Sextus Pompey, Lepidus gathered a large army of 14 legions to help defeat him. However, this led to a mistake that Octavian used to remove Lepidus from power.

After Sextus Pompey was defeated, Lepidus's legions were in Sicily. A disagreement started about who had authority over the island – Lepidus or Octavian. Lepidus felt he was being treated unfairly and demanded that Sicily be part of his territory. He even suggested a trade: Octavian could have Sicily and Africa if Lepidus got back his old territories in Spain and Gaul.

Octavian accused Lepidus of trying to take too much power and starting a rebellion. Lepidus's legions in Sicily then switched their loyalty to Octavian. Lepidus was forced to surrender to Octavian.

On September 22, 36 BC, Lepidus was stripped of all his official positions except for Pontifex Maximus. Octavian then sent him to live in Circeii. Later, Lepidus's son was involved in a plot to kill Octavian and was executed. However, Lepidus himself was left alone.

Lepidus lived the rest of his life quietly. He died peacefully in late 13 BC. After his death, Octavian (who was now called "Augustus") was elected to the position of Pontifex Maximus.

Reputation and Legacy

Historians, both ancient and modern, have often described Lepidus as "weak, indecisive, and disloyal." For example, the Roman writer Cicero criticized Lepidus for letting his forces join Mark Antony. Another writer called him "the most fickle of mankind." Even Shakespeare shows Lepidus as a less important character in his play Julius Caesar.

However, some modern historians argue that these views might be unfair. They suggest that the information we have about Lepidus was often written by his political enemies, like Cicero and Augustus. These historians believe that Lepidus's actions were often logical and that he was no more disloyal than other powerful figures of his time. They argue that his attempt to gain more power in Sicily was a reasonable move to regain his position.

See also

In Spanish: Lépido para niños

In Spanish: Lépido para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |