History of Naples facts for kids

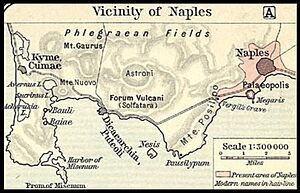

The history of Naples is very old and interesting, going back to when Greek people first settled in the area around 2000 BC. Towards the end of the Greek Dark Ages, a larger Greek settlement called Parthenope started on the Pizzofalcone hill in the 8th century BC. It was later rebuilt as Neapolis (meaning "New City") in the 6th century BC and became a very important city in Magna Graecia, which was the name for the Greek areas in southern Italy.

Naples' Greek culture was very important to the later Roman society. When the city became part of the Roman Republic and then the Roman Empire, it remained a major cultural center.

Over time, Naples was the capital of several kingdoms, including the Duchy of Naples (661–1139), the Kingdom of Sicily, the Kingdom of Naples (1282–1816), and finally the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies until Italy became one country in 1861. Many different civilizations and cultures have shaped Naples, leaving their mark on its art and buildings. During the Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment, it was a big center for culture. It was also a key city for the Baroque art style, especially after the artist Caravaggio started his career there in the 1600s.

During the Neapolitan War, the people of Naples rebelled against their rulers, the Bourbon family. This rebellion helped start the movement for Italy to become a single country.

Today, Naples is part of the Italian Republic. It's the third largest city in Italy by population, after Rome and Milan.

Contents

Early Beginnings of Naples

The very first signs of people living in the Naples area go back to the Middle Neolithic period (New Stone Age). Scientists found traces of an ancient culture near the Santa Maria degli Angeli a Pizzofalcone church. There were also signs of people from the Copper Age and early/middle Bronze Age in the same area.

Evidence of the Gaudo culture was found in ancient tombs in Materdei.

Near the Pizzofalcone hill, close to the Port of Naples, archaeologists found pottery from the late Bronze Age to the early Iron Age. This suggests that people were active in coastal activities there, likely making things.

Around 2000 BC, a very early settlement from the Mycenaean civilization (an ancient Greek civilization) was built close to where the city of Parthenope would later be.

Greek and Roman Times

Parthenope, the First City

The city of Parthenope was founded by people from Cumae, which was the first Greek city on mainland Italy, in the late 8th century BC. Parthenope was named after a siren from Greek myths. The story says she washed ashore at Megaride after failing to charm Ulysses with her singing. The settlement was built on the Pizzofalcone promontory, which was a good spot to control sea traffic.

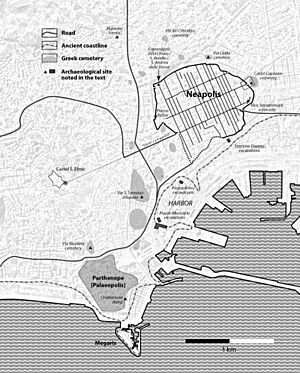

Not many ancient remains of Parthenope have been found, but a burial ground from the 7th century BC was discovered in Via Nicotera. A pile of discarded pottery from the Archaic Age was found in Via Chiatamone, which had slid down from Pizzofalcone hill. A wall made of tuff (a type of rock) from the 6th century BC was found near the town hall. This wall was part of the port and might have been used for defense or as a boundary.

When more people started visiting the colony because it was a pleasant place, the people of Cumae worried their own city would be abandoned. So, they decided to "destroy" Parthenope.

Neapolis: The New City

Neapolis, meaning "New City," was founded by wealthy families from Cumae who were forced out by a ruler named Aristodemus of Cumae after a battle in 507 BC.

These families wanted Neapolis to be a "second Cumae," similar to their old city. For example, they continued to worship gods like Demeter and kept the same social structure. Archaeological discoveries support this timeline.

The original settlement of Parthenope on Pizzofalcone hill was then called Palaipolis (meaning "old city"). It continued to exist as a smaller, older part of Neapolis.

The new city was planned with a grid of straight streets. It was built on a flat area that sloped from north to south, providing space for the new city. Swamps made it hard to travel inland, so Neapolis couldn't have large farms like other parts of Campania. This meant Neapolis focused on the sea and trade to survive.

The city eventually became one of the most important cities in Magna Graecia. It kept its Greek culture for a long time, even after being defeated by the Romans.

Neapolis had an acropolis (a fortified high part of the city), an agora (a public meeting place), and burial grounds. It also had strong walls built in the 5th century, an odeon (a small theater), a larger theatre, and a temple for its patron gods, the Dioscuri.

Influence from Athens and Syracuse

Neapolis soon became more important than Cumae in sea trade. It took control of the sea route from the Cumaean gulf to the Neapolitan gulf. This success happened because the rulers of Syracuse (another powerful Greek city) became weaker around 466 BC. Also, the Syracusan soldiers left Pithecusae (Ischia) due to a strong earthquake or volcanic eruption. Neapolis quickly took over Ischia, showing the competition between the cities.

The Athenians (from Athens, Greece) soon created a network of trade routes in the Tyrrhenian Sea. They were interested in Campania, Sicily, and the Adriatic Sea because they needed food, especially grains, for their growing population. Athens' presence brought many changes to Naples: the port area grew a lot, and Naples formed closer ties with farming areas that grew wheat.

However, Syracuse tried to control the Tyrrhenian Sea, which was a problem for Athens and Naples. In 413 BC, Athens' attack on Syracuse during the Peloponnesian War failed badly. This, along with a plague, weakened Athens' economy, and its relationship with Neapolis became less strong.

The Samnites Arrive

At the end of the 5th century BC, the Samnites, a tribe speaking the Oscan language, became a big threat to Neapolis. They were expanding into the more fertile plains.

In 423 BC, Capua, a large Etruscan city, was conquered by the Samnites. The Oscan-speaking people there gained more freedom. In 421 BC, Cumae also fell after a difficult siege. Many people fleeing Cumae found safety within the walls of Neapolis, which helped them because Cumae had founded Neapolis. Neapolis managed to stay safe by allowing Samnite leaders to hold important public jobs in the city. However, this damaged its relationship with Cumae.

In the second half of the 4th century BC, during the First Samnite War, Neapolis joined the Samnites against Rome, which had already taken Capua.

In 327 BC, the Second Samnite War started because of tensions caused by Rome's actions in Campania and partly by Neapolis. Although the historian Livy might have been biased, he said that Neapolis attacked Romans living in Campania. After Rome's request for compensation was refused, Neapolis declared war, and two Roman armies marched into Campania.

In 326 BC, after destroying the countryside, the Roman army led by Quintus Publilius Philo marched on Neapolis and surrounded it. About four thousand Samnite and Nolan soldiers arrived to defend Neapolis. The Romans set up camp between the old and new cities. After a year-long siege, some Greek citizens betrayed the city, leading to its surrender to the Romans. However, Rome allowed Neapolis to keep much of its independence, its customs, language, and Greek traditions. Rome preferred to make a special agreement called foedus Neapolitanum, recognizing Naples' important role as a port city.

Roman Times

In 280 BC, after the Battle of Heraclea, Pyrrhus of Epirus realized he couldn't make a deal with the Romans. He attacked, moving his army north. He went to Neapolis, hoping to capture it or make it rebel against Rome. This failed attempt wasted time, which helped the Romans. When he reached Capua, he found it already guarded by Roman soldiers.

In 211 BC, during the Second Punic War, Capua was severely punished by the Romans for siding with Hannibal. This led to Neapolis becoming more important in Campania.

From 199 BC, Naples' role as a sea power began to shrink, as its nearby rival Puteoli grew. When Neapolis became a Roman municipium (a Roman town with some self-governance), it lost some of its independence, though its Greek-style administration continued.

Neapolis supported Gaius Marius the Younger in the civil war of 82 BC. As a result, it was badly damaged by the armies of his opponent, Sulla. The war took away Naples' fleet and the island of Ischia, hurting its trade. However, the city still served as a regional port, as shown by many archaeological finds in Piazza del Municipio.

Then, in 50 BC, the city supported Pompey in the Civil War against Julius Caesar. Again, choosing the losing side meant the city's economy declined. Misenum became the main naval base on the Tyrrhenian Sea, and even Baiae became a strong competitor for tourism and thermal baths.

Under Emperor Augustus, the city began to recover. It became a thriving center of Hellenistic (Greek-influenced) culture, attracting Romans who wanted to improve their knowledge of Greek culture. The Neapolitan Isolympic Games, or Sebasta, were started by Augustus in 2 AD. They were like the games at Olympia and became one of the most important games in the western Roman Empire. As archaeologist Amedeo Maiuri said:

- Naples was the only city in the Western Roman world to host games in honor of Augustus. This was not so much because of the Emperor's personal influence or for any political reason, but more because of the city's Greek culture. In fact, while Greek culture was declining in other parts of southern Italy and Sicily, Neapolis was still using the Greek language, its own systems, religious practices, and customs. Because of this, Neapolis could be seen as the main city for Greek culture in the Western Roman Empire during its early period.

These games were held every five years and attracted competitors from all over the empire. Augustus himself attended in 14 AD.

Naples' pleasant climate made it a famous resort. Many luxurious villas were built along the coast from the Gulf of Pozzuoli to the Sorrentine peninsula. Lucullus built a huge villa estate here, covering much of what would become the later city. The famous area of Posillipo gets its name from the ruins of Villa Pausílypon, which in Greek means "a pause, or rest, from worry." Romans connected the city to the rest of Italy with their famous roads, dug tunnels to link Naples to Pozzuoli, made the port bigger, and added public baths and aqueducts to improve life in Naples. The city was also known for its many festivals and shows.

More problems came with earthquakes in 62 and 64 AD and the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD.

According to stories, the saints Peter and Paul came to the city to preach. Christians became very important in the later years of the Roman Empire. There are several notable catacombs (underground burial places), especially in the northern part of the city. The first early Christian churches were built near the entrances to these catacombs. The very popular patron saint of the city, San Gennaro (St. Januarius), was beheaded in nearby Pozzuoli in 305 AD. Since the 5th century, he has been remembered by the basilica of San Gennaro extra Moenia. The Cathedral of Naples is also dedicated to St. Gennaro.

It was in Naples, at Lucullus's villa (now the Castel dell'Ovo), that Romulus Augustulus, the last official emperor of the Western Roman Empire, was sent into exile after being removed from power in 476 AD.

Naples suffered a lot during the Gothic War (535–552) between the Ostrogoths and the Byzantines. In 536, it was guarded by Goths and decided to fight against the Byzantine commander Belisarius's invasion. However, in the Siege of Naples (536), his troops captured the city by entering through its aqueduct. As the war changed in the 540s, the Ostrogoth leader Totila starved the city into surrendering, but then treated it kindly. During Narses's expedition in the 550s, the Empire captured it again. When the Lombards invaded and conquered much of Italy in the following years, Naples remained loyal to the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Duchy of Naples

When the Lombards invaded, Naples had about 30,000-35,000 people. In 615, under Giovanni Consino, Naples rebelled for the first time against the Exarch of Ravenna, who was the emperor's representative in Italy. In response, the first form of a duchy was created in 638. However, this duke came from outside and had to report to the general of Sicily. At that time, the Duchy of Naples controlled an area similar to today's Province of Naples, including Vesuvius, the Campi Flegrei, the Sorrentine peninsula, and the islands of Ischia and Procida.

In 661, with the emperor's permission, Naples was ruled by a local duke, Basil of Naples. His loyalty to the emperor soon became only in name. In 763, Duke Stephen II changed his loyalty from Constantinople to the Pope. In 840, Duke Sergius I made the duchy hereditary, meaning it would be passed down in his family. From then on, Naples was truly independent. At this time, the city was mainly a military center, ruled by a group of warriors and landowners. Naples was not a big trading city like other sea cities in Campania, such as Amalfi and Gaeta, but it had a good fleet that fought in the Battle of Ostia against the Saracens in 849. Naples even allied with non-Christians if it helped them. For example, in 836, Naples asked for help from the Saracens to fight off a siege by Lombard troops from the nearby Duchy of Benevento. Later, Muhammad I Abu 'l-Abbas led a Muslim conquest of Naples, sacking it and taking much of its wealth.

After Neapolitan dukes became powerful under Duke-Bishop Athanasius and his successors (like Gregory IV and John II, who fought in the Battle of the Garigliano in 915), Naples became less important in the 10th century until it was captured by its old rival, Pandulf IV of Capua.

In 1027, Duke Sergius IV gave the county of Aversa to a group of Norman mercenaries led by Rainulf Drengot. He needed their help in a war with the principality of Capua. At that time, he couldn't imagine the consequences, but this act started a process that eventually ended Naples' independence.

The last ruler of these independent southern Italian states, Sergius VII, was forced to surrender to Roger II of Sicily in 1137. Roger had declared himself king of Sicily seven years earlier. Under the new rulers, the city was managed by a compalazzo (palatine count), and the noble families of Naples had very little independence left. During this time, Naples had about 30,000 people and was supported by its lands inland. Trade was mostly done by foreigners, mainly from Pisa and Genoa.

Besides the church of San Giovanni a Mare, Norman buildings in Naples were mostly non-religious, like castles (Castel Capuano and Castel dell'Ovo), walls, and fortified gates.

Normans, Hohenstaufen, and Anjou Rule

After a period of Norman rule, in 1189, the Kingdom of Sicily had a disagreement over who should rule. It was between Tancred, King of Sicily, who was born outside of marriage, and the House of Hohenstaufen, a German royal family. This was because Prince Henry of the Hohenstaufen family had married Princess Constance, the last rightful heir to the Sicilian throne. In 1191, Henry invaded Sicily after being crowned Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor. Many cities surrendered, but Naples fought back from May to August under the leadership of Richard, Count of Acerra, Nicholas of Ajello, Aligerno Cottone, and Margaritus of Brindisi. The Germans then suffered from disease and had to retreat. Conrad II, Duke of Bohemia and Philip I, Archbishop of Cologne died from illness during the siege. Because of this, Tancred achieved another unexpected success: his rival Constance, now empress, was captured at Salerno, while the cities that had surrendered to the Germans returned to Tancred's side. Tancred had the empress imprisoned at Castel dell'Ovo in Naples before she was released in May 1192. In 1194, Henry started his second campaign after Tancred's death. This time, Aligerno surrendered without fighting, and Henry finally conquered Sicily, bringing it under the rule of the Hohenstaufens.

Frederick II Hohenstaufen founded the university in Naples in 1224. He saw Naples as his intellectual capital, while Palermo remained the political center. This university was the only one in southern Italy for seven centuries. After Frederick's son, Manfred, was defeated in 1266, Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily were given by Pope Clement IV to Charles of Anjou. Charles moved the capital from Palermo to Naples. He lived in his new home, the Castel Nuovo, and a new area with palaces and noble homes grew up around it. During Charles's rule, new Gothic churches were also built, including Santa Chiara, San Lorenzo Maggiore, and the Cathedral of Naples.

After the Sicilian Vespers (a rebellion in 1284), the kingdom was split into two parts. An Aragonese king ruled the island of Sicily, and the Angevin king ruled the mainland part. Both kingdoms officially called themselves the Kingdom of Sicily, but the mainland part was usually called the Kingdom of Naples. The Hungarian Angevin king Louis the Great captured the city several times. Even though the kingdom was divided, Naples grew in importance. Merchants from Pisa and Genoa were joined by bankers from Tuscany, and with them came famous artists like Boccaccio, Petrarch, and Giotto.

The Aragonese Period

In 1442, Alfonso I conquered Naples after defeating the last Angevin king, Rene. He made a grand entry into the city in February 1443. The new ruling family helped trade by connecting Naples to the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). They also made Naples a center of the Italian Renaissance. Artists who worked in Naples during this time included Francesco Laurana, Antonello da Messina, Jacopo Sannazzaro, and Angelo Poliziano. The royal court also gave land to nobles in the provinces, but this caused the kingdom to become less unified.

After a short conquest by Charles VIII of France in 1495, the two kingdoms were united under Aragonese rule in 1501. In 1502, the Castilian general Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba entered the city. Although Fernández de Córdoba was Castilian, he conquered under the command of Ferdinand II of Aragon. Ferdinand and his wife Isabella I of Castile ruled their kingdoms together during their marriage. But their partnership ended with Isabella's death in 1504, and Ferdinand removed Castilians from leadership in Aragonese lands in Italy, including Naples. This conquest began almost two centuries of rule by powerful viceré ("viceroys") in Naples.

Under the viceroys, Naples grew from 100,000 to 300,000 people, becoming the second largest city in Europe after Istanbul. The most important viceroy was don Pedro Álvarez de Toledo. He introduced high taxes and supported the Inquisition (a religious court), but he also improved Naples. He opened the main street, which is still named after him today. He paved other roads, made the walls stronger and bigger, repaired old buildings, and built new ones and fortresses. By 1560, he had made Naples the largest and best-fortified city in the Spanish empire. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Naples was home to great artists like Caravaggio, Salvator Rosa, and Bernini. Philosophers like Bernardino Telesio, Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella, and Giambattista Vico also lived there, along with writers like Gian Battista Marino. This showed that Naples was one of Europe's most important capitals. All these cultural figures helped bring about a new era, known as the Baroque period. Important women who hosted gatherings and supported artists, like Aurora Sanseverino, Isabella Pignone del Carretto, and Ippolita Cantelmo Stuart, played a big role in Naples' art and culture.

The stress of an increasingly crowded city led to a big rebellion in July 1647. The famous Masaniello led the common people in a violent uprising against the harsh foreign rule of the Spanish. The people of Naples declared a Republic and asked France for help. However, the Spanish put down the rebellion in April of the next year and defeated two attempts by the French fleet to land troops. In 1656, the plague killed almost half of the city's inhabitants. This marked the beginning of a period of decline for Naples.

From 1714 to 1799

The Spanish Habsburg rulers were replaced by Austrian ones in 1714. Then, in 1734, the two kingdoms were united under one independent crown, that of Charles of Bourbon. Charles improved the city by building the Villa di Capodimonte and the Teatro di San Carlo. He also welcomed philosophers like Giovan Battista Vico and Antonio Genovesi, legal experts like Pietro Giannone and Gaetano Filangieri, and composers like Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti. This first king from the House of Bourbon tried to make new laws and administrative changes, but these efforts stopped when news of the French Revolution reached the city. By that time, Charles's son, Ferdinand IV, was king. He joined a group of countries against France, including Great Britain, Russia, Austria, Prussia, Spain, and Portugal.

At the start of the 19th century, most of Naples' population were poor people called lazzarone. There was also a strong royal government and a small group of wealthy landowners. In January 1799, when French revolutionary troops entered the city, some middle-class people who supported the revolution welcomed them. However, they faced strong resistance from the royalist lazzari, who were very religious and did not support the new ideas. The short-lived Neapolitan Republic tried to gain popular support by ending old feudal privileges, but the common people rebelled. In June 1799, the republicans surrendered. After the old monarchy was restored, Admiral Horatio Nelson arrested the leaders of the revolution and had them executed.

From 1799 to 1861

The Parthenopaean Republic in Naples was put down by the British and Russians in 1799. This was followed in 1805 by a full invasion. In early 1806, Napoleon conquered the Kingdom of Naples. Emperor Napoleon first made his brother Joseph Bonaparte king, and then his brother-in-law and general Joachim Murat in 1808, when Joseph became king of Spain. Murat created a local government led by a mayor, which King Ferdinand left mostly unchanged when he got his kingdom back in 1815 after the Neapolitan War, where the Austrians defeated Murat. In 1839, Naples was the first city in Italy to have a railway, with the Naples-Portici line.

Despite a small cultural revival and the announcement of a Constitution on June 25, 1860, the gap between the royal court and the educated class continued to grow in the last years of the kingdom.

On September 6, 1861, the kingdom was conquered by Garibaldi's forces and handed over to the King of Sardinia. Garibaldi entered the city by train, arriving in the square that still bears his name today. In October 1860, a public vote confirmed the end of the Kingdom of Sicily and the start of a new Italian state, the united Kingdom of Italy.

Modern Times

The opening of the funicular railway to Mount Vesuvius inspired the famous song "Funiculì, Funiculà". This is just one of many well-known Neapolitan songs, like "'O sole mio", "Santa Lucia", and "Torna a Surriento," which are famous outside Italy too. On April 7, 1906, nearby Mount Vesuvius erupted, destroying Boscotrecase and seriously damaging Ottaviano.

During World War II, Naples was the first Italian city to fight back against the Nazi military occupation. Between September 28 and October 1, 1943, the people of the city rose up and pushed the Germans out. This event is known as the "four days of Naples." British armored patrols were the first Allied units to reach Naples. They were followed by American troops, who found Naples already free and continued towards Rome.

In 1944, another big eruption from Vesuvius happened. Pictures from this eruption were used in the movie The War of the Worlds.

Naples has become the most important transportation center in southern Italy. The Capodichino airport has flights across Europe. The city also has an important port that connects to many places in the Tyrrhenian Sea, including Cagliari, Genoa, and Palermo, often with fast ferries. Naples also has ferry connections to nearby islands and Sorrento, and fast train connections to Rome and the south. It is also known for its light railway, the Circumvesuviana.

Unemployment remains very high in Naples, with some estimates suggesting it's over 20% among working-age men. The industrial base is still small, and some large businesses, like car manufacturing plants on the outskirts, have closed and moved elsewhere. There is a large "hidden economy" (black market), so it's hard to get accurate numbers on the wealth it creates. Social services in the city have been under pressure recently due to an increase in immigration.

Italy's first Metropolitan railway (now Linea 2) opened in Naples in 1925.

Four funicular railways were opened between 1889 and 1931. Two of these connect the residential area of Vomero to the historic city center. One links Vomero with Chiaia, and another, in the western part of the city, connects Mergellina with Posillipo.

In 1927, Naples took in some nearby communities. The population of 450,000 in 1860 increased to 1,250,000 in 1971.

Naples has improved a lot in appearance over the past two decades. For example, Piazza del Plebiscito has returned to its historic role as the largest open square in the city, instead of being a parking lot as it was between the end of WWII and 1990. City landmarks like the San Carlo theater and the Galleria Umberto have been restored. A major ring road, the tangenziale di Napoli, has helped reduce traffic in and around the city. Also, major construction continues on the new underground railway system, the Naples Metro (metropolitana di Napoli). Even though it's not finished, it now provides easy transportation for the first time in the city's history from the higher parts of the Vomero hill into the downtown area. As a result of these improvements, tourism has increased. Naples became the world's 91st richest city by purchasing power in 2005, with a GDP of US$43 billion, surpassing Budapest and Zürich. Unemployment also decreased a lot between the 1990s and 2010.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Nápoles para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Nápoles para niños