Sicilian Vespers facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sicilian Vespers |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the conflict between the Guelphs and Ghibellines and the War of the Sicilian Vespers | |||||||

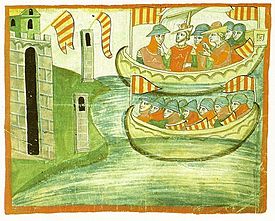

Sicilian rebels massacre the French soldiers Nuova Cronica by Giovanni Villani 14th. century |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Sicilian rebels (Staufer loyalists) |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John of Procida Ruggiero Mastrangelo Bonifacio de Camerana |

Charles I of Anjou Jean de Saint-Remy † |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4,000 killed | |||||||

The Sicilian Vespers (Italian: Vespri siciliani; Sicilian: Vespiri siciliani) was a successful rebellion in Sicily. It started at Easter in 1282. The people of Sicily rose up against their French ruler, King Charles I of Anjou. He had ruled the Kingdom of Sicily since 1266. The revolt happened after 20 years of French rule. The Sicilians did not like Charles's policies at all.

The rebellion began with an event in Palermo. It quickly spread across most of Sicily. In about six weeks, around 13,000 French people were killed by the rebels. King Charles lost control of the island. The Sicilians then asked Peter III of Aragon for help. He claimed the throne because his wife, Constance, was the rightful heir. Peter's involvement turned the rebellion into a bigger war, known as the War of the Sicilian Vespers.

Contents

Why the Rebellion Started

Popes and Emperors: A Long Fight

The rebellion had roots in a long power struggle. This was between the pope (the leader of the Catholic Church) and the Holy Roman Emperors from the Hohenstaufen family. They both wanted control over Italy. The popes especially wanted their own lands, called the Papal States. These lands were located between the Hohenstaufen lands in northern Italy and their Kingdom of Sicily in the south.

In 1245, Pope Innocent IV removed Frederick II from his position as emperor. He also encouraged people to oppose Frederick in Germany and Italy. When Frederick died in 1250, his son, Conrad IV of Germany, took over. After Conrad died in 1254, there was a period of confusion. Manfred, King of Sicily, Frederick's son, took control of the Kingdom of Sicily. He ruled from 1258 to 1266.

Manfred wanted to make peace with the pope. However, Pope Urban IV and later Pope Clement IV did not accept Manfred as the true ruler of Sicily. They first removed him from the church. Then, they tried to remove him by force.

The popes tried to get England to fight Manfred. But this did not work. So, Pope Urban IV chose Charles I of Naples to be the new King of Sicily. Charles invaded Italy. He defeated and killed Manfred in 1266 at the Battle of Benevento. Charles then became King of Sicily. In 1268, Conradin, Conrad's son, tried to claim the throne. But he was defeated at the Battle of Tagliacozzo and later executed. Charles was now the undisputed ruler of the Kingdom of Sicily.

Charles of Anjou and Unhappy Sicilians

Charles saw Sicily as a starting point for his plans in the Mediterranean Sea. He wanted to take over the Byzantine Empire and its capital, Constantinople. Constantinople had been captured by Crusaders in 1204. It was under Catholic rule for 57 years. But the Byzantines took it back in 1261. Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos was rebuilding the city. It was an important trade route to Europe.

The people of Sicily were unhappy. Their island played a very small role in Charles's empire. Sicilian nobles had no say in their own government. They did not get good jobs in other places, unlike Charles's French, Provençal, and Neapolitan subjects. Also, Charles used the heavy taxes he collected from Sicily to pay for his wars outside the island. This made Sicily a "donor economy." As historian Steven Runciman said, the Sicilians felt they were "being ruled to enable an alien tyrant make conquests from which they would have no benefit."

Byzantine agents also stirred up trouble to stop Charles's invasion plans. King Peter III of Aragon also helped. He was Manfred's son-in-law. Peter believed his wife, Constance, was the rightful heir to the Sicilian throne.

The Uprising Begins

The event is named after an uprising that started at sunset prayers (Vespers). This happened on Easter Monday, March 30, 1282. The place was the Church of the Holy Spirit just outside Palermo. Starting that night, thousands of French people living in Sicily were killed within six weeks. The exact events that started the uprising are not fully known. But different stories share common details.

According to Steven Runciman, Sicilians were celebrating at the church. A group of French officials joined them and started drinking. A sergeant named Drouet grabbed a young married woman from the crowd. Her husband then attacked Drouet with a knife and killed him. When other Frenchmen tried to get revenge, the Sicilian crowd attacked them, killing them all. At that moment, all the church bells in Palermo began to ring for Vespers. Runciman described the mood:

To the sound of the bells messengers ran through the city calling on the men of Palermo to rise against the oppressor. At once the streets were filled with angry armed men, crying "Death to the French" ("moranu li Francisi" in Sicilian language). Every Frenchman they met was struck down. They poured into the inns frequented by the French and the houses where they dwelt, sparing neither man, woman nor child. Sicilian girls who had married Frenchmen perished with their husbands. The rioters broke into the Dominican and Franciscan convents; and all the foreign friars were dragged out and told to pronounce the word "ciciri", whose sound the French tongue could never accurately reproduce. Anyone who failed the test was slain… By the next morning some two thousand French men and women lay dead; and the rebels were in complete control of the city.

Another historian, Leonardo Bruni (1416), said the Palermitans were having a festival outside the city. French soldiers came to check for weapons. They even checked the women, which started a riot. The French were attacked, first with rocks, then with weapons, and all were killed. News of this spread, leading to revolts across Sicily.

There is also a third story, similar to Runciman's. This story is part of the oral tradition on the island today. It says that John of Procida was the main planner of the rebellion. He was in contact with both Michael VIII Palaiologos and Peter III of Aragon. All three were later removed from the church by Pope Martin IV in 1282.

What Happened Next

After leaders were chosen in Palermo, messages spread across the island. Rebels were told to act quickly before the French could organize. In two weeks, the rebels controlled most of the island. Within six weeks, almost all of Sicily was under rebel control. Only Messina remained loyal to Charles for a while. But on April 28, Messina also rebelled. Its leader was Captain of the People Alaimo da Lentini. The first thing the islanders did was set fire to Charles's fleet in the harbor. It is said that when King Charles heard about his fleet's destruction, he exclaimed, "Lord God, since it has pleased You to ruin my fortune, let me only go down in small steps."

Charles's representative, Herbert, and his family were safe inside Mategriffon castle. But after talks, the rebels let Herbert and his family leave the island. They promised never to return. After order was restored, the townsmen declared themselves a free commune. This meant they would only answer to the pope. They chose leaders, including Bartholomaeus of Neocastro. He was important in these events and later wrote much about the revolt in his book Historia Sicula.

The leaders then sent a message to Emperor Michael. They told him that his enemy, Charles, was weakened. Only after this did they send ambassadors to Pope Martin IV. They asked for each city on the island to be recognized as a free commune. This would mean they were only under the authority of the Holy Church. The islanders hoped for a status like that of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa. These cities could govern themselves but were morally accountable to the Pope. However, the French pope strongly supported Charles. He told the Sicilians to accept Charles as their rightful king. But Martin did not understand how much the Sicilians hated the French, especially Charles. Charles ruled from Naples, not Palermo. He did not see the suffering caused by his officials. His officials on the island were far from his control. They were greedy, stole, and committed murder. They also collected high taxes from the poor peasants. This kept them poor and did not improve their lives.

Peter of Aragon Steps In

The pope refused the rebels' requests for free commune status. So, the Sicilians sent their requests to Peter III of Aragon. Peter was married to Constance. She was the daughter of Manfred, King of Sicily and granddaughter of the Hohenstaufen Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II. Of all that emperor's heirs, she was the only one not captured. She could claim her rights. Peter III supported his wife's claim to the entire Kingdom of Sicily.

Before the Vespers, Peter III built and equipped a war fleet. When the pope asked why he needed such a large fleet, Peter said it was for fighting the Saracens (Muslims) along the northern coast of Africa. He said he had trade interests there and needed to protect them. So, when Peter received a request for help from the Sicilians, he was conveniently on the north coast of Africa in Tunis. This was only 200 miles across the sea from Sicily. At first, Peter pretended not to care about the Sicilians' request. But after a few days, to show proper respect for the pope, he took advantage of the revolt. Peter ordered his fleet to sail for Sicily. He landed at Trapani on August 30, 1282. As he marched towards Palermo, his fleet followed close by the coast. Peter III of Aragon's involvement changed the uprising from a local revolt into a European war. When Peter arrived at Palermo on September 2, the people first greeted him with indifference. They saw him as just another foreign king replacing the old one. However, when Pope Martin clearly ordered the Sicilians to accept Charles, Peter promised the islanders that they would enjoy the old rights they had under the Norman king, William II of Sicily. So, he was accepted as a good second choice. He was crowned by acclamation at the cathedral in Palermo on September 4. He became Peter I of Sicily.

With the pope's blessing, Charles's counterattack came soon. His fleet from the Kingdom of Naples arrived and blocked the port of Messina. Charles tried several times to land troops on the island. But all his attempts were pushed back.

Paintings of the Sicilian Vespers

-

1821-1823 by Francesco Hayez

-

1859-1860 by Domenico Morelli

Other Meanings of "Sicilian Vespers"

- In 1594, the French King Henry IV was in long peace talks with the Spanish ambassador. He was bored because the Spanish would not agree to his terms. He said that the King of Spain should be more humble. If not, he could easily invade Spanish lands in Italy. He stated, "My armies could move so fast that I would have breakfast in Milan and dine in Rome." The Spanish ambassador replied, "Now then, if that is so, Your Majesty would surely make it to Sicily in time for Vespers."

- Two brothers from Sicily, David and Francis Rifugiato, named their band "The Sicilian Vespers" after this event. They released one album in 1988.

- Operation Sicilian Vespers (1992–98) was a security operation in Italy. It involved the Italian military and police working together. They fought against the mafia in Sicily.

See also

In Spanish: Vísperas sicilianas para niños

In Spanish: Vísperas sicilianas para niños