Greek Dark Ages facts for kids

| Geographical range | Greek mainland and Aegean Sea |

|---|---|

| Period | Ancient Greece |

| Dates | c. 1200–800 BC |

| Characteristics | Destruction of settlements and collapse of the socioeconomic system |

| Preceded by | Mycenaean Greece, Minoan civilization |

| Followed by | Archaic Greece |

The Greek Dark Ages (c. 1200–800 BC) was a time in ancient Greek history. It was once thought of as a mysterious period because not much was known about it. Historians used to call it the "Postpalatial Bronze Age" (around 1200–1050 BC) and the "Early Iron Age" (around 1050–800 BC). Today, experts are finding more information, so they don't see it as "dark" or "obscure" anymore.

This period began with a big event called the Late Bronze Age collapse. Around 1200–1150 BC, many great cities and palaces of the Mycenaeans were destroyed or left empty. Other powerful civilizations, like the Hittites, also faced major problems. Even the New Kingdom of Egypt struggled. After this collapse, there were fewer and smaller towns. This suggests many people died or moved away, possibly due to famine. In Greece, the special writing system called Linear B disappeared. It took a long time for a new writing system, the Greek alphabet, to appear around 800 BC.

Contents

What Happened After the Palaces? (Postpalatial Bronze Age)

Around 1200 BC, the grand Mycenaean palaces started to fall apart. This happened over several decades. One reason was likely internal problems within the cities. People might have rejected the palace rulers and their way of doing things. We know this because the Linear B writing and the palace buildings vanished. There were also fights between Mycenaean cities like Orchomenos and Thebes in the region of Boeotia. Even though some places like Thebes continued to be important for a while, the palaces, their art, and old burial customs were gone.

However, some places did well. On the island of Euboea, the town of Lefkandi grew quickly during this time (1200–1050 BC). It became a very important trading spot because it had a good harbor. Also, there is proof that Greek-speaking people arrived in Cyprus and on the Syrian coast at Al-Mina. These Greeks didn't take over Cyprus. Instead, they joined the society there as "economic and cultural migrants."

The Early Iron Age: A New Beginning

In the next period, the Early Iron Age (1050–800 BC), four main centers had more than 1000 people: Lefkandi, Athens, Argos, and Knossos. These places also showed signs of complex societies, with different levels of power. The designs on Greek pottery changed after 1050 BC. They became simpler, using mostly geometric shapes like lines and circles. This style is called Protogeometric and Geometric.

Historian Thomas R. Martin believes that between 950 BC and 750 BC, Greeks learned to write again. But this time, they used the alphabet of the Phoenicians instead of Linear B. They made a big change by adding letters for vowel sounds. This Greek alphabet eventually became the basis for the alphabet we use for English today.

It was once believed that Greeks lost all contact with other countries during this time. People thought there was little progress. But new discoveries have changed this idea. Archaeologist Alex Knodell found amazing things at Lefkandi in the 1980s. These finds showed that some parts of Greece were much richer and more connected than thought. A large building and a nearby cemetery had items from Cyprus, Egypt, and the Levant. These items showed that important people still had wealth and power. This proves that trade and cultural connections with the East, especially the Levant coast, grew stronger from about 900 BC onwards.

Life was hard for Greeks during the Dark Ages. The old Mycenaean ways of life, including strict social classes and kings, disappeared. But slowly, new ways of organizing society appeared. These new ideas eventually led to the rise of democracy in 5th century BC Athens. Important events that marked the end of the Dark Ages include the first Olympics in 776 BC. Also, the famous poems Iliad and Odyssey by Homer were created around this time.

Wars and Sea Peoples

The fall of the Mycenaeans during the Bronze Age collapse was once blamed on invaders like the Dorians or the mysterious Sea Peoples. However, the Sea Peoples might have been groups of pirates. They could have formed because of the collapse itself. These groups were likely made up of different people, such as sailors, workers, or soldiers from various backgrounds.

Around 1200–1150 BC, many large rebellions happened across the eastern Mediterranean. Jonathan Hall wrote in 2013 that the collapse of the Mycenaean palace system caused a lot of trouble and danger. He suggested that "some people – whether for reasons of safety or economic necessity – decided to abandon their former homes and seek a living elsewhere."

Culture and Daily Life

After the palaces collapsed, people stopped building huge stone structures. Wall paintings also seemed to disappear. The Linear B writing system was no longer used because the palace economy, which needed detailed records, had crashed. Important trade routes were lost, and many towns were abandoned. The number of people in Greece went down. The world of organized armies, kings, and officials vanished. Most of what we know about this period comes from burial sites and the items buried with the dead.

The cultures that emerged were spread out and independent. They didn't have one single style for art or daily objects. This means pottery styles, burial customs, and settlement structures were very different from place to place. For example, the Protogeometric style of pottery was simpler, using lines and curves. However, it's too simple to say there was just one "Dark Age Society." There were many different cultures across Greece at that time.

Some burial customs were unique to certain areas. For instance, Tholos tombs (round tombs) are found in Thessaly and Crete but not everywhere else. In Attica, people mostly burned their dead (cremation). But nearby in the Argolid, they buried them (inhumation). Some former Mycenaean palace sites, like Argos and Knossos, continued to be lived in. Other sites had a short period of growth before being abandoned. This might be linked to a "big-man social organization," where a leader's power comes from their personality and is not always stable. James Whitley sees Lefkandi in this way.

Some parts of Greece, like Attica, Euboea, and central Crete, recovered faster. But for most ordinary Greeks, daily life stayed much the same for centuries. They still farmed, wove cloth, worked with metal, and made pottery. However, they produced less, and items were mostly for local use. Some new ideas appeared around 1050 BC with the start of the Protogeometric pottery style. Potters used a faster wheel to make better vase shapes and a compass to draw perfect circles. They also achieved better glazes by firing clay at higher temperatures. Still, overall, art became simpler, and fewer resources were spent on creating beautiful pieces.

Greeks learned how to work with iron from Cyprus and the Levant. They used local iron ore that the Mycenaeans had ignored. This meant that edged weapons could now be made by more people, not just the elite. It's not clear exactly when iron weapons became stronger than bronze ones. But from 1050 BC, many small local iron industries appeared. By 900 BC, almost all weapons found in graves were made of iron.

The spread of the Ionic Greek dialect later suggests that people moved from mainland Greece to the coast of Anatolia (modern Turkey) as early as 1000 BC. Places like Miletus and Ephesus were settled. In Cyprus, some archaeological sites show Greek pottery. A Greek settlement from Euboea was set up at Al Mina on the Syrian coast. Trade networks started to revive around the 10th century BC. We know this from Attic Proto-geometric pottery found in Crete and at Samos.

Religion during the Greek Dark Ages seemed to continue the ideas from the Bronze Age. This included worshipping heroes and believing in the powers of the gods.

Cyprus After the Mycenaeans

Cyprus was home to a mix of people, including "Pelasgians" and Phoenicians. During this period, the first Greek settlements joined them. Potters in Cyprus created a beautiful new pottery style in the 10th and 9th centuries. It was called "Cypro-Phoenician" or "black on red." These small flasks and jugs likely held valuable liquids, like scented oil. Along with Greek pottery from Euboea, these items were widely traded. They have been found in places like Tyre and further inland in the late 11th and 10th centuries. Cypriot metalwork was also traded in Crete.

How Society Was Organized

During this time, Greece was probably divided into independent areas. These areas were organized by family groups and oikoi, which means households. These were the beginnings of the later Greek city-states, or poleis. Most Greeks lived in small settlements, not on isolated farms. It's likely that the main wealth for each family was their ancestral plot of land, called the kleros. A man needed this land to get married.

Excavations of Dark Age communities, like Nichoria in the Peloponnese, show how a Bronze Age town was abandoned around 1150 BC. But then it reappeared as a small village by 1075 BC. At this time, only about forty families lived there. They had plenty of good land for farming and raising cattle. The remains of a 10th-century BC building, possibly a chieftain's house, were found on a ridge. It was larger than other buildings but made of the same materials (mud brick and thatched roof). It might have also been a religious place or a shared storage area for food. Important people did exist in the Dark Age, but their living standards were not much higher than others in their village.

The Lefkandi Burial

Lefkandi on the island of Euboea was a rich settlement in the Late Bronze Age. In 1981, archaeologists found the largest 10th-century BC building known in Greece at a burial ground there. This long, narrow building, about 50 meters (164 feet) long, is sometimes called the heroon. It contained two burial shafts. In one, four horses were buried. The other held a man's ashes with his iron weapons and a woman's body. The woman was covered in gold jewelry.

The man's bones were placed in a bronze jar from Cyprus. The jar had hunting scenes on its rim. The woman wore gold coils in her hair, rings, and gold breastplates. She also had an old necklace from Cyprus or the Near East, made 200 to 300 years before her burial. An ivory-handled dagger was found near her head. The horses seemed to have been sacrificed. Some even had iron bits in their mouths. We don't know if the building was built just for the burial, or if the "hero" (local chieftain) was cremated and then buried in his grand house. Either way, the house was soon torn down, and the remains were used to form a circular mound over the walls.

Between this period and about 820 BC, wealthy people were cremated and buried near the eastern end of the building. This was like people wanting to be buried near a saint's grave. Over eighty more burials were found, with many imported objects. This shows that a rich elite tradition continued in Lefkandi.

The End of the Dark Ages

Archaeological findings show that Greece's economy was recovering well by the early 8th century BC. Cemeteries like the Kerameikos in Athens and Lefkandi, and holy places like Olympia, Delphi, or the Heraion of Samos, were filled with rich offerings. These included items from the Near East, Egypt, and Italy, made of rare materials like amber and ivory. Greek pottery was exported, showing trade with the Levant coast at places like Al-Mina and with the Villanovan culture in Italy.

Pottery decoration became more detailed. It included scenes with figures that might tell stories similar to those in Homeric Epic. Iron tools and weapons also improved. Renewed trade across the Mediterranean brought new supplies of copper and tin. This allowed people to make many fancy bronze objects, like tripod stands. These tripods were sometimes given as prizes in funeral games, like those Achilles held for Patroclus. Other coastal regions of Greece, besides Euboea, once again took part in the trade and cultural exchange of the eastern and central Mediterranean. Communities began to be governed by a group of important families (aristocrats), rather than by a single basileus or chieftain.

A New Way to Write

By the early 8th century BC, Greeks adopted a new Greek alphabet system. They learned it from the Phoenician alphabet. The Greeks changed the Phoenician writing system, which was used for the Phoenician language. The most important change was adding characters for vowel sounds. This created the first true alphabet. This new alphabet quickly spread around the Mediterranean. It was used to write not only Greek but also other languages in the eastern Mediterranean. As Greece started new settlements in the west, like Pithekoussae and Cumae in Sicily and Italy, their new alphabet spread even further.

An ancient Greek pot found in a grave at Pithekoussae (Ischia) dates from about 730 BC. It has a few lines written in the Greek alphabet that mention "Nestor's Cup." This seems to be the oldest written reference to the Iliad. The Etruscans in Italy also benefited from this new alphabet. Different versions of the Old Italic alphabet spread throughout Italy from the 8th century. Other versions of the alphabet also appear on the Lemnos Stele and in the alphabets of Asia Minor. However, the older Linear scripts were not completely abandoned. The Cypriot syllabary, which came from Linear A, was still used in Cyprus for Arcadocypriot Greek and Eteocypriot until the Hellenistic era.

Images for kids

-

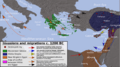

Map of the Late Bronze Age collapse (c. 1200 BC) in the Eastern Mediterranean

-

An Ancient Greek pair of terracotta boots. Early geometric period cremation burial of a woman, 900 BC. Ancient Agora Museum in Athens.

See also

In Spanish: Edad Oscura para niños

In Spanish: Edad Oscura para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |