Pottery of ancient Greece facts for kids

Pottery was very important in ancient Greece. Because it lasts a long time, we find many pieces of it today. Over 100,000 painted vases have been recorded! This huge amount of pottery helps us understand a lot about Greek society.

Broken pieces of pots from thousands of years ago are still the best way to learn about the daily life of ancient Greeks. Many pots were made locally for everyday use. However, fancier pottery from places like Attica was traded to other civilizations, such as the Etruscans in Italy. Different regions had their own unique pottery styles.

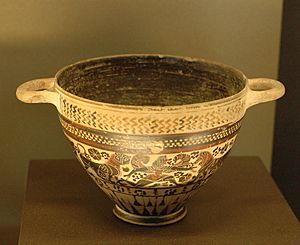

Ancient Greeks used many types and shapes of vases. Not all were just for practical use. Large Geometric amphorae were used as grave markers. Kraters in Apulia were placed in tombs as offerings. Panathenaic Amphorae were sometimes seen as beautiful art pieces. Some vases were highly decorated and meant for wealthy people to show off in their homes. For example, a krater was often used to mix wine with water.

Earlier Greek pottery styles are called "Aegean." These include Minoan pottery and Mycenaean pottery from the Bronze Age. After a difficult period called the Greek Dark Age, the styles changed. Sub-Mycenaean pottery slowly turned into the Protogeometric style, which is when ancient Greek pottery really began.

As vase painting grew, pots became more decorated. Geometric art was popular during the late Dark Age and early Archaic Greece. This period also saw the rise of the Orientalizing period. Pottery made in Archaic and Classical Greece first included black-figure pottery. Later, other styles like red-figure pottery and the white ground technique appeared. Styles like West Slope Ware were common during the later Hellenistic period, when vase painting started to decline.

Contents

What Were Greek Vases Used For?

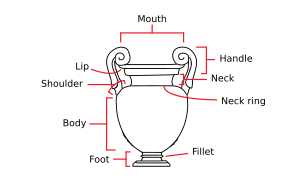

The names we use for Greek vase shapes are often just what archaeologists decided to call them. Sometimes, the names describe their original use or were their actual ancient names. Other times, early archaeologists tried to match pots with names from old Greek writings, which wasn't always easy.

To understand how Greek pottery was used, we can divide it into four main groups:

- Storage and transport vessels: These include the amphora, pithos, pelike, hydria, and pyxis.

- Mixing vessels: Mainly used for symposia, which were male drinking parties. Examples are the krater and dinos.

- Jugs and cups: Many types of kylix (also called cups), kantharos, phiale, skyphos, oinochoe, and loutrophoros.

- Vases for oils, perfumes, and cosmetics: These include the large lekythos, and the smaller aryballos and alabastron.

Besides these everyday uses, some vase shapes were special for rituals. Others were linked to sports and the gymnasium. We don't know the exact use of every vase, but experts make good guesses. Some had a purely ritual purpose.

Some vessels were designed as grave markers. Kraters marked the graves of men, and amphorae marked those of women. This is why some vases show funeral processions. White ground lekythoi held oil for offerings at funerals. Many of these had a hidden second cup inside. This made them look full of oil, even though they weren't, so they had no other practical use.

Greek pottery was traded internationally from the 8th century BC. Athens and Corinth were the main producers until the late 4th century BC. We can see how far this trade reached by looking at where these vases are found outside Greece. For example, many Panathenaic vases found in Etruscan tombs suggest a second-hand market. As Athens became less important, South Italian wares became popular for export in the Western Mediterranean during the Hellenistic period.

How Greek Pottery Was Made

Pottery can be damaged by breaking, wearing down, or fire. Making and firing a pot was a fairly simple process. The first thing a potter needed was clay. The clay from Attica had a lot of iron, which gave its pots an orange color.

Making the Clay

Cleaning the Clay (Levigation)

When clay was first dug up, it had rocks, shells, and other unwanted bits. To clean it, the potter mixed the clay with water. All the impurities would sink to the bottom. This process is called levigation or elutriation. It could be done many times. The more times it was done, the smoother the clay became.

Shaping on the Wheel

After cleaning, the potter kneaded the clay and placed it on a wheel. On the wheel, the potter could shape the clay into many different forms. Pottery made on a wheel dates back to about 2500 BC. Before that, people used the coil method to build the pot's walls. Most Greek vases were made on a wheel. However, some pieces, like the Rhyton, were made using molds. Decorative parts were sometimes shaped by hand or with molds and then added to the thrown pots. More complex pieces were made in parts and then joined together with a special clay paste when they were partly dry. Sometimes, a young person helped turn the wheel.

Painting with Clay Slip

After the pot was shaped, the potter painted it with a very fine clay slip. This paint was put on the areas that were meant to turn black after firing. This was done for both the black-figure and red-figure styles. For decoration, vase painters used brushes of different sizes, sharp tools for scratching lines, and probably single-hair tools for raised lines.

Studies show that the shiny black color on Greek pottery came from a special clay slip. This slip was rich in iron and had very little calcium. It was different from the clay used for the pot's body. The fine clay for the paint was made by adding things to the clay, like potash or wine dregs. Or, it was collected from clay beds after rain.

Firing the Pottery

Greek pottery was usually fired only once, using a very clever process. The black color was created by changing the amount of oxygen during firing. This was called three-phase firing.

First, the kiln (oven) was heated to about 920–950°C. All the vents were open, letting oxygen in. This turned both the pot and the slip a reddish-brown color. This is called an oxidizing condition.

Next, the vents were closed, and green wood was added. This created carbon monoxide, which turned the red iron in the slip black. At this stage, the temperature dropped a bit.

Finally, in a reoxidizing phase (around 800–850°C), the kiln was opened, and oxygen was let back in. The parts of the pot that were not covered by the slip turned back to orange-red. But the slipped areas, which had become very hard in the previous phase, could no longer oxidize and stayed black.

While this single firing with three stages seems efficient, some experts think that each stage might have been a separate firing. Modern experiments have shown that ancient vases might have been fired multiple times, especially if they needed repainting or color corrections. This "iron reduction technique" was figured out by many scholars and scientists over centuries.

Vase Painting Styles

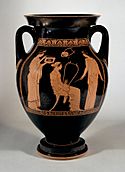

(1) Black-figure amphora by Exekias, showing Achilles and Ajax playing a game, around 540–530 BC.

(2) Red-figure scene of women playing music by the Niobid Painter.

(3) Bilingual amphora by the Andokides Painter, around 520 BC (Munich).

(4) Cylix of Apollo and his raven on a white-ground bowl by the Pistoxenos Painter.

The most famous part of ancient Greek pottery is its painted vessels. These weren't the everyday pots for most people, but they were affordable enough for many to own.

Not many examples of ancient Greek painting have survived. So, experts learn about the development of ancient Greek art partly through vase painting. It survives in large amounts and, along with Ancient Greek literature, helps us understand ancient Greek life and ideas.

History of Pottery Painting

Early Pottery: Stone and Bronze Ages

Greek pottery goes back to the Stone Age. Examples have been found in places like Sesklo and Dimini. More detailed painting on Greek pottery started in the Bronze Age with Minoan pottery and Mycenaean pottery. Some later examples show the detailed figure painting that would become very important.

Iron Age Styles

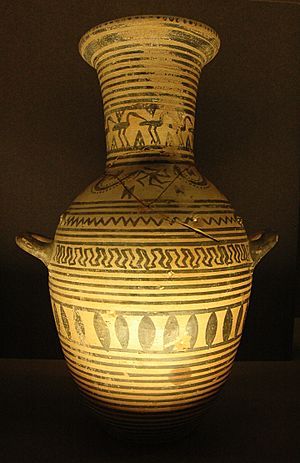

After many centuries of geometric designs, which became more and more complex, human and animal figures returned strongly in the 8th century BC. From the late 7th century to about 300 BC, styles with figures were at their best. These pots were widely traded.

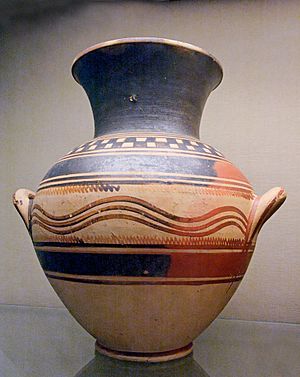

During the Greek Dark Age (11th to 8th centuries BC), the main style was protogeometric art. It mostly used circles and wavy lines. This was followed by the geometric art style in mainland Greece and other areas. This style used neat rows of geometric shapes.

The Archaic Greece period (8th to late 5th centuries BC) saw the start of the Orientalizing period. This was led by ancient Corinth. The simple stick-figures of geometric pottery became more detailed. New patterns replaced the geometric ones.

The most important classical pottery decoration came from Attica (Athens). Athenian pottery was the first to recover after the Greek Dark Age. It influenced the rest of Greece, especially places like Boeotia and Corinth. Athens was the main producer of vases. Painters and potters in other areas often copied the Athenian style.

By the end of the Archaic period, the styles of black-figure pottery, red-figure pottery, and the white ground technique were well established. They continued to be used during Classical Greece (early 5th to late 4th centuries BC). Athens became more important than Corinth because Athens created the red-figure and white-ground styles.

Protogeometric Style

Vases from the protogeometrical period (around 1050–900 BC) show that craft production returned after the fall of the Mycenaean culture. This was one of the few art forms during this time. By 1050 BC, life in Greece was stable enough for pottery making to improve. This style used only circles, triangles, wavy lines, and arcs. These shapes were placed carefully, probably with tools like compasses and multiple brushes. The site of Lefkandi is an important source of pottery from this period.

Geometric Style

Geometric art was popular in the 9th and 8th centuries BC. It brought new patterns, different from the Minoan and Mycenaean periods. These included meanders, triangles, and other geometric designs. We know the timeline for this art from pieces found in other countries.

In the early Geometric style (around 900–850 BC), only abstract patterns were used. This was called the "Black Dipylon" style, known for its extensive use of black varnish. In the Middle Geometric period (around 850–770 BC), figures started to appear. At first, these were bands of animals like horses, deer, goats, and geese, mixed with geometric bands. The decorations became more complex. Painters didn't like empty spaces, so they filled them with meanders or swastikas. This is called horror vacui (fear of the empty).

In the middle of the 8th century BC, human figures appeared. The most famous examples are on vases found in Dipylon, a cemetery in Athens. These large funeral vases mainly show chariots, warriors, or funeral scenes. The bodies are shown in a geometric way, except for the calves, which stick out. Soldiers had a shield shaped like a diabolo, called a "Dipylon shield." Legs and necks of horses, and chariot wheels, were shown side-by-side without perspective. The artist of these pieces, called the Dipylon Master, can be identified on several large amphorae.

At the end of this period, scenes from mythology appeared. This was probably when Homer wrote down the stories of the Trojan War in the Iliad and the Odyssey. However, it's hard for us to be sure about the meaning of these scenes. A fight between two warriors could be a Homeric duel or just a simple combat. A sinking boat could be Odysseus's shipwreck or any unlucky sailor.

Finally, local art schools appeared in Greece. Athens was the main producer of vases. Painters and potters in places like Corinth, Boeotia, Argos, Crete, and the Cyclades often followed the Attic style. But from about the 8th century BC, they started creating their own styles. Argos focused on figures, while Crete kept more abstract designs.

Orientalizing Style

The Orientalizing style came from cultural exchange in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean in the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Trade with cities in Asia Minor brought Eastern art to Greece. This influenced a very stylized but recognizable art style. Ivories, pottery, and metalwork from places like Syria and Phoenicia came to Greece. This new style first developed in Corinth (called Proto-Corinthian) and later in Athens (called Proto-Attic) between 725 BC and 625 BC.

It featured new motifs like sphinxes, griffins, and lions. Also, non-mythological animals were arranged in rows across the vase. Painters also started using lotus flowers or palmettes. Human figures were rare. When they appeared, they were in silhouette with some scratched details. This might be where the black-figure style came from.

Corinthian pottery was traded all over Greece. Its techniques reached Athens, leading to a less Eastern style there. During this Proto-Attic period, Orientalizing patterns appeared, but the figures were not very realistic. Painters preferred scenes from the Geometric Period, like chariot processions. However, they started using line drawing instead of silhouettes. In the mid-7th century BC, the black and white style appeared: black figures on a white background, with added colors for skin or clothing. Athenian clay was more orange than Corinthian clay, so it wasn't as easy to show skin color.

Places like Crete and the Cyclades islands liked "plastic" vases. These were vases where the body or neck was shaped like an animal or human head. At Aegina, the griffin head was a popular shape. The Melanesian amphoras from Paros showed little influence from Corinth. They liked epic scenes and filled all empty spaces with swastikas and meanders.

Another major style was the Wild Goat Style. It's often linked to Rhodes because of discoveries there. But it was common across Asia Minor, with centers in Miletus and Chios. Two main shapes were oenochoes (jugs) and dishes. The decoration was in stacked rows with stylized animals, especially wild goats, chasing each other. Many patterns filled the empty spaces.

Black-Figure Technique

Black-figure is what most people imagine when they think of Greek pottery. It was very popular in ancient Greece for many years. This style was common from about 620 to 480 BC. The technique of scratching details onto silhouetted figures was invented in Corinth in the 7th century. From there, it spread to other city-states like Sparta, Boeotia, Euboea, the East Greek islands, and Athens.

Corinthian pottery shows how animal and human figures were treated. Animal patterns were more important and experimental in the early black-figure period in Corinth. As Corinthian artists got better at drawing human figures, the animal rows became smaller. By the mid-6th century BC, the quality of Corinthian pottery dropped. Some Corinthian potters even used a red slip to make their pots look like the better Athenian ones.

In Athens, researchers found the earliest examples of vase painters signing their work. The first was a dinos by Sophilos (around 580 BC). This shows artists were becoming more ambitious, especially when making large grave markers, like Kleitias's François Vase. Many experts believe the best black-figure work was done by Exekias and the Amasis Painter. They were known for their great sense of composition and storytelling.

Around 520 BC, the red-figure technique was developed. It was slowly introduced with bilingual vases by artists like the Andokides Painter, Oltos, and Psiax. Red-figure quickly became more popular than black-figure. However, black-figure continued to be used for the special Panathenaic Amphora well into the 4th century BC.

Red-Figure Technique

The red-figure technique was an Athenian invention from the late 6th century. It was the opposite of black-figure, which had a red background. With red-figure, artists could add details by painting directly, not just scratching. This allowed for new ways to show things, like three-quarter views, more detailed body parts, and a sense of depth.

The first red-figure painters worked in both red- and black-figure styles, as well as others like Six's technique and white-ground. However, within 20 years, artists started to specialize. The Pioneer Group, for example, only used red-figure for their figures. They still used black-figure for some early plant decorations. The Pioneers, like Euphronios and Euthymides, shared similar goals.

The next generation of late Archaic vase painters (around 500 to 480 BC) made the style more natural. You can see this in how they gradually changed the way eyes were drawn. During this time, painters also specialized in either pots or cups. The Berlin and Kleophrades Painters were known for pots, while Douris and Onesimos were known for cups.

By the early to high classical era of red-figure painting (around 480–425 BC), several distinct schools had developed. The Mannerists, linked to the workshop of Myson and led by the Pan Painter, kept older features like stiff clothing and awkward poses. They combined this with exaggerated movements. In contrast, the school of the Berlin Painter, including the Achilles Painter, preferred natural poses, often with a single figure against a black background. Polygnotos and the Kleophon Painter were part of the school of the Niobid Painter. Their work shows the influence of the Parthenon sculptures in both themes and composition.

Towards the end of the century, the "Rich" style of Athenian sculpture, seen in the Nike Balustrade, was reflected in vase painting. Artists paid more attention to small details like hair and jewelry. The Meidias Painter is often linked to this style.

Vase production in Athens stopped around 330–320 BC, possibly because Alexander the Great took control of the city. It had been slowly declining throughout the 4th century, along with Athens' political power. However, vase production continued in the 4th and 3rd centuries in the Greek colonies of southern Italy. Five regional styles can be seen there: Apulian, Lucanian, Sicilian, Campanian, and Paestan. Red-figure work thrived there, with added colors and, in the case of the Black Sea colony of Panticapeum, gilded work in the Kerch Style. Important artists like the Darius Painter and the Underworld Painter, active in the late 4th century, created crowded, colorful scenes that showed complex emotions.

White-Ground Technique

The white-ground technique was developed at the end of the 6th century BC. Unlike black-figure and red-figure, its colors came from paints and gilding on a white clay surface, not just from firing clay slips. This allowed for more colors, though the vases were less visually striking. The technique became very important during the 5th and 4th centuries, especially for small lekythoi used as grave offerings. Key artists include its inventor, the Achilles Painter, as well as Psiax, the Pistoxenos Painter, and the Thanatos Painter.

Relief and Plastic Vases

Vases with raised designs (relief) and shaped like figures (plastic) became very popular in the 4th century BC and continued into the Hellenistic period. They were inspired by the "rich style" that developed in Attica after 420 BC. These vases often had many figures, used added colors (pink, blue, green, gold), and focused on female mythological figures. Theater and performances were also a source of inspiration.

The Delphi Archaeological Museum has some great examples of this style. One vase shows Aphrodite and Eros. It has a round, cylindrical base and a vertical handle. The female figure (Aphrodite) is seated, wearing a cloak. Next to her stands a winged male figure. Both figures wear leaf wreaths, and their hair has traces of gold paint. Their faces are stylized. The vase has a white background and traces of blue, green, and red paint. It dates to the 4th century BC.

In the same room, there's a small lekythos with a shaped decoration of a winged dancer. The figure wears a Persian head covering and an Eastern dress. This shows that Eastern dancers, possibly slaves, were fashionable even then. The figure is also covered with white paint. The vase is 18 centimeters tall and dates to the 4th century BC.

Hellenistic Period Pottery

The Hellenistic period, which began with the conquests of Alexander the Great, saw the black-figure and red-figure pottery styles almost disappear. However, new styles emerged, such as West Slope Ware in the east, the Centuripe Ware in Sicily, and the Gnathia vases to the west. Outside mainland Greece, other regional Greek traditions developed, like those in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). These included various styles such as Apulian, Lucanian, Paestan, Campanian, and Sicilian.

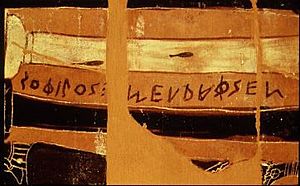

Inscriptions on Pottery

Inscriptions on Greek pottery were of two types: scratched (the earliest from the 8th century BC) and painted (which appeared a century later). Both types were common on painted vases until the Hellenistic period, when the practice of writing on pots seemed to stop. They are most often found on Athenian pottery.

Different kinds of inscriptions can be seen. Potters and painters sometimes signed their work. Potters used epoiesen (made it), and painters used egraphsen (drew it). Trademarks appeared from the 6th century on Corinthian pieces. These might have belonged to a merchant who exported the pottery. The names of people who ordered the pots were sometimes recorded. Also, the names of characters and objects shown on the vases were written. Sometimes, a short bit of dialogue would go with a scene, like "Dysniketos's horse has won," announced by a herald on a Panathenaic amphora.

More puzzling are the kalos and kalee inscriptions. These might have been part of a courtship ritual in Athenian high society. But they are found on many different vases, not just those used in social settings. Finally, there are abecedaria (alphabet lists) and nonsense inscriptions, though these are mostly on black-figure pots.

Terracotta Figurines

Greek terracotta figurines were another important type of pottery. At first, they were mostly religious offerings. But later, they became purely decorative. The famous Tanagra figurines, though made in other places too, are a key example. Earlier figurines were usually votive offerings placed in temples.

Pottery and Metalwork

Many clay vases were inspired by metal objects made of bronze, silver, and sometimes gold. Wealthy people increasingly used metal vessels for dining. However, these were not placed in graves, as they would have been stolen. Metal vessels were often seen as valuable items that could be melted down and reused if needed. Very few metal vessels have survived because they were often melted down.

In recent years, many experts have questioned the traditional idea that metalwork always came first. They now think that many painted vases were made specifically to be placed in graves. These clay vases were a cheaper substitute for metalware in both Greece and Etruria. The painting itself might also have copied designs found on metal vessels more closely than once thought.

The Derveni Krater, found near Thessaloniki, is a large bronze volute krater from about 320 BC. It weighs 40 kilograms and is beautifully decorated with a 32-centimeter-tall band of figures. These figures show Dionysus surrounded by Ariadne and her group of satyrs and maenads.

The alabastron got its name from alabaster, the stone it was originally made from. Glass was also used, mostly for small, fancy perfume bottles. Some Hellenistic glass was as good as metalwork and probably just as expensive.

See also

In Spanish: Cerámica griega para niños

In Spanish: Cerámica griega para niños

- Conservation and restoration of ancient Greek pottery

- Tanagra figurine

- Kerameikos Archaeological Museum

- Ancient Greek crafts

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |