Hydria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hydria |

|

|---|---|

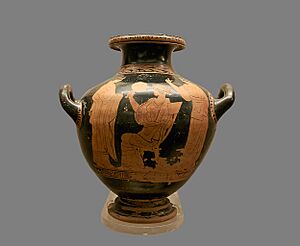

A hydria, around 470-450 BC

|

|

| Material | Ceramic and bronze |

| Size | Medium-volume container varying from 25cm to 50 cm, able to be carried by one or more people. |

| Writing | Painters would sometimes inscribe their name onto the hydria. |

| Symbols | Mythological stories were often painted onto the hydria, as well as scenes of daily life, such as the collection of water. |

| Created | Geometric period, archaic period, classical period Hellenistic period |

| Discovered | 19th century |

| Culture | Ancient Greek |

A hydria (Greek: ὑδρία; plural hydriai) is a special type of Greek pottery. It was made between the late Geometric period (7th century BC) and the Hellenistic period (3rd century BC). The word "hydria" means 'jug' in Greek. This name was even stamped on some hydrias themselves!

While hydrias were mainly used for carrying water, they had many other uses too. Over time, hydrias changed in shape, size, and the materials they were made from. Many were decorated with detailed pictures. These pictures often showed stories from Greek myths or scenes from everyday life. This gives us a great look into Ancient Greek culture and how people lived back then.

Contents

What Was a Hydria Used For?

Originally, hydrias were made to collect water. But they also held oil and even votes from judges. The design of the hydria made it easy to collect and pour liquids. It had three handles: two flat ones on the sides and one upright handle on the back.

Around the 5th century BC, the hydria's shape changed. It went from having a wide body and round shoulders to flatter shoulders that met the body at an angle. This made it easier to carry water to and from homes. The upright handle also helped people pour liquids easily, like when mixing wine in a krater.

Hydrias as Urns and Prizes

Hydrias were also used as urns to hold ashes after someone died. This was especially true for a type called the Hadra hydria. A special official would record the person's name, where they were from, and the burial date.

Bronze hydrias were often given as prizes in tournaments and competitions. Old paintings on vases show winners carrying a hydria as their reward. Some hydrias even have inscriptions saying they were prizes. Because bronze hydrias were so valuable, they were also given as gifts to sanctuaries (holy places).

Different Kinds of Hydrias

The Classic Hydria

The first hydrias were large, with round shoulders and a full body. This shape was common for black-figure pottery in the 6th century BC. They had a clear shoulder, a distinct neck, and a lip that hung over. These hydrias had three handles: two horizontal ones on the sides and one vertical one on the back. They were usually between 33 cm and 50 cm tall. The outside was shiny, but the inside was not.

The Kalpis

The kalpis became popular in the 5th century BC. It was a favorite for red-figure painters. The kalpis was usually smaller than the classic hydria, from 25 cm to 42 cm tall. Its body, shoulder, and neck had a smooth, continuous curve. A very small hydria was sometimes called a hydriske or hydriskos. The kalpis's upright handle was round and attached at the lip, not the rim. Its rim curved inward, unlike the classic hydria's lip.

The Hadra Hydria

This style appeared during the Hellenistic period. Hadra hydrias had a wide, short neck, a low base, and a flaring foot. Their vertical handle was ribbed, not round, and their side handles were gently curved. They got their name from "Hadra," a place in Alexandria, where they were first found in the 1800s.

There were two main types of Hadra hydrias:

- Whitewashed Hadra Hydrias: These had a thick layer of white paint for colorful decoration. They were made in Egypt and often placed in Tombs.

- "Clay Ground" Hadra Hydrias: These used dark brown or black paint directly on the clay surface. They were made in Crete.

Bronze Hydrias

Bronze hydrias started to be made from the 4th century BC onwards. They were highly valued. They had a shallow neck and a large body. They were polished to be very shiny and often decorated with silver inlays. Bronze hydrias could also have pictures or patterns. For example, one showed Dionysus (the god of wine) and a satyr. Unlike other hydrias, bronze ones usually had a lid. We know this because of marks from soldering and holes for rivets on their rims. Having a lid meant they could be used as funerary urns. Over 330 bronze hydrias have been found, some complete and some in pieces.

How Hydrias Were Made

Making the Body

Potters started by "throwing" a large ball of clay on a potter's wheel. "Throwing" means to twist or turn the clay. The clay ball was shaped into a tall cylinder. Then, the potter would expand it outwards using their hands. They would press their hands together, one inside and one outside, to form the upward curve of the hydria. At the shoulder, the potter would smooth the clay inwards to create the base of the neck. A rib tool was used to smooth out the shoulder and remove any lines from throwing. The body was then cut from the wheel and left to dry.

Making the Neck, Mouth, and Lip

The neck, mouth, and lip were made separately, right side up. A smaller lump of clay was expanded, thinned, and shaped. Once a short cylinder was formed, the clay was angled outward to create the lip. The lip was rounded with a sponge. This part was then cut off the wheel and left to dry. The neck walls were thicker at the bottom and got thinner towards the lip, similar to a neck amphora.

Joining the Parts

Once the body and neck were dry, they were joined together. The potter put a special clay mixture called a slip between the shoulder and the neck. They would put a hand inside the hydria where the parts met and apply the slip. This bonded the neck and shoulder. The joint was smoothed out so it looked like one piece.

Shaping the Base

After the vessel had dried to a leather hard stage (firm but still workable), the potter turned the hydria upside down. They then shaped its base into a parabolic shape.

Making the Foot

The foot was made upside down from a small ball of clay that was spread outwards. The potter used their thumbs to shape the walls of the foot. Their fingers rounded the edge, giving it a Torus (doughnut-like) shape. It was cut from the wheel and left to dry. Once dry, it was attached to the rest of the hydria using slip.

Adding the Handles

A hydria has three handles: two horizontal ones on the sides and one vertical one on the back. The horizontal handles were pulled from balls of clay and attached below the shoulder. They were round and curved upwards. The vertical handle was also pulled from clay, but it had a ridge in the middle and was oval-shaped. It was attached at the lip and shoulder. The handles were then polished by hand, not on the wheel.

Making Bronze Hydrias

Bronze hydrias were made from two sheets of bronze. The thin walls were hammered into shape. If a bronze hydria had a noticeable shoulder, it was hammered in two parts. First, a metal disk was shaped for the neck. Then, a tube that flared at both ends was welded where the shoulder met the neck. Other parts, like the foot, handles, and mouth, were cast (poured into a mold) and then attached by welding or soldering. Bronze hydrias were polished to be bright and shiny. They were also decorated with silver inlays. Their handles sometimes had patterns or objects, like Palmettes (fan-shaped designs).

What We Learn from Hydrias

Hydrias teach us a lot through their decorations and inscriptions (writings). The decorations often show mythological stories and scenes from daily life. The inscriptions can tell us the potter's name, the date it was made, and what it was used for. These details help experts understand Ancient Greek culture and how pottery changed over time.

Decorations can also show how a hydria was used. For example, bronze hydrias with figures about love were given as gifts to brides. Those decorated with Dionysus were used by men at fancy dinner parties.

The Caputi Hydria

The Caputi hydria gives us a peek into the lives of working women in ancient Athens. For a long time, people thought women in Athens (5th century BC) only stayed home. But the Caputi hydria shows women decorating a vase in a pottery workshop. While some experts debate if it was a metal workshop, many agree this hydria proves that women were painters and worked in trades.

Inscribed Hadra Hydrias

Many Hadra hydrias found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art have inscriptions. These writings include the names of artists, potters, important historical figures, and dates. These inscriptions are very important! They help us figure out when the pottery was made, which helps create a timeline for ancient Greek pottery. They also mention important people from that time, filling in gaps that written records might miss. For example, one Hadra hydria inscription translates to: "Year 9; Sotion son of Kleon of Delphi, Member of the Sacred Embassy announcing the Soteria; by Theodotos, agorastes." From this, we can guess the date was around 212 BC. It also tells us about political jobs and government officials back then.

The Friedlaender Hydria

This 6th-century black-figure hydria is covered with many mythological scenes. On the main body, it shows Hercules fighting the Triton (also known as Nereus or the Old Man of the Sea). Poseidon and Amphitrite watch them. To the left of Hercules are Hermes and Athena, who were often with Hercules.

On the shoulder of the hydria, five figures are about to fight. The person in the middle is a herald. The figures on either side wear Corinthian helmets and armor, holding Boeotian shields. This scene shows the mythological battle between Hector and Ajax from the Iliad. The central figure is the herald Idaios, who tries to stop the fight. The pictures and shape of the Friedlaender hydria help experts place it in the 6th century BC. This helps create a timeline for different types of hydrias.

See also

In Spanish: Hidria para niños

In Spanish: Hidria para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |