Petrarch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francesco Petrarca

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Altichiero

|

|

| Born | Francesco Petracco 20 July 1304 Comune of Arezzo |

| Died | 19 July 1374 (aged 69) Arquà, Padua |

| Resting place | Arquà Petrarca |

| Occupation | Scholar, poet |

| Language | Italian, Latin |

| Nationality | Aretine |

| Alma mater | University of Montpellier University of Bologna |

| Period | Early Renaissance |

| Literary movement | Renaissance humanism |

| Notable works | Triumphs Il Canzoniere |

| Notable awards | Poet laureate of Padua |

| Partner | unknown woman or women |

| Children | Giovanni (1337–1361) Francesca (born in 1343) |

| Relatives | Eletta Canigiani (mother) Ser Petracco (father) Gherardo Petracco (brother) |

Francesco Petrarca (born July 20, 1304 – died July 18 or 19, 1374), often called Petrarch in English, was a famous scholar and poet. He lived during the early Italian Renaissance and was one of the first humanists.

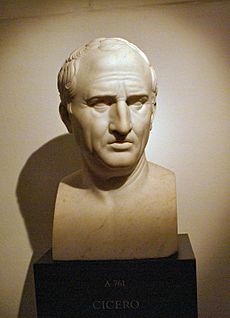

Petrarch is known for finding old letters written by Cicero, a famous Roman speaker. This discovery helped start the 14th-century Italian Renaissance. His poems, especially his sonnets, were very popular across Europe. They became a guide for other poets writing lyrical poetry. Petrarch also created the idea of the "Dark Ages" to describe the time before the Renaissance.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Petrarch was born in Arezzo, a city in Tuscany, Italy, on July 20, 1304. His father was Ser Petracco and his mother was Eletta Canigiani. His birth name was Francesco Petracco, which was later changed to the more formal Latin name, Petrarca. His younger brother was born in 1307.

Petrarch spent his early years in a village called Incisa, near Florence. Later, his family moved to Avignon and Carpentras in France. They moved because Pope Clement V had moved the Church's headquarters to Avignon in 1309.

Petrarch studied law at the University of Montpellier from 1316 to 1320. He then continued his law studies at the University of Bologna from 1320 to 1323. His father was a notary (a legal professional) and wanted Petrarch and his brother to follow in his footsteps.

However, Petrarch found law boring. He was much more interested in writing and Latin literature. He felt that his seven years studying law were wasted. He even thought the legal system was unfair. Sometimes, he was so distracted by his love for books that his father would throw his books into a fire!

Petrarch's Career and Travels

After his parents passed away, Petrarch and his brother Gherardo returned to Avignon in 1326. Petrarch found work in various church offices. These jobs gave him plenty of time to focus on his writing.

His first major work was Africa. This was a long poem written in Latin about Scipio Africanus, a great general from ancient Rome. This poem made Petrarch famous all over Europe. On April 8, 1341, he was crowned a poet laureate in Rome. This was a very special honor, given to only a few poets since ancient times.

Petrarch loved to travel across Europe. During his journeys, he found many old handwritten books and letters. In 1345, he discovered a collection of letters by Cicero in a library in Verona. These letters, called Epistulae ad Atticum, were not known to exist before Petrarch found them.

Later in his life, Petrarch traveled through northern Italy. He was known as an important scholar and a diplomat (someone who represents their country). In 1361, he became a canon in Monselice, near Padua. Between 1361 and 1369, another famous Italian writer, Giovanni Boccaccio, visited Petrarch twice.

Italian Poetry and Laura

Petrarch is most famous for his Italian poems. His main collection is called Rerum vulgarium fragmenta, which means "Fragments of Vernacular Matters." This book has 366 poems, mostly love poems. It is also known as 'canzoniere' (meaning 'songbook'). He also wrote I trionfi ("The Triumphs"), a long poem with six parts.

The Rerum vulgarium fragmenta is mainly a collection of Petrarch's love poems written for a woman he called Laura. Petrarch said he first saw Laura in a church in Avignon on April 6, 1327. Seeing her made him feel strong love and passion.

Some people believe Laura was Laura de Noves, the wife of Count Hugues de Sade. Petrarch's writings don't give many details about Laura. He describes her as beautiful, with fair hair and a calm, graceful way of being. Petrarch and Laura likely did not have much personal contact. In his writings, he mentioned that she refused him because she was already married. So, he put all his feelings into his love poems.

The Rerum vulgarium fragmenta is divided into two parts. The first part has poems Petrarch wrote before he met Laura. The second part contains poems he wrote after meeting her. When Laura died in 1348, Petrarch found that his sadness was as hard to deal with as his earlier feelings of longing. Some people wonder if Laura was a real person or just an idea, especially since the name "Laura" sounds like "laurels" (the wreaths given to poets). But Petrarch always said she was real.

This collection of poems is considered a masterpiece of Italian literature. It helped make the Italian language important for writing poetry and stories.

Petrarch's Philosophy

Petrarch is often called the "father of humanism" and the "father of the Renaissance". He inspired a way of thinking called humanism, which helped lead to the great burst of art and learning during the Renaissance. Humanism focuses on the value of human beings and their achievements. Petrarch believed it was very important to study ancient history and literature. He thought this study helped people understand human thoughts and actions.

Petrarch was a very religious Catholic. He believed that being religious and trying to reach your full potential as a human being could go together. He didn't see them as being in conflict.

Petrarch's Family Life

Petrarch worked for the Church, which meant he was not allowed to marry. However, he had two children. His son, Giovanni, was born in 1337. His daughter, Francesca, was born in 1343. Petrarch later made them legitimate, meaning they were legally recognized as his children.

Sadly, Giovanni died from the plague in 1361. Francesca married Francescuolo da Brossano in the same year. In 1362, after her daughter Eletta was born, Francesca and her family moved to Venice to live with Petrarch. They were trying to escape the plague that was spreading across Europe. A second grandchild, Francesco, was born in 1366 but died young. Francesca and her family lived with Petrarch in Venice for five years, from 1362 to 1367.

Petrarch's Later Years and Death

Around 1368, Petrarch and Francesca's family moved to a small town called Arquà. It is in the Euganean Hills near Padua. Petrarch spent his last years there, focusing on religious thoughts. He died in his house in Arquà on July 18 or 19, 1374.

Today, his house in Arquà is a museum. It has a permanent display of Petrarch's works and interesting items. There's even a tomb for an embalmed cat, which people long believed was Petrarch's pet. However, there's no real proof that Petrarch actually had a cat.

Petrarch's Will

Petrarch wrote his will on April 4, 1370. In it, he left 50 florins to his friend Boccaccio. He also left a horse, a silver cup, a lute, and a statue of the Madonna to his brother and friends. His house in Vaucluse went to its caretaker. Most of his property went to his son-in-law, Francescuolo da Brossano. Brossano was told to give half of it to "the person to whom, as he knows, I wish it to go." This was likely his daughter, Francesca.

Petrarch had promised his collection of important old books to Venice in exchange for a palace. But this plan was probably canceled when he moved to Padua, which was an enemy of Venice, in 1368. His library was later taken by the rulers of Padua. Today, his books and manuscripts are spread out in different places across Europe.

Interesting Facts About Petrarch

- Petrarch's father and the famous poet Dante Alighieri were friends.

- The way Petrarch wrote helped shape the modern Italian language.

- He was chosen as a model for Italian writing style by a group called the Accademia della Crusca.

- Petrarch loved writing letters to his friends and family. Giovanni Boccaccio was one of his close friends he wrote to often.

- He also wrote letters to historical figures who had been dead for a long time, like Cicero and Virgil.

- Cicero, Virgil, and Seneca were his favorite writers and models.

- He traveled widely in Europe and worked as an ambassador. Because he traveled for fun, some people call him "the first tourist".

- Petrarch is known for creating the idea of a historical "Dark Ages". Most modern historians now find this idea to be not entirely accurate.

- He was a big fan of Latin and wrote most of his works in that language. His Latin writings include scholarly works, personal essays, letters, and poems.

- Many of his Latin writings are hard to find today, but some have been translated into English.

- After his death, many composers set Petrarch's poems to music, especially Italian madrigal composers in the 16th century. Only one musical setting from his lifetime still exists.

- Petrarch was said to be about 1.83 meters (about six feet) tall, which was very tall for his time.

- He is also known for being one of the first and most famous people interested in Numismatics (collecting coins). He would visit Rome and buy ancient coins from peasants. He loved being able to identify Roman emperors from these coins.

Petrarch's Legacy

Petrarch's influence can be seen in the works of other poets like Serafino dell' Aquila and Marin Držić.

The Romantic composer Franz Liszt set three of Petrarch's Sonnets to music for singing. He later changed these pieces for solo piano.

In 1991, the Modernist composer Elliott Carter wrote a flute piece called Scrivo in Vento. This piece was partly inspired by Petrarch's Sonnet 212. It was first performed on Petrarch's 687th birthday.

Images for kids

-

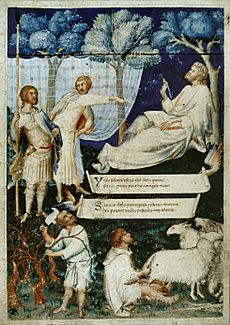

Petrarch's Virgil (title page) (c. 1336) by Simone Martini

-

Petrarch's Arquà house near Padua where he retired

-

Petrarch helped bring back the works of the ancient Roman Senator Cicero

See also

In Spanish: Petrarca para niños

In Spanish: Petrarca para niños

- Otium