Caesar's civil war facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Caesar's civil war |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crisis of the Roman Republic | |||||||

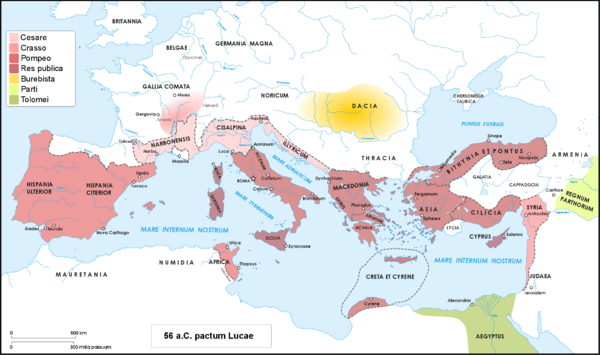

Map of the Roman Republic in the mid-1st century BC |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Early 49 BC: 10 legions | Early 49 BC: 15 legions | ||||||

Caesar's Civil War was a big fight in ancient Rome from 49 to 45 BC. It was a civil war, meaning Romans fought against other Romans. The two main leaders were Julius Caesar and Pompey. They were both powerful generals and politicians.

The war started because Caesar had gained a lot of power and fame after conquering Gaul (modern-day France). When he was supposed to return to Rome, the Roman Senate (Rome's governing council) and Pompey wanted him to give up his armies. Caesar refused and marched his army into Italy, starting the war.

The fighting happened in many places, including Italy, Greece, Egypt, and Spain. Caesar won the most important battles, especially the Battle of Pharsalus in Greece. Pompey was defeated and later killed in Egypt. Caesar eventually won the war, becoming the most powerful man in Rome. This war was a major event that led to the end of the Roman Republic and the start of the Roman Empire.

Contents

Why the War Started

The main reason for the war was a disagreement about Caesar's power. He had been away in Gaul for nearly ten years, leading the Gallic Wars. During this time, he became very successful and popular with his soldiers. He also gained a lot of wealth.

Before the war, Caesar, Pompey, and another rich Roman named Crassus had formed a secret alliance called the First Triumvirate. They worked together to get what they wanted in Roman politics. But after Crassus died in battle and Caesar's daughter (who was married to Pompey) also passed away, the alliance fell apart.

Pompey and the Senate became worried about Caesar's growing power. They wanted him to return to Rome as a private citizen, without his army. This would have made him lose his special legal protection and political influence. Caesar wanted to run for a second term as a Roman consul (one of the two highest elected officials) without giving up his army first. He believed this was his right.

The Senate, pushed by Pompey and other powerful senators, demanded that Caesar give up his provinces and armies. Caesar saw this as an attack on his honor and future. He felt he had no choice but to fight to protect his position.

The War Begins

In the months leading up to January 49 BC, both Caesar and Pompey hoped the other would back down. But trust between them was gone.

On January 1, 49 BC, Caesar offered to resign his command if Pompey did the same. But he insisted that their armies should be equal in strength. The Senate, however, sided with Pompey. On January 7, they ordered Caesar to give up his command or be declared an enemy of the state. Some officials who supported Caesar fled Rome to join him.

Crossing the Rubicon

On January 10 or 11, Caesar made a famous decision. He led his army across the Rubicon river. This small river was the boundary between Caesar's province and Italy itself. Crossing it with an army was an act of war against Rome.

When he crossed, Caesar is said to have declared, "Alea iacta est" (meaning "the die is cast"). This meant he had made his decision, and there was no turning back. By crossing the Rubicon, Caesar officially became a rebel against the Roman Republic.

Many Romans found it hard to choose sides. Some soldiers followed Caesar because he was their leader and had treated them well. Others followed Pompey and the consuls because they represented the official Roman government. Even Caesar's trusted general, Titus Labienus, left him to join Pompey.

March on Rome

Italy was not ready for Caesar's invasion. Caesar quickly captured several cities without much fighting. News of his advance reached Rome, causing panic. Pompey and many senators left Rome, fearing Caesar's arrival. They remembered the bloody civil wars of the past.

Caesar tried to negotiate with Pompey, but they couldn't agree. Caesar continued to advance through Italy. His soldiers were disciplined and did not loot cities, which helped prevent the local people from turning against him.

When Caesar reached Corfinium, he faced some resistance. But the Pompeian commander's own soldiers arrested him and surrendered to Caesar. Caesar showed mercy to the captured senators and soldiers, letting them go free. This was different from past civil wars, where enemies were often killed. This policy of mercy helped Caesar gain support.

Pompey decided to leave Italy and escape to Greece. He planned to gather a large army from the eastern provinces of the Roman Republic. Caesar pursued him to Brindisi (Brundisium), but Pompey managed to sail away with most of his forces.

Fighting in Spain and Africa

After Pompey escaped, Caesar went west to Spain. Before leaving Rome, he took money from the state treasury, even though a tribune tried to stop him. This showed that Caesar was willing to break rules to get what he needed.

In Spain, Caesar defeated Pompey's armies at Ilerda. This put all of Spain under his control. Meanwhile, Caesar sent another general, Curio, to invade Africa. But Curio's forces were defeated, and he was killed in battle.

Back in Rome, Caesar was made Roman dictator for a short time. This gave him special powers. He used these powers to hold elections and pass some laws. After just eleven days, he resigned the dictatorship and became a consul again. Then, he continued his pursuit of Pompey.

Battles in Greece

Caesar sailed across the Adriatic Sea to Greece to face Pompey. He didn't have enough ships to transport all his troops at once. Pompey's fleet tried to stop him, but Caesar managed to land some of his forces.

Caesar tried to besiege Pompey's main supply base at Dyrrachium. After months of fighting and skirmishes, Pompey managed to break through Caesar's lines, forcing Caesar to retreat.

Pompey, urged by his allies, decided to fight Caesar in a decisive battle. In August 48 BC, the two massive armies met at the Battle of Pharsalus. Caesar's experienced soldiers fought bravely. A clever move by Caesar's cavalry led to the collapse of Pompey's army. Caesar won a huge victory.

After the defeat, Pompey fled to Egypt. Many of his supporters surrendered to Caesar, who again showed mercy and pardoned them.

Events in Egypt

When Pompey arrived in Egypt, he was murdered by officials of the young King Ptolemy XIII. They hoped to please Caesar. Caesar arrived in Egypt three days later and was reportedly saddened by Pompey's death.

Egypt was in the middle of its own civil war between King Ptolemy XIII and his sister, Cleopatra. Caesar got involved, partly because Egypt owed Rome a lot of money. He also decided to settle the dispute between the royal siblings.

Caesar sided with Cleopatra. She secretly met him and became his ally. Ptolemy XIII's supporters then besieged Caesar in the royal palace in Alexandria. Caesar's forces were eventually rescued by reinforcements. Ptolemy XIII was defeated and drowned.

After his victory, Caesar made Cleopatra and her younger brother co-rulers of Egypt. He stayed in Egypt for several months, making sure Cleopatra's rule was secure. It's believed that Cleopatra had a son, Caesarion, who was likely Caesar's child.

War in Asia Minor

While Caesar was in Egypt, a king named Pharnaces II of Pontus tried to reclaim lands his father had lost to Rome. He invaded parts of Asia Minor.

Caesar quickly moved from Egypt to deal with Pharnaces. He rejected any negotiations and demanded that Pharnaces leave all Roman territory. Caesar's victory was swift and decisive at the Battle of Zela. The entire campaign took only a few weeks.

After this quick win, Caesar famously wrote, "Veni, vidi, vici" ("I came, I saw, I conquered"). This showed how easily he defeated Pharnaces.

Return to Rome and Mutiny

After his campaigns in Egypt and Asia Minor, Caesar returned to Rome in late 47 BC. He pardoned many of his former enemies, including Cicero.

However, some of Caesar's own veteran soldiers in Italy mutinied. They were tired of fighting and wanted their rewards. Caesar met them in person and, by addressing them as "citizens" and offering them immediate discharge and rewards, he shamed them into begging to be taken back into service. He agreed, but made a note of the mutiny's leaders.

Caesar also dealt with financial issues in Rome. He sold the properties of his dead opponents to raise money. He became consul again with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus as his partner.

Final Battles in Africa and Spain

African Campaign

Some of Pompey's remaining supporters, including Cato the Younger and Metellus Scipio, had gathered a new army in Africa (modern-day Tunisia). They were joined by King Juba I of Numidia and his war elephants.

Caesar sailed to Africa in late 47 BC. His forces were initially outnumbered. He faced a tough fight against Labienus and Metellus Scipio. Luckily for Caesar, King Juba had to send some of his forces away to defend his own kingdom from an invasion.

Caesar eventually received more troops and supplies. He then marched to besiege the city of Thapsus. This forced the Pompeian army to fight him in a major battle.

Battle of Thapsus

At the Battle of Thapsus in 46 BC, Caesar's army won a crushing victory. His soldiers attacked spontaneously and routed the Pompeian forces. Thousands of Pompeian soldiers were killed, while Caesar's losses were very small.

After the defeat, Cato the Younger, who was in the city of Utica, took his own life rather than surrender to Caesar. Metellus Scipio also died shortly after the battle. Labienus managed to escape to Spain. Caesar stayed in Africa for a while to settle affairs before returning to Rome.

Second Spanish Campaign

Even after the victory in Africa, the civil war wasn't completely over. Pompey's sons, Gnaeus Pompey and Sextus Pompey, had gathered a large army in Spain. Many of Caesar's former enemies and even some of his own troops had joined them.

Caesar left Rome in November 46 BC to deal with this last threat. He had to fight hard against the Pompeian forces, who were strong and determined. The fighting in Spain was very brutal.

Battle of Munda

The final major battle of the civil war took place at Munda in Spain in March 45 BC. It was a very fierce and close fight. Caesar's army struggled, and he had to personally rally his troops on the front lines.

Eventually, Caesar's Tenth Legion broke through the enemy lines. This led to a complete rout of the Pompeian army. Labienus was killed in the battle. Gnaeus Pompey escaped but was later captured and executed. Sextus Pompey managed to flee and hide.

The Battle of Munda was the final victory for Caesar. The civil war was finally over.

Aftermath

After his victory, Caesar returned to Rome. He celebrated four magnificent parades (triumphs) to honor his victories in Gaul, Egypt, Asia, and Africa. He gave huge bonuses to his soldiers and held massive games and banquets for the public.

The Senate, now eager to please Caesar, gave him many honors. They renamed the month of his birth, Quinctilis, to July in his honor. He was also given the title "father of his country." Most importantly, he was made Roman dictator for life (dictator perpetuo).

Caesar's immense power and his permanent dictatorship worried many senators. They feared he would become a king and destroy the Roman Republic. This led to a conspiracy against him. In March 44 BC, a group of senators, including Marcus Junius Brutus (whom Caesar had pardoned), assassinated Julius Caesar.

Caesar's civil war was a turning point in Roman history. It severely weakened the Roman Republic and its traditional government. After Caesar's death, there was a power vacuum, leading to more civil wars. Eventually, Caesar's adopted son, Octavian, took complete control and established the Roman Empire, ending the Republic for good.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |