Crisis of the Roman Republic facts for kids

The crisis of the Roman Republic was a long time of big problems in ancient Rome. It lasted from around 133 BC to 44 BC. During this period, the Roman Republic fell apart, and the Roman Empire began.

Many things caused this crisis. These included different forms of slavery, groups of bandits, wars both inside and outside Rome, and a lot of corruption. There were also issues with land ownership, new harsh punishments, and the way Roman citizenship was given out. Even the makeup of the Roman army changed, adding to the problems.

Historians today have different ideas about what caused the crisis. Some believe that giving more people citizenship caused arguments and slave revolts. Others argue that the Republic was meant to be for "the people," so poor citizens were right to try and fix their problems.

Contents

What Was the Roman Republic Crisis?

Historians often debate if there was one big crisis or many smaller ones. Some think there were several "republics" over time, each with its own challenges. They see it as a series of problems and changes, rather than one long crisis that destroyed Rome.

This idea suggests that the Republic's fall happened because its political culture changed. Key events were Sulla's civil war and then Caesar's civil war, which ended Sulla's own version of the Republic.

When Did the Roman Crisis Start?

For many years, historians have argued about when the crisis of the Roman Republic truly began and ended. Some say the Romans lost their freedom because their many conquests changed their values.

Early Problems (around 134 to 73 BC)

Many historians point to 133 BC as the start of the crisis. This was when Tiberius Gracchus became a tribune (a powerful official). He suggested a new law to share land more fairly.

When Gracchus tried to be re-elected as tribune, riots broke out. He was killed in 133 BC. This event is often called a "turning point" for the Roman Republic. One writer, Velleius, said this was the start of "civil bloodshed" and when "justice was overthrown by force."

Some historians, like Nic Fields, think the crisis began even earlier, in 135 BC. This was when the First Servile War (a slave rebellion) started in Sicily. Fields notes that other slave revolts happened before Spartacus's famous rebellion.

Things got much worse with the Social War (91–87 BC). In this war, Rome's Italian allies fought against Rome itself. This was a huge civil war. Another low point was the Battle of the Colline Gate (82 BC), which was the final battle between Sulla and Gaius Marius's supporters.

Barry Strauss believes the crisis really started with "The Spartacus War" in 73 BC. He says Rome didn't take the dangers seriously enough at that time.

Later Problems (around 69 to 44 BC)

Other historians, like Ronald Syme, say the crisis truly began with Julius Caesar in 60 BC. Caesar's decision to cross the Rubicon river with his army in 49 BC is a famous moment. This act was against Roman law and showed there was "no turning back" for the Republic.

When Did the Crisis End?

The end of the crisis is also debated. Some say it ended with the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC. He and Sulla had greatly changed the Republic's government.

Others believe the crisis ended in 27 BC. This was when Octavian was given the title of Augustus by the Senate. This event marked the true beginning of the Roman Empire. Some even say it ended earlier, with Caesar's own changes in 49 BC.

Key Events in the Crisis

After the Second Punic War, there was a huge increase in the gap between rich and poor. Many farmers were drafted into the army for long periods. Their farms often failed while they were away. Rome's military victories brought many slaves to Italy, and wealth was not shared equally. The city of Rome grew very rich and large. Many freed slaves also became poor in the cities and countryside.

Rome also stopped creating new colonies in Italy around 177 BC. These colonies had helped poor citizens get land and jobs, and also increased the number of farmers available for the army.

Sulla's Civil War

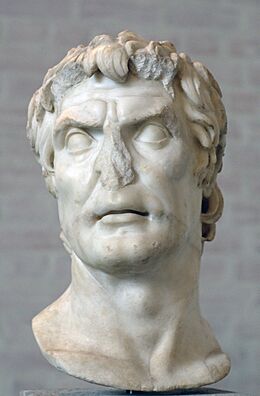

After the Social War (91–87 BC), Rome gave citizenship to almost all Italian communities. The big question was how to include these new citizens in Rome's political system. In 88 BC, a tribune named Publius Sulpicius Rufus tried to pass laws to give Italians more political rights. He also tried to transfer command of a war from Sulla to Gaius Marius.

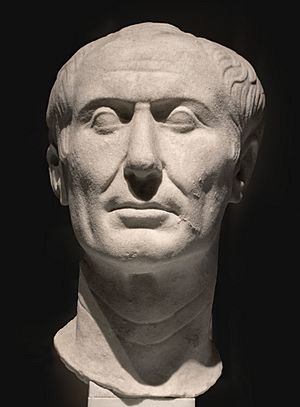

Sulla was very angry about this. He did something no general had done before: he marched his army on Rome. This broke all the rules about using military force. Sulla declared his political enemies outlaws and ordered them killed. Marius escaped, but Sulpicius was killed. Sulla then forced major changes to the constitution before leaving to fight a war in the East.

While Sulla was away, Lucius Cornelius Cinna took control of Rome. He held elections and ran the city. Cinna and his allies hated Sulla. They destroyed Sulla's house and forced his family to flee. Cinna was elected consul three times in a row. He also killed many of his political opponents, putting their heads on display in the forum.

Sulla returned in 82 BC with his army. He had made peace with his enemies in the East. He then fought a civil war to take back Rome from Cinna's group. After winning, Sulla killed thousands of his political enemies, often taking their wealth. He forced the Roman assemblies to make him a dictator with no time limit. He also made laws that stopped the families of those he killed from taking part in politics. Sulla's actions used violence in a new, extreme way. He not only took control but kept it, unlike others before him.

Sulla's dictatorship changed Rome's politics. He removed many senators who believed in making decisions by agreement. Sulla's reforms tried to give more power to the Senate and the wealthy classes. He also tried to reduce the power of the tribunes and the people's assembly. For example, he made it so that all new laws had to be approved by the Senate first. He also made it harder for tribunes to stop laws and prevented them from holding other important offices later. This was meant to stop ambitious young men from becoming tribunes.

Sulla also made the Senate bigger by adding many new members. He created more courts and made the legal system stronger. He hoped this would stop powerful politicians from gaining too much control.

He also set clear rules for the cursus honorum, which was the path of political offices a Roman could hold. He doubled the number of quaestors (financial officials) and added more praetors (judges). This meant officials would serve shorter times in provinces, making it harder for them to build up too much power. He also made it illegal to be re-elected to any office for ten years.

After being elected consul in 80 BC, Sulla gave up his dictatorship. He tried to make his constitutional changes permanent. But Sulla's reforms did not work well. Rome still faced civil war in Spain and a revolt in 78 BC. The powers of the tribunes were quickly restored by 70 BC by Sulla's own former officers, Pompey and Crassus.

Sulla had made it illegal to march on Rome with an army, but he had just shown that if you won, there were no bad consequences. So, his actions weakened the constitution. They set a clear example that a strong general could ignore the rules by using military force. The new, stricter courts Sulla created also caused problems. Commanders would rather start civil wars than face harsh punishments in court. Sulla's example also led many Romans to avoid provincial commands, meaning military experience became concentrated in fewer hands.

The Republic Collapses

As the Republic continued, its important institutions lost their power and respect. For example, Sulla's changes to the Senate created deeper divisions among the wealthy class. Also, the military became very powerful. Soldiers became more loyal to their generals because generals often provided for their retirement. This meant many unhappy soldiers were willing to fight against the state.

Violence became a common way to get political changes or stop them. The deaths of the Gracchi brothers and Sulla's dictatorship showed this. The Republic was caught in a cycle of increasing violence and chaos between the Senate, the assemblies in Rome, and powerful generals.

By the early 60s BC, political violence was back. There were riots during elections every year between 66 and 63 BC. The revolt of Catiline, a famous event, was put down by violating citizens' rights and using the death penalty against them. The chaos after Sulla's reforms had not fixed problems like land reform, the rights of families punished by Sulla, or the strong disagreements between Marius's and Sulla's supporters.

During this time, Pompey gained huge wealth and power from his long military commands in the East. When he returned in 62 BC, the Republic couldn't handle his power. His achievements were not recognized, but he also couldn't be sent away to win more victories. His unique position created a dangerous situation that the Senate and other officials couldn't control. Both Cicero's actions as consul and Pompey's military successes challenged the Republic's laws, which were meant to limit ambition and ensure fair trials.

The state was then controlled by three powerful men: Julius Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey. This group, known as the First Triumvirate, started in 59 BC. They controlled elections, held office often, and broke laws. Their power was so great that other officials were afraid to oppose them.

Political violence grew worse and more chaotic. In the mid-50s BC, street gangs led by Publius Clodius Pulcher and Titus Annius Milo caused total anarchy. They often stopped elections from happening. This continued until Pompey was simply appointed as the only consul by the Senate in 52 BC, without asking the assemblies.

Pompey's control of the city and repeated political problems led Caesar to believe that he would not get a fair trial if he returned to Rome without his army. This started Caesar's civil war.

After Caesar won the civil war, he ruled as a dictator until he was killed in 44 BC by a group called the Liberatores. Caesar's supporters quickly took control. They formed the Second Triumvirate, which included Caesar's adopted son Octavian, Mark Antony, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. They killed their political enemies and defeated Caesar's assassins in the Liberators' civil war.

However, the Second Triumvirate could not agree on how to share power. This led to the final civil war of the Republic. Octavian won this war, and the Republic finally collapsed for good. Octavian, now called Augustus, became the first Roman Emperor. He changed the Republic, which was ruled by a few powerful families, into an autocratic empire, ruled by one person.

|

See also

- Constitutional crisis

- Crisis of the Third Century

- Damnatio memoriae

- Democratic backsliding

- Fall of the Western Roman Empire

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |