European debt crisis facts for kids

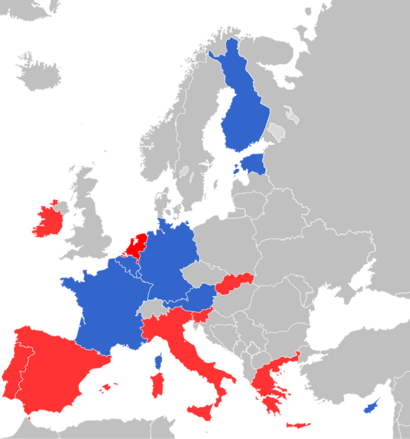

The European debt crisis, also called the eurozone crisis, was a big money problem in the European Union (EU). It lasted from 2009 to the mid-2010s. Several countries that use the euro currency had trouble. These countries were Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Cyprus. They couldn't pay back their government debt or help their struggling banks. They needed help from other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The crisis happened because foreign money suddenly stopped flowing into these countries. They had been borrowing a lot from other countries. The problem got worse because these countries couldn't make their money worth less (called devaluation). This is usually a way to make exports cheaper and boost the economy. But they all used the euro, so they couldn't do it alone.

Before the euro, countries in the eurozone had different economic situations. The ECB set one interest rate for everyone. This made it cheap for southern countries to borrow money. It also encouraged northern countries to lend money to the south. Over time, southern countries borrowed too much, especially private businesses.

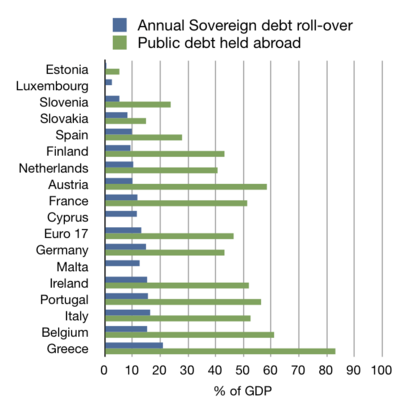

Governments didn't work together enough on money rules. Banks also took big risks because they thought governments would always save them. The exact reasons for the crisis were a bit different for each country. Often, private debts from housing bubbles became government debts when banks needed saving. European banks owned a lot of government debt. So, if banks were in trouble, governments were too, and vice versa.

The crisis started in late 2009. Greece announced its budget problems were much worse than thought. Greece asked for help in early 2010. It got a rescue package from the EU and IMF in May 2010. European nations created special funds like the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). The ECB also helped by lowering interest rates and giving cheap loans to banks.

By September 2012, the ECB promised unlimited support for countries in bailout programs. This helped calm financial markets. Ireland and Portugal got bailouts in late 2010 and mid-2011. Greece got a second bailout in March 2012. Spain and Cyprus also received help in June 2012.

As their economies grew stronger, Ireland and Portugal left their bailout programs in July 2014. Greece and Cyprus also started to borrow money from markets again in 2014. Spain never officially got a full government bailout. Its help was only for its banks. The crisis caused big economic problems. Unemployment reached 27% in Greece and Spain. It also slowed down economic growth across Europe. The crisis even led to new governments in 10 out of 19 eurozone countries.

Contents

Why Did the Crisis Happen?

The eurozone crisis was caused by many things. One main reason was a "balance-of-payments crisis." This means foreign money suddenly stopped flowing into countries that needed to borrow a lot. The problem got worse because countries couldn't make their money worth less (devalue their currency). This would have made their exports cheaper.

Other factors included:

- Banks lending and borrowing too easily before 2008.

- The financial crisis of 2007–08 around the world.

- Countries importing much more than they exported.

- Housing bubbles that burst.

- The Great Recession from 2008 to 2012.

- Government choices about spending and taxes.

- How governments saved troubled banks, taking on their debts.

How Money Flowed Unevenly

Countries in the eurozone had different economic situations. But the European Central Bank (ECB) could only set one interest rate for everyone. This meant that in countries like Germany, borrowing was expensive. In southern countries, it was very cheap. This encouraged German investors to lend money to the south. Southern countries were eager to borrow because it was so cheap. Over time, this led to southern countries, especially private businesses, borrowing too much.

Rules Not Followed

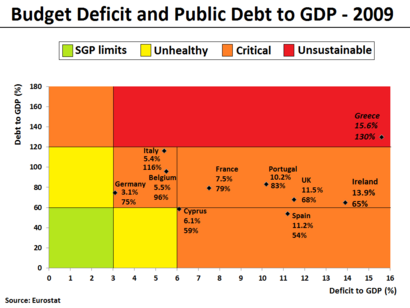

Countries in the eurozone were supposed to limit their spending and debt. This was part of the Maastricht Treaty from 1992. But some countries, like Germany and France, didn't always follow these rules. They used clever accounting tricks to hide their true debt.

In late 2009, Greece admitted its budget problems were much bigger than it had said. This made people worry that some countries might not be able to pay their debts. The crisis then spread to Ireland and Portugal. It also raised concerns about Italy, Spain, and the whole European banking system.

Banks Taking Risks

Rules for banks were different in each country. This allowed banks to take big risks with loans. If rules were the same everywhere, it might have stopped some risky loans. Also, governments couldn't promise they wouldn't save banks that took risks. This meant banks had less reason to be careful.

How the Crisis Unfolded

The European debt crisis started around late 2009, after the Great Recession. Governments had high debts and were spending too much. Many banks in Europe had lost a lot of money. Governments had to save these banks with loans. This was because the banks were so important for the economy. These government bailouts made the countries' own debts much higher.

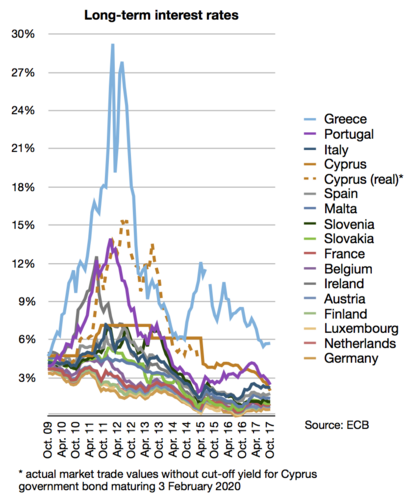

In early 2010, lenders started asking for very high interest rates from countries with high debts. This made it hard for Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain to borrow money or pay back old debts. Especially when their economies weren't growing.

These affected countries saw their borrowing costs go up a lot. Four eurozone countries needed rescue programs. These were provided by the International Monetary Fund and the European Commission. The European Central Bank also helped. These three groups were nicknamed "the Troika".

To fight the crisis, some governments raised taxes and cut spending. This caused protests and debates. Many economists argued that governments should spend more when economies are struggling. Countries like Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, and Finland actually benefited from the crisis. Investors saw them as safe places to put their money. So, these countries could borrow money at very low interest rates.

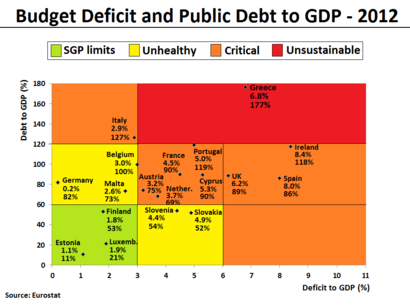

Even though only a few countries had very high debts, it became a problem for the whole euro area. People worried the crisis might spread. By the end of 2012, five out of 17 eurozone countries had to ask for help.

By mid-2012, things started to get better. Countries made reforms, and EU leaders and the ECB took action. Interest rates fell, and the risk of the crisis spreading went down. By early 2013, countries like Ireland, Spain, and Portugal were able to borrow money from markets again. By May 2014, only Greece and Cyprus still needed outside help.

Greece's Debt Story

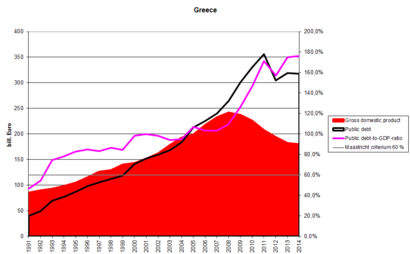

Greece's economy was doing well for most of the 20th century. But by 2007, its main industries, shipping and tourism, were hit hard by the global financial crisis. The government spent a lot to keep the economy going, and its debt grew.

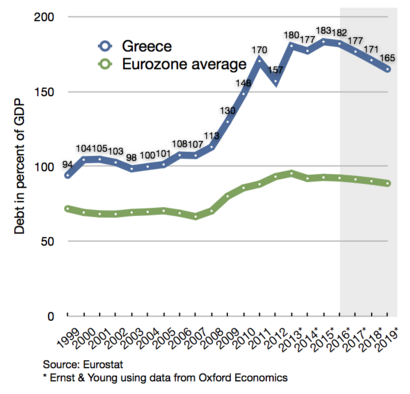

The Greek crisis started when its budget problems became clear. Its debt was already high. As a member of the eurozone, Greece couldn't print more money or make its currency cheaper to help itself.

In April 2010, Greece couldn't borrow from markets anymore. It asked the EU and IMF for a €45 billion loan. A few days later, a rating agency lowered Greece's debt rating to "junk status." This meant investors thought it was very risky to lend to Greece. Stock markets and the euro currency fell.

On May 1, 2010, Greece announced harsh cuts to spending (austerity measures) to get a €110 billion loan. This led to huge protests and riots in Greece. The "Troika" (European Commission, ECB, and IMF) offered a second bailout of €130 billion in October 2011. But Greece had to make more cuts and change its debt. The Greek Prime Minister, George Papandreou, first wanted a public vote on the bailout. But he backed down under pressure from EU partners.

The spending cuts helped Greece reduce its budget deficit. But they also made the recession worse. Greece's economy shrank a lot in 2011. Many companies went bankrupt. Greeks lost about 40% of their buying power. Unemployment rose from 7.5% in 2008 to almost 28% in 2013. Youth unemployment was even higher.

Some experts thought Greece should leave the euro and bring back its old currency, the drachma. They believed this would help the economy. But others warned it would be disastrous, leading to huge currency drops and very high prices.

To prevent this, the Troika agreed to a second bailout in February 2012. This was worth €130 billion. It required more harsh spending cuts. In March 2012, Greece did something unusual. It made private lenders accept a big cut in the value of their Greek government bonds. This was the biggest debt restructuring ever. It reduced Greece's debt by €107 billion.

Critics said the bailouts mostly helped European banks, not Greece. They argued that most of the money went to pay off old Greek debt held by private banks, mainly in France and Germany.

In mid-2012, there were worries Greece might leave the eurozone (called "Grexit"). But a new government was formed that wanted to stay. Greece's economy started to improve in 2014. It even started borrowing from bond markets again. The Greek government debt crisis officially ended in 2015. However, some problems, like high unemployment, continued for years.

In 2015, Greece's citizens voted against more bailout help with more cuts. Greece became the first developed country to miss a payment to the IMF. Eventually, Greece agreed to a third bailout package in August 2015.

Between 2009 and 2017, Greece's government debt didn't grow much. But its debt-to-GDP ratio (debt compared to economic output) shot up. This was because its economy shrank so much during the crisis. Greece's bailouts officially ended on August 20, 2018.

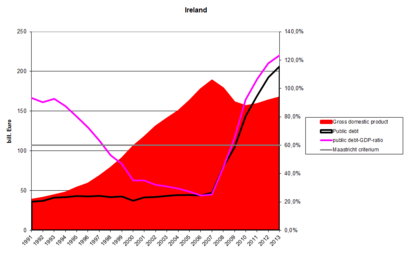

Ireland's Bank Troubles

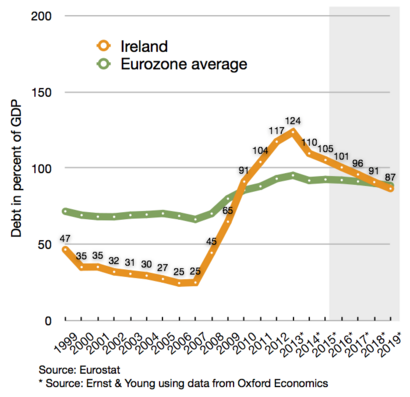

Ireland's debt crisis wasn't caused by the government spending too much. It happened because the government promised to protect six major Irish banks. These banks had lent too much money for a property bubble that burst around 2007.

Irish banks lost about €100 billion. The economy collapsed in 2008. Unemployment jumped from 4% in 2006 to 14% by 2010. The national budget went from having extra money in 2007 to a huge deficit of 32% of GDP in 2010. This was the highest in eurozone history.

As Ireland's credit rating fell, people who had lent money to Irish banks started taking their money out. In November 2010, Ireland had to ask the EU and IMF for a €67.5 billion bailout. Part of this money was used to help the failing banks. In return, Ireland agreed to cut its budget deficit.

In July 2011, European leaders agreed to lower the interest rate on Ireland's bailout loan. This saved the country hundreds of millions of euros each year. Ireland made good progress in fixing its financial problems. By 2013, the cost of borrowing for the Irish government had fallen a lot.

In December 2013, Ireland successfully left the EU/IMF bailout program. It didn't need any more financial help. However, unemployment remained high, and public sector wages were still lower than before the crisis.

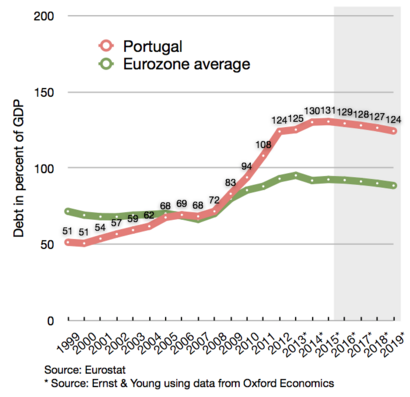

Portugal's Economic Struggles

Unlike Greece and Ireland, Portugal's economy wasn't growing much even before the crisis. It had already faced economic problems and tried to cut spending. Reports showed that Portugal had wasted a lot of money on public projects and high salaries for government officials for decades. When the global crisis hit, Portugal was deeply affected.

In mid-2010, a rating agency lowered Portugal's government bond rating. This made it harder and more expensive for Portugal to borrow money. In early 2011, Portugal asked for a €78 billion IMF-EU bailout.

The Troika predicted Portugal's debt would peak around 124% of GDP in 2014. Portugal was given an extra year to reduce its budget deficit. The economy was expected to shrink until 2013. Unemployment rose to over 17% by the end of 2012, but has since decreased.

As part of the bailout, Portugal had to regain full access to financial markets by September 2013. It started borrowing money again in October 2012. By May 2013, it was able to sell long-term bonds again.

Portugal left the EU bailout program on May 18, 2014, without needing more support. It had already regained full access to lending markets. However, Portugal still faced challenges. Its government debt increased significantly during the crisis. In August 2014, Portugal's second-biggest bank had to be split in two after losing a lot of money.

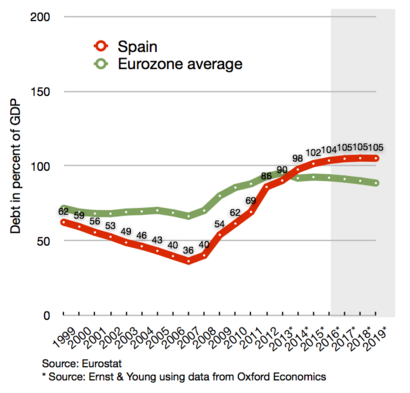

Spain's Housing Bubble Burst

Spain had low debt before the crisis. Its government debt was much lower than Germany's or France's. This was because a booming housing market brought in a lot of tax money. But when the housing bubble burst, Spain spent huge amounts of money saving its banks. For example, Bankia received a €19 billion bailout in May 2012.

The bank bailouts and the economic slowdown increased Spain's debt. Its credit rating was lowered. To regain trust, the government started cutting spending. In 2011, Spain even changed its constitution to require a balanced budget by 2020.

In June 2012, Spain became a big concern for the eurozone. The interest rate on its 10-year bonds reached 7%. This made it hard to borrow money. The Eurogroup agreed to give Spain up to €100 billion. This money went directly to a Spanish fund to recapitalize banks, not to the government itself. So, Spain technically didn't have a "sovereign debt crisis" in the same way as Greece.

The European Commission predicted Spain's debt-to-GDP ratio would peak at 110% in 2018. Spain was suffering from 27% unemployment in 2013. But the government promised to speed up reforms.

On January 23, 2014, Spain officially left the EU/IMF bailout program. Foreign investors trusted the country again. By March 2018, Spain's unemployment rate had fallen to 16.1%.

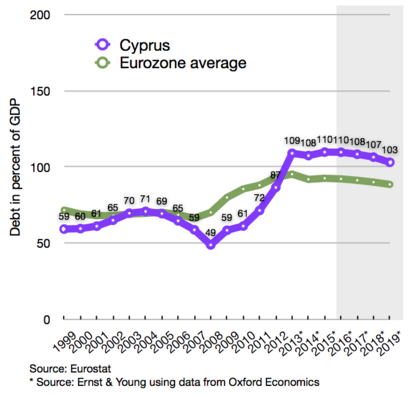

Cyprus's Banking Woes

The small island economy of Cyprus was hit hard around 2012. Cypriot banks had lent a lot of money to Greece. When Greece restructured its debt, Cypriot banks lost €22 billion. International rating agencies lowered Cyprus's economy to "junk status." The government couldn't pay its expenses.

On June 25, 2012, Cyprus asked for a bailout. It needed help for its banking sector. In November, the Troika and Cyprus agreed on bailout terms. These included harsh spending cuts and tax increases. At first, they even suggested taking money directly from bank accounts. This caused a huge public outcry.

The final agreement was reached on March 25, 2013. It involved closing the most troubled bank, Laiki Bank. This reduced the amount of money needed for the bailout to €10 billion. The conditions for the bailout included:

- Fixing the financial sector and closing Laiki Bank.

- Improving rules against money laundering.

- Cutting government spending to reduce the budget deficit.

- Making economic changes to become more competitive.

- Selling off state-owned companies.

Cyprus's debt-to-GDP ratio was expected to peak at 126% in 2015. Cyprus slowly started to borrow money from private markets again in June 2014. By April 2015, the government successfully issued €1 billion in bonds.

How Europe Responded

Europe took several steps to deal with the crisis.

EU Emergency Measures

European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF)

In May 2010, the 27 EU countries created the EFSF. This was a way to keep Europe's finances stable. It could give loans to eurozone countries in trouble, help banks, or buy government debt. The EFSF got money by selling bonds, backed by guarantees from eurozone countries. It could lend up to €440 billion. It also worked with the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM) and the IMF.

European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM)

In January 2011, the EU created the EFSM. This was another emergency fund. It raised money by selling bonds, backed by the EU's budget. It could raise up to €60 billion. The EFSM helped countries like Ireland. Both the EFSF and EFSM were later replaced by a permanent fund called the ESM.

Brussels Agreement

In October 2011, eurozone leaders met in Brussels. They agreed to a 50% cut in Greek debt held by banks. They also agreed to increase bailout funds to about €1 trillion. Banks in the EU had to hold more capital. Italy also promised to reduce its debt.

European Central Bank (ECB) Actions

The ECB took many steps to calm financial markets and make sure banks had enough money.

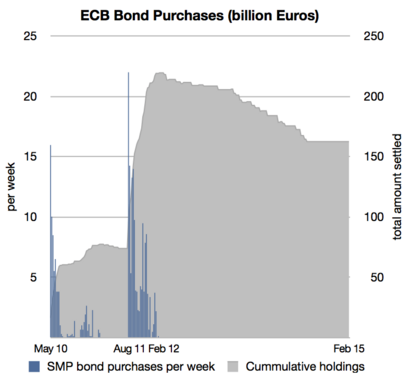

- It started buying government and private debt.

- It made it easier for banks to get dollars.

- It accepted Greek government debt as collateral for loans, even if its rating was low.

In November 2011, the ECB and other major central banks (US, Canada, Japan, UK, Switzerland) worked together. They lowered the cost of getting dollars for banks. This helped prevent a money shortage.

The ECB also lowered its main interest rate many times in 2012-2013, reaching a very low 0.25% in November 2013. This aimed to make it cheaper for businesses to borrow and boost the economy. Lower rates also made the euro weaker, which helps exports.

In June 2014, with very low inflation, the ECB cut its prime interest rate to 0.15%. It even set the deposit rate at -0.10%. This meant banks had to pay to keep money at the ECB. This was a bold move, never tried widely before. The ECB also offered long-term loans to banks, but only if they lent the money to businesses. These steps aimed to avoid falling prices (deflation), make exports cheaper, and increase lending.

Stock markets reacted strongly to the ECB's rate cuts. The head of the ECB, Mario Draghi, said the bank would do "whatever it takes" to fix the eurozone economy.

Long Term Refinancing Operation (LTRO)

In December 2011, the ECB gave a huge amount of cheap loans to European banks. It loaned €489 billion to 523 banks for three years at just 1% interest. This was to make sure banks had enough cash to pay their own debts and keep lending to businesses. It also hoped banks would use some money to buy government bonds, helping the debt crisis. In February 2012, the ECB held a second, even bigger auction, lending another €529.5 billion.

Outright Monetary Transactions (OMTs)

In September 2012, the ECB announced it would buy government bonds from countries in bailout programs. This would help lower their borrowing costs. This plan helped calm markets, even before any bonds were actually bought.

European Stability Mechanism (ESM)

The ESM is a permanent rescue fund. It replaced the EFSF and EFSM in September 2012. It acts as a "financial firewall." This means if one country defaults on its debt, the ESM can protect other countries and banks from the problem spreading.

European Fiscal Compact

In March 2011, rules for government spending were made stricter. By the end of 2011, 26 EU countries agreed to a new treaty. This treaty put strict limits on government spending and borrowing. Countries that broke the rules would face penalties. This was meant to create a "fiscal union" with stronger financial rules.

Ideas for Fixing Things Long-Term

To make the euro area strong for the future, countries need to make big changes. They need to make it easier for people to move for jobs and for wages to change more easily. This will help southern economies become more competitive.

Direct Loans to Banks

In June 2012, eurozone leaders agreed that the ESM could lend money directly to struggling banks. This was important because it meant the loans wouldn't add to the country's government debt. This reform was linked to plans for the ECB to become a bank regulator.

Less Austerity, More Investment

Many experts criticized the harsh spending cuts (austerity) in Europe. They argued that these cuts made recessions longer and deeper. They believed that cutting spending during a crisis makes people save more, which means less demand for goods and jobs. This makes the recession worse.

Instead of just cutting, some suggested a "growth compact." This would involve more government spending and investments, paid for by taxes on things like property and pollution. They also suggested giving more money to the European Investment Bank (EIB) to lend to businesses.

Many EU countries have focused on cutting budget deficits and making their economies more competitive. The "Euro Plus Pact" and "Fiscal Compact" are agreements for political and financial reforms. Countries in bailout programs also had to make their economies more competitive by lowering production costs.

Increase Competitiveness

Countries in crisis need to become much more competitive to grow their economies. Usually, a country can make its currency cheaper to do this. But eurozone countries can't devalue their currency.

Internal Devaluation

As a workaround, many countries tried "internal devaluation." This means reducing the cost of labor. For example, wages in Greece were cut to levels last seen in the late 1990s. This was very painful for people. Some economists argue that no matter how much wages are cut, these countries can't compete with very low-cost countries like China. Instead, they should focus on making higher-quality products and services.

Fiscal Devaluation

Another idea is "fiscal devaluation." This means lowering taxes for businesses (like social security payments) and making up the lost money by raising taxes on consumption (like VAT) or pollution. Germany has done this successfully. Portugal and France have also tried similar approaches.

Address Trade Imbalances

Some countries, like Germany, export much more than they import. Other countries, like Greece, import much more than they export. This creates imbalances. A country that imports more than it exports must borrow money to pay for those imports.

Since eurozone countries can't change their currency value or interest rates individually, the only way to fix these imbalances is for countries that import a lot to consume less and export more. Countries that export a lot, like Germany, might need to encourage more domestic spending.

Some economists believe the crisis was more about these trade imbalances than just government debt.

Eurobonds

Many investors and economists suggested "eurobonds" as a solution. These would be bonds issued jointly by all eurozone countries. This would make borrowing cheaper for struggling countries. But Germany was largely against this, at least in the short term. It worried about taking on the debt of countries that had spent too much.

European Safe Bonds (ESBies)

A new idea is "European Safe Bonds" (ESBies). These would be bundles of government bonds from different European countries. They would be designed to be very safe, like German bonds, but without countries being fully responsible for each other's debts. This idea has gained interest from the ECB and European Commission.

European Monetary Fund (EMF)

Another idea is to turn the ESM into a "European Monetary Fund" (EMF). This EMF could give governments loans at fixed, low interest rates. These loans would be backed by all eurozone countries and the ECB. To ensure countries were careful with money, the EMF would only lend to countries that met strict financial rules. Countries that didn't follow the rules would have to borrow from regular markets at higher rates.

Debt Write-off Financed by Wealth Tax

Some experts suggested that to fix the huge debt problem, a one-time tax on wealth might be needed. This would be a tax on people's assets, like property and investments. They argued that waiting longer would only make such a step more necessary. For example, the economist Thomas Piketty suggested a 15% flat tax on private wealth could pay off a year's worth of national income.

Others suggested a long-term debt-reduction plan, similar to what Germany used after World War II.

Political Impact

The crisis led to many governments in Europe losing power or early elections:

- Ireland (February 2011): The government collapsed after a huge budget deficit and bailout worries.

- Portugal (March 2011): The Prime Minister resigned after parliament didn't approve spending cuts.

- Spain (July 2011): The Prime Minister called early elections because of the economic situation.

- Slovenia (September 2011): The government lost a vote of confidence after referendums on crisis measures failed.

- Slovakia (October 2011): The Prime Minister had to call early elections to get bailout fund approval.

- Italy (November 2011): The Prime Minister resigned due to market pressure on government debt.

- Greece (November 2011): The Prime Minister resigned after facing strong criticism for suggesting a public vote on bailout measures.

- Netherlands (April 2012): The government collapsed after talks on a new austerity package failed.

- France (May 2012): The President lost his re-election bid, partly due to the economic situation.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |