Anthony Blunt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Anthony Blunt |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Allegiance | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Birth name | Anthony Frederick Blunt |

| Born | 26 September 1907 Bournemouth, Hampshire, England |

| Died | 26 March 1983 (aged 75) Westminster, London, England |

| Buried | Putney Vale Cemetery and Crematorium, London, England |

| Occupation | Art historian, professor, writer, spy |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

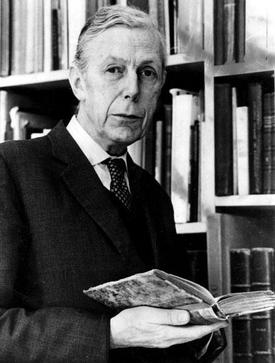

Anthony Frederick Blunt (born September 26, 1907 – died March 26, 1983) was a famous British art historian. He was also a secret agent for the Soviet Union. From 1956 to 1979, he was known as Sir Anthony Blunt.

Blunt taught art history at the University of London. He was also the director of the Courtauld Institute of Art. He held an important job as the Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures. This meant he was in charge of the royal art collection.

His book about the French painter Nicolas Poussin is still very important in art history. Another book, Art and Architecture in France 1500–1700, is still seen as the best book on the topic.

In 1964, Blunt admitted he had been a spy for the Soviet Union. He was given a promise that he would not be punished if he told the truth. He was known as the "fourth man" of the Cambridge Five. This was a group of spies who went to Cambridge University. They worked for the Soviet Union from the 1930s to the early 1950s.

Blunt did most of his spying during World War II. He gave the Soviets information about German army plans. The British government had decided not to share this information with their ally, the Soviet Union. His confession was kept secret for many years. But in November 1979, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher told the public. After this, he lost his special title of "Sir".

Contents

Growing Up and Education

Anthony Blunt was born in Bournemouth, England, on September 26, 1907. He was the youngest of three sons. His father was a vicar, a type of priest.

When Anthony was a child, his family lived in Paris, France, for several years. His father worked at the British embassy chapel there. Living in Paris helped Anthony learn French very well. It also made him love art, which became his life's work.

He went to Marlborough College, a private school for boys. At Marlborough, he joined a secret group called the 'Society of Amici'. Famous writers like Louis MacNeice and John Betjeman were also in this group.

In 1928, Blunt started a political magazine called Venture. It featured articles by writers who had left-wing ideas.

Time at Cambridge University

Blunt won a scholarship to study mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge. He later changed his studies to Modern Languages. He graduated in 1930 with top honors.

After graduating, he taught French at Cambridge. In 1932, he became a Fellow of Trinity College. This meant he was a senior member of the college. He also studied French art history and often traveled to Europe for his research.

Becoming a Spy

There are different stories about how Anthony Blunt became a spy for the Soviet Union. He visited the Soviet Union in 1933. Some believe he was recruited as a spy in 1934.

Blunt himself said that Guy Burgess recruited him. Burgess was a friend from Cambridge. In 1937, Burgess introduced Blunt to a Soviet recruiter named Arnold Deutsch. Blunt then became a "talent spotter" for the Soviets. This meant he looked for other people who might want to spy for them.

Blunt might have suggested his friends Guy Burgess, Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, John Cairncross, and Michael Straight as possible spies. All of them were students at Cambridge University.

Working for British Intelligence

In 1939, when World War II started, Blunt joined the British Army. He worked in the Intelligence Corps in France. In May 1940, he was part of the Dunkirk evacuation, where British soldiers were rescued from France.

Later that year, he joined MI5, which is Britain's security service. While at MI5, Blunt started passing secret information to the Soviets. This included details from "Ultra" intelligence. Ultra was information gathered by decoding German messages from their Enigma machines. This information was about German army plans on the Eastern Front.

It was very risky to share this information. If the Germans found out their codes were broken, they would change them. This would make it impossible to read their messages. Only a few people knew the full details of Operation Ultra.

John Cairncross, another Cambridge spy, worked at Bletchley Park, where the codes were broken. Blunt admitted to recruiting Cairncross. He might have been the secret link between Cairncross and the Soviet contacts. Even though the Soviet Union was an ally, the British did not fully trust them.

Some of the information shared concerned German plans for the Battle of Kursk. This was a very important battle on the Eastern Front. Blunt reached the rank of major during the war. After the war, his spying slowed down. But he still kept in touch with Soviet agents. He also passed them documents from his friend Guy Burgess. This continued until Burgess and Maclean left Britain in 1951.

Trips for the Royal Family

In April 1945, Blunt was offered an important job. He became the Surveyor of the King's Pictures. This meant he was in charge of the art collection for the King. He had worked part-time at the Royal Library before this.

The Royal Librarian, Owen Morshead, suggested Blunt for the job. Morshead was impressed by Blunt's hard work and good manners. The royal family liked Blunt because he was polite and kept secrets well.

At the end of World War II in Europe, King George VI asked Blunt to go on a trip. In August 1945, Blunt went with Morshead to Germany. Their job was to get back nearly 4,000 letters. These letters were written by Queen Victoria to her daughter, Empress Victoria. The letters were at risk because of the unsettled conditions after the war. Blunt knew German, which helped them find the right documents.

Blunt made three more trips over the next year and a half. He mainly went to get back royal treasures that the Crown did not automatically own. On one trip, he returned with an old book with beautiful pictures. He also brought back the diamond crown of Queen Charlotte.

Secret Confession

Some people knew about Blunt's spying long before it became public. In 1950, someone reported that Blunt was a member of the Communist Party. But this was not acted upon. Blunt was even friends with Sir Dick White, who was the head of MI5.

After Burgess and Maclean left Britain for Moscow in May 1951, Blunt came under suspicion. He and Burgess had been friends since their time at Cambridge. Blunt was questioned by MI5 in 1952. But he did not admit anything at that time.

In 1963, MI5 learned about Blunt's spying from an American named Michael Straight. Blunt had recruited Straight as a spy. Blunt confessed to MI5 on April 23, 1964. Queen Elizabeth II was told about it soon after. He also named other people who had been spies.

Blunt thought his confession would be kept secret. He believed the security service would keep it private. In return for his full confession, the British government agreed not to punish him. They also promised to keep his spying a secret for fifteen years. Blunt did not lose his knighthood until 1979, when the Prime Minister announced his betrayal.

For unknown reasons, the Prime Minister at the time, Alec Douglas-Home, was not told about Blunt's spying. But the Queen and the Home Secretary were fully informed. In November 1979, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher officially told the public about Blunt's spying. She also explained the deal that had been made.

Public Exposure

In 1979, a book by Andrew Boyle called Climate of Treason was published. It talked about Blunt's role as a spy but used a fake name for him. Blunt tried to stop the book from being published. This drew attention to him.

In early November, parts of the book were published in a newspaper. On November 8, a magazine revealed that the spy in the book was Anthony Blunt. The Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, was very upset by this. She felt that the secret deal was wrong.

On November 20, Blunt told the news media that the decision to give him immunity was made by the former Prime Minister. The next day, Margaret Thatcher shared more details in the House of Commons.

For weeks after Thatcher's announcement, reporters followed Blunt everywhere. He was surrounded by photographers. Blunt seemed calm on the outside. But the sudden public exposure was a shock. His friend, Brian Sewell, helped protect him from the media.

In 1979, Blunt said his reason for betraying Britain was based on a famous idea. It was from the writer E. M. Forster. Forster believed that if you had to choose between betraying a friend and betraying your country, you should betray your country. However, many people disagreed with Blunt's view.

Queen Elizabeth II took away Blunt's knighthood. He also lost his honorary position at Trinity College. Blunt resigned from the British Academy. He cried during his confession on BBC Television when he was 72 years old.

Anthony Blunt died from a heart attack in London in 1983, at the age of 75.

Memoirs

After he was publicly exposed, Blunt stayed away from society. But he continued his work on art history. His friend Tess Rothschild suggested he write his life story.

Blunt stopped writing in 1983. He left his unfinished memoirs to his partner, John Gaskin. Gaskin later gave them to Blunt's executor, John Golding. Golding gave them to the British Library. He asked that they not be released for 25 years. They were finally made public on July 23, 2009.

In his memoirs, Blunt admitted that spying for the Soviet Union was the biggest mistake of his life. However, he did not apologize for his actions.

Career as an Art Historian

Even while he was spying, Blunt had a very successful public career as an art historian. In 1940, his important paper Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450–1600 was published. It is still in print today.

In 1945, he became the Surveyor of the King's Pictures. After King George VI died in 1952, he became the Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures. He was in charge of the Royal Collection, which is one of the world's largest art collections. He held this job for 27 years. In 1956, he was knighted for his work in this role. He helped expand the Queen's Gallery at Buckingham Palace, which opened in 1962. He also helped organize the cataloging of the collection.

University and Institute Work

In 1947, Blunt became a Professor of the History of Art at the University of London. He also became the director of the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London. He had been lecturing there since 1933. He was director until 1974.

During his 27 years at the Courtauld Institute, Blunt was known as a dedicated teacher. He was also a kind boss to his staff. He helped the Courtauld grow. He brought in more staff, more money, and more space. He also helped the Courtauld's Galleries get amazing art collections. Many people say he made the Courtauld what it is today. He also helped start the study of art history in Britain. He trained many future British art historians.

Research and Books

In 1953, Blunt published his book Art and Architecture in France, 1500–1700. He was especially an expert on the works of Nicolas Poussin. He wrote many books and articles about Poussin. He also helped organize a very successful Poussin exhibition at the Louvre museum in 1960.

He wrote about many different topics. These included William Blake and Pablo Picasso. He also wrote about art galleries in England, Scotland, and Wales. He cataloged many drawings in the Royal Collection.

In 1965, Blunt became very interested in Sicilian Baroque architecture. In 1968, he wrote an important book called Sicilian Baroque.

After Margaret Thatcher revealed his spying, Blunt continued his art history work. He wrote and published a Guide to Baroque Rome in 1982. He had planned to write a book about the architecture of Pietro da Cortona. But he died before he could finish it. His notes were used by another art historian, Jörg Martin Merz. Merz published a book in 2008 that included Blunt's work.

Many of Blunt's books are still important for studying art history today. His writing is clear. He explains art and architecture by placing them in their historical context. For example, in Art and Architecture in France, he describes the social, political, and religious situations. These situations influenced how art and art movements developed.

Famous Students

Many notable students were taught by Anthony Blunt. These include:

- Aaron Scharf, a photography historian.

- Brian Sewell, an art critic.

- Sir Oliver Millar, who took over Blunt's job at the Royal Collection.

- Nicholas Serota, a former director of the Tate Gallery.

- Neil Macgregor, a former director of the National Gallery and the British Museum. He called Blunt "a great and generous teacher."

- John White, an art historian.

- Sir Alan Bowness, who ran the Tate Gallery.

- John Golding, who wrote an important book on Cubism.

- Reyner Banham, an influential architectural historian.

- John Shearman, an expert on Mannerism.

- Melvin Day, a former Director of the National Art Gallery of New Zealand.

- Christopher Newall, an expert on the Pre-Raphaelites.

- Michael Jaffé, an expert on Rubens.

- Lee Johnson, an expert on Eugène Delacroix.

- Anita Brookner, an art historian and novelist.

Other Achievements

Blunt also received many honorary awards. He became the picture adviser for the National Trust. He organized exhibitions at the Royal Academy. He edited and wrote many books and articles. He also served on many important committees in the arts.

Works

A special book called Studies in Renaissance and Baroque Art presented to Anthony Blunt on his 60th Birthday was published in 1967. It lists all his writings up to 1966.

Some of his major books include:

- Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450–1600, 1940.

- François Mansart and the Origins of French Classical Architecture, 1941.

- Art and Architecture in France, 1500–1700, 1953.

- Philibert de l'Orme, 1958.

- Nicolas Poussin. A Critical Catalogue, 1966.

- Nicolas Poussin, 1967.

- Sicilian Baroque, 1968.

- Picasso's Guernica, 1969.

- Neapolitan Baroque and Rococo Architecture, 1975.

- Baroque and Rococo Architecture and Decoration, 1978.

- Borromini, 1979.

Important articles he wrote after 1966 include:

- "French Painting, Sculpture and Architecture since 1500", 1972.

- "Rubens and architecture", 1977.

- "Roman Baroque Architecture: the Other Side of the Medal", 1980.

See also

In Spanish: Anthony Blunt para niños

In Spanish: Anthony Blunt para niños

Images for kids