History of art facts for kids

The history of art is all about amazing things humans have made. These objects can be for spiritual reasons, to tell stories, to show ideas, or just to look beautiful. Art includes many different types, like architecture (buildings), sculpture (statues), painting, film, photography, and graphic arts. Today, we also have new art forms like video art, computer art, performance art, animation, television, and video games.

Often, the story of art is told by looking at famous masterpieces from each civilization. This can focus on "high culture," like the Wonders of the World. But art history also includes everyday art, called folk arts or craft. When art historians study these, they might call their work "visual culture" or "material culture." They might also connect it to fields like anthropology (the study of human societies) or archaeology (the study of human history through digging up old things). In these cases, art objects are sometimes called archeological artifacts.

Contents

- Prehistoric Art: The Very First Artists

- Ancient Art: Civilizations Rise

- Islamic Art: Patterns and Calligraphy

- Art of the Americas: Ancient Civilizations

- Asian Art: Diverse Traditions

- Art of Sub-Saharan Africa

- Art of Oceania: Islands and Ancient Roots

- European Art: From Medieval to Modern

- Western Art After 1770: Modern Changes

- See also

Prehistoric Art: The Very First Artists

Prehistoric art was made by people who lived before writing was invented. It includes some of the oldest human-made objects. Some of the first art pieces are decorative items from the Middle Stone Age in Africa. Containers that might have held paints from 100,000 years ago were found in South Africa.

Small statues called Venus figurines were made all over the world, especially in Europe. These figures have exaggerated curves. The most famous ones are the Venus of Hohle Fels from Germany and the Venus of Willendorf from Austria. Most have tiny heads, wide hips, and legs that get thinner towards the bottom. Arms, feet, and faces are often missing.

The Venus of Hohle Fels was found at a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Germany. This site has the oldest non-moving human art ever found. These include carved animal and human-like figures, and the oldest musical instruments. These items are between 43,000 and 35,000 years old.

The most famous prehistoric artworks are the huge Paleolithic cave paintings in Europe. They show animals, especially in places like Lascaux in France. Hundreds of decorated caves are known, from about 38,000 to 12,000 BC. You can find examples in Ukraine, Italy, and Great Britain, but most are in France and Spain. Many people think this art was part of religious rituals, perhaps to help with hunting.

-

Painting of rhinoceroses; (around 32,000–14,000 BC); from France

Ancient Art: Civilizations Rise

Art of the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East covered a huge area, from Turkey to Iran. Many civilizations appeared and disappeared here. One very important region was Mesopotamia, where the first cities and writing began around 4000 BC. Mesopotamia is now parts of Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. It's in the "Fertile Crescent," where early farming and villages first started. Because it was between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, many civilizations lived here, like Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, and Babylonia.

Mesopotamian buildings often used bricks. Famous examples are the ziggurats, which were large temples shaped like step pyramids. The Sumerians laid the groundwork for Western civilization. They created the first city-state (Uruk), organized religion, the first known writing (cuneiforms), irrigation systems, and wheeled vehicles. Cylinder seals, small engraved objects, also appeared here. The Akkadian Empire was the world's first great empire.

Later, the Assyrian Empire took over the Middle East. Their cities had impressive buildings and art. Assyrian art is known for detailed stone carvings (reliefs) showing court life, religious practices, hunting, and battles. These reliefs were once brightly painted and tell us about Assyrian life.

The Babylonians conquered Assyria. In the 6th century BC, Babylon was the world's largest city. Visitors saw the amazing Ishtar Gate, with blue glazed bricks and reliefs of dragons, bulls, and lions. It was named after Ishtar, the goddess of war and love.

Around 550 BC, the Achaemenid Empire (Persia) conquered Babylon. This empire stretched from Egypt to the Indus Valley. Their art mixed styles from across the empire, showing its wealth. Persepolis in Iran was the capital, full of sculptures of religious images and people from the empire.

Other ancient civilizations in the Near East also made art. The Hittite Empire was in Anatolia (modern Turkey). In South Arabia, kingdoms like Saba’ became rich from trading spices. Their human figures were often stylized, using rectangular shapes but with fine details.

-

King of Akkad; around 2250 BC; from the Iraq Museum

-

Stag rhyton (Hittite); around 1400-1200 BC; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Winged bulls (Neo-Assyrian); around 710 BC; from the Louvre

-

Delegation bearing gifts (Persian Achaemenid); around 490 BC; from Persepolis, Iran

Art of Ancient Egypt

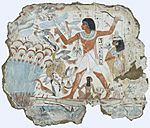

One of the first great civilizations was in Egypt. They created detailed and complex art made by skilled artists. Egyptian art was very religious and full of symbols. Because the pharaoh had so much power, much art was made to honor him, including huge monuments. Egyptian art focused on the idea of immortality. Later Egyptian art includes Coptic and Byzantine styles.

Egyptian buildings were huge, made with large stone blocks and strong columns. Funeral monuments included mastabas (rectangular tombs), pyramids (like those at Giza), and hypogeums (underground tombs like in the Valley of the Kings). Other big buildings were temples, which were often large complexes with avenues of sphinxes and obelisks. Temples like those at Karnak, Luxor, Philae, and Edfu are great examples. Some temples were carved into rocks, like at Abu Simbel.

Egyptian paintings often showed overlapping layers. Important figures, like the Pharaoh, were painted larger than common people. Egyptians drew heads and limbs from the side, but bodies, hands, and eyes from the front. They also developed applied arts, especially woodwork and metalwork. Beautiful examples include cedar furniture decorated with ebony and ivory found in tombs at the Egyptian Museum. The treasures from Tutankhamun's tomb are also very artistic.

Indus Valley Civilization Art

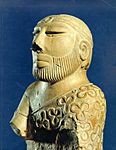

The Indus Valley Civilization, also called the Harappan Civilization (around 2400–1900 BC), was discovered in 1922. It was as advanced as Mesopotamia and Egypt. Its sites stretch from Afghanistan to India. Major cities were Harappa and Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan, and Lothal in India.

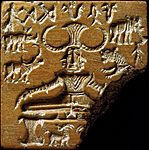

The most common artworks are square and rectangular stamp seals. They show animals, usually bulls, and short texts. Many stylized terracotta figures have also been found. There are also some stone and bronze sculptures that look more realistic than the ceramic ones.

-

Seals with Indus script and impressions; 2500-2000 BC; from the British Museum

Art of Ancient China

The first metal objects in China were made almost 4000 years ago, during the Xia dynasty (around 2100–1700 BC). During the Chinese Bronze Age (the Shang and Zhou dynasties), people used bronze ritual vessels for religious ceremonies. These vessels had many shapes for wine, water, grains, or meat. Some had writing, showing how writing developed. These high-quality vessels were found in the Yellow River Valley. The Shang used them to show their power. When the Zhou conquered the Shang, they continued to use these vessels.

A common design was the taotie, a stylized face with eyes, eyebrows, and horns. We don't know if taotie represented real or mythical creatures.

The mysterious bronzes of Sanxingdui in Sichuan province are unique. Excavations found four pits with bronze, jade, and gold objects. A large bronze statue of a human figure was found, along with over 50 bronze heads. Some heads wore headgear or gold leaf. Bronze tree fragments, leaves, fruits, and birds were also found. Over 4000 objects were discovered in 1986.

The Zhou (1050–221 BC) ruled China longer than any other dynasty. Its last centuries were violent, known as the Warring States period. During this time, new philosophies like Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism appeared.

Qinshi Huangdi united China in 221 BC. He ordered a huge tomb guarded by the Terracotta Army. He also built an early version of the Great Wall. After his death, the Qin (221–206 BC) lasted only three years. The Han Dynasty (202 BC-220 AD) followed, and the Silk Road grew, bringing new cultural ideas to China.

-

Ornamental handle with a bi disc; around 100 BC; from the Museum of the Mausoleum of the Nanyue King

Art of Ancient Greece

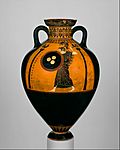

Ancient Greek and Roman art became the basis for all Western art. It focused on beauty and perfect human forms. The Greek poet Horace said that "captive Greece overcame its savage conqueror and brought the arts to rustic Rome." Greek art showed human figures and gods as main subjects. It decorated temples and public buildings, celebrated victories, and honored the dead.

Greek art is usually divided into four periods: Geometric, Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic. During the Classical period (5th and 4th centuries BC), art balanced realism and idealism. Earlier art from the Geometric (9th to 8th centuries BC) and Archaic (7th to 6th centuries BC) periods might look simpler, but their goals were different. Greek artists built on Egyptian art, improving sculpture, painting, architecture, and ceramics. They perfected carving, casting, fresco painting, and building grand structures.

Roman art collectors loved Greek originals and Roman copies. This helped preserve Greek art that might otherwise be lost. Greek images appeared on Roman jewelry, vessels, and even weapons. When rediscovered during the Renaissance, Greek art, passed down through the Roman Empire, became the foundation of Western art until the 19th century.

Since the Classical Age in Athens (5th century BC), the Greek way of building has shaped Western architecture. From around 850 BC to 300 AD, ancient Greek culture thrived. Five of the Wonders of the World were Greek: the Temple of Artemis, the Statue of Zeus, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Colossus of Rhodes, and the Lighthouse of Alexandria. But Ancient Greek architecture is most famous for its temples, like the Parthenon. These inspired later Neoclassical architects. Other important buildings were theatres. Both temples and theatres used clever optical illusions and balanced designs.

Many ancient buildings, like the Parthenon (around 447–432 BC) in Athens, had colorful details. Medieval cathedrals also had colored highlights. This practice of coloring buildings was stopped during the early Renaissance. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo preferred the white look of ancient ruins, which had lost their colors over time due to weather and neglect.

-

Panathenaic amphora (Archaic); around 530 BC; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Temple of Segesta (Italy), 5th century BC

-

Erechtheion (Athens), with its Ionic columns and caryatid porch, 421-405 BC

-

Centuripe vase (Hellenistic); around 300-100 BC; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Art of Ancient Rome

The Roman Empire had a huge and lasting impact on Western art. Roman art is sometimes seen as coming from Greek art, but it also has its own unique features, some from Etruscan art. Roman sculptures were often very realistic, less idealized than Greek ones. Roman architecture often used concrete and invented features like the round arch and dome.

Luxury items like metal-work, gem engraving, ivory carvings, and glass were also important. An invention from Roman glass-blowing was cameo glass. They also made mosaics using small stone cubes (tesserae) or colored terracotta and glass. Wealthy Romans decorated their homes with frescos (wall paintings). Much Roman wall painting survived in Pompeii and Herculaneum, towns buried by Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Romans were greatly influenced by Greek culture. In architecture, they used Greek styles but adapted them. They used the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders more freely than the Greeks. They also added two new orders: the Tuscan (a simpler Doric) and the Composite (a mix of Ionic and Corinthian).

Other important Roman inventions were the arch and the dome. They built aqueducts and huge triumphal arches using arches. Roman emperors celebrated their victories with triumphal arches, like the Arch of Constantine in Rome. The architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio wrote De Architectura, a book that influenced architects for centuries.

After the Middle Ages, the Renaissance began in Florence (Italy). People became very interested in ancient Rome. During this time, art became very lifelike again. The Renaissance also sparked interest in ancient Greek and Roman literature.

-

The Maison Carrée (Nîmes, France), a well-preserved Roman temple, around 2 AD

-

Marine mosaic; 200–230 AD; from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-

Arch of Constantine (Rome), celebrating Constantine the Great's victory, 316 AD

Islamic Art: Patterns and Calligraphy

Islamic art is famous for its detailed geometric patterns, colorful tiles, stylized natural designs, and beautiful calligraphy. Writing has had a huge impact on Islamic art and architecture. Islam began in western Arabia in the 7th century AD with the prophet Muhammad. Within a hundred years, Islamic empires controlled the Middle East, Spain, and parts of Asia and Africa. Because of this, Islamic art and architecture had many regional styles.

As the Islamic world grew, it was influenced by Greek ideas in philosophy and science. This is different from the modern idea that Islamic art is strict and unchanging. Human and animal figures were not rare in Islamic art. Only certain times restricted them, similar to the Byzantine Iconoclasm.

-

Mihrab; 961–976; from the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba, Spain

-

Court of the Lions (Alhambra, Spain), 1362-1391

Art of the Americas: Ancient Civilizations

Mesoamerican Art

Some of the first great civilizations in the Americas developed in Mesoamerica (meaning 'middle Americas'). The most famous are the Mayans and the Aztecs.

The Olmecs (around 1400–400 BC) were the first major civilization in modern-day Mexico. Many Mesoamerican ideas, like building pyramids, complex calendars, gods, and hieroglyphic writing, came from the Olmecs. They made jade and ceramic figures, huge colossal heads, and pyramids with temples on top, all without metal tools. For them, jadeite was more precious than gold and symbolized divine power. 17 Olmec colossal heads have been found, each weighing several tons. Each head wears a helmet, possibly representing kings.

The Maya civilization began around 1800 BC and lasted until the Spanish arrived in the 1500s. They lived in southeast Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador. The Mayans traded with other cities and groups. They created impressive king portraits, colorful ceramic vessels, earthenware figures, wooden sculptures, stelas (carved stone slabs), and complex cities with pyramids. Many well-preserved colorful ceramic vessels were found in noble tombs.

The Aztecs started as a nomadic group and built the largest empire in Mesoamerican history (1427 to 1521). They called themselves Mexica. Historians gave them the name 'Aztecs'. They turned their capital, Tenochtitlan, into a place where artists created amazing artworks for them. Today's Mexico City is built over Tenochtitlan.

-

Colossal head; around 1050 BC; from the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa

-

Seated shaman pendant (Olmec); 9th-5th century BC; from the Dallas Museum of Art

-

Bat effigy (Zapotec); around 50 BC; from the National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico)

-

Portrait of K'inich Janaab Pakal I (Maya; 615–683; from the National Museum of Anthropology

-

Warrior columns (Toltec); around 1000; from Tula de Allende (Mexico)

-

Double-headed serpent (Aztec); around 1450–1521; from the British Museum

Art of Ancient Colombia

Like Mesoamerica, present-day Colombia was home to many cultures before the Spanish arrived. These cultures created beautiful gold body accessories. Many were made of pure gold, but others used tumbaga, an alloy of gold and copper.

-

Pendant (Tairona); 10th–16th century; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Art of the Andean Regions

The ancient civilizations of Peru and Bolivia had unique art styles, including impressive fabric art. Two early important cultures were the Chavín and the Paracas culture.

The Paracas culture, on Peru's south coast, is known for its complex patterned textiles, especially mantles. The Moche controlled river valleys on the north coast, while the Nazca lived in southern Peru's deserts and mountains. The Nazca are famous for the Nazca Lines, huge designs on the desert floor. They also made colorful ceramics and textiles, using at least 10 colors for their pottery. Both cultures thrived around 100–800 AD. Moche pottery is very diverse. In the north, the Wari Empire was known for its stone architecture and sculptures.

The Chimú culture came after the Sicán (700–900 AD). The Chimú made excellent metal art, especially in gold and silver. Later, the Inca Empire (1100–1533) stretched across the Andes Mountains. They crafted precious metal figures and complex textiles. Llamas were important for their wool and for carrying goods.

-

The Hummingbird, one of the Nazca Lines (Nazca); around 200 BC-600 AD; from Peru

-

Portrait head bottle (Moche); 3rd–6th century; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Mosaic figurine of a noble man (Wari); 7th-9th century; from the Kimbell Art Museum

-

Royal tunic (Inca); 1476–1534; from Dumbarton Oaks

Asian Art: Diverse Traditions

Eastern civilization, mainly Asia, has a rich history of art. It's often divided into Indian art, Chinese art, and Japanese art. Because Asia is so big, there are clear differences between East Asian and South Asian art. Pottery was very common, often decorated with patterns or abstract animals, people, or plants. Sculpture and painting were also very widespread.

Art of Central Asia

Central Asian art developed in areas like modern Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Afghanistan. It shows the rich history of many different peoples, religions, and ways of life. The art combines many influences, showing the multicultural nature of Central Asian society. The Silk Road transmission of art, Scythian art, Greco-Buddhist art, and Persianate culture are all part of this history. Central Asia was a crossroads for trade and cultural exchange, linking China to the Mediterranean. Even in the Bronze Age (3rd and 2nd millennium BC), settlements here were part of a large trade network connecting to the Indus Valley, Mesopotamia, and Egypt.

-

Seated figurine (Bactrian); 3rd-2nd millennia BC; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Gur-i Amir Mausoleum (Samarkand, Uzbekistan), 15th century

Art of India

Early Buddhists in India created symbols related to Buddha. Buddhist art really started after the Mauryans, with Kushan art in North India, Greco-Buddhist art in Gandhara, and then the "classic" period of Gupta art. The Andhra school in South India came even earlier.

Many sculptures survive from important sites like Sanchi, Bharhut, and Amaravati. Some are still in their original places, others are in museums. Stupas (Buddhist shrines) were surrounded by fences with four carved gateways called toranas. These were made of stone but looked like wood. They and the stupa walls were heavily decorated with reliefs, often showing the Buddha's life.

Gradually, life-size figures were sculpted, first in deep relief, then standing freely. Mathura art was key in this development, which also applied to Hindu and Jain art. Rock-cut chaitya (prayer halls) and viharas (monasteries) have survived better than similar wooden buildings. The caves at Ajanta, Karle, and Bhaja have early sculptures, but more later works like figures of Buddha and bodhisattvas (enlightened beings) from after 100 AD.

-

The Great Stupa of Sanchi (India), 3rd century-around 100 BC

-

Lion Capital of Ashoka; around 250 BC; from the Sarnath Museum

-

Shiva as lord of the dance; around 11th century; from the Musée Guimet

-

Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (Khajuraho, India), around 1030

-

Durga killing the buffalo demon; around 1150; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Ganesha; around 14th-15th century; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Art of Later Chinese Dynasties

In Eastern Asia, painting grew from calligraphy. Portraits and landscapes were painted on silk. The most impressive sculptures are the ritual bronzes and the bronze sculptures from Sanxingdui. A very famous example of Chinese art is the Terracotta Army. It shows the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China. It was buried with him in 210–209 BC to protect him in the afterlife.

Chinese art is one of the oldest continuous art traditions. It has a strong sense of its own history. What Westerners call "decorative arts" are very important in Chinese art, like Chinese ceramics. Much of the best work was made in large workshops by unknown artists. Chinese palaces and homes were filled with dazzling objects made from gold, silver, mother of pearl, ivory, wood, lacquer, jade, silk, and paper.

-

Buddha Pagoda (China), 1056

-

Autumn Colours on the Qiao and Hua Mountains; by Zhao Mengfu; 1296; from the National Palace Museum

-

Lacquer dish with garden scene; late 14th century; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, Temple of Heaven (Beijing), 1545, rebuilt in 1890

-

Cloisonné box; 18th century; from the Walters Art Museum

Art of Japan

Japanese art includes many styles and materials. These range from ancient pottery to sculpture, ink painting, calligraphy, ukiyo-e prints, ceramics, origami, and modern manga (comics).

The first settlers in Japan, the Jōmon people (around 11,000–300 BC), made richly decorated pottery and clay figures called dogū. Japan often had sudden new ideas from outside, followed by long periods of little contact. Over time, the Japanese learned to take foreign ideas and make them their own. The earliest complex art in Japan (7th and 8th centuries) was linked to Buddhism. In the 9th century, as Japan looked less to China, everyday art became more important. Both religious and non-religious art thrived until the late 15th century.

After the Ōnin War (1467–1477), Japan went through a time of trouble. Under the Tokugawa shogunate, religion became less central, and art was mostly non-religious.

-

Temple of the Golden Pavilion (Kyoto), a Zen Buddhist temple, 1398

-

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, by Katsushika Hokusai; around 1830–1832; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Plum Park in Kameido; by Hiroshige; 1857; from the Rijksmuseum

Art of Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan African art includes sculpture and folk art. Famous sculptures include brass castings from the Benin people, Igbo Ukwu, and the Kingdom of Ifẹ. Terracotta works come from Djenne-Jeno, Ife, and the older Nok culture.

Around the 11th century AD, during Europe's Middle Ages, a kingdom in Great Zimbabwe built grand architecture and made gold sculptures and jewelry. The Yoruba people in Nigeria also cast impressive brass sculptures. In the Benin Kingdom (Nigeria), elegant altar tusks, brass heads, and brass plaques were created. The British ended the Benin Kingdom in 1897, and much of its art is no longer in Nigeria.

Sub-Saharan Africa has many different cultures. Some notable groups include the Dogon people from Mali; the Edo, Yoruba, Igbo, and Nok civilization from Nigeria; the Kuba and Luba people from Central Africa; the Ashanti people from Ghana; the Zulu people from Southern Africa; and the Fang people from Equatorial Guinea.

African art forms are very lively and important to the lives of African people. Artworks are made for specific purposes and can change over time as materials are added to make them more beautiful or powerful. Many traditional African art forms connect to the spirit world. The more an artwork is used and blessed, the more abstract it becomes as layers are added and original details wear away.

-

Seated figure; by artists of the Nok culture; 5th century BC-5th century AD; from the Musée du Quai Branly

-

Head of a king or dignitary; by artists of the Yoruba people; 12th-15th century; from the Ethnological Museum of Berlin

Art of Oceania: Islands and Ancient Roots

The Art of Oceania includes areas like Micronesia, Polynesia, Australia, New Zealand, and Melanesia. It often focuses on themes like ancestry, warfare, the body, gender, trade, religion, and tourism. Sadly, not much ancient art from Oceania has survived. Scholars think this is because artists used materials like wood and feathers, which don't last long in tropical climates.

Our understanding of Oceania's art began when Westerners, like Captain James Cook, started documenting it in the 18th century. In the early 20th century, French artist Paul Gauguin lived in Tahiti and made modern art inspired by the local culture. The art of indigenous Australia often looks like modern abstract art, but it has very deep roots in local traditions.

The art of Oceania is one of the last great art traditions to be widely recognized. Even though it's one of the longest continuous art traditions in the world (dating back at least fifty thousand years), it was not well known until the second half of the 20th century.

The materials used in Aboriginal art of Australia often break down easily. This makes it hard to know how old many of the art forms practiced today are. The most lasting forms are the many rock engravings and paintings found across the continent. In Arnhem Land, there's evidence that paintings were made fifty thousand years ago, even older than the famous cave paintings in Europe like Altamira and Lascaux.

-

Hoa Hakananai'a, an example of a moai; around 1200 AD; from the British Museum

-

Taurapa (Māori canoe sternpost); late 18th-early 19th century; from the Musée du Quai Branly

European Art: From Medieval to Modern

Medieval Art: Faith and Form

The Medieval era began around 300 AD, after the Roman Empire declined. It lasted for about a thousand years, until the Renaissance started around 1400. This period includes Early Christian art, Byzantine art, Anglo-Saxon art, Viking art, Ottonian art, Romanesque art, and Gothic art. Islamic art was also very important in the eastern Mediterranean. Medieval art combined Roman and Byzantine traditions with the art of northern Europe.

In Byzantine and Gothic art of the Middle Ages, the church was very powerful, so much art was religious. Gold was often used in paintings, and figures were shown in simple forms.

Byzantine Art: Domes and Mosaics

Byzantine art refers to Christian Greek art from the Eastern Roman Empire. This empire lasted until 1453. Many Eastern Orthodox countries and some Muslim states kept parts of Byzantine culture and art for centuries.

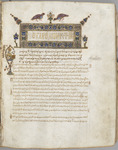

Most surviving Byzantine art is religious and follows strict traditions. It translates church ideas into art. Painting in fresco (on wet plaster), illuminated manuscripts (decorated books), wood panels, and especially mosaics were common. Sculptures were rare, except for small carved ivories. Manuscript paintings kept some classical realism that was missing in larger works.

Byzantine art was highly valued in Western Europe and influenced medieval art until the end of the period. This was especially true in Italy, where Byzantine styles influenced Italian Renaissance art. Byzantine art spread throughout the Orthodox world. Its architecture, especially religious buildings, influenced regions from Egypt to Russia.

Byzantine architecture is known for its domes. It also used marble columns, coffered ceilings, and rich decorations, including many mosaics with gold backgrounds. Byzantine architects used stone and brick instead of marble. Mosaics covered brick walls and other surfaces where frescoes wouldn't last. Good examples of early Byzantine mosaics are in Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki, and the Basilicas of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo and San Vitale in Ravenna, and Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Ancient Greek temples and Byzantine churches were very different. In ancient times, the outside of a temple was most important because only priests went inside. Ceremonies were held outside, and people saw the temple's facade with columns. Christian church services were held inside, so the outside usually had little decoration.

Ottonian Art: German Grandeur

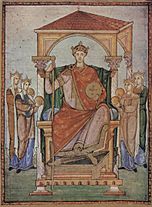

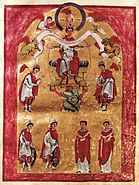

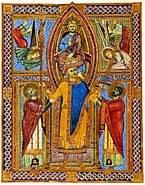

Ottonian art is a style of pre-Romanesque German art. It also includes some works from the Netherlands, northern Italy, and eastern France. It's named after the Ottonian dynasty that ruled Germany and northern Italy from 919 to 1024. Along with Ottonian architecture, it's a key part of the Ottonian Renaissance (around 951–1024).

The style didn't start or end exactly with the dynasty's rule. It began a few decades into their rule and continued into the next dynasty. Ottonian art follows Carolingian art and comes before Romanesque art. Like Carolingian art, it was mostly found in small cities and important monasteries, as well as in the emperor's court.

After the Carolingian Empire declined, the Holy Roman Empire was re-established under the Ottonian dynasty. This led to a renewed interest in the Empire and a reformed Church, creating a time of great cultural and artistic energy. Masterpieces were made that combined ideas from Late Antique, Carolingian, and Byzantine art.

Most surviving Ottonian art is religious, like illuminated manuscripts (decorated books) and metalwork. It was made for the emperor's court and important church figures. However, much of it was meant for the public, especially pilgrims.

The style is generally grand and heavy. At first, it was less refined than Carolingian art, with less direct influence from Byzantine art. But around 1000, many works became very intense and expressive. They combined a serious, monumental feel with a vibrant inner life and a visionary quality.

Romanesque Art: Stone and Frescoes

The Romanesque style was the first art style to spread across all of Europe after the Roman Empire. It lasted from the mid-10th century to the 13th century. During this time, large stone buildings with complex designs became popular again.

Romanesque churches are known for their strong, clear shapes and geometric design. The buildings are simple but decorated with carvings on capitals (tops of columns) and doorways. Their insides were often covered with frescoes (wall paintings). Geometric and plant patterns gradually turned into more three-dimensional human figures.

St. Michael's Church, Hildesheim, Germany (1001–1030), is considered an early Romanesque church.

From the mid-11th to early 13th centuries, Romanesque paintings were flat and used bold lines and geometric shapes, especially for clothing. Symmetry and front-facing figures were common. Almost all Western churches were painted. Most of this work was done by traveling artists, not monks. Basic outlines were drawn on wet plaster with earth colors. A limited palette of white, red, yellow, and blue was used for strong visual effect.

The later 11th and 12th centuries were a great time for monasteries in Europe. There were big changes in the economy, society, and politics, leading to more wealth for landowners, including monasteries. More books were needed, and this wealth allowed many manuscripts to be richly illuminated (decorated).

One famous artwork from this time is the 70-meter-long Bayeux Tapestry. It shows the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England, including the Battle of Hastings. It's believed to be from the 11th century and tells the story from the Norman point of view. It was likely made in England by women. It is now kept in France.

-

Speyer cathedral (Germany), 1030-1106

-

Manuscript Illumination with Initial V, from a Bible; around 1175–1195; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

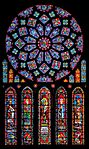

Gothic Art: Soaring Cathedrals

Gothic art developed in Northern France from Romanesque art in the 12th century AD. It grew alongside Gothic architecture. It spread across Western Europe and much of Southern and Central Europe. In the late 14th century, the fancy court style of International Gothic appeared and continued until the late 15th century.

The impressive Gothic cathedrals, with their sculptures and stained glass windows, are perfect examples of the Gothic style. It's different from Romanesque because it uses rib-shaped vaults and pointed arches (ogives). Instead of thick Romanesque walls, Gothic buildings are thin and tall. Spiral stairs in towers are also common in Gothic architecture.

Gothic painting, often done in tempera and later oils on wood panels, as well as fresco, looks more "natural" than Romanesque art. It showed the human side of religious stories and gave characters individual emotions. As cities grew and more people could afford art, the art market changed. This can be seen in Gothic manuscript illumination. Workshops hired specialists for different parts of a page, like figures or decorative borders.

-

The Sainte-Chapelle (Paris), 1243–1248

-

Arrest of Christ and Annunciation of the Virgin; by Jean Pucelle; 1324–1328; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Renaissance Art: A Rebirth of Ideas

The Renaissance, which includes Early, Northern, and High Renaissance, means "rebirth." It describes a new interest in ancient Greek and Roman art in Europe. For the first time since ancient times, art became very lifelike. Renaissance artists also studied nature, learning about the human body, animals, plants, space, perspective, and light. Religious subjects were common, but mythological stories were also painted. There wasn't one single Renaissance style; each artist developed their own unique look.

The Early Renaissance began in Florence, Italy, in the early 15th century. It was a time of great creativity. Artists broke away from Byzantine art styles. There was a surge of interest in classical literature, philosophy, and art. Trade grew, new continents were discovered, and new inventions appeared. People rediscovered ancient Roman art and literature, and Greek and Latin texts led to new ideas about individualism and reason, called humanism. Humanists focused on life in the present and the importance of individual thought, which changed how artists worked.

While the Renaissance is strongly linked to Italy, especially Florence, Rome, and Venice, the rest of Western Europe also took part. The Northern Renaissance happened north of the Alps from the early 15th century. There was a big difference between Northern and Italian Renaissance art. Northern artists didn't try to bring back ancient Greek and Roman ideas like the Italians. In the south, Italian artists were amazed by the study of nature and society, and by the deep colors Northern artists achieved with new oil paint. The Protestant Reformation increased Northern interest in everyday paintings, like portraits and landscapes. Two key Northern artists are Hieronymus Bosch, known for his surreal paintings like The Garden of Earthly Delights, and Albrecht Dürer, who made printmaking an art form.

The High Renaissance took place in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. As the Pope's power grew in Rome, several popes ordered art and architecture to bring back the city's former glory. Raphael and Michelangelo created huge projects for the popes. The most famous artwork from this time is probably the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Mannerism came after the High Renaissance. It moved away from harmony and realistic art, using exaggerated forms, long proportions, and brighter colors. It started in Italy between 1510 and 1520. Artists wanted to be original. The name comes from the Italian maniera, meaning 'style'. It was meant to describe the high standard of the High Renaissance, but it led to art that was more about showing off style.

-

The Florence Cathedral (Italy), 1294–1436

-

Crucifix; by Giotto; around 1300; from Santa Maria Novella

-

Arnolfini Portrait; by Jan van Eyck; 1434; from the National Gallery (London)

-

Saint George and the Dragon; by Paolo Uccello; around 1470; from the National Gallery (London)

-

Primavera; by Sandro Botticelli; around 1478; from the Uffizi Gallery

-

The Tempietto (Rome), 1502, by Donato Bramante

-

Mona Lisa; by Leonardo da Vinci; around 1503-1519; from the Louvre

-

Sistine Chapel ceiling; by Michelangelo; 1508–1512; from the Sistine Chapel

-

The School of Athens; by Raphael; 1509–1510; from the Apostolic Palace

-

The Rhinoceros; by Albrecht Dürer; 1515; from the National Gallery of Art

-

The Tower of Babel; by Pieter Bruegel the Elder; 1563; from the Kunsthistorisches Museum

Baroque Art: Drama and Emotion

The 17th century was a time of big changes, with new inventions like the telescope and microscope. In religion, the Catholic Church reacted to the rise of Protestantism with the Counter-Reformation. They decided that art should inspire strong religious feelings.

Baroque art appeared in the late 16th century, after Mannerism. The name might come from the Portuguese word 'barocco', meaning a misshaped pearl. Baroque art combined emotion, movement, and drama with strong colors and realism. At the Council of Trent (1545-1563), it was decided that religious art should encourage faith, be realistic, and glorify the Catholic Church. In the next century, Baroque art built on Renaissance ideas but also created new kinds of art, especially landscapes.

Baroque and its later style, Rococo, were the first truly global art styles. They were popular for over two centuries (around 1580 to 1750) in Europe, Latin America, and beyond. It started in Bologna and Rome in the 1580s and quickly spread through Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, and other countries. The Portuguese, Spanish, and French empires, along with Dutch trade, helped spread these styles to the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

Like paintings and sculptures, Baroque cathedrals and palaces used illusion and drama. They often had dramatic lighting and richly decorated interiors that blended architecture, painting, and sculpture. Another key feature was movement, created with curves, Solomonic columns (twisted columns), and oval shapes.

In France, Baroque is linked to the reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715). Many grand buildings were built during his rule, like the Palace of Versailles and the Louvre Colonnade. Baroque buildings aimed to grab attention and dominate their surroundings. Applied arts also thrived. Baroque furniture was often as grand as the rooms it decorated. Famous furniture maker André Charles Boulle was known for his marquetry technique, using tortoiseshell and brass. His works also had gilded bronze decorations. Large Gobelins tapestries showed scenes from ancient times, and Savonnerie manufactory made detailed carpets for the Louvre. Chinese porcelain, Delftware, and mirrors from Saint-Gobain spread quickly to palaces across Europe. During Louis XIV's reign, large mirrors above fireplaces became popular and stayed that way for a long time.

-

The Rape of the Sabine Women; by Nicolas Poussin; 1634–1635; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Night Watch; by Rembrandt; 1642; from the Rijksmuseum

-

Ecstasy of Saint Teresa; by Gian Lorenzo Bernini; 1647–1652; from Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

-

Las Meninas; by Diego Velázquez; 1656; from the Museo del Prado

-

Vanitas Still Life; by Maria van Oosterwijck; 1668; from the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

-

Dôme des Invalides (Paris), 1677–1706

-

Commode; by André Charles Boulle; around 1710–1732; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rococo Art: Playful and Elegant

Rococo started around 1720 in Paris. It's known for natural shapes, soft colors, curvy lines, and themes of love, nature, and light-hearted fun. It aimed for delicacy, joy, youthfulness, and charm.

Rococo began in France as a reaction against the heavy Baroque style of Louis XIV's court at the Palace of Versailles. It became linked to the powerful Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764), the mistress of the new king Louis XV. So, it was also called 'Pompadour'. The name 'Rococo' comes from the French word 'rocaille', meaning pebble, referring to stones and shells used to decorate caves. Similar shell shapes became common in Rococo design. It started as a design and decorative arts style, known for elegant flowing shapes. Architecture, then painting and sculpture, followed this trend. The French painter most linked to Rococo is Jean-Antoine Watteau, whose pastoral scenes dominated the early 18th century.

While there are some important Rococo churches in Bavaria, like the Wieskirche, the style is mostly linked to non-religious buildings. These were grand palaces and salons where educated people met to discuss ideas. In Paris, Rococo became popular as salons became new social gatherings, often decorated in this style. The Salon Oval de la Princesse of the Hôtel de Soubise is a beautiful example. Rococo changed furniture, favoring smaller pieces with thin frames and delicate, often uneven, decoration. It sometimes included elements of chinoiserie, showing a love for Chinese objects.

The style quickly spread across Europe and even to the Ottoman Turkey and China. This happened thanks to design books with cartouches, arabesques, and shell work.

-

The Embarkation for Cythera; by Jean-Antoine Watteau; 1718; from Schloss Charlottenburg

-

Madame de Pompadour; by François Boucher; 1756; from the Alte Pinakothek

-

The Swing; by Jean-Honoré Fragonard; 1767; from the Wallace Collection

-

Marie-Antoinette with the Rose; by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun; 1783; from the Palace of Versailles

Neoclassicism: Order and Reason

After ancient Roman cities like Pompeii and Herculaneum were excavated starting in 1748, there was a new interest in ancient art. Neoclassicism became popular in Western art from the mid-18th century until the 1830s. It emphasized order and control, reacting against the playful Rococo style. It fit with the rational thinking of the 'Age of Enlightenment'.

Enlightenment thinkers wanted a rational, moral art style to replace Rococo. This matched the idea that Classical art was about realism, restraint, and order. Inspired by ancient Greek and Roman art, Neoclassicism began in Rome and spread across Europe, especially in England and France. Rome was a main stop on the Grand Tour for rich travelers who wanted to see classical sights and collect ancient items. Neoclassical paintings often showed figures posed like classical statues, in settings with archaeological details. The style preferred Greek art over Roman, seeing it as purer.

In 1789, France was on the edge of its first revolution. Neoclassicism expressed patriotic feelings. Politics and art were closely linked. Artists believed art should be serious, valuing drawings over painting. Smooth lines and paint without visible brushstrokes were ideal. Both painting and sculpture showed calmness and restraint, focusing on heroic themes like self-sacrifice and nationalism.

This movement led to Romanticism, which appeared after the revolution's idealism faded. Neoclassicism isn't the opposite of Romanticism, but in some ways, it was an early form of it.

-

Fantasy View with the Pantheon and other Monuments of Ancient Rome, by Giovanni Paolo Panini, 1737, from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

-

The ancient Capitol ascended by approximately one hundred steps . . ., by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, around 1750, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Petit Trianon, Versailles, France, 1764

-

A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery, by Joseph Wright of Derby, around 1766, from the Derby Museum and Art Gallery

-

The Hall, Osterley Park, London, 1767

-

The Artist and her Daughter, by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, around 1785, from the Louvre

Western Art After 1770: Modern Changes

Many art historians say modern art began in the late 18th or mid-19th century. Art historian H. Harvard Arnason noted a "gradual change over a hundred years." Events like the Age of Enlightenment, revolutions in America and France, and the Industrial Revolution greatly affected Western culture. People, goods, ideas, and information could travel faster than ever. These changes were seen in art.

The invention of photography in the 1830s also changed art, especially painting. By the early 19th century, artists were no longer just craftsmen for the church or kings. The idea of "art for art's sake" grew, where the artist's ideas were highly valued. A wealthy middle and upper class, especially in Paris and London, became art patrons. A split began in the late 18th century between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. These styles, and many others, spread like waves, mixing and changing over time.

Modern art increasingly took ideas from other cultures. This included the exotic look of Orientalism, the deeper influence of Japonisme, and the arts of Oceania, Africa, and the Americas. For example, Pablo Picasso was influenced by Iberian sculpture, African sculpture, and Primitivism. Japanese woodcuts also had a huge impact on Impressionism. Later in the 20th century, Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism became very important.

-

Newton's Cenotaph, exterior by night; by Étienne-Louis Boullée; 1784; from the Bibliothèque Nationale

-

The Dog; Francisco de Goya; around 1819–1823; from the Museo del Prado

-

Toothless Man Laughing; Honoré Daumier; 1832–33; from the Musée d'Orsay

19th Century Art Movements

Romanticism: Emotion and Nature

Romanticism began in the late 18th century and was very popular in the first half of the 19th century. It appeared in music, literature, architecture, and visual arts. It grew from a disappointment with the logical thinking of the 18th-century Enlightenment. While often seen as the opposite of Neoclassicism, many Romantic artists still liked classical ideas.

Romanticism focused on strong emotions, imagination, and the powerful force of nature. Nature was seen as bigger and stronger than humans, with the potential for disaster. "Neoclassicism is a new revival of classical antiquity... while Romanticism refers not to a specific style but to an attitude of mind that may reveal itself in any number of ways."

One early example of Romanticism was the English landscape garden. These gardens were designed to look natural, unlike the formal gardens of the time. This idea spread across Europe and America. In architecture, Romantics often looked beyond Greek and Roman styles. They revived Gothic forms and other exotic styles. The Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) in London is an example of Romantic architecture, also called Gothic Revival.

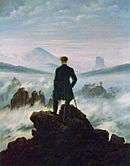

In painting, Romanticism is seen in the works of Francisco Goya (Spain), Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault (France), William Blake and William Turner (England), and Caspar David Friedrich (Germany). As Romanticism continued, some parts of it developed into symbolism.

-

Elohim Creating Adam; by William Blake; 1795; from Tate Britain

-

The Third of May 1808; by Francisco Goya; 1814; from the Museo del Prado

-

Palace of Westminster (London), 1840–1870

-

Neuschwanstein Castle, Germany, 1869-1886

Academism: Rules and Ideals

Academism was about setting rules for art that could be taught in art academies. It promoted classical ideas of beauty and artistic perfection. There was a strict order of subjects for paintings. Historical events (including biblical and classical ones) were at the top, followed by portraits and landscapes. At the bottom were still life and genre painting (scenes of everyday life). Nicolas Poussin's works and ideas were very important in developing academism.

During the 18th century, many academies were founded across Europe. They later controlled much of 19th-century art. Young artists had to pass an exam to study there for many years. Most 19th-century French art movements were outside or even against academism's values.

Some important French academic artists were William Bouguereau, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and Alexandre Cabanel. Academic art is closely related to Beaux-Arts architecture, which developed in Paris and shared similar classical ideals.

-

The Roses of Heliogabalus; by Lawrence Alma-Tadema; 1888; private collection

Revivalism and Eclecticism: Looking to the Past

In architecture and applied arts, the 19th century is known for "revivals" of past styles. One famous style was Gothic Revival (Neo-Gothic), which first appeared in England in the mid-18th century. However, the early 19th century was dominated by Neoclassicism.

Later, between 1830 and 1840, people became interested in rediscovering past styles, from the Middle Ages to the 18th century. This was influenced by Romanticism. Until World War I, old styles were very popular in architecture and applied arts. Certain styles became linked to certain building types: Egyptian for prisons, Gothic for churches, or Renaissance Revival for banks. These choices were based on ideas like pharaohs with death, the Middle Ages with Christianity, or the Medici family with banking.

Sometimes, these styles were also seen as "national styles," like Gothic Revival in the UK. Architects used these styles to give buildings the feeling of a glorious past. Some architects linked historical styles, especially medieval ones, with an idealized, natural life, comparing it to their own time.

Even with all this revivalism, there was still originality. Architects and craftspeople, especially in the second half of the 19th century, mixed styles. They took elements from different eras and areas and combined them. This practice is called eclecticism. This happened during a time when World's Fairs encouraged countries to invent new industrial ways of creating things.

-

Gothic Revival - Pair of vases; manufactured in 1832, decorated in 1844; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Rococo Revival - Apartment building no. 8 on Rue de Miromesnil (Paris), 1900

Realism: Everyday Life in Art

Realism appeared in the mid-19th century, around 1840. It had similar movements in sculpture, literature, and drama (often called Naturalism in literature). In 19th-century painting, Realism focused on the subjects shown, rather than the style. Realist paintings usually showed ordinary places and people doing everyday things. This was different from grand landscapes, mythological gods, biblical scenes, or historical events that were common before. Gustave Courbet famously said, "I cannot paint an angel because I have never seen one."

Realism was also a reaction against the dramatic and emotional works of Romanticism. The term "realism" here means showing things as they are, compared to the idealized images of Neoclassicism or the romanticized images of Romanticism. Artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Honoré Daumier were linked to realism. Jean-François Millet of the Barbizon School was also important. But Gustave Courbet was perhaps the main figure. He called himself a realist and influenced younger artists like Édouard Manet. A key part of realism was painting landscapes en plein air (outdoors), which later influenced impressionism.

Beyond France, realism is seen in artists like Wilhelm Leibl (Germany), Ford Madox Brown (England), and Winslow Homer (United States). Art historian H. H. Arnason noted that these movements—Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and Realism—are closely connected and blend into each other. This becomes even more true as art moves into the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

-

The Gleaners; by Jean-François Millet; 1857; from the Musée d'Orsay

-

The Third-Class Carriage; by Honoré Daumier; around 1862–1864; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Impressionism: Capturing Light

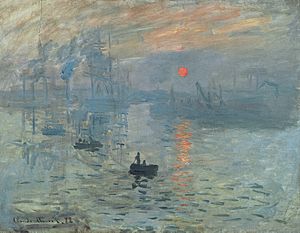

Impressionism began in France, influenced by Realism and painters who worked en plein air (outdoors). Starting in the late 1850s, several Impressionists met as students in Paris. Their new work was often rejected by the traditional art juries. In 1874, they formed their own group and held their first exhibition in Paris. Key artists included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro. While mainly painters, Degas and Renoir also made sculptures. By 1885, Impressionism was well-known, but younger artists were already pushing beyond it. Artists from Russia, Australia, America, and Latin America soon adopted Impressionist styles.

Many Impressionist techniques were new. Paintings were often finished quickly, with wet paint applied to wet paint. Instead of mixing colors, pure colors were often placed side by side in thick strokes. Black was used very little, and lines were replaced by nuanced color strokes. Art historian H. W. Janson said this "strengthens the unity of the actual painted surface."

Impressionist paintings usually showed landscapes, portraits, still lifes, home scenes, and daily life. Compositions often used unusual angles, looking spontaneous. The paintings rarely had deep symbolic meanings. They focused on light, shadow, atmosphere, and reflections, sometimes showing how these elements changed over time. The painting itself became the subject. It was truly "art for art's sake."

-

At the Races in the Countryside; by Edgar Degas; 1869; from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-

Boulevard des Capucines; by Claude Monet; 1873; from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

-

Hoarfrost: Old Road to Ennery, Pontoise; by Camille Pissarro; 1873; from the Musée d'Orsay

-

Banks of the Seine near Bougival; by Alfred Sisley; 1873; from the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

-

La Loge; Pierre-Auguste Renoir; 1874; from the Courtauld Gallery

-

The Floor Scrapers; by Gustave Caillebotte; 1875; from the Musée d'Orsay

-

Paris Street; Rainy Day; by Gustave Caillebotte; 1877; from the Art Institute of Chicago

-

Summer's Day; by Berthe Morisot; 1879; from the National Portrait Gallery, London

-

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère; by Édouard Manet; 1881–1882; from the Courtauld Institute of Art

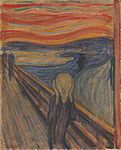

Symbolism: Hidden Meanings

Symbolism began in France and Belgium in the late 19th century and spread across Europe. It grew from Romanticism, with poetry and literature being very important, especially Charles Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du mal (1857). Symbolism also appeared in poetry, literature, drama, and music. In architecture and decorative arts, it was closely linked to Art Nouveau.

Symbolism often mixed with other art movements like Post-Impressionism, Les Nabis, and Art Nouveau. Artists like James McNeill Whistler, Ferdinand Hodler, and James Ensor were connected to Symbolism. Art historian Robert L. Delevoy said, "Symbolism was less a school than the atmosphere of a period." It faded with the rise of Fauvism and Cubism, but influenced Metaphysical art and Surrealism.

The subjects and meanings in Symbolist art are often hidden. They use metaphors or allegories to create personal emotions and ideas in the viewer, without directly stating the subject. The poet Stéphane Mallarmé wrote, "depict not the thing but the effect it produces." The English painter George Frederic Watts said, "I paint ideas, not things."

-

The Scream; by Edvard Munch; 1893; from the National Gallery (Norway)

-

Green Death; by Odilon Redon; around 1905; from the Museum of Modern Art

Post-Impressionism: Beyond Impressions

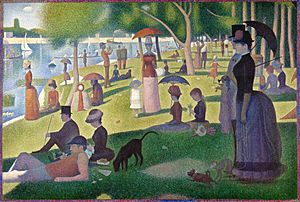

Post-Impressionism is a term for a group of diverse artists. It mainly refers to four influential artists: Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Vincent van Gogh. Each went through an Impressionist phase but developed very original styles. Their work influenced much of the avant-garde art before World War I, including Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism. Cézanne and Van Gogh often worked alone, while Seurat and Gauguin worked in groups. Toulouse-Lautrec was also an important painter and graphic artist.

More broadly, Post-Impressionism includes many French and Belgian artists who worked in different styles. Most were influenced by Impressionism but pushed their art further, sometimes as a logical step, other times as a reaction. Post-Impressionists often painted Impressionist subjects, but their work, especially Synthetism, often included symbolism, spiritualism, and moody atmospheres not usually found in Impressionism. Unusual colors, patterns, flat areas, and extreme perspectives moved modernism closer to abstraction and set a standard for experimentation.

Neo-Impressionism (Divisionism or Pointillism, around 1884–1894) explored light and color using scientific theories. They created mosaics of pure color brushstrokes, sometimes in rhythmic patterns. Leading artists were Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. This style influenced Fauvism and appeared in Expressionism and Cubism.

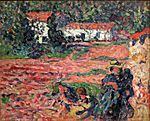

Synthetism (Cloisonnism around 1888–1903) was developed by Émile Bernard and Paul Gauguin. The style looked like cloisonné enamel or stained glass, with flat, bold colors outlined in black. Synthetism, seen in Gauguin's work, is a broader term. It greatly influenced Fauvism and Expressionism.

Les Nabis (around 1890–1905: Hebrew for prophets) was a larger movement in France and Belgium. It drew ideas from Synthetism, Neo-Impressionism, Symbolism, and Art Nouveau. Their theories and enthusiasm for new art were perhaps more influential than their art itself, setting the stage for many movements in the early 20th century. Artists like Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard are good examples of Les Nabis.

-

The Starry Night; by Vincent van Gogh; 1889; from the Museum of Modern Art

-

Félix Fénéon; by Paul Signac; 1890; from the Museum of Modern Art

-

At the Moulin Rouge; by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec; 1892/1895; from the Art Institute of Chicago

Early 20th Century Art Movements

The history of 20th-century art is about endless possibilities and the search for new standards. Art movements like Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, abstract art, Dadaism, and Surrealism led to new creative styles. More global interaction meant other cultures influenced Western art. For example, Pablo Picasso was influenced by Iberian sculpture, African sculpture, and Primitivism. Japonism and Japanese woodcuts also greatly influenced Impressionism. The interest in Oceanic art by Paul Gauguin and African sculptures by Picasso and Henri Matisse also had a big impact. Later in the 20th century, Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism became famous.

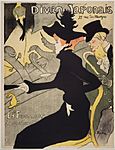

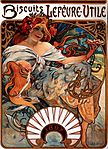

Art Nouveau: New Art, Organic Forms

Art Nouveau (meaning 'new art' in French) was an international art and design movement. It appeared in the late 19th century and lasted until World War I in 1914. It became very famous at the 1900 World's Fair in Paris. It tried to create a unique and modern style that captured the spirit of the new century. It appeared in painting, illustration, sculpture, jewelry, metalwork, glass, ceramics, textiles, graphic design, furniture, architecture, and fashion. Art Nouveau artists wanted to raise the status of crafts and design to the level of fine art.

The movement is known for its curvy, organic shapes, like flowers, vines, leaves, insects, and animals. Artists like Alphonse Mucha, Victor Horta, Hector Guimard, Antoni Gaudí, René Lalique, and Émile Gallé used these forms. Art Nouveau designs and buildings were often asymmetrical. While it had clear characteristics, the style also had many regional differences.

Even though it was a short-lived trend, it paved the way for modern architecture and design in the 20th century. It was the first architectural style without historical examples. The 19th century was known for "Historicism," which meant using styles from past eras. Around 1870-1900, people started criticizing historicism. Despite this, Art Nouveau was also influenced by past styles like Celtic, Gothic, and Rococo art, as well as the Arts and Crafts movement, Aestheticism, Symbolism, and especially Japanese art.

-

Divan Japonais; by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec; around 1893–1894; from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-

Le Printemps; by Eugène Grasset; 1894; from the Musée des Arts Décoratifs

-

Casa Batlló (Barcelona, Spain), an Art Nouveau masterpiece, 1904–1906

-

The Kiss; by Gustav Klimt; 1907–1908; from the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

-

Biscuits Lefèvre-Utile, advertisement; by Alfons Mucha; 1897; private collection

-

Desk (Art Nouveau); by Émile Gallé; 1900; from the Musée d'Orsay

Fauvism: Wild Colors

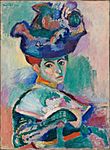

Fauvism grew from Post-Impressionism and became the first major art movement of the 20th century. It started around 1895 when Henri Matisse, the main figure, joined Gustave Moreau's studio. There he met other artists like Georges Rouault and Albert Marquet. Marquet said that by 1898, he and Matisse were already painting in the "Fauve manner." By 1902–03, the group grew to include André Derain, Georges Braque, and others.

During this time, influential exhibitions of artists like Seurat, Van Gogh, and Cézanne were held in Paris. Matisse and Derain collected African carvings, which were new and interesting at the time. The artists exhibited regularly, and in 1905, their work caused a sensation. An art critic, Louis Vauxcelles, saw their work and said, "Well! well! Donatello in the mist of wild beasts!" (Donatello chez les fauves). The name "Fauves" (wild beasts) stuck. Unlike the Impressionists, the Fauves found an eager audience by 1906–1907. However, Fauvism mostly ended in 1908 as Cubism appeared. Only Matisse and Raoul Dufy continued to explore Fauvism into the 1950s.

The Fauves painted landscapes outdoors, interiors, figures, and still lifes. They used loose, thick brushstrokes and bright, often clashing, unnatural colors, sometimes straight from the tube. Gauguin's influence, with his use of flat, pure colors and interest in primitivism, was important. Matisse explained that Fauvism was a shift from drawing as the main basis of painting to color. They showed their subjects almost abstractly.

-

Woman with a Hat; by Henri Matisse; 1905; from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

-

Charing Cross Bridge, London; by André Derain; 1906; from the National Gallery of Art

-

La Ciotat; by Othon Friesz; 1907; unknown collection

Expressionism: Feeling Over Reality

Expressionism was an international movement in painting, sculpture, graphic arts, poetry, literature, theater, film, and architecture. Most historians say it began in 1905 with the founding of Die Brücke (The Bridge). However, some artists were already making Expressionist-like work before then, like Edvard Munch and Emil Nolde. Many of these artists later joined Expressionist groups.

Expressionist painting uses loose, spontaneous, and often thick brushstrokes. It often showed how the artist felt about their subject, rather than what it looked like. It put intuition and gut feelings over realistic representations. Expressionism often had feelings of anxiety or joy, and focused on modern life and social issues. Woodcut prints were very important in Expressionism. It sometimes mixed with other styles like symbolism, fauvism, and cubism.

Die Brücke (The Bridge: 1905 -1913) wanted to connect "all revolutionary elements." It was founded by four architecture students: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Fritz Bleyl. They made paintings, carvings, and prints. They were influenced by Gothic art, primitivism, Art Nouveau, and developments in Paris, especially Van Gogh and Fauvism.

Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider: 1911–1914), founded by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, was a less formal group. They organized art exhibitions from Paris and Europe, as well as their own. Kandinsky's book Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912) shared his ideas on non-objective art. The Blue Rider ended with World War I.

After World War I, many artists moved away from avant-garde styles. This trend was called New Objectivity (around 1919–1933) in Germany. It showed disillusionment and strong social criticism. The Staatliches Bauhaus (School of Building: 1919–1933) was an influential German school that combined crafts, decorative arts, and fine arts. Bauhaus architects greatly influenced the International Style, known for simple forms and no decoration. When the Nazi Party rose to power, modern art was called "degenerate art," and the Bauhaus closed in 1933.

-

The Scream; by Edvard Munch; 1893; from the National Gallery of Norway

-

Tower of Blue Horses; by Franz Marc; 1912; from the Bavarian State Painting Collections

-

Composition VII; by Wassily Kandinsky; 1913; from the Tretyakov Gallery

-

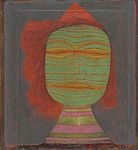

Actor's Mask; by Paul Klee; 1924; from the Museum of Modern Art

Cubism: Breaking Down Reality

Cubism rejected traditional perspective. It created a new way of showing space where objects were seen from multiple viewpoints at once, breaking them into fragments. This showed that form was more important than the subject itself. Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and other Cubist artists were inspired by sculptures from Iberia, Africa, and Oceania.

The critic Guillaume Apollinaire wrote in 1913, "A Picasso studies an object the way a surgeon dissects a corpse." Five years earlier, Picasso and Braque began to reject realistic painting. They created a revolutionary style that looked inside and around objects, showing them in an analytical and impersonal way.

-

Violin and Pitcher; by Georges Braque; 1909–1910; from the Kunstmuseum Basel

-

The Eiffel Tower; by Robert Delaunay; 1911; from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

-

Breakfast; by Juan Gris; 1914; from the Museum of Modern Art

Art Deco: Luxury and Modernity

Art Deco appeared in France as a style of luxury and modernity. It quickly spread worldwide, especially in America, becoming more streamlined in the 1930s. The style was named after the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925. Its lively and imaginative style captured the spirit of the 'roaring 20s' and offered an escape from the Great Depression in the 1930s.

It was influenced by ancient Greek, Roman, African, Aztec, and Japanese art, as well as Futurist, Cubist, and Bauhaus styles. It sometimes mixed with the Egyptian Revival style, especially after the discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, which caused a craze for all things Egyptian. In decorative arts and architecture, Art Deco used low-relief designs and angular patterns. Common materials included chrome, brass, polished steel, aluminum, inlaid wood, stone, and stained glass.

Some important Art Deco artists include the painter Tamara de Lempicka, poster artist Cassandre, and furniture designer Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann.

-

Chrysler Building (New York City), 1930

Surrealism: Dreams and the Subconscious

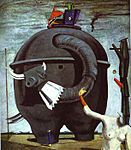

Surrealism grew out of Dada and officially began in 1924 with André Breton's Manifesto of Surrealism. It started as a group of poets and writers in Paris but quickly became an international movement including painters, sculptors, photographers, and filmmakers. Surrealism did not have a big impact on applied arts, architecture, or music, though there are a few examples. The short-lived Metaphysical School (around 1910–1921), with Giorgio de Chirico as its main figure, greatly influenced Surrealism.

Surrealists explored many new techniques, some from Cubism and Dada, others new. These included collage, found objects, and automatic drawing. Two main approaches were used. Automatism was popular early on, seen in the work of artists like André Masson and Joan Miró. Other artists, influenced by Giorgio de Chirico, used more traditional methods to show unfiltered thoughts and strange combinations, like Salvador Dalí and René Magritte. Important artists included Max Ernst, Man Ray, and Frida Kahlo.

With a bit of Dada's disrespect for traditional values, Surrealists explored ideas from Sigmund Freud about the subconscious mind. They aimed for "pure psychic automatism," expressing thoughts without control from reason or moral concerns. Surrealism wanted to show pure thought, uncensored by political, religious, moral, or rational rules.

-

The Elephant Celebes; by Max Ernst; 1921; from Tate Modern

Mid and Late 20th Century Art

After World War II, America became a strong global power. In the 1940s and 1950s, Abstract Expressionism became the first American art movement to have a global impact. This shifted the art world's focus from Europe to New York. Abstract Expressionists were a small group of artists with similar ideas but different styles. They were influenced by Surrealism and believed in spontaneity, freedom of expression, and moving away from American life themes.

One of the most famous artists was Jackson Pollock, known for pouring, flicking, and dripping paint onto huge canvases on the floor. Other artists included Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Mark Rothko.

After World War II, consumerism and mass media grew. As a result, Pop art developed in London and New York. In 1956, the word 'Pop' was used in a collage by Richard Hamilton. Pop art reacted against Abstract Expressionism. It celebrated and commented on consumerism, creating colorful images based on advertising, media, and shopping. It featured film stars, comic strips, and food – things everyone could relate to.

The term Minimalism gained popularity in the 1960s. It described an art style known for its detached and simple approach. Starting in New York, it reacted against Abstract Expressionism but also embraced Constructivist ideas that art should use modern materials. Minimalist artists, mostly sculptors, often used non-traditional materials and industrial production methods. They wanted to challenge assumptions and show familiar objects in new ways. Their artworks had no hidden meanings. They aimed to make viewers rethink art and the space around the forms. Minimalist art often became one with its space. It influenced later Conceptual and Performance art, and helped lead to Postmodernism.

Even though it developed almost 50 years after Marcel Duchamp's ideas, Conceptual art showed that art doesn't always have to be judged by how it looks. It was not a single movement but a broad term covering several art types. It emerged in America and Europe, first defined in New York. Conceptual artists believe that ideas, or concepts, are more important in the modern world than technical skill or beauty. The artwork itself is just a way to present the idea. At its most extreme, Conceptual art might not even have a physical object, using only words to share the idea.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del arte para niños

In Spanish: Historia del arte para niños

- Art of Europe

- Art market

- Art movement

- Art periods

- Ancient art

- History of animation

- History of Asian art

- History of film

- History of literature

- History of music

- History of painting

- History of photography

- History of poetry

- History of theatre

- History of video games

- List of art movements

- List of French artistic movements

- List of music styles

- Timeline for invention in the arts

- Timeline of art

- Western art history

- Women artists

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |