Sican culture facts for kids

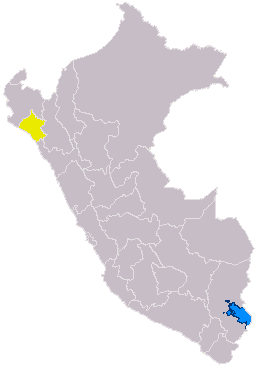

Map of the Sican culture

|

|

| Geographical range | Lambayeque |

|---|---|

| Period | Middle Horizon/ Late Intermediate |

| Dates | c. 750 - 1375 |

| Preceded by | Moche |

| Followed by | Chimor |

The Sican (also called Sicán) culture was an ancient civilization that lived on the northern coast of Peru. They existed from about 750 AD to 1375 AD. Archaeologist Izumi Shimada named this culture. He said "Sican" means "temple of the Moon."

This culture is also known as the Lambayeque culture. This name comes from the Lambayeque region in Peru where they lived. The Sican culture came after the Moche culture. Some experts still debate if they were completely separate groups. The Sican culture is split into three main time periods. These periods are based on changes seen in the things they left behind.

Contents

Where the Sican Lived

Archaeologist Izumi Shimada found the Sican culture in northwestern Peru. He started the Sican Archaeological Project. The Sican people lived after the Moche and before the Inca Empire. The Inca were the big civilization that the Spanish explorers met.

The Sican lived near the La Leche and Lambayeque Rivers. Their ancient sites are found across the Lambayeque region. This includes the Motupe, La Leche, Lambayeque, and Zaña valleys. These are close to the modern city of Chiclayo. Many sites have been found in the Batán Grande area, which is in the La Leche Valley.

The weather during the Sican time was much like it is today. The area has always had cycles of drought and floods. The Sican culture also faced these natural challenges.

Sican Time Periods

The Sican culture is divided into three main periods. These periods show how their culture changed over time.

Early Sican Period (750-900 AD)

The Early Sican period began around 750 AD and ended around 900 AD. We don't have many artifacts from this time. This makes it harder for experts to learn a lot about it. The Sican people were likely descendants of the Moche culture. The Moche culture ended around 800 AD.

Early Sican art shows similar designs to the Moche. They also shared ideas with groups like the Cajamarca, Wari, and Pachacamac. From what we've found, the Sican traded with people far away. They got shells from Ecuador and emeralds from Colombia. They also traded for blue stone from Chile and gold seeds from the Marañón River area.

Around 800 AD, the Sican built the city of Poma. This city was in the Batán Grande area of the La Leche Valley. Not many other Early Sican sites have been found.

Early Sican culture is known for its shiny, black pottery. This style started with the Moche culture before the Sican. This shows how cultures in the region shared ideas. Many of these pots were bottles with a single spout and a loop handle. They often had a human-like bird face at the spout's base. This face had big eyes, a hooked beak instead of a nose, and no mouth. It looked like an early version of the Sican Deity and Sican Lord faces seen later.

Even with shared styles, the Early Sican had its own unique culture. Their changing art, symbols, and burial customs show a new way of thinking. By the late Early Sican period, these changes led to big things. They built huge adobe structures. They also started large-scale metalworking with copper alloys. And they developed the fancy burial traditions that became famous in the Middle Sican period. These changes were seen at sites like Huaca del Pueblo in Batán Grande.

Middle Sican Period (900-1100 AD)

The Middle Sican period lasted from 900 AD to 1100 AD. This was the "golden age" of the Sican culture. Many new cultural ideas appeared during this time. The decline of the Wari Empire allowed local groups to become stronger.

The Middle Sican culture had special features in six areas: art, crafts, burials, trade, religious cities, and government. These features show that the Sican had a strong economy. They also had clear social classes and a powerful religious belief system. Their religion was the foundation of their government, which was led by religious leaders.

Sican Art and Beliefs

Sican art showed real things and was mostly about religion. It often used sculptures and few colors (one to three). This was common in earlier cultures on the north coast of Peru. Sican art took ideas from older cultures like the Wari and Moche. They combined them into a new and unique style. Using old ideas helped make the new Sican religion seem important and real.

The main figure in Sican art was the Sican Deity. This god appeared on almost all Sican art, including pottery, metalwork, and cloth. The god usually had a mask-like face with eyes looking upwards. Sometimes it had bird features like beaks, wings, and claws. These bird features were linked to Naylamp.

Naylamp was a legendary founder of ancient kings in the La Leche and Lambayeque valleys. An old story says Naylamp arrived by sea on a raft. He founded a big city, and his sons started new cities. When Naylamp died, he grew wings and flew to another world.

Middle Sican art kept the same idea for the Sican Deity. Other ancient cultures also had a main male figure with upward-looking eyes. But the symbols around the Sican Deity were special. Symbols of the moon and ocean might show the god's power over sea life and fishermen. Water symbols meant that irrigation and farming were important. Sun and moon symbols showed the importance of balance in life. Pictures of the Sican Deity with knives and trophy heads might mean he controlled human life and the heavens. Experts believe the Sican Deity had power over all natural forces important for life.

Middle Sican art rarely showed humans. This emphasized that the Sican Deity was everywhere. The only exceptions were pictures of the Sican Lord and his helpers. The Sican Lord was a powerful human leader. His image was almost the same as the Sican Deity, but he was shown in natural settings and didn't have bird features. The Sican Lord was probably seen as the god's earthly representative.

Sican Crafts and Technology

The people of Batán Grande were very skilled artisans. Craft production grew greatly during the Middle Sican period. It became one of their most important features. The shiny black pottery from the Early Sican period became even more popular. Metalworking also became very advanced.

Workshops, like one found at Huaca Sialupe, likely made both pottery and metal items. Pottery was used to show political and religious ideas. They made storage jars, decorations, cooking pots, and sculptures of the Deity or animals. Potters probably worked on their own, not in a factory line. Kilns (ovens for firing pottery) were found at Huaca Sialupe. These kilns used local hardwood for charcoal. Experiments showed they could be used for pottery or metalworking.

Metalworking was one of the Sican's greatest achievements. It lasted for almost 600 years at Batán Grande. Some workshops made many different crafts. Metalworking was likely favored by the leaders. This is because only the rich had precious metal objects.

The Middle Sican were great at smelting (melting metal from ore) and using arsenical copper. This type of copper was easier to shape and didn't rust as much as pure copper. Many smelting sites were found in the Lambayeque region. This shows that they had easy access to metal ores and forests for wood. They also had good pottery-making skills and a demand for metal goods from their leaders. Their copper-alloy smelting was not very efficient by today's standards. This might explain why they had so many workshops with multiple furnaces.

Sican Society

The precious metal objects found at Middle Sican sites show how much they produced. Metal items were used by people at all levels of society. Tumbaga, a thin sheet of low-karat gold alloy, was used to cover ceramic pots for lower-ranking leaders. Higher-ranking leaders had high-karat gold alloys. Regular workers only had arsenical copper objects. These metal objects clearly show the different social classes.

No evidence of metalworking has been found at the main Sican sites, like the capital city of Sican. But the precious metal objects were clearly for the elite. From their important sites, the leaders watched over the making of these precious items. These items were used for religious ceremonies or burials.

Sican Burial Customs

Digging up religious sites has taught us a lot about how the Sican buried their dead. These burial practices help us understand how Sican society was organized. Most of this information comes from digs at the Huaca Loro site by Izumi Shimada.

First, the burials at Huaca Loro show the different social classes in Sican society. This is seen in the different types of graves and the items buried with the dead.

The most obvious difference was that common people were buried in simple, shallow graves. These were usually at the edges of the big mounds. The elite (important leaders) were buried in deep tombs under huge mounds. This was seen in the East and West tombs at Huaca Loro.

Second, a person's social status also decided how their body was placed. Bodies could be seated, stretched out, or bent. For example, high-ranking elite bodies were always buried sitting up. Commoners could be buried in any of these positions.

Also, even within the elite tombs, there were differences. The way bodies were grouped showed family and social connections. Studies of the West Tomb showed that women in the south part were related to the main person buried there. They were also related to each other. The women in the north part were not related to each other or to the main person. The pottery in the south part was typical Middle Sican style. The pottery in the north part was Moche style. This suggests that the women in the north might have been from a different group, the Moche. They might have been brought into Sican society after being conquered. This shows how complex elite burials were.

Social class was also shown by the amount and quality of grave goods. The elite East Tomb at Huaca Loro had over a ton of different grave goods. More than two-thirds were objects made of arsenical bronze, tumbaga (low-karat gold), silver, and high-karat gold. Other elite grave goods included precious stones, amber, feathers, textiles, and imported shells. Commoner burials had much fewer grave goods. These were made of less valuable materials. For example, commoners usually had single-spout bottles, plain pottery, and copper-arsenic objects. They did not have the precious metal items of the elite. The power of the Sican elite is shown by how many valuable and exotic goods were in their tombs. It also shows how much time and effort it took to make and get these items.

Building the huge mound at Huaca Loro and preparing the East and West Tombs took careful planning. It also needed a lot of materials, workers, and time. This suggests that the elite controlled society's resources and people.

Second, Sican burial practices suggest there was an elite family line. This family used the new Sican religion to show and keep their power. The Sican elite used burials to show their connection to the gods. The huge size of the mounds built over elite tombs would have amazed Sican citizens. It was a symbol of the divine nature of the people buried below. Colorful murals with religious symbols decorated the temples. This made the ritual space sacred. It also confirmed the connection between the buried elite and the divine. The main person in the East Tomb at Huaca Loro wore a mask just like the Sican Deity. This was another sign of his link to the god.

The building of these huge mounds reminded people of the elite's power. Combined with religious symbols, it helped the Sican elite keep their inherited rights. The rituals performed by living family members also strengthened their family identity. It also reinforced the connection between the divine, the dead, and the living elite.

Sican Trade with Other Lands

The variety of grave goods shows how far the Middle Sican elite's power reached. They received the most and best quality offerings, often from far away. None of the metalworking sites showed evidence of mining nearby. Also, items like spondylus shells, emeralds, and feathers were brought in from other areas.

These materials came mainly from the northern Andes. This included Ecuador (from the Manteno and Milagro cultures), Peru, and Colombia. They might have even traded as far south as the Tiwanaku Empire and east to the Marañón River. The Middle Sican trade networks were huge. They helped spread Sican religion and power beyond their main valleys. They might have also controlled how goods were transported. The Sican could have used llamas, which had been raised on the North Coast since Moche times. Llamas could carry goods long distances.

Sican Religious Cities and Mounds

The Sican culture is known for building religious cities with huge temples. The main religious capital of the Middle Sican was called the Sican Precinct. This T-shaped area included huge mounds like Huaca Loro, El Moscón, Las Ventanas, La Merced, and Abejas. These were built between about 900 and 1050 AD. These pyramid-shaped mounds were used as burial sites for the elite and as places for worship and rituals.

Building these huge mounds needed a lot of materials, workers, and time. This shows that the Sican elite controlled society's resources and people. They were a powerful symbol of the wealth and lasting power of the Middle Sican elite. Their religious government ruled much of the north coast.

Two types of mounds are found in the Lambayeque Valley from the Sican period. The first type was T-shaped. It was a lower mound with a short ramp leading directly to the top. This type was likely used for public rituals. The second type was taller with steep sides and a zig-zag ramp. This ramp led to an enclosed building at the top. This building was probably for private rituals. The mounds also covered and protected the deep tombs of the elite below.

The Sican used a special building method. They built walls with adobe bricks and mortar. Then they filled the spaces with layers of refuse and other materials. Marks on the adobe bricks show which groups donated materials or labor for the temples. This building method allowed them to build huge structures quickly. It also saved labor and materials. This method helped centralize political and religious power. It allowed leaders to plan and complete these massive mounds.

Sican Farming and Canals

While Sican pottery and metalwork are well-known, their farming methods were also important. They might have linked farming to their growing craft production. Experts believe the Sican built canals at Pampa de Chaparri. This was part of a big system that included more mining, growing settlements, and expanding farming.

Along these canals, 39 Middle Sican sites and 76 Late Sican sites were found. Few sites were located directly in the irrigation fields. This shows that the Sican built and used this irrigation system during the Middle Sican period. Building this system, along with social groups linked to canal branches, matches the rapid growth of the Middle Sican. Irrigation was vital for the Sican elite. It allowed them to grow extra food to feed artisans and workers. These workers then supported the elite.

Late Sican Period (1100-1375 AD)

The Late Sican period started around 1100 AD. It ended when the Chimú kingdom of Chimor conquered the Lambayeque region around 1375 AD.

Why Sican and Batán Grande Were Abandoned

Around 1020 AD, a severe drought hit Sican. It lasted for 30 years. At this time, the Sican Deity, who was linked to the ocean and water, was central to their religion. The terrible weather changes were seen as the Sican Deity failing to help the people. Sican ceremonies were supposed to ensure plenty of nature for the people. The elite leaders were the link between the common people and the Sican Deity.

After 30 years of bad weather, the temples that were the heart of Middle Sican religion were burned and abandoned. This happened between 1050 and 1100 AD. Perhaps the power of the elite caused too much anger. Along with the drought that weakened farming, the common people's patience ran out. This forced the leaders to leave Sican to save the people. The damage to Sican was not repaired. More damage came from El Niño floods around 1100 AD.

The New Sican Capital

Since the old capital was burned, a new one had to be built. Túcume (also called "el Purgatorio") became the new Late Sican capital. It was built where the La Leche and Lambayeque Valleys meet. Túcume became the new religious and ceremonial center.

The religious symbols and ideas of the Middle Sican suddenly disappeared. This is when the Sican Deity and Sican Lord stopped appearing in art. This marks the start of the Late Sican period. Other mythical images from the Middle Sican continued. These included felines, fish, and birds. These animals were less important than the Sican Deity before, but they were also linked to older cultures.

Sican material culture, like pottery and metalwork, that wasn't tied to religion or politics, didn't change much. Farming and irrigation were also not affected by the shift in power. This is shown by how Pampa de Chaparri and other large settlements continued to thrive.

Túcume City

Túcume took on the religious importance that Sican had during the Middle Sican period. The idea of mounds and temples continued into the Late Sican. Only the mounds in Batán Grande were associated with the fall of the Middle Sican. The same types of ceremonial and religious artifacts were found at Túcume.

The site grew hugely during its 250 years as the Late Sican capital. By the time the Chimú conquered the Lambayeque region in 1375, Túcume had 26 major mounds and enclosures. The site covers 220 hectares around La Raya Mountain. Túcume is seen as the place where the Sican elite and people came together again, until the Chimú conquest.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Cultura lambayeque para niños

In Spanish: Cultura lambayeque para niños