Tiwanaku Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tiwanaku Polity

Tiahuanaco

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600–1000 | |||||||||||||

Middle Horizon

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital | Tiwanaku, Bolivia | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Puquina | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Horizon | ||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

600 | ||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1000 | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Bolivia Peru Chile |

||||||||||||

The Tiwanaku Polity (also called Tiahuanaco) was a powerful ancient civilization. It was located in western Bolivia, near the southern part of Lake Titicaca. Tiwanaku was one of the most important Andean civilizations. Its influence spread into what is now Peru and Chile. This civilization lasted for about 400 years, from 600 to 1000 AD.

The capital city was also called Tiwanaku. It was a huge, impressive city in the heart of their territory. This area had many large farms with raised fields. These farms likely fed the people living in the city. At its peak around 800 AD, the city of Tiwanaku had between 10,000 and 20,000 people.

Many experts used to think Tiwanaku was a military empire, like the later Inca Empire. However, new research suggests it might have been different. Tiwanaku did not have defensive walls or new weapon technology. There is also no clear proof of a ruling family or formal social classes. There were no state-built roads or markets either.

Instead, Tiwanaku might have been a network of powerful families. They brought people together to build large monuments. These big building projects were like huge parties and ceremonies. This likely attracted people from far away, who came to trade, make offerings, and honor their gods. Tiwanaku became a major pilgrimage spot and one of the largest ancient cities in South America.

Outside their main area, Tiwanaku had colonies in Peru and Chile. People there copied Tiwanaku temples and pottery. Cemeteries in northern Chile had fancy items in the Tiwanaku style. Even with these connections, Tiwanaku leaders probably did not control all the land in between. Their influence was more like "soft power," spreading their culture widely.

The city of Tiwanaku sits very high up, about 3,800 meters (12,500 feet) above sea level. This makes it the highest capital city of the ancient world.

Contents

How Tiwanaku Grew

The site of Tiwanaku started around 110 AD. At that time, many settlements were growing near Lake Titicaca. Between 450 and 550 AD, other big settlements were left empty. This made Tiwanaku the most important center in the region.

Around 600 AD, the city's population grew very fast. Many people likely moved there from the countryside. Large parts of the city were built or rebuilt. New, bigger carved stone statues were put up. Temples were constructed, and a special style of colorful pottery was made in large amounts.

Tiwanaku's influence spread far, shown by their unique pottery. It reached into the Yungas region and affected many other cultures. These included groups in Peru, Bolivia, northern Argentina, and Chile. Some statues at Tiwanaku were brought from other areas. This showed that the gods of Tiwanaku were superior.

The population grew quickly between 600 and 800 AD. Tiwanaku became a major power in the southern Andes. Early guesses said the city covered about 6.5 square kilometers. It was thought to have 15,000 to 30,000 people. Newer studies suggest the city was smaller, about 3.8 to 4.2 square kilometers. The population was likely 10,000 to 20,000. The number of people in Tiwanaku probably changed a lot with the seasons. Many people visited for festivals and work parties.

Hundreds of smaller settlements were found near Lake Titicaca. Some important ones were Lukurmata, Qeya Kuntu, and Khonkho Wankane.

Tiwanaku Colonies

Archaeologists found that Tiwanaku people moved outside their main area. They went into the Moquegua Valley in Peru. After 750 AD, there was a growing Tiwanaku presence there. A ceremonial center was built at the Chen Chen and Omo sites. Digs at Omo showed buildings like those in Tiwanaku. These included a temple and terraced mounds.

Tiwanaku set up several colonies as far as 300 km away. One well-studied colony was in the Moquegua Valley in Peru. This was an agricultural and mining center. It produced copper and silver. Small colonies were also made in Chile's Azapa Valley.

As the population grew, people started to specialize in skills. More artisans worked with pottery, jewelry, and textiles. The Tiwanaku did not have many markets. Instead, leaders controlled the economy. They were expected to give common people what they needed. People had jobs like farming or herding. This led to different social levels. Leaders gained power by controlling extra food. They then shared it with everyone. Controlling llama herds was very important. Llamas carried goods for trade and special items.

Farming Methods

Tiwanaku was located between the lake and dry highlands. This gave them fish, birds, plants, and places for camelids like llamas to graze. Their economy used resources from Lake Titicaca. They also herded llamas and alpacas. They farmed using special raised field systems. The Tiwanaku ate llama meat, potatoes, quinoa, beans, and corn. Because the high-altitude climate changed a lot, storing food was important. They developed ways to freeze-dry potatoes and sun-dry meat.

The Titicaca Basin is very productive. It has steady rainfall because of Lake Titicaca. The lake makes the temperature warmer and the air more humid. To the east, the Altiplano is very dry. The Titicaca Basin also has many water sources, from springs to rivers. Plenty of water was key for Tiwanaku's growth. It gave them fertile land for farming. They used large irrigation projects like raised fields, terraces, and qochas.

Raised Fields

The Tiwanaku developed unique farming methods. One was called "flooded-raised field" agriculture, or suka qullu. These fields were used widely, along with irrigated fields and terraces. Water from the Katari and Tiwanku rivers watered these raised fields. They covered up to 130 square km. In the Titicaca Basin, these were large planting platforms. They were 5–20 meters wide and 200 meters long.

These raised mounds were separated by shallow canals filled with water. The canals kept crops moist. They also absorbed heat from the sun during the day. This heat slowly released at night. This protected plants from the cold frosts common in the region. Over time, the canals were also used to farm edible fish. The mud from the canals was used as fertilizer. This kept the soil rich for crops.

Making suka qullu fields needed a lot of work. But they produced amazing amounts of food. Regular farming in the area yields about 2.4 tons of potatoes per hectare. Modern farming with fertilizers yields about 14.5 tons. But suka qullu farming produced an average of 21 tons per hectare. Modern researchers have brought back the suka qullu technique. In the 1980s, experimental suka qullu fields lost only 10% of their crops during a freeze. Other farms in the region lost 70-90%.

Some researchers think raised fields were not always super productive. Local people stopped using them after experiments ended. Instead, they might have been used for larger plantings. This allowed for two harvests per year. One harvest was for big feasts, and the other for daily food. Organizing this work was important for Tiwanaku families. They had to get volunteers to work the raised fields.

Terraces

Another Tiwanaku farming method was using terraces on hillsides. These terraces got water all year from reservoirs higher up in the mountains. Terraces changed hill slopes into step-like structures. This increased farming space in small areas. They were also less affected by frost at high altitudes. Most importantly, they were good at holding water. Today, modern farming has changed these fields. Walls have been removed for plowing. This has led to more erosion and sloping land.

Qocha

The Tiwanaku also used qochas. These were sunken areas of land, like small basins. They were connected by canals. They were used for farming, grazing, and storing water. You can still see them in the landscape today. Their sunken shape allowed water to collect. This was very helpful during dry seasons, as they kept some moisture. Sometimes these areas were used for several purposes at once.

Why Tiwanaku Declined

Around 1000 AD, Tiwanaku pottery stopped being made. The largest colony (Moquegua) and the capital city were abandoned within a few decades. Some say the end date for Tiwanaku is 1150 AD. But this only counts the raised fields, not the city or pottery.

One idea is that a severe drought made the raised-field systems useless. Food supplies dropped, and so did the power of the leaders. This led to the civilization's collapse. However, this idea is now questioned. Newer studies suggest the drought started *after* the collapse.

This supports other ideas about why Tiwanaku fell. These ideas suggest that problems within their society caused its end. Some parts of the capital city show signs of being purposely destroyed. Giant stone gates, like the Gateway of the Sun, were knocked over and broken. By the end of the Tiwanaku V period, the Putuni complex was burned. Food storage jars were smashed. This shows destruction, then the site was abandoned. Colonies in Moquegua and on Isla del Sol were also left around this time.

Some think the fall of Tiwanaku caused people to move south. This led to changes in Mapuche society in Chile. This might explain why the Mapuche language got many words from the Puquina language. These words include antu (sun), calcu (warlock), and ñuque (mother). Experts like Tom Dillehay suggest that Tiwanaku's decline spread farming techniques to Mapuche lands in south-central Chile. These techniques include the raised fields of Budi Lake and the canalized fields in Lumaco Valley.

... people looking for new suitable places might have caused long-distance ripple effects of both migration and technological diffusion across the south-central and south Andes between c.AD 1100 and 1300 ...

Religion and Beliefs

What we know about Tiwanaku religion comes from archaeology and some myths. These myths might have been passed down to the Incas and the Spanish. The Tiwanaku seem to have worshipped many gods.

The Gateway of the Sun is a large stone structure. Its size suggests other similar buildings were at the site. It was found at Kalasasaya. But because it looks like other gateways at Pumapunku, it might have been part of a series of doorways there. It is famous for its amazing carvings. These carvings are thought to show a main god figure. This god is surrounded by calendar signs or symbols of nature for farming worship.

Another statue in the Gateway of the Sun is believed to be linked to the weather.

a high god of the sky that represented different parts of natural forces. These forces were closely tied to farming in the altiplano: the sun, wind, rain, hail – basically, a god of the atmosphere that directly affects how well crops grow.

It has twelve faces covered by a sun mask. At the bottom are thirty running or kneeling figures. Some scientists think this statue shows the calendar. It might represent twelve months with thirty days each.

Other findings suggest the Tiwanaku worshipped their ancestors. They kept, used, and rearranged mummy bundles and bones. This is similar to what the later Inca did. Later cultures in the area used large "above ground burial chambers for important people," called "chullpas." Smaller, similar structures were found at Tiwanaku.

Experts think the Tiwanaku might have had rituals for the dead, like the Inca. The Akapana East Building shows evidence of ancestor burial. The human remains there seem to be for proper burial, not just for display. The skeletons have cut marks. These were likely made from removing flesh after death. The remains were then bundled and buried, not left out.

The Tiwanaku performed human sacrifices on top of a building called the Akapana. This ritual was likely a way to honor the gods. Research showed that one sacrificed man was not from the Titicaca Basin. This suggests that sacrifices might have been people from other groups.

Buildings and Art

Architecture and Sculpture

Tiwanaku's large buildings are known for their huge, well-made stones. Unlike the later Inca, Tiwanaku stone buildings usually used rectangular blocks. These blocks were laid in neat rows. Their big structures often had complex drainage systems. The drainage systems of the Akapana and Pumapunku buildings had channels made of red sandstone blocks. These blocks were held together by bronze clamps. The clamps for the Akapana were made by hammering metal when it was cold. The clamps for the Pumapunku were made by pouring hot metal into molds. The blocks had flat faces. Grooves allowed them to be moved into place with ropes. The main beauty of the site comes from the carved images and designs on these blocks. There are also carved doorways and giant stone statues.

The stone for Tiwanaku's blocks came from far away. The red sandstone came from a quarry 10 kilometers (6.21 miles) away. This is a long distance, especially since the largest stones weighed 131 metric tons. The green andesite stones, used for the most detailed carvings and statues, came from the Copacabana peninsula. This is across Lake Titicaca. One idea is that these huge andesite stones, weighing over 40 tons, were moved about 90 kilometers (55.92 miles) across Lake Titicaca on reed boats. Then, they were slowly dragged another 10 kilometers (6.21 miles) to the city.

Tiwanaku sculptures are usually blocky, column-like figures. They have big, flat square eyes. They are carved with shallow designs. They often hold ritual objects, like the Ponce Stela. Some images suggest the culture practiced ritual human beheading. As proof, headless skeletons have been found under the Akapana.

Other Arts

The people of Tiwanaku also made pottery and textiles. These had bright colors and stepped patterns. Common textile items included tapestries and tunics. An important pottery item was the qiru. This was a drinking cup that was broken after ceremonies. It was then placed with other items in burials.

Over time, the style of pottery changed. The earliest pottery was "roughly polished, deeply carved brownware and a shiny colorful carved ware." Later, the Qeya style became popular. This pottery included bowls for pouring liquids and vases with round bottoms. The Staff God was a common design in Tiwanaku art.

The carved objects often showed herders, trophy heads, sacrificed people, and felines. These included puma and jaguars. These small, portable objects had religious meaning. They helped spread religion and influence from the main site to other centers. They were made from wood, carved bone, and cloth. They included incense burners, carved wooden snuff tablets, and human portrait vessels. Like those of the Moche, Tiwanaku portraits showed individual features.

One of the best collections of Tiwanaku human portrait vessels was found on Pariti island. This was a pilgrimage center in Lake Titicaca. These vessels show individual human faces. They tell us a lot about Tiwanaku clothing and jewelry styles. Radiocarbon dating showed they were buried between 900 and 1050 AD. They were likely broken as part of a ritual. This happened when local leaders and pilgrims abandoned the island's temple during Tiwanaku's collapse.

Lukurmata

Lukurmata was a large settlement in the Katari valley. It had strong ties to Tiwanaku. It was first built almost two thousand years ago. It grew into a major ceremonial center. After Tiwanaku collapsed, Lukurmata quickly declined. It became a small village again.

Tiwanaku and Wari

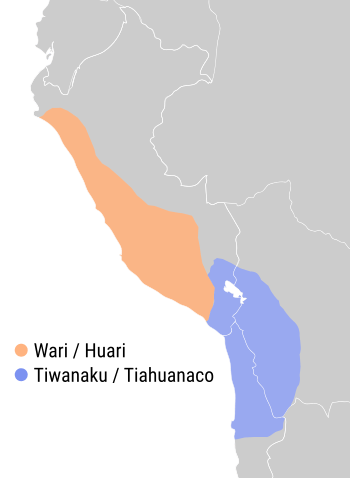

The Tiwanaku shared power during the Middle Horizon with the Wari culture. The Wari were mainly in central and southern Peru. Both cultures rose and fell around the same time. The Wari center was 500 miles north in Peru's southern highlands. We don't know the exact relationship between them. But they clearly interacted, as shown by shared symbols in their art. Many elements from both styles came from the earlier Pukara culture. This culture was in the northern Titicaca Basin.

The Tiwanaku created a strong set of beliefs. They used old Andean symbols that were well-known. They used wide trade routes and shamanistic art. Tiwanaku art had clear, outlined figures with curved lines. It looked natural. Wari art used the same symbols but in a more abstract, straight-lined way. It had a military style.

See also

In Spanish: Cultura tiahuanaco para niños

In Spanish: Cultura tiahuanaco para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |