Architecture of Mesopotamia facts for kids

|

Top: Lamassu from The Gate of Nimrud, Nineveh, approximately 1350 BC;

Centre: The Ziggurat of Ur, approximately 21st century BC; Bottom: Reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate of Babylon, approximately 575 BC in the Pergamon Museum |

|

| Years active | 10th millennium-6th century BC |

|---|---|

The architecture of Mesopotamia refers to the amazing buildings created in the ancient land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. This region, known as Mesopotamia, was home to many different cultures over thousands of years. From the very first permanent homes around 10,000 BC to grand structures in the 6th century BC, Mesopotamians were master builders. They invented urban planning (designing cities), the courtyard house (a home built around an open space), and the famous ziggurats (huge stepped temples). Important people called scribes often worked as architects, planning and managing big building projects for rulers and wealthy families.

Studying ancient Mesopotamian architecture relies on what archaeologists have found. This includes actual building remains, pictures of buildings, and old texts about how they built things. Scholars usually focus on temples, palaces, city walls, and other large buildings. But sometimes, they also study regular homes. Surveys of ancient city sites help us understand how early Mesopotamian cities were laid out.

Exploring Ancient Mesopotamian Buildings

What They Built With

Ancient Mesopotamians mostly used bricks for their buildings. Stone was hard to find in many parts of Mesopotamia. They often didn't use mortar (the glue that holds bricks together) but sometimes used bitumen, a natural tar.

Bricks changed over time. Early bricks were large, like the Patzen bricks (80x40x15 cm) from the Uruk period (around 3600–3200 BC). Later, they used Riemchen bricks (16x16 cm) and Plano-convex bricks (10x19x34 cm) during the Early Dynastic Period (around 3100–2300 BC). Plano-convex bricks were rounded, which made them quicker to make. Builders would lay a row of these bricks sideways every few rows to make the walls stronger.

Most bricks were dried in the sun, not baked in ovens. Sun-dried bricks are not as strong as oven-baked ones. This meant buildings would slowly wear down. So, people would regularly tear down old buildings, flatten the area, and build new ones on the same spot. Over many centuries, this process caused cities to rise higher and higher above the flat land. These raised city mounds are called tells, and you can find them all over the ancient Near East.

To make important buildings last longer, builders added special decorations. They used colorful stone cones, terracotta panels, and clay nails pushed into the mud-brick walls. These not only looked nice but also protected the walls. Sometimes, they even imported special materials like cedar wood from Lebanon, dark stone called diorite from Arabia, and blue lapis lazuli from India.

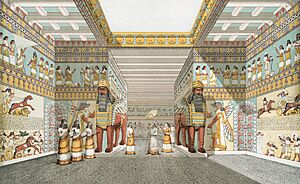

Babylonian temples were huge structures made of crude bricks. They had buttresses (supports) to hold up the walls. Drains, sometimes made of lead, carried away rainwater. The use of bricks led to new ideas like pilasters (flat columns attached to a wall) and columns. Walls were often brightly colored with frescoes (paintings on wet plaster) and shiny enamelled tiles. Some walls were even covered with zinc or gold! Assyrians copied many Babylonian building styles, even using bricks in areas where stone was common. This was because bricks were essential in the marshy lands of Babylonia.

Decorating Their Buildings

Later, Assyrian builders started using more stone. They decorated the walls of their palaces with carved and colored stone slabs, instead of just painting them. These carvings, called bas-reliefs, showed scenes that were strong and simple under King Ashurnasirpal II. They became more detailed and realistic under Sargon II, and very refined under Ashurbanipal.

In Babylonia, where stone was scarce, people became very skilled at carving small objects like gems. They also made beautiful jewelry, like gold earrings and bracelets. They were also known for their amazing embroideries and rugs.

Planning Amazing Cities

The Sumerians were the first people to truly plan and build cities. They were very proud of this! The famous story of Epic of Gilgamesh starts by describing the city of Uruk with its huge walls, streets, markets, temples, and gardens. Uruk became a model for other cities across Western Asia.

Cities grew partly by design and partly naturally. Walls, the main temple area, canals, and main streets were all planned. The smaller areas for homes and shops grew more organically, but still within the planned city limits. We know a lot about how Sumerian cities grew because they kept records of land sales.

A typical city had different areas: homes, mixed-use (shops and homes), commercial (markets), and civic (government buildings). The main temple complex was usually at the heart of the city, slightly off-center. This temple often existed before the city itself and was the starting point for the city's growth. Areas near the city gates had special religious and economic importance.

Cities also included farmland with small villages around them. A network of roads and canals connected the city to these farms. There were three types of roads: wide processional streets for important events, public streets for everyone, and private narrow alleys. Canals were even more important than roads for moving goods and people.

Homes for Everyone

The materials for Mesopotamian houses were similar to what we use today, but simpler. They used reeds, stone, wood, ashlar, mud brick, mud plaster, and wooden doors. These materials were found naturally around the cities, though wood was not always plentiful. Most houses were made of mudbrick, mudplaster, and poplar wood.

Houses came in different shapes: some were three-part, some round, and some rectangular. Many had a central square room with other rooms attached. The size and materials varied greatly, suggesting people built their own homes. The smallest rooms might not have belonged to the poorest people. It's possible the poorest built homes from materials like reeds outside the city walls, but we have little proof. Houses could also include shops, workshops, storage rooms, and even places for livestock.

The design of houses developed from earlier Ubaid houses. The most common type was the courtyard house, which is still used in Mesopotamia today. This house, called é in Sumerian, faced inward towards an open courtyard. The courtyard helped keep the house cool by creating air currents. All the rooms opened into this courtyard. The outside walls usually had only one door connecting the house to the street. To go from the street to the courtyard, you had to turn 90 degrees through a small entrance room. This design kept private spaces hidden from the street. A typical Sumerian house was about 90 square meters.

How Houses Were Built

Simple houses could be made by tying bundles of reeds together and sticking them into the ground. More complex houses had stone foundations and were built with mudbricks. Wood, ashlar blocks (cut stone), and rubble were also used. Mudbricks were made from clay and chopped straw, packed into molds, and dried in the sun. Walls were covered with mud plaster, and roofs were made of mud and poplar wood. In the Ubaid period, walls sometimes had fire clay pressed into them or artwork painted on them. Roofs could also be made from palm wood planks covered with reeds. Stairs, made of brick or wood, connected the roof to the house.

Baked bricks were very expensive, so they were only used for fancy buildings. Doors and door frames were made of wood, or sometimes ox-hide. Doors between rooms were often very low, so people had to bend down to pass through. Houses usually had no windows, or if they did, they were made of clay or wooden grilles. Floors were typically dirt. Mesopotamian houses often crumbled and needed frequent repairs.

House Designs and Rooms

In the Ubaid period, houses often had three parts. They featured a long central hallway with smaller rooms on both sides. This central hallway might have been used for dining and group activities. Ubaid houses varied, with some having more valuable items than others. They could also be connected to other houses. The design of Ubaid houses was similar to Ubaid Temples.

During the Uruk period, houses came in various shapes, including rectangular and round. Some Mesopotamian houses had only one room, while others had many, sometimes including basements. Around 3000 BCE, courtyards became a key feature of Mesopotamian architecture. These courtyards were surrounded by thick-walled halls, likely used as reception rooms for guests. Most houses probably had an upper story for dining, sleeping, and entertaining. People might have grown vegetables or performed religious rituals on their roofs. Ground floors were used for shops, workshops, storage, and keeping livestock. One room often served as a sanctuary.

Furniture and Comfort

Ancient Sumerian houses had decorated stools, chairs, jars, and bathtubs. Wealthier people even had toilets and proper drainage systems. Some houses might have had altars in the center, possibly dedicated to the gods or important ancestors.

Grand Palaces of Kings

Palaces first appeared during the Early Dynastic I period. They started small but grew larger and more complex as rulers gained more power. A palace was called a 'Big House' (ekallu in Akkadian) where the king (lugal or ensi) lived and worked.

Early Mesopotamian palaces were huge complexes, often beautifully decorated. Examples are found in the Diyala River valley at places like Khafajah and Tell Asmar. These palaces from the third millennium BC were more than just homes. They included workshops for craftsmen, food storage, ceremonial courtyards, and even small shrines. For instance, the "giparu" at Ur, where the priestesses of the Moon god Nanna lived, was a massive complex with many courtyards, sanctuaries, burial chambers, and a banquet hall. A similar grand palace was found at Mari in Syria, from the Old Babylonian period.

Assyrian palaces from the Iron Age, especially at Nimrud, Khorsabad, and Nineveh, are famous for their Assyrian palace reliefs. These were detailed carvings on stone slabs (called orthostats) that covered the walls. They showed religious scenes or stories of the kings' military victories and building projects. Gates and important entrances were guarded by huge stone sculptures of mythical figures like lamassu (human-headed winged bulls) and winged genies. These palaces also had large and small courtyards. The king's throne room usually opened onto a huge ceremonial courtyard where important meetings and ceremonies took place.

Many ivory furniture pieces were found in Assyrian palaces. This shows that they traded a lot with North Syrian kingdoms. Bronze bands decorated the wooden gates of major buildings, but most were stolen when the empire fell. The Balawat Gates are a rare surviving example.

Sacred Temples

Temples were often built before cities even existed. They grew from small, single-room buildings into huge complexes over 2,500 years of Sumerian history. Sumerian temples, along with fortifications and palaces, used advanced building methods like buttresses, recesses (indented parts of a wall), and half columns.

Over time, as a temple decayed, it was ritually destroyed. A new, larger, and more detailed temple was then built on its foundations. The E₂.abzu temple at Eridu is a great example of this process. Many temples had inscriptions carved into them, like the one at Tell Uqair. Palaces and city walls appeared much later than temples, during the Early Dynastic Period.

The design of a Sumerian temple reflected their beliefs about the universe. They believed the world was a flat disc surrounded by a saltwater ocean, both floating on a freshwater sea called apsu. Above them was a dome-shaped sky that controlled time. A "world mountain" connected all three layers. The temple's job was to be this "world mountain," a meeting place between gods and humans. The idea that high places were sacred meeting points was very old, going back to the Neolithic age.

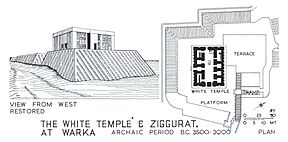

Temples were rectangular, with their corners pointing towards the main compass directions. This symbolized the four rivers flowing from the world mountain. It also helped priests use the temple roof as an observatory to keep track of time. The temple was built on a low platform of rammed earth. This platform represented the sacred mound of land, called dukug ('pure mound'), that emerged from the water at the beginning of creation.

The doors on the long side of the temple were for the gods, and the doors on the short side were for people. This was called the "bent axis approach." Anyone entering had to make a ninety-degree turn to face the statue of the god at the end of the central hall. This bent axis approach was an improvement from earlier Ubaid temples, which had a straight path. It was also a feature of Sumerian houses. An offering table was placed in the center of the temple where the paths crossed.

During the Uruk Period, temples had different layouts: tripartite (three-part), T-shaped, or a combination. The tripartite plan, inherited from the Ubaid period, had a large central hall with two smaller halls on either side. The entrance was on the short side, and the shrine was at the end of the long side. The T-shaped plan was similar but had an extra hall at one end, perpendicular to the main hall. Temple C from the Eanna district of Uruk is a classic example of temple design.

Temple designs became much more varied during the following Early Dynastic Period. They still kept features like cardinal orientation, rectangular plans, and buttresses. But now they included new things like courtyards, walls, basins, and barracks. The Sin Temple in Khafajah is a good example from this time, designed around a series of courtyards leading to a cella (the main room of the temple).

The high temple was a special type of temple dedicated to the city's main god. It served as a storage and distribution center, and also housed the priests. The White Temple of Anu in Uruk is a typical high temple, built very high on a platform of mud-brick. In the Early Dynastic period, high temples began to include a ziggurat, which was a series of platforms creating a stepped pyramid. These ziggurats might have inspired the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel.

Towering Ziggurats

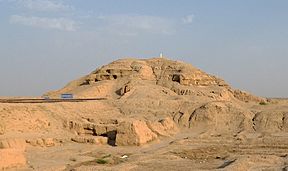

Ziggurats were huge, pyramidal temple towers. They were first built in Sumerian City-States and later in Babylonian and Assyrian cities. There are 32 known ziggurats in or near Mesopotamia. Notable ones include the Great Ziggurat of Ur in Iraq and Chogha Zanbil in Iran. Ziggurats were built by the Sumerians, Babylonians, Elamites, and Assyrians as monuments to their local religions. The earliest ziggurats were raised platforms from the Ubaid period (fourth millennium BC), and the latest date from the 6th century BC. Unlike many pyramids, the top of a ziggurat was flat. The stepped pyramid style began near the end of the Early Dynastic Period.

Built in receding layers on a rectangular, oval, or square base, the ziggurat was a pyramidal structure. Sun-baked bricks formed the core, with outer layers of fired bricks. These outer bricks were often glazed in different colors, which might have had astrological meanings. Kings sometimes had their names carved on these glazed bricks. Ziggurats had between two and seven tiers, with a shrine or temple at the very top. Ramps on one side or a spiral ramp from base to top provided access to the shrine. Some people think ziggurats were built to look like mountains, but there isn't much evidence to prove this.

Classical ziggurats appeared in the Neo-Sumerian Period. They featured clear buttresses, shiny brick coverings, and a slight curve in their walls (called entasis). The Ziggurat of Ur is the best example of this style. Another change in temple design during this period was a straight path to the temple, instead of the bent-axis approach.

Ur-Nammu's ziggurat at Ur was planned with three stages, but only two remain today. The entire mudbrick core was originally covered with baked bricks set in bitumen. The first stage's covering was 2.5 meters thick, and the second stage's was 1.15 meters thick. Each baked brick was stamped with the king's name. The sloping walls of the stages had buttresses. A triple monumental staircase led to the top, meeting at a portal between the first and second stages. The first stage was about 11 meters high, and the second rose about 5.7 meters. Archaeologists usually reconstruct a third stage, topped by a temple. At the Chogha Zanbil ziggurat, archaeologists found huge reed ropes running through the core, tying the mudbrick mass together.

Important architectural remains from early Mesopotamia include temple complexes at Uruk (4th millennium BC), temples and palaces from the Early Dynastic period in the Diyala River valley (like Khafajah and Tell Asmar), and Third Dynasty of Ur remains at Nippur and Ur. Later sites include palaces and temples from the Middle and Late Bronze Age, and Iron Age palaces and temples in Assyria (Nimrud, Khorsabad, Nineveh), Babylonia (Babylon), and other regions. We know about houses mostly from Old Babylonian remains at Nippur and Ur. Texts like Gudea's cylinders (late 3rd millennium) and royal inscriptions from the Iron Age tell us about building construction and rituals.

Gardens and Water Features

Text records show that planned open spaces were part of cities from the very beginning. The Epic of Gilgamesh describes one-third of Uruk being set aside for orchards. A similar planned open space was found at Nippur. Empty lots (called kišubbû in Akkadian) were also an important part of the city landscape.

Outside the cities, Sumerian farming with irrigation created some of the first garden designs in history. A garden (sar) was typically 144 square cubits with a canal around its edge. This design of an enclosed square garden became the basis for the later paradise gardens of Persia.

In Mesopotamia, fountains were used as far back as the 3rd millennium BC. An early example is a carved Babylonian basin from around 3000 BC, found at Girsu. An ancient Assyrian fountain found in the Comel River gorge had basins cut into solid rock, stepping down to the stream. Water flowed into these basins from small conduits.

Images for kids

-

King Ashurnasirpal's throneroom relief showing Ashur hovering above the tree of life.

-

Sargon II in his royal chariot, trampling a dead or dying enemy, part of a war scene from Dur-Sharrukin. Iraq Museum

-

Ruins from a temple in ancient Nippur, said to be the site for the meeting of Sumerian gods, as well as the place that man was created.

See also

- Ancient Mesopotamian units of measurement

- Abbasid architecture

- Achaemenid architecture

- List of cities of the ancient Near East

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |