Chaitya facts for kids

A chaitya (say "chai-tya") is a special kind of prayer hall or temple found in Indian religions, especially Buddhism. It's often a large hall with a stupa (a dome-shaped structure holding relics) at one end. This end is usually rounded, like an apse in some churches. The roof is often high and curved.

While a chaitya technically refers to the stupa itself, people often use the word to mean the entire hall where the stupa is located. Outside India, in places like Nepal, Cambodia, and Indonesia, Buddhists use "chaitya" for smaller, stupa-like monuments. In Thailand, a stupa is called a chedi. In Jainism and Hinduism, a chaitya can mean any temple, sacred place, or monument.

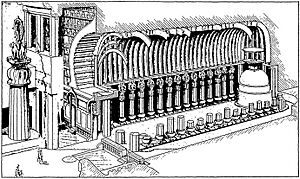

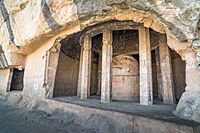

Most of the oldest chaitya halls we can still see today are carved directly into rock. Experts believe these stone halls copied earlier ones made from wood and other plants, which haven't survived. The curved, ribbed ceilings in the rock-cut halls look just like timber roofs. In older examples, real wooden ribs were added to the stone ceilings. At the Bhaja Caves and the "Great Chaitya" of the Karla Caves, you can still see these original wooden ribs. Later, even the ribs were carved from stone. Sometimes, parts made of wood, like screens or balconies, were added to the stone buildings. All the surviving chaityas have a similar basic design, but they changed over many centuries.

These halls are tall and long, but not very wide. At the far end, you'll find the stupa, which is the main focus for worship. A very important ritual was Parikrama, which means walking around the stupa. So, there's always clear space for people to walk around it. The end of the hall is rounded, similar to an apse in Western buildings. There are always columns along the side walls, reaching up to where the curved roof begins. Behind these columns, there's a passage, creating aisles and a central nave. This allows for the ritual walk, either right around the stupa or along the passage behind the columns.

Outside, there's usually a porch, which is often beautifully decorated. The entrance is fairly low. Above the entrance, there's often a gallery. Most of the natural light, apart from a little from the entrance, comes from a large, horseshoe-shaped window above the porch. This window's curve matches the curve of the roof inside. The overall look is quite similar to smaller Christian churches from the Early Medieval period, even though early chaityas were built many centuries earlier.

Chaityas are often found at the same sites as viharas. Viharas are very different buildings. They have a rectangular central hall with a low ceiling and small rooms opening off it, often on all sides. These rooms were used for living, studying, and praying. Viharas were key buildings in Buddhist monasteries. Large sites usually have several viharas for every chaitya.

Contents

What the Word "Chaitya" Means

The word "Caitya" comes from an old Sanskrit word meaning "heaped-up." It refers to a mound, pedestal, or even a "funeral pile." It means some kind of sacred structure. The word has taken on different meanings in various places. For example, "caityavṛkṣa" means a sacred tree.

In early Jainism writings, caitya meant ayatanas or temples where monks stayed. It also referred to where Jain idols were placed in a temple. But generally, it was a symbol for any temple. Some texts call them arhat-caitya or jina-caitya, meaning shrines for a holy person (Arhat or Jina). Old Jain sites like Kankali Tila near Mathura show Caitya-trees, Caitya-stupas, and special arches with meditating Tirthankaras (Jain spiritual teachers).

The word caitya also appears in the Vedic literature of Hinduism. In early Buddhist and Hindu writings, a caitya is any 'piled up monument' or 'sacred tree' where people could meet or meditate. Scholars like Jan Gonda say that in Hindu texts, caitya can mean any "holy place, place of worship," a "memorial," or any "sanctuary" for people. According to professors Robert E. Buswell and Donald S. Lopez, who study Buddhism, the term caitya in Sanskrit means a "mound, sanctuary or shrine," in both Buddhist and non-Buddhist settings.

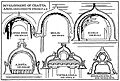

The "Chaitya Arch" as a Decoration

The "chaitya arch," also called gavaksha (Sanskrit for "cow's eye"), is the large window above the entrance of a chaitya hall. This arch shape often appears as a smaller decoration, repeated many times. Later versions of this design continued to be used in Hindu and Jain art, long after Buddhists stopped building actual chaitya halls.

When used as decoration, it can become a fancy frame around a circular or half-circular shape. This shape might contain a sculpture of a person or a head. You can see an early example at the entrance to Cave 19 at the Ajanta Caves (around 475–500 CE). Here, four rows of decoration use repeated "chaitya arch" designs on a plain band. There's a head inside each arch.

How Chaityas Developed

The earliest chaitya halls we know about date back to the 3rd century BCE. They usually had a rounded (apsidal) shape and were either carved into rock or built as freestanding structures.

Rock-cut Chaitya Halls

The oldest surviving spaces that look like chaitya halls are from the 3rd century BCE. These are the rock-cut Barabar Caves (Lomas Rishi Cave and Sudama Cave). They were carved during the time of Ashoka for the Ajivikas, a religious group that was not Buddhist. Many experts believe these caves became the "model for the Buddhist caves of the western Deccan," especially the chaitya halls carved between 200 BCE and 200 CE.

Early chaityas held a stupa and had space for monks to gather and worship. This showed an early difference between Buddhism and Hinduism. Buddhism liked group worship, while Hinduism often focused on individual worship. The first chaitya halls were carved into living rock as caves. They served as a symbol and place for the Buddhist community (sangha) to gather.

The earliest rock-cut chaityas, like the freestanding ones, had an inner circular room with pillars around the stupa. This created a circular path. There was also an outer rectangular hall for the worshippers. Over time, the wall between the stupa and the hall was removed. This created a single apsidal hall with columns around the central area (nave) and the stupa.

The chaitya at Bhaja Caves is probably the oldest surviving chaitya hall, built in the 2nd century BCE. It has a rounded hall with a stupa. The columns lean inward, copying wooden columns that would have been needed to hold up a roof. The ceiling is barrel vaulted with old wooden ribs still in place. The walls are polished in the style of the Maurya Empire. The front of the cave had a large wooden facade, which is now gone. A big horseshoe-shaped window, called the chaitya-window, was placed above the arched doorway. The whole entrance area was carved to look like a multi-story building with balconies and windows. It even had sculptures of men and women watching the scene below. This made it look like an ancient Indian mansion. This, and a similar facade at the Bedse Caves, shows how "architectural decoration in India is made up of small models of large buildings."

At Bhaja, and in other chaityas, the entrance marked the line between the sacred space inside and the everyday world outside. The stupa inside the hall could not be seen from outside. Around the 1st century CE, the focus of worship changed from just the stupa to also include images of Gautama Buddha. Chaityas were usually part of a larger monastery complex, called a vihara.

The most important rock-cut complexes include the Karla Caves, Ajanta Caves, Ellora Caves, Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves, Aurangabad Caves, and the Pandavleni Caves. Many pillars in these caves have carved tops, often showing a kneeling elephant on bell-shaped bases.

-

Rock-cut hall, Sudama, Barabar Caves, built in 257 BCE by Ashoka.

-

The window at the chaitya Cave 10, Ellora, around 650 CE.

-

Stupa inside Cave 10, Ellora, the last chaitya hall built. The Buddha image now dominates the stupa.

Freestanding Chaitya Halls

Some freestanding chaitya halls made of strong materials like stone or brick have survived. The oldest ones are from about the same time as the first rock-cut caves. There are also some ruins and foundations. For example, a circular one from the 3rd century BCE, the Bairat Temple, had a central stupa surrounded by 27 wooden pillars. This was then enclosed by a circular brick wall, creating a path around the stupa. Other important remains of built chaityas include those at Guntupalle and Lalitgiri.

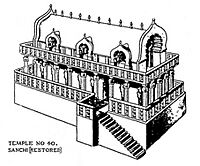

A rounded (apsidal) building in Sanchi, called Temple 40, is also partly from the 3rd century BCE. It's one of the first freestanding temples in India. Temple 40 has parts from three different time periods. The earliest part is from the Maurya age, likely around the same time the Great Stupa was built. An inscription even suggests it might have been built by Bindusara, the father of Ashoka. The original 3rd century BCE temple was built on a high rectangular stone platform. It was a rounded hall, probably made of wood. It burned down sometime in the 2nd century BCE. Later, the platform was made larger and reused to build a hall with fifty columns. Some of these columns have inscriptions from the 2nd century BCE.

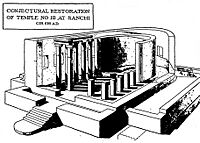

The base and rebuilt columns of Temple 18 at Sanchi were likely finished with wood and thatch. This temple is from the 5th century CE, possibly rebuilt on older foundations. It stands next to Temple 17, a small temple with a flat roof and a lower hall (mandapa) at the front. This basic design became common for both Buddhist and Hindu temples later on. Both types were used in the Gupta Empire by both religions.

The Trivikrama Temple, also known as "Ter Temple," is now a Hindu temple in Ter, Maharashtra. It was originally a freestanding building with a rounded end, typical of early Buddhist chaitya designs. This part of the building is still standing, but it's now at the back. A flat-roofed hall (mandapa) was probably added from the 6th century CE when the temple became Hindu. The rounded part seems to be from the same time as a large rounded temple found in Sirkap, Taxila, which dates to 30 BCE-50 CE. It would have been built under the Satavahanas. The front of the rounded temple is decorated with a chaitya-arch, similar to those found in Buddhist rock-cut caves. The Trivikrama Temple is thought to be the oldest standing building in Maharashtra.

Another Hindu temple that was once a Buddhist chaitya is the small Kapoteswara temple at Chezarla in Guntur district. Here, the main room is straight at both ends, but its roof is a rounded brick vault, built using a technique called corbelling.

-

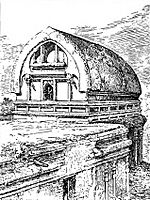

Sanchi, Temple 18, from the apse end. Partly rebuilt.

-

Excavated remains of a structural chaitya at Lalitgiri, Odisha, India.

The End of the Chaitya Hall

It seems the last rock-cut chaitya hall to be built was Cave 10 at Ellora, in the first half of the 7th century. By this time, the role of the chaitya hall was being taken over by the vihara. Viharas had started to include shrine rooms with Buddha images (which could easily be added to older viharas). They largely took over the function of gathering places. The stupa itself was replaced as the main focus for worship and meditation by the Buddha image. In Cave 10, like in other late chaityas (for example, Cave 26 at Ajanta), there's a large seated Buddha statue at the front of the stupa. Other than this, the inside of the hall isn't much different from examples built centuries before. But the shape of the windows on the outside changed a lot. They almost completely stopped copying wooden architecture. Instead, they showed a decorative style around the chaitya arch that became very popular in later temple decoration.

The last stage of freestanding chaitya hall temples might be seen in the Durga temple, Aihole, from the 7th or 8th century. This temple has a rounded end at the sanctuary, with three layers: the sanctuary enclosure, a wall beyond it, and an open walkway with pillars all around the building. This walkway was the main space for parikrama (walking around). Above the rounded sanctuary, which is now a room with a doorway, rises a Shikhara tower. This tower is quite small compared to later ones. The main hall (mandapa) has a flat roof. We don't know how long chaitya halls made of plant materials continued to be built in villages.

Similarities to Other Buildings

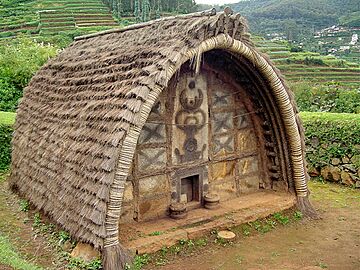

- Toda Huts

People have often noticed how much chaityas look like the traditional huts still made by the Toda people in the Nilgiri Hills. These are simple huts built with bent wicker to create arch-shaped roofs. However, the models for the chaitya were probably much larger and more complex structures.

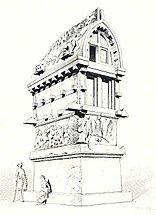

- Lycian Tombs

The barrel-vaulted tombs of Lycia in Asia Minor from the 4th century BCE, like the tomb of Payava, look very similar to the Indian chaitya design. Indian chaityas started at least a century later (around 250 BCE, with the Lomas Rishi Caves). This suggests that the designs of the Lycian rock-cut tombs might have traveled to India. Or, both traditions might have come from a common, older source.

Early on, James Fergusson, in his book "Illustrated Handbook of Architecture", said that "In India, the form and construction of the older Buddhist temples resemble so singularly these examples in Lycia." Ananda Coomaraswamy and others also noted that "Lycian excavated and monolithic tombs at Pinara and Xanthos on the south coast of Asia Minor look somewhat like the early Indian rock-cut caitya-halls." This is one of many shared features between early Indian and Western Asian art.

The Lycian tombs, from the 4th century BCE, are either freestanding or carved into rock. They are barrel-vaulted sarcophagi (stone coffins) placed on a high base. They have architectural features carved in stone to look like wooden structures. There are many rock-cut versions that look like the freestanding ones. One of the freestanding tombs, the tomb of Payava, from Xanthos, is from 375-360 BCE and can be seen at the British Museum. Both Greek and Persian influences can be seen in the carvings on the sarcophagus. The similarities with Indian Chaityas, even in small details like the "same pointed form of roof, with a ridge," are discussed further in the book The cave temples of India. Fergusson suggested a "connection with India" and some kind of cultural exchange across the Achaemenid Empire. Overall, the idea that Lycian designs for rock-cut monuments were transferred to India is considered "quite probable."

Anthropologist David Napier has also suggested the opposite: that the Payava tomb came from an ancient South Asian style. He even thought the man named "Payava" might have been a Graeco-Indian named "Pallava."

Chaityas in Nepal

In Nepal, the word "chaitya" has a different meaning. A Nepalese chaitya is not a building. It's a shrine monument that looks like a stupa on top of a base. They are often very decorated. They are usually placed outdoors, often in religious areas, and are typically about four to eight feet tall. People from groups like the Sherpas, Magars, Gurungs, Tamangs, and Newars build them to remember someone who has died. The Newar people of the Kathmandu Valley started adding images of the four Tathagatas (important Buddhas) on the four sides of the chaitya, mainly after the 12th century. They are built with beautifully carved stone and mud mortar. People say they represent the five basic elements: earth, air, fire, water, and space.

Chaityas in Cambodia

In old Cambodian art, chaityas were used as markers for sacred sites. They were usually made in sets of four and placed at the four main directions (north, south, east, west) on the edge of the site. They usually look like pillars, often topped with a stupa, and have carvings on their sides.

Images for kids

-

Outside the chaitya at Cave 19, Ajanta Caves, also with four zones using small repeated "chaitya arch" motifs.

See also

- Cetiya

- Index of Buddhism-related articles

- Burmese pagoda

- Pagoda festival

- Pagoda

- Stupa