Chavín culture facts for kids

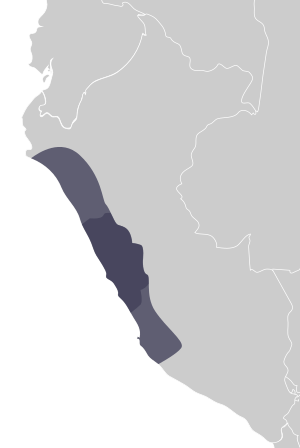

The area of the Chavín civilization, as well as areas with Chavín cultural influences

|

|

| Period | Early Horizon |

|---|---|

| Dates | 900 – 200 BCE |

| Type site | Chavín de Huántar |

| Preceded by | Kotosh |

| Followed by | Moche, Lima, Nazca |

The Chavín culture was an ancient civilization that lived in the northern Andes mountains of Peru. They existed from about 900 BCE to 200 BCE. This culture is named after Chavín de Huántar, which is the main place where their ancient objects have been found.

The Chavín people lived in the Mosna Valley, where the Mosna and Huachecsa rivers meet. This area is high up in the mountains, about 3,150 meters (10,335 feet) above sea level. Their influence spread to other groups living along the coast. The Chavín culture is a key part of the Early Horizon period in Peru. During this time, people became more religious, started using special pottery for ceremonies, improved their farming, and developed skills in working with metals and making textiles.

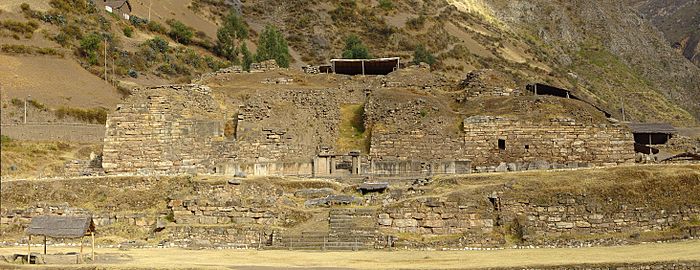

The most famous place for the Chavín culture is Chavín de Huántar. It is located in the Ancash Region of Peru. People believe it was built around 900 BCE and was a very important religious and political center for the Chavín people. Today, it is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Contents

What Did the Chavín People Achieve?

The Chavín people were very skilled builders and artists. Their main building was the Chavín de Huántar temple. This temple shows how clever they were at building in the mountains of Peru.

To stop the temple from flooding during the rainy season, the Chavín built a smart drainage system. They made several canals under the temple to carry water away. They also understood how sound works! When water rushed through these canals during the rainy season, it made a loud roaring sound, like a jaguar. Jaguars were sacred animals to them.

The temple was built using white granite and black limestone. These stones were not found nearby. This means that Chavín leaders organized many workers to bring these special materials from far away. They might have also traded for them with other groups.

The Chavín culture also knew a lot about metallurgy (working with metals). They were good at soldering (joining metals) and controlling heat. They used early methods to create beautiful gold objects. They had learned how to melt metal and use it to join pieces together.

The Chavín people also raised animals like llamas. These animals were used to carry things, for their wool, and for meat. They made ch'arki, which is dried llama meat (like jerky). This was an important item that llama herders traded, and it was a main source of income for the Chavín people.

They were also successful farmers. They grew crops like potatoes, quinoa, and maize (corn). They even built irrigation systems to help their crops grow better.

What Language Did They Speak?

We don't know what language the Chavín people spoke because they didn't have a written language. It's likely that their language is now extinct. Some experts think it might have been an early form of Quechuan. They believe this because Quechuan languages have very regular grammar, which would have helped different communities communicate across mountain ranges. However, other experts believe Proto-Quechuan languages appeared later, around 1 CE.

How Was Their Architecture?

Chavín de Huántar was the starting point for the second large civilization in the central Andes. This was mainly because of the amazing buildings at the site, which are seen as great engineering achievements. The site has both inside and outside architecture.

- Inside architecture includes galleries, hallways, rooms, staircases, air shafts, and drainage canals.

- Outside architecture includes plazas (open squares), platform mounds, and terraces.

The "Old Temple" was built first, from about 900 to 500 BCE. The "New Temple" was added later, from about 500 to 200 BCE. What's interesting is that there aren't many houses, everyday items, weapons, or storage areas found at the site. This shows that the buildings were mainly focused on temples and what was inside them.

The main part of Chavín de Huántar was built in at least 15 stages. Each stage involved building more of the 39 known galleries. In the earliest stage, buildings were separate. Later, during the Expansion Stage, they connected buildings to form a U-shape around open spaces. The galleries became very detailed during this time. In the Black and White Stage, all the main plazas were built. As construction finished, the galleries became more standard. By the end, the buildings formed U-shaped plazas with a central line that also went through the Lanzón (a famous stone carving).

Builders made changes during all stages to keep access to the inside parts of the site. They wanted to make sure that the sacred elements, like the Lanzón, remained visible. The inside parts were designed as one big plan and connected closely with the outside parts.

The Lanzón Gallery was made from an older building that was later covered to become an inside space with a stone roof. The Lanzón carving itself might have been there even before the roof was built. In general, the galleries followed careful building plans, showing a lot of design and effort. It was important for architects to keep these galleries working over time. The galleries were designed to be confusing, with no windows, dead ends, sharp turns, and changes in floor height. This was meant to disorient people walking through them.

The Chavín builders used a mix of balanced (symmetrical) and unbalanced (asymmetrical) designs. Staircases, entrances, and patios were often placed in the center. In the later stages, when centering wasn't possible, they built symmetrical pairs of structures. However, the outside buildings were often asymmetrical to each other.

The main building materials were quartzite and sandstone, white granite, and black limestone. They used layers of quartzite blocks for the main platforms. White sandstone and white granite were used for other parts, and they were almost always cut and polished. Granite and black-veined limestone were used for almost all the carved stone art at the site. Granite was also used a lot in building the Circular Plaza.

The stone-faced platforms were made by carefully filling them with rectangular quartzite blocks in level layers. They often built new platforms directly on top of fallen stones from older buildings, without much effort to clear away the old debris.

Chavín Art

The Chavín culture created the first widely recognized art style in the Andes. Chavín art can be divided into two periods:

- The first period matches the building of the "Old Temple" at Chavín de Huántar (around 900–500 BCE).

- The second period matches the building of the "New Temple" (around 500–200 BCE).

Chavín art is known for its complex symbols and "mythical realism." You often see humans and animals interacting in their art (ceramics, pottery, sculptures). This shows how the Chavín people felt connected to the spirit world.

Other symbols in Chavín art give us clues about their culture. For example, there's evidence that they used psychoactive plants in their rituals. The San Pedro Cactus often appears in their art, sometimes held by people, suggesting its use in ceremonies.

Chavín pottery from the coast often comes in two types: carved, many-sided pots and round, painted pots. Chavín art often uses a technique called contour rivalry. This means that lines in the art can be seen as different things depending on how you look at them. The art was meant to be hard to understand, probably only for the high priests of the Chavín religion, who could read the complex and sacred designs. The Raimondi Stele is a great example of this. However, the pottery doesn't always show the same art style as the sculptures.

Chavín art decorates the temple walls and includes carvings, sculptures, and pottery. Artists showed animals from other regions, like jaguars and eagles, instead of just local plants and animals. The feline (cat) figure is very important in Chavín art. It had a deep religious meaning and appears on many carvings and sculptures. Eagles are also common.

There are three main examples of Chavín art: the Tello Obelisk, tenon heads, and the Lanzón.

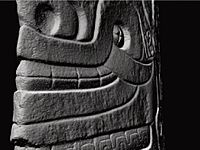

- Tello Obelisk is a tall, rectangular stone pillar with carvings on all four sides. It shows two creatures that look similar. Some think they are "cat-dragons" or caymans. This large carving might tell a creation myth.

- Tenon heads are found all over Chavín de Huántar. They are huge stone carvings of jaguar heads with fangs that stick out from the top of the inside walls. They are one of the most famous images of the Chavín civilization.

- The Lanzón is perhaps the most impressive Chavín artifact. It's a 4.53-meter (14.86-foot) long carved granite pillar inside the temple. It goes through an entire floor and ceiling. It's carved with a fanged god, which is a common image in Chavín art. The Lanzón is in a gallery inside the Old Temple. The way the chamber is designed, with only four openings, means you can only see parts of the Lanzón at a time. This was done on purpose.

Where Did Chavín Influence Reach?

The Chavín culture had a wide influence on nearby civilizations. This was partly because Chavín de Huántar was located at a trade crossroads between the deserts and the Amazon jungle.

For example, at Pacopampa, a site north of Chavín de Huántar, the main temple was rebuilt in a style typical of Chavín culture. At Caballo Muerto, a coastal site, a mud-brick structure was added to the main temple during renovations, showing Chavín influence. In the modern-day Lima region, the site of Garagay has Chavín-style art, including a head with mucus coming from the nostrils. At Cerro Blanco, Chavín pottery has been found.

It seems that warfare was not a big part of Chavín culture. Archaeological findings show that Chavín centers did not have strong defenses. Also, warriors are not shown in their art, which is different from earlier art at Cerro Sechín. It's possible that social control was kept through religious beliefs. Also, the ability to control water resources might have helped leaders keep people in line. The difficult climate and land outside their managed areas made it hard for farmers to leave the culture. Evidence of fighting has only been found at sites from the same time that were *not* influenced by Chavín culture. This suggests those other groups might have been defending themselves from Chavín cultural spread.

The Chavín style and period spread widely, from Piura on the far north coast to Paracas on the south coast. It also reached from Chavín in the northern highlands to Pucará in the southern highlands.

How the Chavín Culture Developed

Some experts thought that the Chavín culture grew more complex because they started growing a lot of maize (corn) and had extra food. However, studies of human bones from Chavín sites show that their diet was mostly made up of foods like potatoes and quinoa. Maize was not a main part of their diet. Potatoes and quinoa were better suited for the Chavín environment because they are more resistant to frost and uneven rainfall in high-altitude areas. Maize would not have grown well in such conditions.

Earlier Cultures Before Chavín

The Kotosh Religious Tradition came before the Chavín culture at several sites. Some elements from Kotosh, like their pottery styles, show connections to the Chavín culture.

Even before Kotosh, there was the Wairajirca Period, when the first pottery appeared. The Mito tradition was even older, a time before pottery, but people still built public buildings.

Stages of Chavín Culture

The Chavín culture itself had three main pottery stages, which show how the culture developed:

- Urabarriu (900 to 500 BCE): In this first stage at Chavín de Huántar, a few hundred people lived in two small areas, not right next to the ceremonial center. People hunted many different animals, especially deer, and started hunting and using camelids. They ate clams and shellfish from the Pacific Ocean, as well as guinea pigs and birds. They also grew some maize and potatoes. The pottery from this stage was heavily influenced by other cultures. It seems pottery was made in many different places because there wasn't a high demand from the spread-out population.

- Chakinani (500 to 400 BCE): This was a short transition period. During this time, people moved closer to the ceremonial center. The Chavín started to domesticate llamas and hunted fewer deer. There's also evidence of more trade with outside groups.

- Jarabarriu (400 to 250 BCE): This was the final stage. The Chavín population grew a lot. The way people lived changed to a more city-like pattern, with a main center in the valley and smaller communities in the higher areas around it. People started to have specialized jobs, and there was more social differentiation. People living east of Chavín de Huántar might have had less importance than those closer to the ceremonial center. During this phase, a lot of different pottery was made, and the Chavín pottery style became more distinct. Smaller communities also started making their own pottery.

Who Held Power in Chavín Society?

At Chavín, power was held by a small group of important people, called the elite. They were believed to have a special connection to the gods. Shamans, who were religious leaders, gained their power and authority from claiming this divine connection. The community wanted to connect with the divine. When power is not equal, traditions are often shaped by those in charge. Shamans could use clever ways to change traditions and gain more authority. Big changes were happening during the Chavín period.

Experts believe that the more effort put into convincing people through rituals, objects, and settings, the more likely it was that leaders knew they were acting in their own interest and were guiding the changes. Archaeological evidence shows examples of new interpretations of beliefs, the use of special plants, and changes to the landscape. It also shows the complex planning and building of stone-walled galleries.

The idea of "invented tradition" means bringing together new elements to make something seem like an old tradition. This can be seen in the architecture at Chavín de Huántar, which combined many aspects from other cultures to create a unique, yet traditional, look.

The huge amount of landscape changes at Chavín de Huántar for temple rebuilding shows that someone or a group had the power to plan these changes and convince others to do the work. The large constructions at this site support the idea that power was not equal.

Finally, the planning and building of the stone-walled galleries suggest a system with different levels of power. Besides needing to command many workers, the galleries show unique planning. They had only one entrance, which was unusual for the time when rooms usually had many ways in and out. The art on the walls of the stone galleries is very complex. This complexity suggests that only a select few people could understand the art. These people would act as translators for the few others who were allowed to see the galleries. The limited access, both physically and symbolically, to the stone-walled galleries supports the idea of a shaman elite at Chavín de Huántar. It seems that the shamans and those who planned and built the ceremonial center carefully planned how to gain and keep their authority.

Religion and Rituals

Religion and its practices were deeply connected to the social, political, and economic life of the Chavín society. We don't fully understand all their rituals, but we can learn a lot from their buildings, offerings, and art, especially their pictures. Over time, rituals became more private and exclusive, as seen in how they used and developed ritual spaces and buildings. Religious leaders played a big role in how the site was designed and how rituals were performed.

Sacred Spaces: Buildings for Rituals

The buildings at Chavín de Huántar had religious meaning. The sacred spaces and structures were clearly used for rituals and religious purposes. Understanding the design of Chavin de Huántar helps us see how the builders wanted people to have a specific experience. The site was designed to affect the senses, especially sight and touch. It was about how people perceived the space. Sacred areas, like plazas, were designed to make people feel something rather than just look at them.

The people who designed and built Chavín's architecture are thought to be priests or religious leaders. The layout of the site also shows that high-ranking officials were present. These leaders guided the architecture to keep the ritual parts of their culture important. They did this through the details of each building, making sure that people taking part in rituals felt like they were truly experiencing religious events. The sacred ritual spaces were built with many different workers, and no single person was in charge of the entire construction.

The ritual architecture of the Chavín is similar to other ancient Andean coastal buildings. The earliest buildings at the site were plastered, rectangular rooms. One of these later held the Lanzón. The architecture allowed for many different ritual practices within these spaces. This makes experts wonder if Chavín served as a ceremonial center for many different groups. The buildings, materials, and offerings might have been inspired by other cultures. The ritual spaces themselves had a hierarchy, showing the order of the universe and society.

The Chavín buildings and spaces used for rituals were built to create an experience. Two important ritual spaces were the Old Temple and the New Temple. Both temples had pathways and places to worship gods on their north and south sides. The temples, especially the Old Temple, had gods carved into stone. The temples were U-shaped, surrounding a circular plaza. They also had ceremonial rooms and sacred hearths (fireplaces). Plazas were also important structures used for rituals. The Circular Plaza and the Square Plaza were key places for ceremonies.

Inside the Chavín site, there was a structure with rooms and galleries. Archaeologists think these were "ritual chambers" for various ceremonies, possibly including fire ceremonies. Large underground spaces, like stone-lined galleries that are often like mazes, run through the main platforms and mounds. These are thought to have been centers for religious activity where ceremonies took place, involving both audiences and participants.

The difference between the open spaces of the plazas and the small, enclosed spaces of the Chavín galleries shows how ritual spaces changed over time, moving from public to more private practices. The gallery spaces are key to understanding the Chavín rituals.

In 2018, archaeologists led by John Rick discovered that these underground galleries were also the final resting place for some people, possibly the temple's builders. Their bodies were found face-down and covered by rocks. John Rick suggested that these people might have been sacrificed, though this is not yet confirmed. This discovery gives us some clues about where the Chavín people buried their dead, though it might not have been a common burial practice. If it's confirmed that they were sacrificed, it would also support the idea that the galleries were used for rituals.

The sizes of the sacred spaces allowed for different numbers of people. Outside spaces like the plazas could hold more people for rituals. The Square Plaza could have held about 5,200 people, and the Circular Plaza about 600. Inside spaces, like the galleries or hallways, could only hold a small number. For example, in the Lanzón gallery in the Old Temple, only about 15 people could attend a ceremony, and in the canal entries, only 2 to 4 people.

Ritual Practices and Ceremonies

Chavín rituals were not entirely new; they had strong connections to practices from other Andean societies. The rituals at the site might show the diverse practices that existed at that time.

The Chavín wanted more followers, but they also wanted to create a central authority and bring different societies together. Ritual practices changed over time, showing both public and private religion. There was also a growing distance between those performing the rituals and those watching in public ceremonies. People who visited the site are called "participants" by archaeologists. This change didn't happen suddenly, as old practices were often used as rituals developed.

There is debate about whether Chavín practices were more hierarchical (with clear levels of power) or heterarchical (with more equal power). Some archaeologists believe that for rituals to be most successful, they needed to be more private. But other evidence shows that central areas reflected a lack of hierarchy in ritual practice, and that the society used open spaces to show a more inclusive religious experience. This suggests that ritual practice might have been both, and it shows their openness to other religious institutions, rituals, and traditions. Regardless, it is widely accepted that the Chavín were inclusive in their ritual practices.

Important parts of Chavín rituals included processions, offering valuable materials (like exotic items), and using water. For example, broken pieces of obsidian and mirror fragments have been found as offerings. Other ceremonies included smashing pots and fire ceremonies held in certain areas of the Chavín site. Artifacts in the temples show the practice of offerings. Pottery, for instance, was believed to be offerings brought by pilgrims. Conch shells, used as trumpets, were also found. Art suggests that processions were a key part of Chavín rituals. Shamans also performed other rituals, such as divination (predicting the future), observing the sky, calculating calendars, and healing.

Music also played a role in Chavín rituals. Strombus shell trumpets were found at Chavín sites. These trumpets were stored underground and are believed to have been used by ritual performers, who would play them while moving through the underground galleries.

Religious Art

Religious art reflects the Chavín people's surroundings and daily lives, including their religious practices. Art showed that there were certain gods in Chavín culture, as well as symbols related to rituals. Stone art, for example, indicates that processions were important to Chavín rituals. Other art included images of jaguars and creatures that were a mix of humans with felines, birds, and crocodile features. These were likely made by shamans.

Deities (Gods)

Gods were a very important part of Chavín religious practice. The most central god was the Lanzón. It was believed to be a founding ancestor with special powers to give advice. The Lanzón statue was carved into a large stone and found inside the Old Temple. It was the main focus of the Old Temple. It is carved from stone and stands 4.5 meters (14.8 feet) tall. The Lanzón is also shown in the New Temple.

Other gods reflected the Chavín people's natural world and the sky. These included figures like crested eagles, hawks, snakes, crocodiles (caymans), and jaguars. They were often mixed with human features, becoming hybrid creatures. The Chavín were also interested in showing opposites and combining them, such as men and women, the sun and moon, and the sky and water in the same image.

Religious Figures

Religious figures played a key role in Chavín religious rituals. Generally, people higher up in society managed the ritual activities and brought Chavín rituals into the community. Shamans are most commonly understood to be the main religious figures. Leaders managed daily tasks, and authority came from a small group, rather than one single leader. They lived close to the temple in residential buildings. Leaders showed their skills in understanding the supernatural world and their ability to influence it, which made them stand out as religious figures.

Images for kids

-

The sandeel monolithic has a length of 5 meters and represents a Chavín deity. It is located in the Ancient Temple in Chavín de Huántar.

-

Tenon head embedded in one of the walls of the temple of Chavín de Huántar.

-

The ceremonial centre of Kuntur Wasi, according to the latest archaeological research would be an prechavín expression associated to felínico Chavín cult. Cajamarca Region.

-

Remains of Pacopampa, another prechavín expression of Formative stage period but remained an important ceremonial centre like Chavín de Huántar, also located in the Cajamarca Region.

-

Model of the archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar.

-

The llama was the main representative of Chavín livestock.

See also

In Spanish: Cultura chavín para niños

In Spanish: Cultura chavín para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |