Mark Rothko facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mark Rothko

|

|

|---|---|

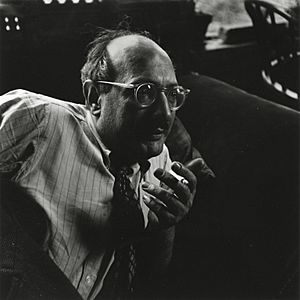

Mark Rothko, Yorktown Heights, c. 1949. Brooklyn Museum, by Consuelo Kanaga.

|

|

| Born |

Markus Yakovlevich Rothkowitz

September 25, 1903 |

| Died | February 25, 1970 (aged 66) New York City, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Yale University |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Abstract expressionism, color field |

| Spouse(s) | Edith Sachar (1932–1943) Mary Alice "Mell" Beistle (1944–1970) |

| Patron(s) | Peggy Guggenheim, John de Menil, Dominique de Menil |

Mark Rothko (born Markus Yakovlevich Rothkowitz; September 25, 1903 – February 25, 1970) was a famous Latvian-American abstract painter. He is best known for his "color field" paintings. These artworks show large, soft-edged rectangles of color. He created these unique paintings from 1949 until his death in 1970.

Rothko didn't say he belonged to any one art group. However, he is often linked to the American Abstract Expressionist movement. This was a modern art style where artists expressed emotions through abstract forms. He moved from Russia to Portland, Oregon with his family. Later, he settled in New York City. His early art often showed city scenes. During the 1940s, influenced by World War II, Rothko's art changed. He explored myths and Surrealism to show feelings of sadness. By the end of the 1940s, he began painting canvases with pure color. These colors became the rectangular shapes he used for the rest of his life.

Later in his career, Rothko painted large murals for three different projects. The Seagram murals were meant for a fancy restaurant in the Seagram Building. But Rothko didn't like the idea of his art being just decoration for rich diners. He returned the money and gave the paintings to museums, including the Tate Modern. The Harvard Mural series was given to a dining room at Harvard University. Over time, their colors faded because of the paint he used and sunlight. These murals have since been fixed using special lighting. Rothko also created 14 paintings for the Rothko Chapel. This is a special building in Houston, Texas, open to people of all faiths.

Rothko lived simply for most of his life. But after he died in 1970, his paintings became very valuable. In 2021, one of his artworks sold for $82.5 million.

Contents

Early Life and Moving to America

Childhood in Latvia

Mark Rothko was born in Daugavpils, Latvia. At that time, Latvia was part of the Russian Empire. His father, Jacob Rothkowitz, was a pharmacist and a thoughtful person. He wanted his children to have a non-religious upbringing. Rothko said his father was strongly against religion. Growing up, Rothko felt afraid because Jewish people were often blamed for problems in Russia.

Even though his family didn't have a lot of money, they were well-educated. Rothko's sister remembered, "We were a reading family." Mark spoke Lithuanian Yiddish, Hebrew, and Russian. When he was five, his father decided to return to his Jewish faith. Mark, the youngest of four children, was sent to a religious school called a cheder. There, he studied the Talmud. His older siblings had gone to public schools.

Journey to the United States

Jacob Rothkowitz worried that his older sons would be forced to join the Imperial Russian Army. So, he moved to the United States. Mark stayed in Russia with his mother and older sister, Sonia. They arrived at Ellis Island in late 1913. From there, they traveled across the country to join Jacob and his brothers in Portland, Oregon.

Just a few months later, Jacob died from colon cancer. This left the family without money. Sonia worked at a cash register. Mark sold newspapers in one of his uncle's warehouses. His father's death made Rothko turn away from religion. After mourning his father for almost a year at a local synagogue, he promised never to go to one again.

School Days in Portland

Rothko started school in the United States in 1913. He quickly moved from third to fifth grade. In June 1921, he finished high school with honors at Lincoln High School in Portland. He was 17 years old.

He learned English, his fourth language. He also became active in the Jewish community center. There, he was good at political discussions. At that time, Portland was a hub for revolutionary ideas in the U.S. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a workers' union, was active there.

Rothko grew up around meetings for radical workers. He went to IWW meetings, where he heard speakers like Bill Haywood and Emma Goldman. These experiences helped him become a strong speaker. He later used these skills to defend his art. When the Russian Revolution began, Rothko organized debates about it. Even with strict political rules, he wanted to become a labor union organizer.

Time at Yale University

Rothko received a scholarship to Yale University. But after his first year in 1922, the scholarship wasn't renewed. He worked as a waiter and delivery boy to pay for his studies. He felt Yale was too focused on rich people and was unfair. Rothko and a friend, Aaron Director, started a funny magazine called The Yale Saturday Evening Pest. It made fun of the school's serious and old-fashioned style. At the end of his second year, Rothko left Yale. He didn't go back until 46 years later, when he received an honorary degree.

Becoming an Artist

Discovering Painting

In the fall of 1923, Rothko found work in New York's garment district. One day, he visited a friend at the Art Students League of New York. He saw students drawing a model. Rothko said this moment was the start of his life as an artist.

He later joined the Parsons The New School for Design. One of his teachers was Arshile Gorky. Rothko felt Gorky watched his students too closely. That same fall, he took classes at the Art Students League. These were taught by Max Weber, a Cubist artist who had been part of the French avant-garde. Weber was seen as a "living history book" for students who wanted to learn about Modernism. Under Weber, Rothko began to see art as a way to show feelings and spiritual ideas. Rothko's paintings from this time show Weber's influence. Years later, Weber saw Rothko's art and praised it, which made Rothko very happy.

New York Art Scene

Moving to New York put Rothko in a lively art world. Modern painters often showed their work in galleries. The city's museums were also a great place for a young artist to learn. Early influences on Rothko included German Expressionism, the surrealist art of Paul Klee, and paintings by Georges Rouault.

In 1928, Rothko and other young artists showed their work at the Opportunity Gallery. His paintings were dark, moody, and expressive. They showed indoor scenes and city views. Critics and other artists generally liked them. To earn more money, Rothko started teaching drawing, painting, and clay sculpture to children in 1929. He taught at the Center Academy of the Brooklyn Jewish Center for over twenty years.

Meeting Other Artists

In the early 1930s, Rothko met Adolph Gottlieb. Gottlieb, along with Barnett Newman, Joseph Solman, Louis Shanker, and John Graham, was part of a group of young artists around Milton Avery. According to artist Elaine de Kooning, Avery showed Rothko that being a professional artist was possible. Avery's abstract nature paintings, with their strong forms and colors, greatly influenced Rothko. Soon, Rothko's paintings began to look like Avery's, for example, Bathers, or Beach Scene (1933–1934).

Rothko, Gottlieb, Newman, Solman, Graham, and Avery spent a lot of time together. They vacationed at Lake George, New York, and Gloucester, Massachusetts. They painted during the day and discussed art in the evenings. In 1932, during a visit to Lake George, Rothko met Edith Sachar, a jewelry designer. They married later that year. The next summer, Rothko had his first solo art show at the Portland Art Museum. It mostly featured drawings and watercolors. For this show, Rothko did something unusual: he displayed his young students' work next to his own.

His family didn't understand why Rothko wanted to be an artist. This was especially true during the difficult economic times of the Great Depression. The Rothkowitz family had faced serious money problems. They were confused by Rothko's lack of concern for money. They felt he was not helping his mother by not finding a more profitable job.

First New York Show

Back in New York, Rothko had his first solo show on the East Coast at the Contemporary Arts Gallery. He showed fifteen oil paintings, mostly portraits, along with some watercolors and drawings. The oil paintings especially caught the attention of art critics. Rothko's use of rich color fields went beyond Avery's influence. In late 1935, Rothko joined with other artists to form "The Ten". This group wanted to show that American painting was more than just realistic pictures.

Rothko's reputation grew among his fellow artists. He was part of the Artists' Union, which hoped to create a city art gallery for artists to show their own work. In 1936, the group exhibited in France and received good reviews. One reviewer noted that Rothko's paintings "display authentic coloristic values." In 1938, they had a show in New York to protest the Whitney Museum of American Art. They felt the Whitney focused too much on local, traditional art. During this time, Rothko, like many other artists, found work with the Works Progress Administration.

Developing His Unique Style

Changes in His Art

Rothko's art style changed over time. His early period (1924-1939) featured realistic art, often city scenes, with an impressionist feel. His middle, "transitional" years (1940-1950) included phases of abstract art inspired by myths, then "biomorphic" shapes (like living forms), and finally "multiforms." Multiforms were canvases with large areas of color. World War II influenced Rothko's transitional decade. He wanted to find new ways to express sadness in art. During this time, he was influenced by ancient Greek writers like Aeschylus and the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche.

In his mature or "classic" period (1951-1970), Rothko consistently painted rectangular areas of color. He wanted these paintings to be like "dramas" that would make viewers feel strong emotions.

In 1936, Rothko started writing a book, which he never finished. It was about how children's art was similar to modern paintings. He believed that modern art, influenced by early art, was like children's art. He wrote, "Tradition of starting with drawing in academic notion. We may start with color." Rothko was already using fields of color in his watercolors and city scenes. His style was moving towards his famous later works. But despite this new focus on color, Rothko then explored other artistic ideas. He began a period of surrealist paintings, inspired by myths and symbols.

Inspiration from Mythology

Rothko felt that modern American painting had reached a dead end. He wanted to explore subjects beyond city and nature scenes. He looked for topics that would fit his growing interest in shape, space, and color. The world crisis of war made this search urgent. He wanted new subjects to have a social impact but also go beyond current political symbols. In an essay from 1948, Rothko wrote that ancient artists used "monsters, hybrids, gods and demigods" to explain things. He felt modern people found similar ideas in political movements. For Rothko, "without monsters and gods, art cannot enact a drama."

Rothko's use of mythology to comment on current events wasn't new. Rothko, Gottlieb, and Newman read and discussed the ideas of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. They were especially interested in theories about dreams and shared human ideas (archetypes). They saw mythological symbols as images that exist in human thought, going beyond specific history and culture. Rothko later said his art changed after studying "dramatic themes of myth." He even stopped painting in 1940 to read Sir James Frazer's book on mythology, The Golden Bough, and Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams.

Nietzsche's Influence

Rothko's new artistic ideas tried to meet modern people's spiritual needs. A key influence on Rothko during this time was Friedrich Nietzsche's book The Birth of Tragedy. Nietzsche said that Greek plays helped people deal with the fears of life. Rothko's goal was no longer just to explore new art topics. From then on, his art aimed to fill the spiritual emptiness of modern people. He believed this emptiness came partly from a lack of myths. Nietzsche wrote that myths are like "unnoticed omnipresent demonic guardians" that help a young person grow and understand life. Rothko believed his art could release hidden energies, which were once tied to myths and rituals. He saw himself as a "mythmaker" and said that "the exhilarated tragic experience is for me the only source of art."

Many of his paintings from this period show a contrast between violent, wild scenes and calm, civilized ones. He used images mainly from Aeschylus's Oresteia plays. Some of Rothko's paintings from this time include Antigone, Oedipus, The Sacrifice of Iphigenia, Leda, and The Furies. He also used images from the Bible, like Gethsemane and The Last Supper. He even used Egyptian (Room in Karnak) and Syrian (The Syrian Bull) myths. After World War II, Rothko felt his titles limited the deeper meaning of his paintings. To allow viewers to interpret them freely, he stopped naming his paintings and just used numbers.

Moving Away from Surrealism

In 1943, Rothko and his wife Edith separated. Rothko returned to Portland and then traveled to Berkeley, where he met artist Clyfford Still. They became close friends. Still's abstract paintings greatly influenced Rothko's later work. In the fall of 1943, Rothko returned to New York. He met art dealer Peggy Guggenheim, but she was not keen on his art at first. Rothko's solo show at Guggenheim's The Art of This Century Gallery in late 1945 didn't sell many paintings. Critics also gave it mixed reviews. During this time, Rothko was inspired by Still's abstract landscapes of color. His style began to move away from surrealism. Rothko's experiments with hidden symbols in everyday forms had run their course.

Rothko's painting Slow Swirl at the Edge of the Sea (1945) shows his new move towards abstract art. Some think it's about his relationship with his second wife, Mary Alice "Mell" Beistle, whom he married in 1945. Others see hints of Botticelli's The Birth of Venus, which Rothko saw in 1940. The painting uses soft grays and browns. It shows two human-like shapes in a swirling mix of forms and colors. The straight rectangular background hints at Rothko's later pure color paintings. This painting was finished in the year World War II ended.

Even after he stopped his "Mythomorphic Abstractionism," the public still mostly knew Rothko for his surrealist works throughout the 1940s. The Whitney Museum included them in its annual contemporary art exhibit from 1943 to 1950.

The "Multiform" Paintings

In 1946, Rothko started creating what art critics call his "multiform" paintings. Rothko himself never used this term, but it describes these paintings well. Some of them, like No. 18 and Untitled (both 1948), are not just transitional but fully developed. Rothko said these paintings had a more natural structure. He saw them as complete expressions of human feeling. For him, these blurred blocks of different colors, without landscapes, people, or symbols, had their own life. They had a "breath of life" that he felt was missing in most realistic paintings of the time. They were full of possibilities, while his experiments with mythological symbols had become old. The "multiforms" led Rothko to his famous style of rectangular color areas. He continued to paint in this style for the rest of his life.

During this important time, Rothko was impressed by Clyfford Still's abstract color fields. Still's work was partly influenced by the landscapes of his home in North Dakota.

In 1947, Rothko and Still thought about starting their own art school. In 1948, Rothko, Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, Barnett Newman, and David Hare founded the Subjects of the Artist School. They held public lectures with speakers like Jean Arp and John Cage. But the school didn't make enough money and closed in 1949. Even though the group broke up, the school was a lively place for new art ideas. Rothko also started writing articles for two new art magazines, Tiger's Eye and Possibilities. He used these articles to talk about the art world and his own work and ideas. These writings show how he removed realistic elements from his paintings.

Rothko described his new method as "unknown adventures in an unknown space." He said it was free from "direct association with any particular, and the passion of organism." This meant his art and his own self were now full of possibilities. This was shown by creating changing, unclear shapes.

In 1947, he had his first solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery. In 1949, Rothko was fascinated by Henri Matisse's Red Studio, which the Museum of Modern Art bought that year. He later said it was another key inspiration for his abstract paintings.

Later Years and Famous Art Projects

His Signature Style

Soon, the "multiforms" became Rothko's signature style. By early 1949, he showed these new works at the Betty Parsons Gallery. For critic Harold Rosenberg, the paintings were amazing. After painting his first "multiform," Rothko stayed at his home in East Hampton. He invited only a few people, including Rosenberg, to see the new paintings. Finding his final style came during a difficult time for the artist. His mother, Kate, had died in October 1948.

Rothko began using symmetrical rectangular blocks of two or three colors. These colors were often opposite or contrasting, but they worked well together. For example, "the rectangles sometimes seem barely to coalesce out of the ground, concentrations of its substance. The green bar in Magenta, Black, Green on Orange, on the other hand, appears to vibrate against the orange around it, creating an optical flicker." For the next seven years, Rothko only painted large, tall canvases with oil paints. He used very large designs to make the viewer feel overwhelmed, or, in his words, "enveloped within" the painting. Some critics thought the large size was to make up for a lack of deeper meaning.

Rothko even suggested that viewers stand very close to the canvas, about eighteen inches away. He wanted them to feel a sense of closeness, wonder, and a connection to something beyond themselves.

Many of the "multiforms" and early signature paintings use bright, lively colors, especially reds and yellows. By the mid-1950s, Rothko started using dark blues and greens. Many critics felt this color change showed a growing sadness in Rothko's personal life.

Rothko's painting method involved applying a thin layer of binder mixed with pigment directly onto untreated canvas. He then painted very thin oils onto this layer. This created a rich mix of overlapping colors and shapes. His brushstrokes were quick and light, a method he used until his death. He became very skilled at this, especially in the paintings for the Chapel. Without realistic figures, the drama in a late Rothko painting comes from the contrast of colors shining against each other. His paintings can be seen as a kind of musical arrangement. Each color variation balances another, but they all exist within one overall structure.

Rothko used several unique techniques that he tried to keep secret. Studies showed he used natural things like egg and glue, as well as man-made materials like acrylic resins and other chemicals. One goal was to make the paint layers dry quickly without colors mixing. This allowed him to add new layers on top. In 1968, Rothko's health declined, and he began painting most of his large works with acrylic paint instead of oils.

Travels and Growing Fame

Rothko and his wife traveled in Europe for five months in early 1950. He had not been to Europe since his childhood in Latvia. He didn't return to his homeland but visited important art collections in England, France, and Italy. The frescoes by Fra Angelico in the San Marco monastery in Florence impressed him the most. Fra Angelico's spiritual art and focus on light appealed to Rothko. He also related to the financial struggles the artist faced.

Rothko had solo shows at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1950 and 1951. He also had shows in Japan, São Paulo, and Amsterdam. The 1952 "Fifteen Americans" show at the Museum of Modern Art featured abstract artists like Jackson Pollock. This show also caused a disagreement between Rothko and Barnett Newman. Newman accused Rothko of trying to exclude him from the show. As the group of abstract artists became more successful, they started arguing about who was best. When Fortune magazine called a Rothko painting a good investment in 1955, Newman and Clyfford Still called him a sell-out. Still asked Rothko to return paintings he had given him. Rothko was very upset by his former friends' jealousy.

During the 1950 Europe trip, Rothko's wife, Mell, became pregnant. On December 30, back in New York, she gave birth to a daughter, Kathy Lynn. They called her "Kate" after Rothko's mother.

The Seagram Murals

In 1958, Rothko received his first major mural project. The company Joseph Seagram and Sons had just finished their new Seagram Building skyscraper. Rothko agreed to create paintings for the building's new luxury restaurant, the Four Seasons. This was a big challenge for Rothko. It was the first time he had to design a series of paintings for a specific, large indoor space. Over the next three months, Rothko completed forty paintings in dark red and brown. He changed his usual horizontal format to vertical to match the restaurant's tall columns, walls, and windows.

The next June, Rothko and his family traveled to Europe again. They visited Rome, Florence, Venice, and Pompeii. In Florence, he saw Michelangelo's Laurentian Library. He was inspired by the library's entrance hall. He said, "the room had exactly the feeling that I wanted ... it gives the visitor the feeling of being caught in a room with the doors and windows walled-in shut." He was also influenced by the dark colors of the murals in the Pompeiian Villa of the Mysteries. After Italy, the Rothkos went to Paris, Brussels, and London. In London, Rothko studied Turner's watercolors at the British Museum.

Back in New York, Rothko and his wife visited the nearly finished Four Seasons restaurant. He was upset with the restaurant's atmosphere, which he found too fancy and not right for his art. Rothko refused to continue the project and returned the money he had received. Seagram had wanted to honor Rothko by choosing him, so his refusal was unexpected.

Rothko kept the paintings in storage until 1968. He had known about the restaurant's luxury design and its wealthy customers beforehand. So, his reasons for backing out are still a bit of a mystery. He wrote to a friend, "it seemed clear to me at once that the two were not for each other." Rothko was a strong-willed person and never fully explained his feelings about the incident. The final Seagram Murals are now in three places: London's Tate Britain, Japan's Kawamura Memorial Museum, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. This event was the main idea for John Logan's 2009 play Red.

In October 2012, Black on Maroon, one of the Seagram paintings, was damaged with black ink at Tate Modern. It took 18 months to restore the painting. The ink went deep into the canvas, causing "significant damage."

Harvard Murals

Rothko received a second mural project for a room at Harvard University's Holyoke Center. He made 22 sketches and painted ten large canvases. Six were sent to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and five were hung. There was a set of three paintings on one wall and two single panels opposite them. His goal was to create a special environment for a public space. Harvard President Nathan Pusey had the paintings hung in January 1963. They were later shown at the Guggenheim. During installation, Rothko felt the room's lighting harmed the paintings. Despite adding special shades, the paintings were removed by 1979. Because some red pigments faded easily, they were put in dark storage and only shown sometimes. From November 2014 to July 2015, the murals were displayed in the newly renovated Harvard Art Museums. A new color projection system was used to make up for the faded colors.

The Rothko Chapel

The Rothko Chapel is next to the Menil Collection and The University of St. Thomas in Houston, Texas. It's a small, windowless building with a modern, geometric design. The Chapel, the Menil Collection, and the nearby Cy Twombly gallery were funded by Texas oil millionaires John and Dominique de Menil.

In 1964, Rothko moved into his last New York studio. He set it up with pulleys to move large canvas walls. This helped him control the light from a central skylight, to match the lighting he planned for the Rothko Chapel. Even with warnings about the different light in New York and Texas, Rothko continued his experiment. He began working on the canvases. Rothko told friends he wanted the chapel to be his most important artistic statement. He was very involved in the building's design, insisting on a central skylight like his studio. Architect Philip Johnson couldn't agree with Rothko's ideas about the light. He left the project in 1967 and was replaced by Howard Barnstone and Eugene Aubry. The architects often flew to New York to talk with Rothko. Once, they brought a small model of the building for his approval.

For Rothko, the chapel was meant to be a special place, a pilgrimage site far from the art centers like New York. It was for people seeking Rothko's new "religious" art. At first, the chapel was planned to be Roman Catholic. For the first three years (1964–67), Rothko thought it would stay that way. So, his design for the building and the religious meaning of the paintings were inspired by Catholic art and architecture. Its eight-sided shape is based on a Byzantine church. The three-panel format of the paintings is based on Crucifixion artworks. The de Menils believed the universal "spiritual" side of Rothko's work would fit well with Catholic elements.

Rothko's painting technique needed a lot of physical strength, which the ailing artist no longer had. To create the paintings he imagined, Rothko had to hire two assistants. They applied the chestnut-brown paint in quick strokes, layer after layer, using "brick reds, deep reds, black mauves." For half of the works, Rothko didn't apply any paint himself. He was mostly happy to supervise the slow, hard process. He felt finishing the paintings was "torment." He said the result was "something you don't want to look at."

The chapel is the result of six years of Rothko's life. It shows his growing interest in spiritual ideas. For some, seeing these paintings is a spiritual experience. It makes one think about the limits of experience and one's own existence. For others, the chapel holds fourteen large paintings with dark, almost solid surfaces. These paintings represent deep thought and mystery.

The chapel paintings include a set of three brown panels on the central wall. Each panel is 5 by 15 feet. There are also two sets of three black rectangular paintings on the left and right walls. Between these sets are four individual paintings, each 11 by 15 feet. One more individual painting faces the central set from the opposite wall. This arrangement surrounds the viewer with large, powerful dark images. Even though they are based on religious symbols (like the three-panel format) and hints of the crucifixion, the paintings are hard to connect directly to traditional Christian ideas. They might affect viewers in a subtle way. They can make viewers think deeply about spiritual or artistic questions, like a religious symbol with specific meaning. In this way, Rothko's removal of clear symbols both removes and creates barriers to understanding the art.

These works would be his final artistic message to the world. They were finally shown at the chapel's opening in 1971. Rothko never saw the finished chapel and never installed the paintings himself. At the dedication on February 28, 1971, Dominique de Menil said, "We are cluttered with images and only abstract art can bring us to the threshold of the divine." She noted Rothko's bravery in painting what some called "impenetrable fortresses" of color. For many critics, the drama of Rothko's work is how the paintings exist between "nothingness or emptiness" and "dignified 'mute icons' offering 'the only kind of beauty we find acceptable today.'"

Rothko's Legacy

Art historian David Anfam has listed all of Rothko's 836 paintings on canvas in his book Mark Rothko: The Works on Canvas: Catalogue Raisonné (1998).

A book by Rothko, The Artist's Reality (2004), was published after his death. It's about his ideas on art and was edited by his son, Christopher.

Red, a play by John Logan about Rothko's life, opened in London in 2009. The play, starring Alfred Molina, focused on the time of the Seagram Murals. It received great reviews and was very popular. In 2010, Red opened on Broadway and won six Tony Awards, including Best Play. Molina played Rothko in both London and New York.

In Rothko's birthplace, Daugavpils, Latvia, a monument to him was unveiled in 2003. In 2013, the Mark Rothko Art Centre opened in Daugavpils. Rothko's family donated a small collection of his original works to the center.

Many of Rothko's works are held by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, both in Madrid. The Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Art Collection in Albany, NY, includes Rothko's late painting, Untitled (1967).

Bill Clinton and Hillary Rodham Clinton's first date was to a Rothko exhibit at the Yale University Art Gallery in 1970.

Fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy showed fabrics inspired by Rothko in 1971.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Mark Rothko para niños

In Spanish: Mark Rothko para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |