Women artists facts for kids

For a long time, the history of Western art didn't include many women. Since the 1970s, people have started looking into why this happened. A famous essay from 1971, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" by Linda Nochlin, explored the social rules and barriers that stopped women from becoming artists throughout history. This essay helped start the Feminist art movement.

Even though women have always made art, their work was often hidden, ignored, or not valued as much as men's art. The traditional art world often preferred men's work. Also, some art forms, like textile or fiber arts, were seen as "women's work" and not considered as important.

Women artists faced challenges like not being able to get art education, join professional groups, or show their art in exhibitions. Starting in the late 1960s and 1970s, feminist artists and art historians began to highlight the role of women in the art world. They questioned how art was seen and judged based on gender.

Contents

Art from Ancient Times

We don't know the names of artists from prehistoric times. But studies show that women were often the main artists in Neolithic cultures. They made pottery, textiles, baskets, painted surfaces, and jewellery. Working together on big projects was common. It's thought that Paleolithic cultures were similar. For example, about 75% of the handprints found in Cave paintings from that time belong to women.

Pottery Art

Pottery has a long history in almost all developed cultures. Often, ceramic objects are the only art left from cultures that have disappeared, like the Nok culture in Africa from over 3,000 years ago. Cultures known for their ceramics include the Chinese, Cretan, Greek, Persian, Mayan, Japanese, and Korean cultures. Pottery was invented in different parts of the world, like East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, the Near East, and the Americas. We don't know who these early potters were.

Art from Ancient History

African Art

The geometric Imigongo art comes from Rwanda in East Africa. It's linked to the sacred status of cows, which goes back centuries. This art is made by mixing cow dung with ash and clay, using natural dyes. The colors are bold earth tones. This art is traditionally made by women artists, just like the detailed basket weaving in the area.

Art in India

For about three thousand years, only women in Mithila have been making religious paintings. These paintings show the gods and goddesses of the Hindu religion. This art truly shows an important part of Indian culture.

Classical Europe and the Middle East

Early records from Western cultures rarely name individual artists. However, women are shown in art, and some are seen working as artists. Ancient writers like Homer, Cicero, and Virgil mention women's important roles in making textiles, poetry, music, and other cultural activities.

One of the first European records to name individual artists is by Pliny the Elder. He wrote about several Greek women painters. One was Helena of Egypt, daughter of Timon of Egypt. Some modern experts think the Alexander Mosaic might have been her work, not Philoxenus's. Helena was said to have painted a battle scene that hung in the Temple of Peace in Rome. Other named women artists include Timarete, Eirene, Kalypso, Aristarete, Iaia, and Olympias.

While little of their work survives, a Greek pot called a caputi hydria shows women working alongside men in a workshop, painting vases.

European Art

Medieval Period

-

A scene from the Bayeux Tapestry showing Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, encouraging Duke William's soldiers during the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

-

Herrad of Landsberg, Self portrait from Hortus deliciarum, around 1180.

-

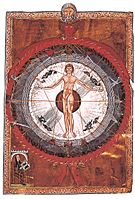

Hildegard of Bingen, "Universal Man" picture from Hildegard's Liber Divinorum Operum, 1165.

-

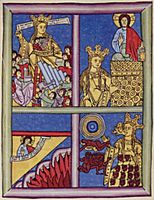

Hildegard von Bingen, Motherhood from the Spirit and the Water, 1165, from Liber divinorum operum, Benediktinerinnenabtei Sankt Hildegard, Eibingen.

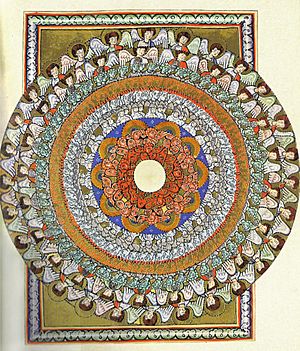

Artists from the Medieval period include Claricia, Diemudus, Ende, Guda, Herrade of Landsberg, and Hildegard of Bingen. In the early Medieval period, women often worked with men. Pictures in old books, embroideries, and carved designs show women working in these arts. Records also show they were brewers, butchers, and wool sellers.

Artists, including women, were usually from a small group of society who didn't have to do hard labor. Women artists were often wealthy noblewomen or nuns. Noblewomen often created embroideries and textiles. Nuns often made beautiful pictures in books (illuminations).

Many embroidery workshops existed in England, especially in Canterbury and Winchester. Opus Anglicanum, or English embroidery, was famous across Europe. A 13th-century church record listed over two hundred pieces. It's believed women did almost all of this work.

The Bayeux Tapestry

One of the most famous embroideries from the Medieval period is the Bayeux Tapestry. It's not a tapestry, but an embroidery made with wool on nine linen panels, and it's 230 feet long! It shows about seventy scenes telling the story of the Battle of Hastings and the Norman Conquest of England. The Bayeux Tapestry might have been made in a workshop, by a noblewoman and her helpers, or in a nunnery.

Sylvette Lemagnen, who takes care of the tapestry, said in 2005:

The Bayeux tapestry is one of the greatest achievements of Norman Romanesque art. It's amazing that it has survived almost completely for nine centuries. Its unusual length, beautiful colors, amazing craftsmanship, and the genius of its creator make it endlessly fascinating.

The High Middle Ages

In the 14th century, a royal workshop was recorded at the Tower of London. Many named artists from the Medieval Period were manuscript illuminators. These include Ende, a 10th-century Spanish nun; Guda, a 12th-century German nun; and Claricia, a 12th-century laywoman in a Bavarian writing studio. These women, and many unnamed illuminators, learned a lot in convents. Convents were the main places for women to learn during this time.

In many parts of Europe, women faced more restrictions in the 11th century. Convents changed too. In the British Isles, convents became less important for learning after the Norman Conquest. They were led by male abbots instead of abbesses. In Pagan Scandinavia (Sweden), the only female runemaster (someone who carves runes), Gunnborga, worked in the 11th century.

In Germany, however, convents kept their role as learning centers. This was partly because convents were often led by unmarried women from royal and noble families. So, the best art by women in the late Medieval period came from Germany. Good examples are the works of Herrade of Landsberg and Hildegard of Bingen.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) was a great German thinker and artist. She wrote many books, hymns, and plays. From a young age, she said she had visions. When the Pope supported her claims, she became a very important intellectual. Her visions became part of her famous work, Scivias (Know the Ways of the Lord), in 1142. This book has thirty-five visions that tell the story of salvation. The pictures in Scivias show Hildegard having visions in her monastery. They are different from other art of that time, with bright colors, strong lines, and simple shapes. Even though Hildegard probably didn't draw them herself, their unique style suggests she guided their creation closely.

The 12th century saw cities, trade, travel, and universities grow in Europe. These changes also affected women's lives. Women could run their husbands' businesses if they became widows. The Wife of Bath in Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales is an example. Women were also allowed to join some artisan guilds. Records show women were very active in textile industries in Flanders and Northern France. Old manuscripts often show women with spindles. In England, women made Opus Anglicanum, which were rich embroideries for church or fancy clothes.

Women also became more active in making illuminated manuscripts. Many women likely worked with their husbands or fathers. By the 13th century, most illuminated manuscripts were made in commercial workshops. By the end of the Middle Ages, women seemed to be the majority of artists and scribes, especially in Paris. However, when printing began, and book illustrations moved to printmaking like woodcuts and engravings, women were less involved. This slowed down their progress as artists.

Meanwhile, Jefimija (1349-1405), a Serbian noblewoman and nun, was known as a poet and a skilled needlewoman and engraver. She carved a sad poem for her dead son on the back of a special two-panel icon. This made the already valuable artwork even more precious.

In 15th-century Venice, the daughter of glass artist Angelo Barovièr was known for a special glass design from Venetian Murano. She was Marietta Barovier, a Venetian glass artist. It took several centuries before women could work with glass art again.

Renaissance Art

-

Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-Portrait, 1554.

-

Esther Inglis, Portrait, 1595.

Artists from the Renaissance era include Sofonisba Anguissola, Lucia Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana, Fede Galizia, Diana Scultori Ghisi, Caterina van Hemessen, Esther Inglis, Barbara Longhi, Maria Ormani, Marietta Robusti (daughter of Tintoretto), Properzia de' Rossi, Levina Teerlinc, Mayken Verhulst, and St. Catherine of Bologna (Caterina dei Vigri).

This was the first time in Western history that many female artists became famous around the world. This happened because of big cultural changes. One change was the rise of humanism, a philosophy that valued the dignity of all people. This helped improve the status of women. Also, the idea of the "individual artist" became more important.

Two important books show this change: On Famous Women and The City of Women. Boccaccio, a 14th-century humanist, wrote De mulieribus claris (On Famous Women) (1335–59), a collection of biographies of women. He included Thamar, an ancient Greek vase painter. In 15th-century copies of On Famous Women, Thamar was shown painting a self-portrait.

Christine de Pizan, a remarkable French writer, wrote Book of the City of Ladies in 1405. This book was about a city where independent women lived free from criticism. She included real women artists, like Anastasia, who was considered one of the best Parisian illuminators.

Other humanist writings led to more education for Italian women. The most famous was Il Cortegiano or The Courtier by Baldassare Castiglione in the 16th century. This popular book said that both men and women should be educated in social arts. His influence made it acceptable for noblewomen to study visual arts, music, and literature.

Sofonisba Anguissola was the most successful noblewoman who benefited from this new education and became a recognized painter. She was a pioneer and role model for future women artists. Artists who were not noblewomen were also affected. For example, Lavinia Fontana and Caterina van Hemessen started painting self-portraits, showing themselves not just as painters but also as musicians and scholars. Fontana benefited from the open-minded attitudes in her city, Bologna, where the university had accepted women scholars since the Middle Ages.

As humanism grew, the focus shifted from craftsmen to artists. Artists were now expected to know about perspective, math, ancient art, and the human body. In the late Renaissance, artist training began to move from workshops to Academies. Women then faced a long struggle to get full access to this training, which wasn't fully resolved until the late 19th century.

Even though many noblewomen had some art training, most chose marriage over an art career. This was true for two of Sofonisba Anguissola's sisters. The women recognized as artists during this time were either nuns or daughters of painters. Most Italian women artists in the 15th century who found success were connected to convents. These included Caterina dei Virgi, Antonia Uccello, and Suor Barbara Ragnoni.

During the 15th and 16th centuries, most women who became successful artists were the children of painters. This was probably because they could get training in their fathers' workshops. Examples include Lavinia Fontana, the miniature portrait painter Levina Teerlinc, and the portrait painter Caterina van Hemessen.

While Italian women artists were somewhat unusual, in parts of Europe like northern France and Flanders, it was more common for children of both genders to follow their father's profession. In the Low Countries, where women had more freedom, many Renaissance artists were women. Records from the Guild of Saint Luke in Bruges show that they accepted women as members. By the 1480s, 25% of their members were women, many likely working as manuscript illuminators.

Nelli's Last Supper

A fragile 22-foot canvas roll found in Florence recently turned out to be an amazing treasure. Thanks to American philanthropist Jane Fortune (who died in 2018) and author Linda Falcone, and their group, Advancing Women Artists Foundation, this roll was saved. After four years of careful restoration by a team led by women, the brilliance of the 16th-century artist, suor Plautilla Nelli, was revealed. She was a self-taught nun and the only Renaissance woman known to have painted the Last Supper. The painting went on display at the Santa Maria Novella Museum in Florence in October 2019. By early 2020, AWA had helped restore 67 works by female artists found in Florentine collections.

Baroque Era Art

-

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, around 1615–17, Curtis Galleries, Minneapolis.

-

Louise Moillon, The Fruit Seller, 1631, Louvre.

-

Giovanna Garzoni, Still Life with Bowl of Citrons, 1640, tempera on vellum, Getty Museum, Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, California.

-

Rachel Ruysch, Still-Life with Bouquet of Flowers and Plums, oil on canvas, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

-

Mary Beale, Self-portrait, around 1675–80.

-

Josefa de Ayala (Josefa de Óbidos), Still-life, around 1679, Santarém, Municipal Library.

Artists from the Baroque era include Mary Beale, Élisabeth Sophie Chéron, Giovanna Garzoni, Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Leyster, Maria Sibylla Merian, Louise Moillon, Josefa de Ayala, Maria van Oosterwijk, Rachel Ruysch, and Elisabetta Sirani. Like in the Renaissance, many women Baroque artists came from artist families. Artemisia Gentileschi was trained by her father, Orazio Gentileschi, and worked with him. Luisa Roldán was trained in her father's sculpture workshop.

Women artists in this period started to change how women were shown in art. Artists like Elisabetta Sirani created images of women as strong, thinking individuals, not just passive figures. A great example is Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Holofernes. In this painting, Judith is shown as a powerful woman taking control of her own destiny. While other artists showed Judith as passive, Gentileschi's Judith is actively involved.

Still life painting became important around 1600, especially in the Netherlands. Women were leaders in this art style. This type of painting was good for women because they could easily get the objects needed for still life. In the North, artists like Clara Peeters painted "breakfast pieces" and luxury goods. Maria van Oosterwijk was a famous flower painter, and Rachel Ruysch painted detailed flower arrangements. In other areas, still life was less common, but important women artists included Giovanna Garzoni, who made realistic vegetable arrangements on parchment, and Louise Moillon, known for her brightly colored fruit still life paintings.

Important Artists of the Era

Judith Leyster was the daughter of weavers and one of nine children. She wasn't born into a traditional art family, but her family supported her dream of becoming a painter. She studied painting between ages 11 and 16. She worked as an apprentice for years before opening her own studio. She became the first woman to join the Harleem Guild. Her work showed strong and lively techniques, which was unusual for many female artists at the time. Her art was seen as powerful, like that of Artemisia Gentileschi. After her death, Leyster's work was forgotten for over two centuries until it was rediscovered.

18th Century Art

-

Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun (1755–1842), Self-portrait, around 1780s.

-

Rosalba Carriera (1675–1757), Self-portrait, 1715.

-

Anne Vallayer-Coster, Attributes of Music, 1770.

-

Angelica Kauffman, Literature and Painting, 1782, Kenwood House.

-

Marie-Gabrielle Capet, Self-portrait, 1783.

-

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Self-portrait with two pupils, Marie-Gabrielle Capet and Marie-Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond 1785, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

Marguerite Gérard, First steps, oil on canvas, around 1788.

Artists from this period include Rosalba Carriera, Maria Cosway, Marguerite Gérard, Angelica Kauffman, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Mary Moser, Ulrika Pasch, Anna Dorothea Therbusch, Anne Vallayer-Coster, and Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun.

In many European countries, art Academies decided what was good art. They also trained artists, showed artwork, and helped sell art. Most Academies were not open to women. For example, in France, the powerful Paris Academy had 450 members between the 17th century and the French Revolution, but only fifteen were women. Most of these were daughters or wives of members. In the late 18th century, the French Academy decided not to admit any women at all.

The most important type of painting then was history painting. These were large paintings with many figures showing historical or mythical events. To create such paintings, artists studied ancient sculptures. Women had limited or no access to this academic training. So, there are no large history paintings by women from this period. Some women became famous in other types of art, like portraiture.

Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun used her portrait skills to create an allegorical scene, Peace Bringing Back Plenty. She called it a history painting to get into the Academy. After her work was shown, she was told she had to attend formal classes or lose her painting license. She became a favorite of the court and a celebrity, painting over forty self-portraits that she sold.

In England, two women, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser, were founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1768. Kauffmann helped Maria Cosway enter the Academy. Even though Cosway became a successful painter of mythological scenes, both women had a difficult position at the Royal Academy. The focus on Academic art was a big barrier for women studying art until the 20th century. This was true for both actual access to classes and how families and society viewed middle-class women becoming artists. Women were not allowed into the Academy's schools until 1861.

By the late 18th century, there were important steps forward for women artists. In Paris, the Salon, an art exhibition, opened to non-Academic painters in 1791. This allowed women to show their work in this important annual exhibition. Also, women were more often accepted as students by famous artists like Jacques-Louis David.

19th Century Art

Painters

Women artists of the early 19th century include Marie-Denise Villers, who painted portraits; Constance Mayer, who painted portraits and allegories; and Marie Ellenrieder, known for her religious paintings.

In the second half of the century, Emma Sandys, Marie Spartali Stillman, and Maria Zambaco were women artists of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Also influenced by them were Evelyn De Morgan and the activist and painter Barbara Bodichon.

Impressionist painters Berthe Morisot, Marie Bracquemond, and the Americans Mary Cassatt and Lucy Bacon, joined the French Impressionist movement of the 1860s and 1870s. American Impressionist Lilla Cabot Perry was influenced by her studies with Monet and by Japanese art. Cecilia Beaux was an American portrait painter who also studied in France. Olga Boznańska is considered one of the best-known Polish women artists, linked to Impressionism.

Rosa Bonheur was the most famous female artist of her time, known worldwide for her animal paintings. Elizabeth Thompson (Lady Butler) became famous for large history paintings, especially military scenes with many horses, like Scotland Forever!.

Kitty Lange Kielland was a Norwegian landscape painter.

Elizabeth Jane Gardner was an American academic painter. She was the first American woman to show her art at the Paris Salon. In 1872, she became the first woman to win a gold medal at the Salon.

In 1894, Suzanne Valadon was the first woman admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in France. Anna Boch was a post-impressionist painter, as was Laura Muntz Lyall.

-

Mary Cassatt, Tea, 1880, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

-

Maria Bashkirtseva, In the Studio, 1881, oil on canvas, Dnipro State Art Museum.

-

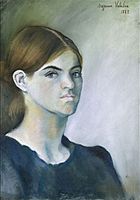

Suzanne Valadon, Self-portrait, 1883.

-

Berthe Morisot, L'Enfant au Tablier Rouge, 1886, American Art Museum.

-

Anna Bilińska-Bohdanowicz, A Negress, 1884, Warsaw National Museum.

-

Olga Boznańska, Girl with Chrysanthemums, 1894, National Museum, Kraków.

-

Rosa Bonheur, The Horse Fair, 1853–1855, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

Elizabeth Thompson, Remnants of an Army, 1879, Tate. She specialized in military scenes.

Sculpture

Before the 19th century, an amazing businesswoman named Eleanor Coade (1733 – 1821) emerged in Georgian England. She discovered her own artistic talent later in life. She became known for making Neoclassical statues, building decorations, and garden ornaments. These were made of Lithodipyra or Coade stone for over 50 years, from 1769 until her death. Lithodipyra ("stone fired twice") was a high-quality, strong, weather-resistant ceramic stoneware. Statues made from this ceramic still look almost new today. Coade didn't invent "artificial stone," but she likely perfected the clay recipe and the firing process. She combined excellent manufacturing and artistic taste with business skills to create very successful stone products.

Eleanor Coade developed her talent as a sculptor. She showed about 30 sculptures with classical themes at the Society of Artists between 1773 and 1780. After her death, her Coade stoneware was used for renovations at Buckingham Palace. It was also used by famous sculptors in their large works, like William Frederick Woodington's South Bank Lion (1837) on Westminster Bridge, London.

The century also produced women sculptors in the East, like Seiyodo Bunshojo (1764-1838), a Japanese netsuke carver and Haiku writer. In the West, there were Julie Charpentier, Elisabet Ney, Helene Bertaux, Camille Claudel, and Edmonia Lewis. Lewis, an African-Ojibwe-Haitian American artist, began her art studies at Oberlin College. Her sculpting career started in 1863. She opened a studio in Rome, Italy and showed her marble sculptures in Europe and the United States.

Photography

Constance Fox Talbot might be the first woman to ever take a photograph. Later, Julia Margaret Cameron and Gertrude Kasebier became well known in the new field of photography. There were no old rules or established training to hold them back. Sophia Hoare, another British photographer, worked in Tahiti and other parts of Oceania.

In France, the birthplace of photography, there was Geneviève Élisabeth Disdéri (around 1817–1878). In 1843, she married the pioneering photographer André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri. She worked with him in their studio in Brest from the late 1840s. After her husband moved to Paris in 1852, Geneviève continued to run the studio alone. She is remembered for her 28 views of Brest, mostly buildings, published in 1856. She was one of the first professional female photographers in the world.

Female Education in the 19th Century

During this century, women in Europe and North America gained more access to art schools and formal training. The British Government School of Design, later the Royal College of Art, admitted women from its start in 1837. However, they had a "Female School" that was treated differently. For example, "life" classes for women involved drawing a man wearing a suit of armor for several years.

The Royal Academy Schools finally admitted women in 1861, but students initially only drew draped models. Other schools in London, like the Slade School of Art from the 1870s, were more open. The Society of Female Artists (now called The Society of Women Artists) was founded in 1855 in London. It has held annual exhibitions since 1857. One woman who succeeded without higher art education was the natural scientist, writer, and illustrator, Beatrix Potter (1866-1943).

English Women Painters Who Exhibited at the Royal Academy of Art (Early 19th Century)

- Sophie Gengembre Anderson

- Mary Baker

- Ann Charlotte Bartholomew

- Maria Bell

- Barbara Bodichon

- Joanna Mary Boyce

- Margaret Sarah Carpenter

- Fanny Corbaux

- Rosa Corder

- Mary Ellen Edwards

- Harriet Gouldsmith

- Mary Harrison

- Jane Benham Hay

- Anna Mary Howitt

- Mary Moser

- Martha Darley Mutrie

- Ann Mary Newton

- Emily Mary Osborn

- Kate Perugini

- Louise Rayner

- Ellen Sharples

- Rolinda Sharples

- Rebecca Solomon

- Elizabeth Emma Soyer

- Isabelle de Steiger

- Henrietta Ward

20th Century Art

-

Hilma af Klint, Svanen (The Swan), No. 17, Group IX, Series SUW, October 1914 – March 1915. This abstract work was never shown during af Klint's lifetime.

-

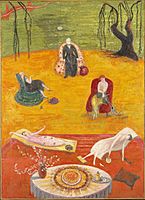

Florine Stettheimer, Heat, around 1919, Brooklyn Museum.

-

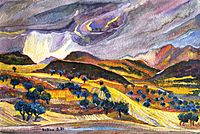

Georgia O'Keeffe, Blue and Green Music, 1921, oil on canvas.

-

Aleksandra Ekster, Costume design for Romeo and Juliette, 1921, M.T. Abraham Foundation.

-

Gwen John, The Convalescent (around 1923–24), one of ten versions of this composition.

-

Barbara Hepworth,Sphere with Inner Form, 1963, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands.

-

Alina Szapocznikow, Grands Ventres, 1968, Kröller-Müller Museum.

-

Louise Bourgeois, Maman against the Thames, London.

Notable women artists from this period include: Elene Akhvlediani, Hannelore Baron, Vanessa Bell, Lee Bontecou, Louise Bourgeois, Romaine Brooks, Emily Carr, Leonora Carrington, Mary Cassatt, Elizabeth Catlett, Camille Claudel, Sonia Delaunay, Marthe Donas, Joan Eardley, Marisol Escobar, Dulah Marie Evans, Audrey Flack, Mary Frank, Helen Frankenthaler, Elisabeth Frink, Wilhelmina Weber Furlong, Françoise Gilot, Natalia Goncharova, Nancy Graves, Grace Hartigan, Barbara Hepworth, Eva Hesse, Sigrid Hjertén, Hannah Höch, Frances Hodgkins, Malvina Hoffman, Irma Hünerfauth, Margaret Ponce Israel, Gwen John, Elaine de Kooning, Käthe Kollwitz, Lee Krasner, Frida Kahlo, Hilma af Klint, Laura Knight, Barbara Kruger, Marie Laurencin, Tamara de Lempicka, Séraphine Louis, Dora Maar, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, Maruja Mallo, Agnes Martin, Ana Mendieta, Joan Mitchell, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Gabriele Münter, Alice Neel, Louise Nevelson, Georgia O'Keeffe, Betty Parsons, Aniela Pawlikowska, Orovida Camille Pissarro, Irene Rice Pereira, Paula Rego, Bridget Riley, Verónica Ruiz de Velasco, Anne Ryan, Charlotte Salomon, Augusta Savage, Zofia Stryjeńska, Zinaida Serebriakova, Sarai Sherman, Henrietta Shore, Sr. Maria Stanisia, Marjorie Strider, Carrie Sweetser, Annie Louisa Swynnerton, Franciszka Themerson, Suzanne Valadon, Remedios Varo, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Nellie Walker, Marianne von Werefkin and Ogura Yuki.

Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) was a pioneer of abstract painting. She worked long before her male peers in abstract art. She was Swedish and often showed her realistic paintings. But her abstract works were not shown until 20 years after her death, as she requested. She saw herself as a spiritual and mystic artist.

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1865–1933) was a Scottish artist. Her works helped define the "Glasgow Style" of the 1890s and early 20th century. She often worked with her husband, Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Their art influenced Europe. She exhibited with Mackintosh at the 1900 Vienna Secession. Her work is thought to have influenced artists like Gustav Klimt.

Annie Louisa Swynnerton (1844-1933) was a portrait, landscape, and 'symbolist' artist. Other artists like John Singer Sargent thought she was one of the best and most creative artists of her time. However, she was not allowed into mainstream art schools. She moved abroad to study and spent much of her life in France and Rome. These places had more liberal attitudes, allowing her to explore many subjects. She was not officially recognized in Britain until 1923, at age 76. She became the first woman admitted to the Royal Academy of Arts.

Wilhelmina Weber Furlong (1878–1962) was an early American modernist in New York City. She made important contributions to modern American art. Aleksandra Ekster and Lyubov Popova were Constructivist, Cubo-Futurist, and Suprematist artists. They were well known in Kiev, Moscow, and Paris in the early 20th century. Other important women artists in the Russian avant-garde included Natalia Goncharova and Varvara Stepanova. Sonia Delaunay and her husband founded Orphism.

In the Art Deco era, Hildreth Meière made large mosaics. She was the first woman to receive the Fine Arts Medal from the American Institute of Architects. Tamara de Lempicka, also from this era, was an Art Deco painter from Poland. Sr. Maria Stanisia became a notable portrait painter, mainly of religious figures. Georgia O'Keeffe was born in the late 19th century. She became known for her paintings of flowers, bones, and landscapes of New Mexico.

Surrealism, an important art style in the 1920s and 1930s, had many prominent women artists. These included Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage, Dorothea Tanning, and Remedios Varo. There were also unique artists like the British self-taught, often funny, observer, Beryl Cook (1926-2008).

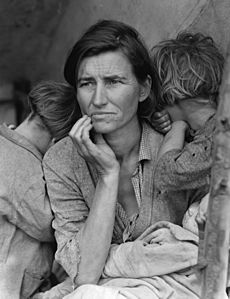

Women Photographers

Lee Miller rediscovered solarization and became a high fashion photographer. Dorothea Lange documented the Great Depression. Berenice Abbott created images of famous buildings and celebrities. Margaret Bourke-White created industrial photographs that were featured on the cover of the first Life Magazine. Diane Arbus based her photography on people outside mainstream society. Graciela Iturbide's works dealt with Mexican life and feminism. Tina Modotti produced "revolutionary icons" from Mexico in the 1920s. Annie Leibovitz's photographs were of rock and roll and other celebrity figures. Other women who broke barriers include Eve Arnold, Marilyn Silverstone, and Inge Morath of Magnum.

Theatrical Designers

Women graphic artists and illustrators, like the rare female cartoonist, Claire Bretécher, have contributed greatly to their field. On a larger scale, the following theatrical designers have been notable: Elizabeth Polunin, Doris Zinkeisen, Adele Änggård, Kathleen Ankers, Madeleine Arbour, Marta Becket, Maria Björnson, Madeleine Boyd, Gladys Calthrop, Marie Anne Chiment, Millia Davenport, Kirsten Dehlholm, Victorina Durán, Lauren Elder, Heidi Ettinger, Soutra Gilmour, Rachel Hauck, Marjorie B. Kellogg, Adrianne Lobel, Anna Louizos, Elaine J. McCarthy, Elizabeth Montgomery, Armande Oswald, Natacha Rambova, Kia Steave-Dickerson, Karen TenEyck, Donyale Werle.

Multi-Media Art

Mary Carroll Nelson founded the Society of Layerists in Multi-Media (SLMM). In the 1970s, Judy Chicago created The Dinner Party, a very important work of feminist art. Helen Frankenthaler was an Abstract Expressionist painter. Lee Krasner was also an Abstract Expressionist artist. Elaine de Kooning was an abstract figurative painter. Anne Ryan was a collagist. Jane Frank worked with mixed media on canvas. In Canada, Marcelle Ferron was a leader in automatism.

From the 1960s onwards, feminism led to a great increase in interest in women artists and their academic study. Important contributions have been made by art historians like Germaine Greer and Linda Nochlin. Figures like Artemisia Gentileschi and Frida Kahlo became feminist icons. The Guerilla Girls, an anonymous group of women formed in 1985, spoke out about unfairness for gender and race in the art world. They made many posters to raise awareness and create change.

In 1996, Catherine de Zegher organized an exhibition of 37 great women artists from the 20th century. The exhibition, Inside the Visible, traveled to several museums. It included works from the 1930s through the 1990s by artists like Claude Cahun, Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Nancy Spero, Charlotte Salomon, and Magdalena Abakanowicz.

Textile Art

Women's textiles were often seen as just for the home, not as real art. Art was expected to show "artist-genius," which was linked to men. Because textiles were seen as functional, they weren't considered art. This led women to avoid techniques linked to femininity, like delicate lines or "feminine" colors. They didn't want to be called feminine artists.

However, in recent years, this idea has been challenged. Textiles are now used to create art that shows female experiences and struggles. Some feminists use embroidery to make feminist statements. They challenge the idea that textiles should only be linked to home life and femininity. Challenging art practices that exclude women shows the politics and gender bias in traditional art. It helps break down class and male-dominated divisions. These traditional female art forms are now used to empower women. They help develop knowledge and reclaim traditional women's skills that society had undervalued.

Also see Craftivism.

Ceramic Art

The creation of ceramic art objects became popular again in the late 19th century in Japan and Europe. This is known as Studio pottery. It includes sculpture and tesserae, which are mosaic cubes that go back to ancient Persia. Several things helped studio pottery emerge: art pottery, the Arts and Crafts movement, the Bauhaus, and the rediscovery of traditional pottery.

Leading trends in British studio pottery in the 20th century were shaped by both men and women. These include Bernard Leach, Dora Billington, Lucie Rie, and Hans Coper. Leach (1887–1979) created a pottery style influenced by Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and medieval English forms. This style was very popular in British studio pottery in the mid-20th century. Leach's influence spread through his book A Potter's Book and his apprentice system.

Other ceramic artists influenced the field through their positions in art schools. Dora Billington (1890–1968) studied art and worked in the pottery industry. She became head of pottery at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. She worked with materials Leach did not, like tin-glazed earthenware.

Since the 1960s, a new generation of potters began to experiment with abstract ceramic objects. They explored different surfaces and glazes. These artists include Alison Britton, Ruth Duckworth, and Elizabeth Fritsch. Elizabeth Fritsch's work is in major collections and museums worldwide. Also, the reputation of British ceramicists has attracted talent from around the world. These include Indian Nirmala Patwardhan, Kenyan Magdalene Odundo, and Iranian Homa Vafaie Farley.

In the United States, pottery was important to the Arts and Crafts movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some potters in the U.S. adopted ideas from studio pottery movements in Britain and Japan. Artists from around the world who came to the United States helped people appreciate ceramics as art. These included Marguerite Wildenhain, Maija Grotell, Susi Singer, and Gertrude and Otto Natzler. Important studio potters in the United States include Otto and Vivika Heino, Beatrice Wood, and Amber Aguirre.

Meanwhile, in the African Great Lakes region, the Batwa people still follow their ancient way of life. They are among the most marginalized people in the world. Their women (and sometimes men) continue the centuries-old custom of making pottery. This pottery has been used to trade with farmers and herders in the region. Their pots range from plain to highly decorated.

-

Vase thrown by Lucie Rie.

-

Ceramic bird by Margaret Hine, 1950s. Glazed stoneware with sgraffito decoration.

Contemporary Artists

In 1993, Rachel Whiteread was the first woman to win the Tate Gallery's Turner Prize. Gillian Wearing won the prize in 1997, when all the nominees were women. In 1999, Tracey Emin got a lot of media attention for her entry My Bed, but she didn't win. In 2006, the prize went to abstract painter, Tomma Abts.

In 2001, a conference called "Women Artists at the Millennium" was held at Princeton University. A book with the same name was published in 2006. It featured major art historians analyzing prominent women artists like Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Rachel Whiteread, and Rosemarie Trockel.

Internationally famous contemporary artists who are women also include Magdalena Abakanowicz, Marina Abramović, Yayoi Kusama, Jenny Holzer, Cindy Sherman, Shazia Sikander, Lorna Simpson, and Kara Walker.

Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama's paintings, collages, sculptures, performance art, and installations all show an obsession with repetition and patterns. Her work has elements of feminism, minimalism, surrealism, pop art, and abstract expressionism. It also includes personal and psychological themes. In November 2008, her 1959 painting No. 2 sold for $5,100,000. This was a record price for a work by a living female artist at that time.

From 2010–2011, the Pompidou Centre in Paris showed works by major contemporary women artists from its own collection. In 2010, Eileen Cooper was elected the first woman "Keeper of the Royal Academy." In 1995, Dame Elizabeth Blackadder became "Her Majesty's painter and limber in Scotland."

Another type of women's art is environmental art. As of December 2013, the Women Environmental Artists Directory listed 307 women environmental artists. These include Marina DeBris, who uses beach trash to raise awareness about ocean pollution. Vernita Nemec recently used junk mail to show how complex modern life is. Betty Beaumont is seen as a pioneer of environmental art. She uses art to challenge our beliefs and actions.

-

Kenojuak Ashevak Window of John Bell Chapel, 2004, Appleby College, Oakville, Canada.

-

Rachel Whiteread, Holocaust Monument, 2000, Judenplatz, Vienna.

-

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Nierozpoznani ("The Unrecognised Ones"), 2002, in the Cytadela.

-

Hambling's Scallop 2003, tribute to Benjamin Britten, north end of Aldeburgh beach, England.

-

Yayoi Kusama, Ascension of Polkadots on the Trees at the Singapore Biennale, 2006.

-

Shirazeh Houshiary, East window St Martin-in-the-Fields, London.

-

Marina Abramović performing in The Artist is Present at the Museum of Modern Art, May 2010.

Why Women Artists Were Overlooked

Women artists have often been misunderstood or misrepresented in history. This was sometimes on purpose, and sometimes not. These misrepresentations were often due to the social rules of the time and the fact that men mostly controlled the art world. Here are some reasons why:

- Missing Information: There isn't much information about the lives of many women artists.

- No Signatures: Women artists often worked in art forms that were not usually signed. In the Early Medieval period, both monks and nuns created illuminated manuscripts, but they rarely signed their work.

- Art Guilds: In the Medieval and Renaissance periods, many women worked in art workshops. They worked under a male head, often their father. Until the 12th century, there are no records of workshops led by women. Guild rules often stopped women from becoming masters, so they remained "unofficial."

- Naming Changes: The custom of women taking their husbands' last names makes it hard to research female artists. Especially when a work is only signed with a first initial and last name. For example, Jane Frank was born Jane Schenthal. Jane "Frank" didn't exist until she married. This creates a break in the artist's identity.

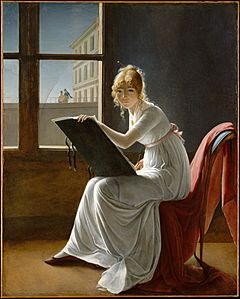

- Wrong Identity and Attribution: In the 18th and 19th centuries, art by women was often given to male artists. Some dishonest dealers even changed signatures. For example, some paintings by Judith Leyster were wrongly given to Frans Hals. Marie-Denise Villers' famous painting, Young Woman Drawing (1801), was once thought to be by Jacques-Louis David.

Another reason why female artists were not accepted was that their skills might be different from men's. This was because of their experiences and situations. This difference in art was sometimes feared.

Even with these problems, there's a deeper issue that limited the number of female artists. There are no female artists compared to the fame of Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo. This isn't because women lacked skill. It's because of the oppression and discouragement they faced. The problem lies in the lack of education and opportunities given to women. It's amazing that women managed to achieve artistic skills despite the male-dominated art world.

Women in Outsider Art

The idea of outsider art came about in the 20th century. Mainstream artists, collectors, and critics started to look at art made by people without formal training. This includes self-taught artists, children, folk artists, and people in mental institutions. Some of the first to study this art were the Blaue Reiter group in Germany, and later the French artist Jean Dubuffet. Some noted women considered "art brut" (the French term for outsider art) are:

- Holly Farrell, a 21st-century Canadian self-taught artist known for her Barbie & Ken series.

- Madge Gill (1882–1961), an English artist who made thousands of drawings "guided" by a spirit.

- Annie Hooper (1897–1986), a sculptor of religious art who created nearly 5,000 sculptures.

- Georgiana Houghton (1814–1884), a British spiritualist known for her abstract "spirit drawings."

- Mollie Jenson (1890–1973), who created large concrete sculptures with mosaics.

- Susan Te Kahurangi King (born 1951), a New Zealand artist with autism who creates extraordinary drawings.

- Halina Korn (1902-1978), a Polish artist who started sculpting and painting later in life.

- Maud Lewis (1903–1970), a Canadian folk artist who painted bright scenes on found objects.

- Helen Martins (1897–1976), who transformed her house into a fantastic environment with sculptures.

- Grandma Moses (1860–1961), widely considered a folk artist.

- Judith Scott (1943–2005), an artist with Down syndrome who became an internationally famous fiber artist.

- Anna Zemánková (1908–1986), a self-taught Czech painter whose work was shown at the Venice Biennale.

See also

In Spanish: Mujeres artistas para niños

In Spanish: Mujeres artistas para niños

- Advancing Women Artists Foundation

- Women in Animation

- Lists of women artists

- List of 20th-century women artists

- List of 21st-century women artists

- List of female sculptors

- Australian feminist art timeline

- Beaver Hall Group

- Bonn Women's Museum

- Female comics creators

- Guerrilla Girls On Tour

- National Museum of Women in the Arts

- Native American women in the arts

- Women Environmental Artists Directory

- Women in photography

- Women's International Art Club

- Women surrealists

- Women's Studio Workshop

- The Story of Women and Art, 2014 television documentary

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |