Julia Margaret Cameron facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Julia Margaret Cameron

|

|

|---|---|

Cameron in 1870

|

|

| Born |

Julia Margaret Pattle

11 June 1815 |

| Died | 26 January 1879 (aged 63) Kalutara, British Ceylon

|

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Photography |

| Spouse(s) |

Charles Hay Cameron

(m. 1838) |

Julia Margaret Cameron (born Pattle; 11 June 1815 – 26 January 1879) was a British photographer. She is known as one of the most important portrait photographers of the 1800s.

She took close-up photos of famous people from the Victorian era. She also created pictures that looked like scenes from myths, Christian stories, and books. Her portraits of men, women, and children were very touching.

Julia Margaret Cameron became a photographer later in life, at age 48. Her daughter gave her a camera as a Christmas gift. She quickly took many photos, showing the talent, beauty, and innocence of people who visited her studio. She also made unique story-like pictures. These were inspired by living scenes (like tableau vivant), theatre, and old Italian paintings.

Her photography career was short but busy. She made about 900 photographs over 12 years.

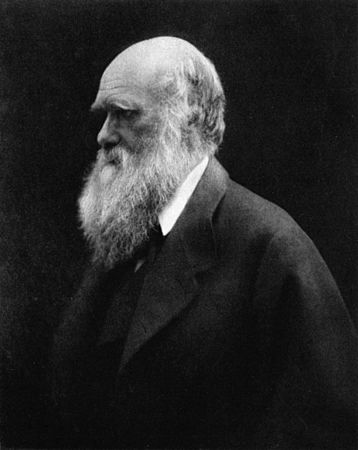

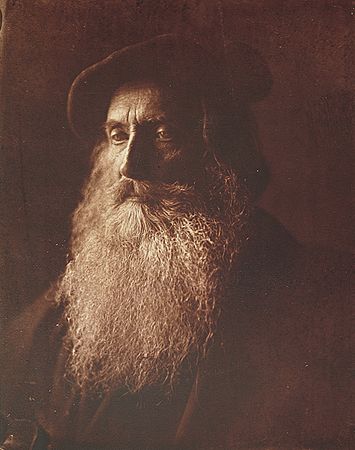

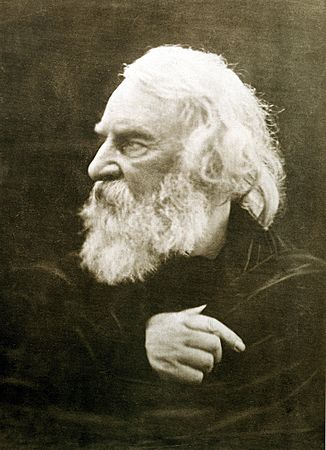

Cameron's work was debated during her time. Some critics thought her soft-focus photos looked unfinished or amateur. However, her portraits of respected men like Charles Darwin and Sir John Herschel were always praised. Her photos have been called "extraordinarily powerful" and "wholly original." She is also known for creating some of the first close-up photos in history.

Contents

Julia Cameron's Early Life

Julia Margaret Cameron was born Julia Margaret Pattle on 11 June 1815. This was in Calcutta, India. Her parents were Adeline Marie and James Peter Pattle.

Her father, James Pattle, was a successful official from England. He worked in India for the East India Company. Her mother was a French aristocrat.

Julia was the fourth of her parents' children. She and six of her sisters grew up to be adults. The seven sisters were known for being charming, witty, and beautiful. They were also close, outspoken, and had their own style. They often wore Indian silks instead of typical Victorian clothes.

All the sisters were sent to France for school. Julia lived there with her grandmother from 1818 to 1834. Then she returned to India.

Marriage and Social Life

Life in South Africa and India

In 1835, Julia visited the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. She went there with her parents to get better after being sick. Many Europeans living in India visited South Africa to recover from illnesses.

While there, she met Sir John Herschel, a British astronomer. She also met Charles Hay Cameron. He was 20 years older than her. Charles was a reformer of Indian law and education. He later invested in coffee farms in what is now Sri Lanka.

Julia and Charles married in Calcutta on 1 February 1838. They had their first child in December of that year. Sir John Herschel was the godfather. Between 1839 and 1852, they had six children. One of them was adopted. In total, the Camerons raised 11 children. Five were their own, five were orphaned relatives, and one was an Irish girl they adopted. Their son, Henry Herschel Hay Cameron, also became a photographer.

In the early 1840s, Julia became a well-known hostess in Anglo-Indian society. She organized social events for the Governor-General, Lord Hardinge. During this time, she also wrote to Herschel about new photography ideas. In 1839, Herschel told her about the invention of photography. In 1842, he sent her some early photographs. These were the first she had ever seen.

Moving to England

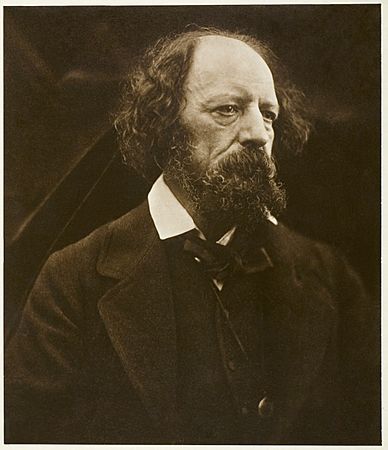

The Camerons moved to England in 1845. They wanted to be closer to their children. In England, they joined London's art and culture scene. Julia often visited Little Holland House in Kensington, London. Her sister, Sara Prinsep, ran a popular meeting place there. It was for Pre-Raphaelite painters, poets, and other artists. Here, Julia met many people she would later photograph, like Alfred Tennyson.

In 1847, Julia was writing poetry and a novel. She also published a translation of a German poem.

In 1848, Charles Cameron fully retired. He invested in coffee and rubber farms in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). The Camerons settled in England. They lived first in Tunbridge Wells, then in East Sheen. Julia joined a society for art education. A painter named George Frederic Watts began a painting of her.

In 1860, Julia visited Alfred Tennyson in Freshwater, a village on the Isle of Wight. She quickly bought a property next door to him. The family moved there and named it "Dimbola." A private gate connected their homes. The two families often hosted famous people. They had music, poetry readings, and plays. This created a lively art scene, similar to Little Holland House. She lived there until 1875.

Julia Cameron's Photography Career

Starting Out as a Photographer

Cameron became very interested in photography in the late 1850s. She may have tried taking photos in the early 1860s. Around 1863, her daughter and son-in-law gave her a camera for Christmas. This gift was meant to keep her busy while her husband was in Ceylon. Her daughter said, "It may amuse you, Mother, to try to photograph during your solitude at Freshwater."

After getting the camera, she turned a chicken coop into her photography studio.

On 29 January 1864, she photographed nine-year-old Annie Philpot. She called this image her "first success." That same year, she made albums of her photos for Watts and Herschel. She also registered her work and got it ready for shows and sales. She was elected to the Photographic Society of London. She stayed a member until she died and showed her work at their yearly exhibitions.

Julia Cameron saw herself as an artist. She did not take photos for money or open a commercial studio. However, she treated her photography like a professional job. She copyrighted, published, and sold her work. Her family's coffee farms in Ceylon were not making much money. So, Cameron may have wanted to earn some income with her photography. Her many portraits of famous people also suggest she hoped to sell them.

Her Work Grows

In 1865, she joined the Photographic Society of Scotland. She also arranged for her photos to be sold through dealers in London. She gave a series of photos called The Fruits of the Spirit to the British Museum. She had her first solo exhibition in November 1865. Her photos were in high demand. She showed her work across Europe, winning awards in Berlin in 1865 and 1866.

Her husband supported her photography. Cameron wrote that he "watched every picture with delight." She said she would run to him with every new photo and listen to his "enthusiastic applause."

In August 1865, the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) bought 80 of her photographs. Three years later, the museum gave her two rooms to use as a studio. This made her the museum's first artist-in-residence.

She took photos of Thomas Carlyle and John Herschel in 1867. By 1868, she was selling photos through two agents in London. In 1869, she created The Kiss of Peace. She thought this was her best work.

In the early 1870s, Cameron's work became even better. Her detailed story-like pictures, with religious, literary, and classical figures, reached their peak. This was with a series of images for Tennyson's Idylls of the King. These were published in 1874 and 1875. During this time, she also wrote Annals of my Glass House. This was an unfinished memoir about her photography career.

Later Life and Legacy

In October 1873, her daughter died during childbirth. Two years later, Cameron and her husband moved to Ceylon. This was because her husband was ill. Also, living costs were lower there. They wanted to be closer to their sons, who managed the family coffee farms. These farms had been damaged by a fungus.

This move largely ended Cameron's photography career. She took few photos afterward. Most were of Tamil servants and workers. Fewer than 30 photos from this time still exist. It was hard to work with her photographic chemicals in the hot, insect-filled climate. Also, fresh water for washing prints was less available.

After a short visit to England, Cameron became very ill. She died on 26 January 1879 in Ceylon. It is often said her last word was "Beauty" or "Beautiful."

In her 12-year career, Cameron made about 900 photographs.

Julia Cameron's Photographic Work

What Influenced Her Art

Julia Cameron was a well-educated and cultured woman. She knew a lot about medieval art, the Renaissance, and the Pre-Raphaelites. She may also have been interested in phrenology. This was a study of how a person's face and body might show their character. Old Master painters also influenced her work. Her photo compositions and use of light are like those of Raphael, Rembrandt, and Titian.

John Herschel, who told Cameron about the invention of photography, was a key influence. He taught her about techniques. Cameron wrote to him, "You were my first teacher and to you I owe all the first experience and insights."

David Wilkie Wynfield was perhaps the most important photographer to influence Cameron. She learned her close-up portrait style from him. She later wrote that she consulted him when she had difficulties. Wynfield also published an album of soft-focus portraits. These showed friends dressed as historical or literary figures. The press compared their work, noting how similar their styles were. She felt his "beautiful photography" inspired all her attempts and successes.

Capturing Genius and Beauty

Cameron's portraits show her closeness to the people she photographed. But she also wanted to capture special qualities. She aimed to show "genius in men and beauty in women." She believed these qualities were signs of something grand and sacred. Her ideas of beauty came from many sources. These included the Bible, classical myths, Shakespeare's plays, and Tennyson's poems.

Cameron herself said she wanted to capture beauty. She wrote, "I longed to arrest all the beauty that came before me and at length the longing has been satisfied." She also wanted to "ennoble Photography" and make it "High Art." She aimed to combine real life with ideal beauty.

She usually chose women for their beauty. She especially liked the "long-necked, long-haired, immature beauty" often seen in Pre-Raphaelite paintings.

Types of Portraits

Cameron's photos are usually put into three groups. These are: important portraits of men, delicate portraits of women, and story-like pictures based on religious and literary works.

Portraits of Men

Cameron's portraits of men were a way of admiring heroes. She wrote to Thomas Carlyle, "When I have had such men before my camera my whole soul has endeavoured to do its duty towards them." She wanted to show their inner greatness as well as their outer looks. She felt the photo was "almost the embodiment of a prayer."

Most of these men were famous scientists, writers, or religious leaders of the Victorian era. Cameron looked to Old Master paintings for ideas. She wanted to capture the greatness she saw in these important men. Her goal was to record this greatness. This led to powerful images that showed her skill with light and shadow. These photos created "the finest and most revealing gallery of eminent Victorians in existence."

One writer, Janet Malcolm, noted how Cameron used hair in her portraits. She wrote that Cameron's close-ups of Tennyson, Darwin, and others were "as much celebrations of beards as of Victorian eminence."

Portraits of Women

Her photos of women are much softer than those of men. They use less dramatic lighting. The camera is usually a more typical distance from the person. These photos are less strong and more traditional than her pictures of men.

Cameron almost always photographed younger women. She never took a picture of her neighbor and friend, Emily Tennyson. A writer about Charles Darwin said Cameron refused to photograph Darwin's wife. She said "no woman must be photographed between the ages of eighteen and seventy."

Her mature photos of women show female identity in a subtle way. They often hide a woman's individual traits. They show identity as changing and having many sides. She often showed women "in pairs, or reflected in a mirror." This often showed "deep ambiguity and anxiety."

Janet Malcolm also noted Cameron's focus on women's hair. She wrote that "the bigger girls were made to undo their buns and chignons." This made their hair "poetically stream or flow or twist around their faces."

-

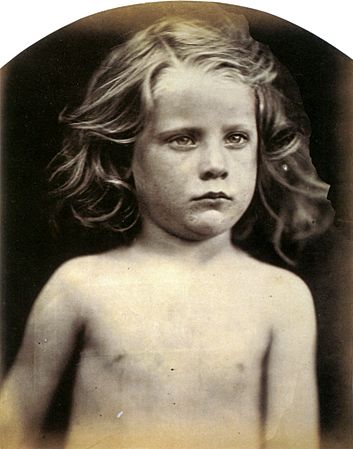

Ellen Terry 1864

-

Alice Liddell, 1872

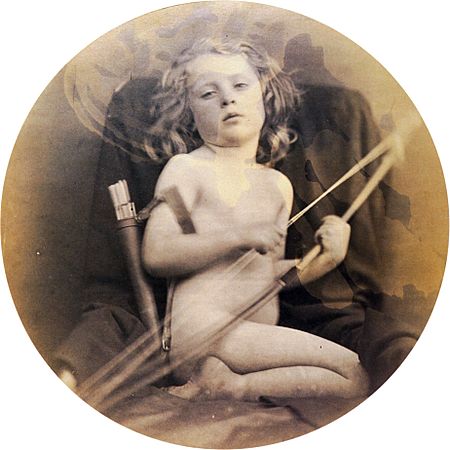

Portraits of Children

Children were often models for Cameron. These included her own children, relatives' children, and local kids. Children were popular subjects in the Victorian era. Cameron saw them as innocent, kind, and noble. She often showed them as angels or children from Bible stories.

The children in her photos were not always easy to work with. They sometimes got bored, annoyed, or distracted. These moods often show up in her pictures.

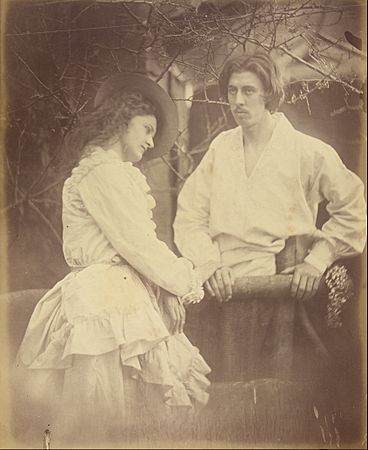

Allegories and Illustrations

Cameron may have found these story-like group portraits more challenging. With more people in the picture, someone was more likely to move during the long exposure times. More light was needed to shorten the exposure. More people also meant a greater depth of field was needed to keep everyone in focus. This made the pictures even harder to compose.

Cameron's story-telling portraits of women were inspired by living scenes (tableaux vivants) and amateur theatre. The women in her photos are usually shown in the ideal Victorian roles of mother and wife.

Religious Themes

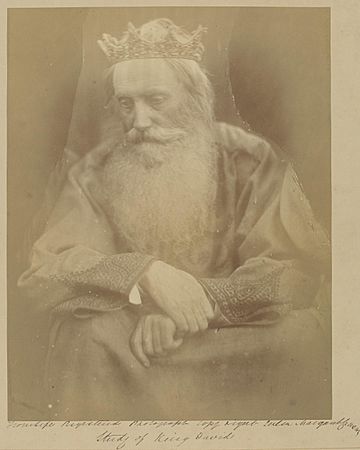

Cameron made over 50 photos showing the Madonna. Her household servant, Mary Hillier, often played this role. These photos show "an ideal of femininity that combines wholesomeness with qualities of sensuality and vulnerability." She showed the Virgin Mary in different Bible scenes. These included the Annunciation and the Salutation. She also created pictures of less known religious figures.

-

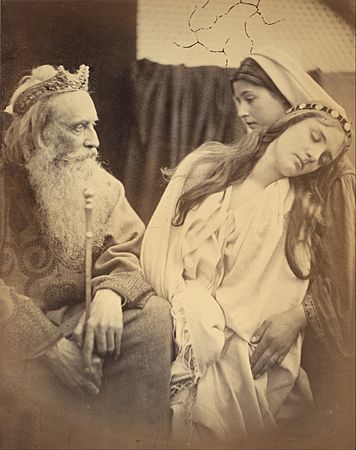

Sir Henry Taylor as King David 1866

Literary Inspirations

Cameron used literature as inspiration for her story-like photos. She showed characters from Shakespeare, Elizabethan poems, novels, and plays. She also used works by her friends, like Alfred Tennyson and Christina Rossetti.

Idylls of the King

In 1874, Alfred Tennyson asked Cameron to create pictures for a new edition of his Idylls of the King. This was a popular series of poems about Arthurian legends. Cameron worked on this project for three months. She took several photos in her famous soft focus style. She was not happy with the final book. She felt her small pictures lost their meaning. This led Cameron to publish a special, larger version of the Idylls of the King. It had twelve full-size photographs. This series was her last big project. It is seen as the best of her story-telling work.

Exhibitions of Her Work

Many museums have shown Julia Cameron's work over the years.

In 2013, the Metropolitan Museum of Art had a big exhibition of her photos. It received great reviews.

In 2015, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London held a show for her 200th birthday. This show used their large collection of her work. It also traveled to Sydney, Australia.

The National Portrait Gallery in London had an exhibition in March 2018. It showed her work alongside other Victorian photographers. These included Lady Clementina Hawarden and Lewis Carroll.

Here are some past exhibitions that focused on Cameron's work:

| Title | Dates | Institution | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Julia Margaret Cameron | 16 December 1960 – 31 January 1961 | Limelight Gallery | United States |

| Mrs. Cameron's photographs from the life | 22 January 1974 – 10 March 1974 | Stanford University Museum of Art | United States |

| Whisper of the Muse | 10 September 1986 – 16 November 1986 | Getty Villa | United States |

| Whisper of the Muse at Loyola Marymount University | 12 September 1986 – 25 October 1986 | Laband Gallery | United States |

| Portrait Photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron | 25 November 1987 – 14 February 1988 | National Portrait Gallery | United States |

| Julia Margaret Cameron: The Creative Process | 15 October 1996 – 5 January 1997 | Getty Villa | United States |

| 4 February 1998 – 3 May 1998 | Art Gallery of Ontario | Canada | |

| Julia Margaret Cameron: Nineteenth Century Photographic Genius | 6 February 2003 – 26 May 2003 | National Portrait Gallery, London | United Kingdom |

| 5 June 2003 – 30 August 2003 | National Media Museum | United Kingdom | |

| Julia Margaret Cameron, Photographer | 21 October 2003 – 11 January 2004 | Getty Center | United States |

| Julia Margaret Cameron | 19 August 2013 – 5 January 2014 | Metropolitan Museum of Art | United States |

| Julia Margaret Cameron | 15 August 2015 – 25 October 2015 | Art Gallery of New South Wales | Australia |

| Julia Margaret Cameron: Influence and Intimacy | 24 September 2015 – 28 March 2016 | Science Museum, London | United Kingdom |

| Julia Margaret Cameron | 28 November 2015 – 21 February 2016 | Victoria and Albert Museum | United Kingdom |

| Julia Margaret Cameron: A Woman who Breathed Life into Photographs | 2 July 2016 – 19 September 2016 | Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum | Japan |

Albums of Her Work

Cameron created several photo albums. These were often dedicated to friends or family.

| Title | Dedication date |

|---|---|

| Mia Album | 7 July 1863 |

| Watts Album | 22 February 1864 |

| Herschel Album | 26 November 1864 |

| Overstone Album | 5 August 1865 |

| Lindsay Album | – |

| Thackeray Album | 1864 |

| Henry Taylor Album | – |

| Norman Album | 7 September 1869 |

| Aubrey Ashworth Taylor Album | 29 September 1869 |

Selected Publications

- Cameron, Julia Margaret (1973). Victorian photographs of famous men & fair women. Introductions by Virginia Woolf and Roger Fry. D. R. Godine. ISBN 978-0-87923-076-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZK4lAQAAIAAJ.

- Cameron, J. M. P. (1875). Illustrations by Julia Margaret Cameron of Alfred Tennyson's Idylls of the King and other poems

- Cameron, J. M. P. (1889). Unfinished autobiography "Annals of my glass house" by Julia Margaret Cameron, written 1874, first published 1889

- Cameron, J. M. (1975). The Herschel album: an album of photographs. London (2 St Martin's Place, WC2H 0HE): National Portrait Gallery

- Cameron, J. M., & Ford, C. (1975). The Cameron Collection: an album of photographs. Wokingham: Van Nostrand Reinhold for the National Portrait Gallery

- Cameron, J. M. P., & Weaver, M. (1986). Whisper of the muse: the Overstone album & other photographs. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum

See also

In Spanish: Julia Margaret Cameron para niños

In Spanish: Julia Margaret Cameron para niños