Lee Krasner facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lee Krasner

|

|

|---|---|

Krasner in 1983

|

|

| Born |

Lena Krassner

October 27, 1908 New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | June 19, 1984 (aged 75) New York City, U.S.

|

| Education | Cooper Union National Academy of Design Hans Hofmann |

| Known for | Painting, collage |

| Movement | Abstract expressionism |

| Spouse(s) | |

Lee Krasner (born Lena Krassner; October 27, 1908 – June 19, 1984) was an American abstract expressionist painter. She was especially good at creating collages. Lee Krasner was married to another famous artist, Jackson Pollock.

For a long time, people often focused more on Pollock's art. But Krasner's work is now seen as very important. She helped connect older art styles with new ideas in America after World War II. Her paintings are now very valuable. She was also one of the few women artists to have a special show at the Museum of Modern Art.

Contents

Early Life and Art Dreams

Lee Krasner was born Lena Krassner in Brooklyn, New York, on October 27, 1908. Her parents, Chane and Joseph Krasner, were Ukrainian-Jewish immigrants. They came to the United States to escape unfair treatment and war. Lee was the youngest of six children and the only one born in the U.S.

From a young age, Krasner knew she wanted to be an artist. When she was a teenager, she chose to go to Washington Irving High School because it offered an art major.

Krasner's Art Education

After high school, Krasner earned a scholarship to the Women's Art School of Cooper Union. There, she learned enough to get a teaching certificate in art. She continued her art studies at the National Academy of Design from 1928 to 1932.

Krasner gained a deep understanding of art techniques from her studies. She learned how to draw human figures very accurately. Not many of her early works still exist because most were lost in a fire. One painting that survived is her "Self Portrait" from 1930. She painted it outdoors and it shows her looking strong and determined.

In 1928, she also briefly attended the Art Students League of New York. There, she took a class with George Bridgman, who taught her a lot about the human body.

Learning Modern Art

The opening of the Museum of Modern Art in 1929 greatly influenced Krasner. She became interested in post-impressionism and started to question the traditional art styles she had learned. In the 1930s, she began studying modern art, focusing on how art is put together, different techniques, and art theories.

In 1937, she started taking classes from Hans Hofmann. He helped her change her approach to still life painting. Hofmann taught her to see the canvas as a flat surface. He showed her how to use color to create depth that wasn't like real life. During these classes, Krasner worked in a style called cubism, or neo-cubism. She often made charcoal drawings of people and colorful oil studies of still life scenes.

Hofmann once praised her work, saying, "This is so good, you would never know it was done by a woman." Another famous artist, Piet Mondrian, told her, "You have a very strong inner rhythm; you must never lose it."

Starting Her Art Career

During her studies, Krasner worked as a waitress. But during the Great Depression, it became hard to make a living. In 1935, she joined the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project. She worked in the mural division, helping to enlarge other artists' designs for public murals.

Krasner was happy to have a job, but she didn't enjoy working on other artists' figurative designs. She preferred abstract art. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, she made her own gouache sketches, hoping to create an abstract mural one day. However, her mural proposals were put on hold when the WPA shifted to creating war propaganda. Krasner then made collages for the war effort, which were displayed in department store windows.

She was also involved with the Artists Union, which helped her meet many other artists in New York City. In 1940, she joined the American Abstract Artists group. Here, she showed cubist still life paintings that were thick with paint and full of energetic brushstrokes. Through this group, she met many future abstract expressionists, including Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko.

Krasner's Art Style and Changes

Krasner is known as an abstract expressionist because her art was abstract, full of movement, and showed strong feelings. She worked with painting, collage, charcoal drawing, and sometimes mosaics. She often cut up her own drawings and paintings to make new collage works.

Krasner was very critical of her own art. She would often change or even destroy whole series of works. Because of this, not many of her pieces have survived. Her official list of works, published in 1995, includes 599 known pieces.

Her style changed often, which makes her work unique. She moved between structured and free-flowing art, clear shapes and open forms, and bright colors and single-color palettes. She didn't stick to one recognizable style. Instead, she embraced change in the mood, subject, texture, materials, and composition of her art.

Despite these changes, her works can often be recognized by their energetic brushwork, texture, rhythm, and natural shapes. Krasner was interested in herself, nature, and modern life, and these themes often appeared in her art. She believed her art came from her own personality and feelings.

Early 1940s Challenges

In the early 1940s, Krasner struggled to create art that satisfied her. She was greatly affected by seeing Pollock's work for the first time in 1942. This made her move away from Hofmann's cubist style, which required working from models. She called the paintings from this frustrating time her "grey slab paintings." She would work on them for months, adding and scraping off paint until the canvas was almost one color. She later destroyed most of these works.

In the fall of 1945, Krasner destroyed many of her cubist works from her studies with Hofmann. However, most of her paintings from 1938 to 1943 survived this period of reevaluation.

The Little Images (1946–1949)

In 1946, Krasner began her Little Image series, creating about 40 paintings until 1949. Some looked like mosaics with thick paint, others were "webbed" using a drip technique. Her "hieroglyph" paintings looked like a personal, unreadable script.

These works showed her move away from realistic figures. They covered the entire canvas, used energetic brushstrokes, and ignored natural colors. They had little color variation but were rich in texture due to thick paint. These are seen as her first successful works created purely from her imagination.

Some people think these images were Krasner's way of using Hebrew script. She later said she subconsciously painted from right to left, like Hebrew writing. Others believe these paintings showed her feelings about the tragedy of the Holocaust.

After finishing the Little Image series in 1949, Krasner again became critical of her work. She tried many new styles and destroyed most of what she made in the early 1950s. In 1950, she experimented with automatic painting, creating large, black-and-white, monster-like figures. When art dealer Betty Parsons saw these, she offered Krasner a show. But before the show, Krasner changed her style again to color field painting and destroyed the figurative works. This show was Krasner's first solo exhibition since 1945.

Early Collages (1951–1955)

By 1951, Krasner started her first series of collage paintings. She cut and tore shapes from her other works and pasted them onto large color field paintings. She worked on the floor instead of an easel. She would pin pieces to the canvas, arrange them, then paste them down and add color.

Many of these collages looked like plants or organic forms. By using different materials, she created interesting textures. The act of tearing and cutting showed her strong feelings. She explored contrasts like light and dark, soft and hard lines, and organic and geometric shapes. These collages marked her move towards art that hinted at figures or landscapes.

From 1951 to 1953, she mostly used ripped black ink drawings. Tearing the paper gave the edges a softer look than her earlier sharp shapes. From 1953 to 1954, she made smaller collages from pieces of unwanted works, sometimes even using Pollock's discarded splatter paintings. Some believe this showed her admiration for his art, while others saw it as a way to connect their works. By 1955, she made larger collages on different surfaces like wood or canvas.

The Earth Green Series (1956–1959)

In the summer of 1956, Krasner began her Earth Green Series. These works are thought to show her strong emotions about her relationship with Pollock, especially after his death. These large paintings feature mixed figures that look like plants and body parts. These shapes fill the canvas, making it dense and crowded.

The colors, often flesh tones with red accents, suggest wounds and pain. Paint drips on the canvas show her speed and willingness to let go of complete control, which helped her express her feelings. By 1957, her figures became more floral and used brighter, contrasting colors.

In 1958, Krasner was asked to create two abstract murals for an office building. She made two collage designs with floral patterns, but these murals were later destroyed in a fire.

The Umber Series (1959–1961)

Krasner created her Umber Series paintings when she was having trouble sleeping. She worked at night, using artificial light, which made her colors shift from bright to dull browns, grays, and blacks. She was also dealing with the recent deaths of Pollock and her mother. This led to an aggressive style in these paintings.

These large paintings show strong contrasts between dark and light. Her energetic brushwork is clear from the paint drips and splatters. There's no single focal point, making the composition feel very active. To paint such large works, she tacked the canvas to a wall. These images are often seen as violent and stormy landscapes.

The Primary Series (1960s)

By 1962, Krasner started using bright colors again, hinting at floral and plant shapes. These works were large and rhythmic, like her monochrome paintings, with no central focus. Their colors often clashed, suggesting tropical landscapes.

In 1963, she broke her right wrist after a fall. She still wanted to paint, so she started using her left hand. To make it easier, she sometimes squeezed paint directly from the tube onto the canvas, leaving large white areas. The movement and energy in these works became more controlled.

After her arm healed, Krasner created bright, decorative paintings that were less aggressive. These often looked like calligraphy or floral designs. They connected different brushstrokes into a single pattern.

In the second half of the 1960s, art critics began to see Krasner's important role in the New York School. Before this, her art was often overlooked because of her relationship with Pollock. Her first major exhibition was held in London in 1965, and it was well-received.

In 1969, Krasner focused on works on paper using gouache. These were called Earth, Water, Seed, or Hieroglyphics and sometimes looked like a Rorschach test.

Later Career Works

In the 1960s and 1970s, Krasner's work was influenced by postmodern art. She began making large horizontal paintings with sharp lines and a few bright, contrasting colors. She painted in this style until about 1973.

Three years later, she started her second series of collage images. She found old charcoal drawings from 1937 to 1940 while cleaning her studio. She decided to use most of them in new collages. In these works, the black and gray shapes of the old drawings stood out against the blank canvas or bright paint. The cut drawings were rearranged into curved shapes that looked like flowers.

This series was very popular when shown in 1977. It also showed how artists can reexamine and change their style as they get older to stay relevant.

Krasner and Pollock's Influence

Many people thought Krasner stopped working in the 1940s to support Pollock's career. But she never stopped creating art. She did shift her focus to help Pollock gain more recognition because she believed his art had "much more to give."

Throughout her career, Krasner went through periods of struggle. She would try new styles and be very critical, often changing or destroying her work. Because of this self-criticism, there are times when very few of her works exist, especially in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Krasner and Pollock greatly influenced each other's art. Krasner learned from Hans Hofmann about abstracting from nature and the flat nature of the canvas. Pollock learned from Thomas Hart Benton about complex design. Krasner's knowledge of modern art helped Pollock update his style, making his works more organized. She also introduced him to many artists, collectors, and critics.

Pollock helped Krasner become less restricted in her work. He inspired her to stop painting from models and to express her inner feelings more freely and spontaneously.

Krasner faced challenges because she was a woman and Pollock's wife. When they showed art together in 1949, one reviewer said she "tidied up" her husband's style. Even with the rise of feminism, her career was often linked to Pollock's. She was sometimes called "Action Widow," a term that suggested female artists depended on their male partners. In the 1940s and 1950s, Krasner often didn't sign her works, or used only her initials "L.K." to avoid highlighting her gender or her status as a wife.

Legacy and Personal Life

Lee Krasner died on June 19, 1984, at age 75, due to health issues.

Six months after her death, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City held a special exhibition of her work. A review in The New York Times said it clearly showed Krasner's important place in the New York art scene. As of 2008, Krasner was one of only four women artists to have such a major show at MoMA.

Her personal papers were given to the Archives of American Art in 1985, where they can be studied by researchers. After her death, her home in East Hampton became the Pollock-Krasner House and Studio, which is open for public tours.

The Pollock-Krasner Foundation was also created in 1985. This foundation manages the art of both Krasner and Pollock. It also helps other artists who need financial support. Krasner's paintings have sold for high prices at auctions, showing their value and importance.

Relationship with Jackson Pollock

Krasner and Jackson Pollock met in 1942. She was curious about his work and wanted to meet him. By 1945, they moved to a farmhouse in The Springs, New York, and got married that summer.

They both continued to create art in their separate studios at the farmhouse. Krasner worked in an upstairs bedroom, while Pollock used the barn. When not working, they enjoyed cooking, gardening, and entertaining friends.

By 1956, their relationship became difficult. Krasner went to Europe to visit friends, but had to return quickly when Pollock died in a car crash while she was away.

Religion and Identity

Krasner grew up in an orthodox Jewish home in Brooklyn. Her father was very religious, and her mother managed the household. Krasner appreciated parts of Judaism, like Hebrew script and religious stories.

As a teenager, she started to question what she saw as unfair treatment of women in orthodox Judaism. She recalled reading a prayer where men thanked God for creating them in His image, but women only thanked God for creating them "as You saw fit." She also began reading existentialist philosophies, which further distanced her from Judaism.

Although she married Pollock in a church, Krasner continued to identify as Jewish but chose not to practice the religion. Her Jewish identity has influenced how some scholars interpret her art.

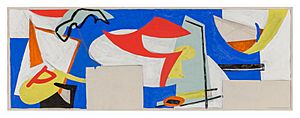

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Lee Krasner para niños

In Spanish: Lee Krasner para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |