Baldassare Castiglione facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Baldassare Castiglione

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione by Raphael

|

|

| Born | 6 December 1478 near Casatico, Margravate of Mantua |

| Died | February 2, 1529 (aged 50) Toledo, Spanish Empire |

| Occupation | Courtier, diplomat, soldier, author |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Literary movement | Renaissance |

| Notable works | The Book of the Courtier |

Baldassare Castiglione, Count of Casatico, was an important Italian writer, diplomat, and soldier during the Renaissance period. He was born on December 6, 1478, and passed away on February 2, 1529.

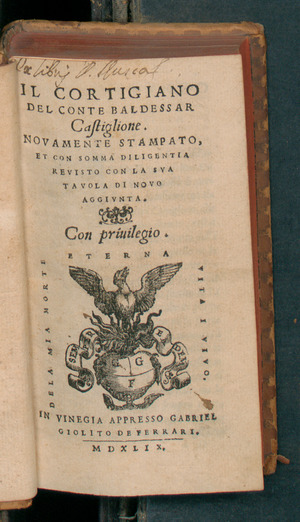

Castiglione is most famous for his book The Book of the Courtier (Il Cortegiano). This book was about how a perfect gentleman or lady should behave in a royal court. It taught about good manners, education, and morals. The book became very popular and influenced many people in Europe during the 1500s.

Contents

Baldassare Castiglione's Life Story

Castiglione was born in a small town called Casatico, near Mantua, Italy. His family was part of the minor nobility, and his mother was connected to the powerful Gonzaga family who ruled Mantua.

When he was 16, in 1494, Castiglione went to Milan to study. He learned from famous teachers like Demetrius Calcondila, who taught Greek. In 1499, his father died, and Baldassare had to return home to lead his family. He began working for the ruler of Mantua, Francesco II Gonzaga, and went on many official trips for him.

Life at the Urbino Court

In 1504, Castiglione moved to the court of Urbino. This court was known as one of the most elegant and cultured places in Italy. It was led by Duchess Elisabetta Gonzaga and her sister-in-law Emilia Pia. Many famous artists and writers visited Urbino, including Raphael, who painted portraits of the people there.

Guests at Urbino enjoyed intellectual discussions, parties, dances, concerts, and plays. Castiglione was inspired by Duchess Elisabetta and wrote poems for her. In 1506, he even wrote and acted in a play called Tirsi, which described the Urbino court.

Diplomatic Missions and Marriage

In 1508, a new Duke, Francesco Maria I della Rovere, took over in Urbino. Castiglione stayed at his court and even joined him in a military campaign. For his service, Castiglione was given the title of Count of Novilara.

Later, in 1512, Castiglione became an ambassador for Urbino in Rome. There, he became good friends with many artists and writers, including Raphael, who painted his famous portrait. This painting is now in the Louvre Museum.

In 1516, Castiglione returned to Mantua and married Ippolita Torelli. They had a deep love, but sadly, Ippolita died only four years later while Castiglione was away in Rome. After her death, Castiglione began a new career in the church.

Ambassador to Spain

In 1524, Pope Clement VII sent Castiglione to Spain as the ambassador for the Holy See. He followed the court of Emperor Charles V to different cities.

In 1527, Rome was attacked and looted. The Pope wrongly suspected Castiglione of not warning him about the Emperor's plans. Castiglione bravely wrote letters to both the Pope and the Emperor's secretary, explaining his actions and even criticizing the Vatican's own mistakes.

Despite the misunderstanding, Castiglione was cleared of blame. The Pope apologized, and the Emperor offered him a high position. Castiglione died of the plague in Toledo, Spain, in 1529. A monument was built for him in Mantua.

The Book of the Courtier: A Guide to Being a Renaissance Gentleman

Castiglione's most famous book, The Book of the Courtier (Il Libro del Cortegiano), was published in 1528. It is written as a conversation that takes place over four days in 1507 at the court of Urbino. The book describes what an ideal Renaissance gentleman should be like.

What Makes an Ideal Gentleman?

In the Middle Ages, a perfect gentleman was often a brave knight skilled in fighting. Castiglione's book changed this idea. He said that a perfect gentleman also needed a good education in Greek and Latin. He should be well-spoken and able to serve his country in both war and peace.

Castiglione's book was inspired by ancient Roman writers like Cicero. Cicero wrote about the ideal speaker, who was an honest and active citizen. The Courtier suggests that a gentleman should be educated not just for himself, but to help his community and advise rulers.

The Art of Sprezzatura

One key idea in the book is sprezzatura. This means making everything you do look easy and natural, even if it took a lot of effort. It's like an art that hides the art. For example, a courtier should be good at sports, telling jokes, fighting, writing poetry, playing music, drawing, and dancing. But he should do all these things without seeming to try too hard.

The book also discusses whether a perfect courtier needs to be born noble. While it's easier if you are, the characters in the book agree that anyone can learn to be noble through practice and by copying good examples.

Skills and Manners

The ideal courtier should be able to talk politely with everyone. He should know a lot about Greek and Latin literature. The book also mentions that the French, who had invaded Italy, sometimes looked down on educated people. Castiglione's characters believed that being educated was very important.

The book also talks about how a courtier should dress and behave. He should appear humble and avoid arrogance. The discussions also cover topics like the best form of government (republic or monarchy) and what kind of jokes are appropriate.

Music and the Court Lady

Music is another important topic. The book says that a courtier should be able to read music and play instruments. It explains that music can calm the soul and lift spirits. Even great ancient leaders and philosophers, like Socrates, learned music. Music helps people develop harmony and good character.

The book also discusses the "Court Lady" and the equality of men and women. One character, Gaspare Pallavicino, at first says women are only good for having children. But another character, Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici, strongly defends women. He points out that many women throughout history have been great philosophers, warriors, and rulers. In the end, Pallavicino admits he was wrong.

The book finishes with a speech about love by the scholar Pietro Bembo. He talks about a noble, non-physical kind of love that leads a person to appreciate beauty and spiritual ideas, eventually leading to God.

The Book's Big Impact

The Book of the Courtier became incredibly popular. It was quickly translated into many languages, including Spanish, German, French, and English. More than a hundred editions were published between 1528 and 1616 alone!

Castiglione's ideas about how an ideal gentleman should be educated and behave became a guide for the upper classes across Europe for centuries. In England, the book was translated by Sir Thomas Hoby in 1561 and influenced writers like William Shakespeare. Many people believed that studying The Book of the Courtier was more helpful than traveling for years.

Other Writings by Castiglione

Castiglione also wrote other works, though they are less known. These include love poems for Elisabetta Gonzaga, written in the style of Petrarch. He also wrote Latin poems, including one about the death of his friend Raphael. His letters are also very important because they tell us a lot about him, the famous people he met, and his diplomatic work. They are a valuable source for historians.

See also

In Spanish: Baltasar Castiglione para niños

In Spanish: Baltasar Castiglione para niños