Louise Nevelson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louise Nevelson

|

|

|---|---|

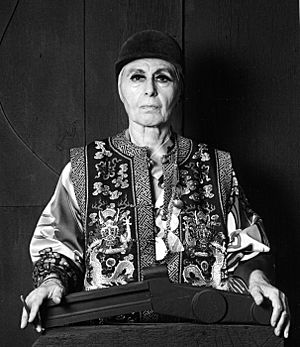

Nevelson in 1976

|

|

| Born |

Leah Berliawsky

September 23, 1899 Pereiaslav, Poltava Governorate, Russian Empire

|

| Died | April 17, 1988 (aged 88) New York City, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Awards |

|

Louise Nevelson (September 23, 1899 – April 17, 1988) was an American sculptor. She was famous for her huge, single-color wooden wall art and outdoor sculptures.

Born in the Poltava Governorate of the Russian Empire (now part of Ukraine), she moved with her family to the United States in the early 1900s. Nevelson learned English at school, as she spoke Yiddish at home.

By the early 1930s, she was taking art classes at the Art Students League of New York. In 1941, she had her first art show all by herself. Nevelson studied with famous artists like Hans Hofmann and Chaim Gross. She experimented with early conceptual art using everyday found objects. She also tried painting and printing before deciding to focus on sculpture.

Her sculptures were usually made from wood. They often looked like puzzles, with many carefully cut pieces put together. These pieces formed large wall sculptures or stood on their own. They were often three-dimensional. The sculptures were typically painted in one color, like black or white. Nevelson was a well-known artist around the world. Her art was shown at the 31st Venice Biennale, a big art exhibition. Her work can be seen in major museums and company collections. Nevelson is still one of the most important artists in 20th-century American sculpture.

Contents

Growing Up and Early Life

Louise Nevelson was born Leah Berliawsky in 1899 in Pereiaslav, Russian Empire. Her parents were Minna Sadie and Isaac Berliawsky. Isaac was a builder and sold wood. Even though her family lived comfortably, many of Nevelson's relatives had already moved to America. Isaac, being the youngest brother, had to stay behind to care for his parents.

While still in Europe, Minna gave birth to two of Nevelson's siblings: Nathan (born 1898) and Anita (born 1902). After his mother passed away, Isaac moved to the United States in 1902. Minna and the children then moved closer to Kiev. Family stories say that young Nevelson was so sad about her father leaving that she didn't speak for six months.

In 1905, Minna and the children moved to the United States. They joined Isaac in Rockland, Maine. Isaac had a hard time at first, feeling very sad as the family settled into their new home. He worked cutting wood before opening a junkyard. Working with wood meant it was always around the family. This material later became very important in Nevelson's art. Eventually, Isaac became a successful lumberyard owner and real estate agent. The family had another child, Lillian, in 1906. Nevelson was very close to her mother, who also struggled emotionally. This was thought to be because of the big move from Russia and being a Jewish family in Maine. Her mother tried to make up for this by dressing herself and the children in fancy clothes. Nevelson said her mother's "dressing up" was "art, her pride, and her job."

Nevelson first saw art at age nine at the Rockland Public Library. There, she saw a plaster cast of Joan of Arc. Soon after, she decided she wanted to study art. She took drawing classes in high school, where she was also the basketball captain. She painted watercolor pictures of rooms. In these, furniture looked like tiny parts, similar to her later sculptures. Female figures often appeared in her early art. In school, she practiced English, her second language, as Yiddish was spoken at home. Nevelson was not happy with her family's money situation, language differences, and unfair treatment because they were Jewish. She decided she wanted to move to New York for high school.

She finished high school in 1918. She then started working as a stenographer at a law office. There, she met Bernard Nevelson, who owned a shipping business with his brother Charles. Bernard introduced her to Charles, and Louise and Charles Nevelson got married in June 1920. This was a Jewish wedding in Boston. She had met her parents' wish for her to marry into a rich family. She and her husband moved to New York City. There, she began to study painting, drawing, singing, acting, and dancing. She also became pregnant, and in 1922, she gave birth to her son Myron (later called Mike). He also grew up to be a sculptor. Nevelson studied art even though her husband's parents did not approve. She once said, "My husband's family was terribly refined. Within that circle you could know Beethoven, but God forbid if you were Beethoven."

In 1924, the family moved to Mount Vernon, New York. This was a popular area for Jewish families. Nevelson was unhappy with the move because it took her away from city life and her art world. In the winter of 1932–1933, she separated from Charles. She did not want to be the socialite wife he expected. She never asked Charles for money. In 1941, they divorced.

Her Artistic Journey

Starting Out in the 1930s

Starting in 1929, Nevelson studied art full-time at the Art Students League. She said that seeing an exhibition of Noh kimono at the Metropolitan Museum of Art made her want to study art more. In 1931, she sent her son Mike to live with family. She went to Europe, paying for the trip by selling a diamond bracelet her ex-husband had given her when Mike was born. In Munich, she studied with Hans Hofmann before visiting Italy and France.

She returned to New York in 1932 and again studied with Hofmann. He was a guest teacher at the Art Students League. In 1933, she met Diego Rivera and helped him with his mural Man at the Crossroads at Rockefeller Plaza. Nevelson also started taking sculpture classes with Chaim Gross.

Nevelson kept trying other art forms, like lithography and etching. But she decided to focus on sculpture. Her first works were made from plaster, clay, and tattistone. In the 1930s, Nevelson started showing her art in group exhibitions. In 1935, she taught mural painting in Brooklyn. This was part of a government program called the Works Progress Administration (WPA). She worked for the WPA until 1939. In 1936, Nevelson won her first sculpture competition in New York. For several years, Nevelson and her son were very poor. They walked the streets collecting wood to burn for warmth. This firewood became the starting point for the art that made her famous. Her work in the 1930s included sculpture, painting, and drawing. Nevelson also made terra-cotta animals and oil paintings that were partly abstract.

First Shows and the 1940s

In 1941, Nevelson had her first solo art show at Nierendorf Gallery. The gallery owner, Karl Nierendorf, showed her work until he died in 1947. While at Nierendorf, Nevelson found a shoeshine box belonging to a local shoeshiner. She displayed the box at the Museum of Modern Art. This brought her the first big attention from the press. An article about her appeared in Art Digest in November 1943.

In 1943, Nevelson showed her work in Peggy Guggenheim's exhibition Exhibition by 31 Women in New York. In the 1940s, she started making Cubist figure studies. She used materials like stone, bronze, terra cotta, and wood. In 1943, she had a show called The Clown as the Center of his World. For this, she made circus sculptures from found objects. The show was not very popular. Nevelson stopped using found objects until the mid-1950s. Even with the poor reception, Nevelson's art at this time explored different styles. These included abstract figures inspired by Cubism and the experimental ideas of surrealism. This decade gave Nevelson the materials, art movements, and experiments that would shape her unique modernist style in the 1950s.

Mid-Career Success

During the 1950s, Nevelson showed her art as much as she could. Even with awards and growing popularity among art critics, she still struggled with money. To earn enough, she started teaching sculpture classes to adults. Her own art began to grow much larger. It moved beyond the human-sized works she had made in the early 1940s. Nevelson also visited Latin America. She found ideas for her work in Mayan ruins and the tall stone carvings of Guatemala.

In 1954, Nevelson's street in New York was set to be torn down. Her increasing use of scrap materials in the coming years came from things left on the streets by her neighbors who had to move out. In 1955, Nevelson joined Colette Roberts' Grand Central Modern Gallery. There, she had many solo shows. She showed some of her most famous works from this time. These included Bride of the Black Moon, First Personage, and the exhibit "Moon Garden + One." This show featured her first wall piece, Sky Cathedral, in 1958.

From 1957 to 1958, she was the president of the New York Chapter of Artists' Equity. In 1958, she joined the Martha Jackson Gallery. This gave her a guaranteed income, making her financially secure. That year, she was on the cover of Life magazine. She also had her first solo show at Martha Jackson. In 1960, she had her first solo show in Europe, in Paris. Later that year, a collection of her work called "Dawn's Wedding Feast" was part of a group show at the Museum of Modern Art. In 1962, the Whitney Museum of American Art bought her black wall sculpture, Young Shadows. That same year, her work was chosen for the 31st Venice Biennale. She also became the national president of Artists' Equity, serving until 1964.

In 1962, she left Martha Jackson Gallery for a short time at the Sidney Janis Gallery. After a first show where none of her art sold, Nevelson had a disagreement with the gallery owner, Janis, over money he had given her. Nevelson and Janis had a difficult legal argument that left Nevelson without money, feeling very sad, and at risk of losing her home. However, at this time, Nevelson was offered a paid art fellowship in Los Angeles. This allowed her to escape the problems in New York City. She said, "I wouldn't ordinarily have gone. I didn't care so much about the idea of prints at that time but I desperately needed to get out of town and all of my expenses were paid."

At the workshop, Nevelson made twenty-six lithographs. She became the most productive artist to complete the fellowship at that time. The lithographs she created were some of her most creative graphic works. She used unusual materials like cheesecloth, lace, and fabrics on the printing stone to make interesting textures. With new creative ideas and more money, Nevelson returned to New York in better personal and professional shape. She joined Pace Gallery in the fall of 1963. She had regular shows there until the end of her career. In 1967, the Whitney Museum held the first big show of Nevelson's work. It showed over one hundred pieces, including drawings from the 1930s and new sculptures. In 1964, she created two works, Homage to 6,000,000 I and Homage to 6,000,000 II. These were a tribute to victims of The Holocaust. Nevelson hired several assistants over the years to help in the studio and with daily tasks. By this time, Nevelson had become very successful and well-known.

Later Career and Life

Nevelson continued to use wood in her sculptures. But she also tried other materials like aluminum, plastic, and metal. Black Zag X from 1969, in the collection of the Honolulu Museum of Art, is an example of her all-black assemblages. It includes the plastic material, Formica. In the fall of 1969, Princeton University asked her to create her first outdoor sculpture. After finishing her first outdoor sculptures, Nevelson said, "Remember, I was in my early seventies when I came into monumental outdoor sculpture... I had been through the enclosures of wood. I had been through the shadows. I had been through the enclosures and come out into the open." Nevelson also liked new materials like plexiglas and cor-ten steel. She called them a "blessing." She liked the idea that her works could last in different weather. She also liked the freedom of making bigger art. These public artworks were made by the Lippincott Foundry. Nevelson's public art projects earned her a lot of money. However, some art historians say these pieces were not her strongest.

In 1969, Nevelson received the Edward MacDowell Medal.

In 1973, the Walker Art Center organized a big exhibition of her work. It traveled for two years. In 1975, she designed the chapel of St. Peter's Lutheran Church in Midtown Manhattan. When asked about being a Jewish artist creating Christian-themed art, Nevelson said her abstract work went beyond religious differences. Also in 1975, she created and installed a large wood sculpture called Bicentennial Dawn. It was placed at the new James A. Byrne United States Courthouse in Philadelphia.

During the last half of her life, Nevelson became even more famous. She developed a unique personal style for herself. She was small but wore dramatic dresses, scarves, and large false eyelashes. This style added to her legacy. The designer Arnold Scaasi created many of her clothes. Nevelson passed away on April 17, 1988.

When her friend Willy Eisenhart died in 1995, he was working on a book about Nevelson.

Upon Nevelson's death, her estate was worth at least $100 million. Her son, Mike Nevelson, took 36 sculptures from her house. Documents showed that Nevelson had given these works, worth millions, to her friend and assistant of 25 years, Diana MacKown. But Mike Nevelson claimed otherwise. A legal process began about the estate and will. Mike Nevelson claimed the will did not mention MacKown.

In 2005, Maria Nevelson, Louise's youngest granddaughter, started the Louise Nevelson Foundation. This group works to teach people about Louise Nevelson's life and art. Maria Nevelson often gives talks about her grandmother at museums and helps with research.

Nevelson and Feminist Art

Louise Nevelson played a key role in the feminist art movement. She helped change how people thought about art made by women. Her dark, huge, and totem-like artworks were often seen as "masculine" in culture. Nevelson believed that art showed the person who made it, not if they were male or female. She chose to be known as an artist, not just a female artist.

Reviews of Nevelson's art in the 1940s sometimes dismissed her as "just a woman artist." One reviewer of her 1941 show said, "We learned the artist is a woman, in time to check our enthusiasm. Had it been otherwise, we might have hailed these sculptural expressions as by surely a great figure among moderns." Another review showed similar unfair treatment: "Nevelson is a sculptor; she comes from Portland, Maine. You'll deny both these facts and you might even insist Nevelson is a man, when you see her Portraits in Paint, showing this month at the Nierendorf Gallery."

Mary Beth Edelson's Some Living American Women Artists / Last Supper (1972) used Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper. She put the faces of famous women artists over the faces of Christ and his apostles. Nevelson was one of these women. This image, which talked about how religious and art history images treated women unfairly, became "one of the most iconic images of the feminist art movement."

Even with her influence on feminist artists, Nevelson thought that artists who didn't succeed because of their gender might lack confidence. When asked if she faced unfair treatment in the art world because she was a woman, Nevelson replied, "I am a woman's liberation." Don Bacigalupi, a former museum president, said about Nevelson, "In Nevelson's case, she was the most determined artist there was. She was the most forceful, the most difficult. She just forced her way in. And so that was one way to do it, but not all women chose to or could take that route."

Art Style and Works

When Nevelson was creating her unique style, many other artists were welding metal to make large sculptures. Nevelson decided to do something different. She looked for ideas on the streets and found them in wood. Nevelson's most famous sculptures are her "walls." These are wooden, wall-like collages made of many boxes and sections. They hold abstract shapes and found objects, like chair legs or parts of staircases. Nevelson called these big sculptures "environments." The wooden pieces were also discarded scraps, found in the streets of New York.

While Marcel Duchamp caused a stir with his Fountain (a urinal presented as art), Nevelson took found objects and spray-painted them. By doing this, she hid their original use or meaning. Nevelson called herself "the original recycler" because she used so many discarded items. She gave credit to Pablo Picasso for "giving us the cube," which helped her create her cubist-style sculptures. She was greatly influenced by Picasso's and Hofmann's cubist ideas. She called the Cubist movement "one of the greatest awarenesses that the human mind has ever come to." She also found inspiration in Native American and Mayan art, dreams, the cosmos, and ancient symbols. Another important influence, though less known, was Joaquín Torres García, a Uruguayan artist.

As a student of Hans Hofmann, she learned to create her art with a limited number of colors, like black and white. This was to "discipline" herself. These colors became a big part of Nevelson's art. She spray-painted her walls black until 1959. Nevelson said black was the "total color" that "means totality. It means: contains all... it contained all color. It wasn't a negation of color. It was an acceptance. Because black encompasses all colors. Black is the most aristocratic color of all. The only aristocratic color... I have seen things that were transformed into black, that took on greatness." In the 1960s, she started adding white and gold to her works. Nevelson said white was the color that "summoned the early morning and emotional promise." She called her gold phase the "baroque phase." This was inspired by being told as a child that America's streets would be "paved with gold." It also related to the idea of wealth, the Sun, and the Moon. Nevelson looked at the Noh robes and gold coin collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for ideas.

Through her art, Nevelson often explored themes from her complex past, busy present, and hoped-for future. A common symbol in Nevelson's work is the bride, as seen in Bride of the Black Moon (1955). The symbol of the bride referred to Nevelson's own choice to avoid marriage early in her life. It also showed her independence as a woman throughout her life. Her Sky Cathedral works often took years to create. Sky Cathedral: Night Wall, at the Columbus Museum of Art, took 13 years to build in her New York City studio. About the Sky Cathedral series, Nevelson said, "This is the Universe, the stars, the moon – and you and I, everyone."

Nevelson's work has been shown in many galleries, including the Anita Shapolsky Gallery in New York City, Margot Gallery in Lake Worth, Florida, and Woodward Gallery in New York.

Legacy and Influence

A sculpture garden, Louise Nevelson Plaza (40°42′27″N 74°00′29″W / 40.7076°N 74.0080°W), is located in Lower Manhattan. It features several of Nevelson's works. Nevelson gave her papers to the Archives of American Art in several parts from 1966 to 1979. They are now fully available online. The Farnsworth Art Museum, in Nevelson's childhood home of Rockland, Maine, has the second largest collection of her works. This includes jewelry she designed.

In 2000, the United States Postal Service released a series of stamps to honor Nevelson. The next year, her friend and playwright Edward Albee wrote a play called Occupant as a tribute to the sculptor. The show opened in New York in 2002 with Anne Bancroft playing Nevelson. However, it did not go beyond previews because Bancroft became ill. Washington DC's Theater J brought the play back in November 2019. Nevelson's unique and striking look has been captured by photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe, Richard Avedon, Hans Namuth, and Pedro E. Guerrero. Nevelson is honored on the Heritage Floor, among other famous women, in Judy Chicago's 1974–1979 artwork The Dinner Party.

In 2005, Maria Nevelson, Louise's youngest granddaughter, started the Louise Nevelson Foundation. This non-profit group aims to teach the public about Louise Nevelson's life and work. It helps to continue her legacy and her important place in American Art History. Maria Nevelson gives many talks about her grandmother at museums and helps with research.

See also

In Spanish: Louise Nevelson para niños

In Spanish: Louise Nevelson para niños

- List of Louise Nevelson public art works

- Neith Nevelson, her granddaughter, also an artist

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |