Emily Carr facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Emily Carr

|

|

|---|---|

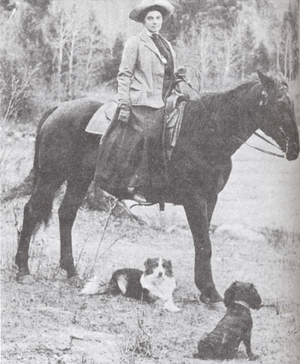

Carr in 1888

|

|

| Born |

Millie Emily Carr

December 13, 1871 Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

|

| Died | March 2, 1945 (aged 73) Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

|

| Education |

|

| Known for | Painting (The Indian Church, Big Raven), writing (Klee Wyck) |

| Movement | Modernism, Post-Impressionism, Expressionism |

Emily Carr (born December 13, 1871 – died March 2, 1945) was a famous Canadian artist and writer. She was deeply inspired by the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast and the beautiful forests of British Columbia. Emily Carr was one of the first painters in Canada to use a Modernist and Post-Impressionist style. At first, her art wasn't widely known, but later she became famous, especially for her forest paintings. She also wrote several books about her life and experiences in British Columbia. Many people see her as a true Canadian icon.

Contents

- Early Life and Art Training

- Discovering Indigenous Culture

- Studying Art in France

- Returning to Canada and New Challenges

- Growing Recognition for Her Art

- Working with the Group of Seven

- Influence of the Pacific Northwest Art Style

- Later Life and Writing

- Emily Carr's Art and Legacy

- Recognition and Legacy

- Places Named After Emily Carr

- See also

Early Life and Art Training

Emily Carr was born in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1871. She was one of nine children born to English parents, Richard and Emily Carr. Her family lived in a large, English-style home in Victoria. Emily was raised with traditional English customs and a strong focus on the Presbyterian church.

Emily's mother passed away in 1886, and her father died in 1888. After her parents' deaths, Emily decided to seriously pursue her passion for art. She studied at the San Francisco Art Institute for two years, from 1890 to 1892. Later, in 1899, she traveled to London, England, to study at the Westminster School of Art. She also visited an Indigenous mission in Ucluelet, on Vancouver Island, in 1898.

After returning to British Columbia in 1905, Emily took a job teaching art in Vancouver. However, she wasn't very popular as a teacher, and her students sometimes avoided her classes.

Discovering Indigenous Culture

In 1898, when Emily was 27, she began taking trips to Aboriginal villages to sketch and paint. She stayed in a village near Ucluelet, home to the Nuu-chah-nulth people. This experience left a strong impression on her. Her interest in Indigenous life grew even more after a trip to Alaska with her sister Alice nine years later.

In 1912, Emily went on another sketching trip to First Nations villages in Haida Gwaii, along the Upper Skeena River, and in Alert Bay. Even after she left these villages, the impact of the people and their art stayed with her. Emily even adopted an Indigenous name, Klee Wyck, which means "laughing one." She later used this name as the title for one of her books.

In 1913, Emily held a big art show featuring her paintings of First Nations villages and totem poles. She gave a lecture where she explained that every pole in her collection was studied directly from real life.

Studying Art in France

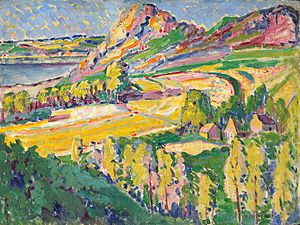

To learn more about new art styles, Emily Carr returned to Europe in 1910. She studied at the Académie Colarossi in Paris, France. While there, she met a modernist painter named Harry Gibb. Emily and her sister were amazed by his use of bright colors and how he changed shapes in his art.

Studying with Gibb greatly influenced Emily's painting style. She started using a much brighter color palette instead of the softer, pastel colors she had learned in Britain. Emily was also inspired by the Post-Impressionists and Fauvists she met in France. When she came back to Canada in 1912, she held an exhibition of her new works. She was the first artist to bring the Fauvist style to Vancouver.

Returning to Canada and New Challenges

In March 1912, Emily opened an art studio in Vancouver. However, local people didn't really understand or support her bold new style, with its bright colors and less detail. Because of this, she closed her studio and moved back to Victoria.

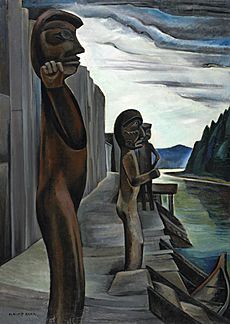

In the summer of 1912, Emily traveled north again to Haida Gwaii and the Skeena River. There, she continued to document the art of the Haida, Gitxsan, and Tsimshian peoples. She painted a carved raven, which later became her famous painting Big Raven. Another painting, Tanoo, shows three totem poles in front of houses in the village of the same name.

Even though some people liked her new "French" style, Emily felt that Vancouver wasn't ready to support her art career. She wrote about this in her book Growing Pains. She decided to stop teaching and working in Vancouver, and in 1913, she returned to Victoria, where her sisters lived.

For the next 15 years, Emily didn't paint much. She ran a boarding house called the 'House of All Sorts', which later inspired another one of her books. During this time, she painted only a few local scenes, like the cliffs at Dallas Road or trees in Beacon Hill Park. She felt that art was no longer the main focus of her life.

Growing Recognition for Her Art

Over time, Emily Carr's art started to get noticed by important people. One of them was Marius Barbeau, a well-known expert on cultures at the National Museum in Ottawa. Barbeau convinced Eric Brown, the Director of Canada's National Gallery, to visit Emily in 1927.

Brown invited Emily to show her work at the National Gallery as part of an exhibition about West Coast Aboriginal art. Emily sent 26 oil paintings, along with some of her pottery and rugs with Indigenous designs. This exhibition, which also included works by other artists, traveled to Toronto and Montreal.

Emily continued to travel in the late 1920s and 1930s. Her last trip north was in 1928, when she visited the Nass and Skeena rivers, as well as Haida Gwaii. She also traveled to other places in British Columbia. Her art became more and more recognized, and her work was shown in major cities around the world, including London, Paris, and Amsterdam. In 1935, Emily had her first solo art show in eastern Canada.

Working with the Group of Seven

At the West Coast Aboriginal art exhibition in 1927, Emily Carr met members of the Group of Seven. This group included Canada's most famous modern painters at the time. Lawren Harris from the Group became a very important supporter for Emily. He told her, "You are one of us," which made her feel accepted among Canada's leading modern artists.

This meeting ended Emily's artistic isolation of the past 15 years. It led to one of her most productive periods, where she created many of her most famous works. Through her letters with Harris, Emily also learned about and studied Northern European symbolism.

The Group of Seven, especially Lawren Harris, influenced Emily's art. Harris believed in Theosophy, a spiritual philosophy. Emily struggled to connect this with her own ideas about God. She didn't trust traditional religion and started to see God in nature itself. She painted wild Canadian landscapes, showing them as if they were filled with a greater spirit.

Influence of the Pacific Northwest Art Style

In 1924 and 1925, Emily Carr showed her art at the Artists of the Pacific Northwest shows in Seattle, Washington. Another artist from the show, Mark Tobey, visited her in Victoria in 1928 to teach an advanced art course in her studio.

Working with Tobey helped Emily understand modern art even better. She experimented with his methods of abstract art and Cubism. While she was hesitant to go fully abstract, her work from this time started to focus less on just showing what things looked like. Instead, she tried to capture the feelings and myths hidden in the totem carvings. She changed her painting style to create more stylized and geometric shapes.

Later Life and Writing

Emily Carr had several heart attacks starting in 1937, and a serious stroke in 1940. These health issues made it hard for her to travel and paint as much. So, she started to focus more on her writing. With help from her friend Ira Dilworth, an English professor, Emily's first book, Klee Wyck, was published in 1941. She even won the Governor-General's Award for non-fiction for this book that same year.

Paintings from Emily's last ten years show her growing worry about how industries were affecting British Columbia's environment. Her art from this time reflected her concern about logging, its impact on nature, and how it affected Indigenous people's lives. For example, in her painting Odds and Ends (1939), she shows cleared land and tree stumps. This shifts the focus from beautiful forests to the effects of deforestation.

Emily Carr had her last heart attack and passed away on March 2, 1945, in her hometown of Victoria, British Columbia. She is buried at Ross Bay Cemetery.

Emily Carr's Art and Legacy

Painting Style and Themes

Emily Carr is mostly remembered for her paintings. She was one of the first artists to try and capture the spirit of Canada using a modern art style. Her main themes were Indigenous peoples and nature. She painted "native totem poles set in deep forest locations or abandoned native villages" and, later, "the large rhythms of Western forests, driftwood-tossed beaches and expansive skies." She combined these two themes in her own unique way.

At the California School of Design, Emily took art classes that covered many styles. While she studied drawing, portraits, still life, and flower painting, she liked painting landscapes the most.

Emily is well-known for her paintings of First Nations villages and Pacific Northwest totem poles. However, art historian Maria Tippett points out that Emily's unique way of showing the forests of British Columbia from within them makes her work stand out. She created a new way of understanding the Pacific Northwest, including how Indigenous people and Canadian landscapes were presented in art.

After visiting the Gitksan village of Kitwancool in 1928, Emily became fascinated by the motherly images in Pacific Northwest Indigenous totem poles. After seeing these images, her paintings started to show these themes of mother and child from Native carvings.

Her painting style changed over time. It can be divided into several periods: her early work before studying in Paris; her early paintings influenced by Fauvism from her time in Paris; a middle period influenced by Post-Impressionism before she met the Group of Seven; and her later, more formal period, influenced by Lawren Harris and Mark Tobey. Emily used charcoal and watercolor for her sketches. Later, she used house paint thinned with gasoline on paper, and for her most important works, oil on canvas.

In 2013, one of Emily's paintings, The Crazy Stair (The Crooked Staircase), sold for $3.39 million. This set a record price for a painting by a Canadian female artist.

Writing

Emily Carr is also remembered for her writing, especially about her Indigenous friends and her life. Besides Klee Wyck, she wrote The Book of Small (1942), The House of All Sorts (1944), and, published after she passed away, Growing Pains (1946), Pause (1953), The Heart of a Peacock (1953), and Hundreds and Thousands (1966). Some of these books are about her own life and show that she was a talented writer.

Recognition and Legacy

Emily Carr's life story itself made her a "Canadian icon." She was an artist with amazing originality and strength. She also became famous later in life, starting the work she is best known for at age 57. Emily succeeded even though she lived in a society that wasn't very open to new art styles and worked mostly alone, away from big art centers. This made her a favorite among those who support women in art.

Emily Carr brought the art and culture of the North to the South, and the West to the East. She gave new European settlers a glimpse into the ancient culture of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

In 1952, Emily Carr's artworks, along with those of other Canadian artists, represented Canada at the Venice Biennale, a major international art exhibition.

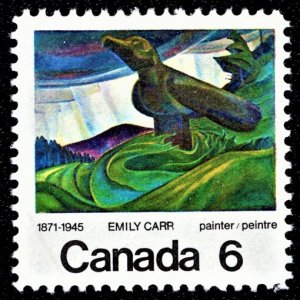

Canada Post has honored Emily Carr with stamps. In 1971, a 6¢ stamp featuring her painting Big Raven was issued. In 1991, a 50¢ stamp with her painting Forest, British Columbia was released.

In 1978, she received the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts Medal. In 2014–2015, the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, England, held a solo exhibition of her work, which was the first time such a show was held in Britain.

Emily Carr has been recognized as a Historic Person in Canada. There is even a minor planet, 5688 Kleewyck, named after her.

Places Named After Emily Carr

Many places are named after Emily Carr to honor her contributions:

- Emily Carr House in Victoria, British Columbia, her childhood home.

- Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, British Columbia.

- Emily Carr Public Library in Victoria, British Columbia.

- Emily Carr Secondary School in Woodbridge, Ontario.

- Emily Carr Elementary School in Vancouver, British Columbia.

- Emily Carr Middle School in Ottawa, Ontario.

- Emily Carr public schools in London, Toronto, and Oakville, Ontario.

- In 1994, a crater on Venus was named Carr crater, with a diameter of about 31.9 kilometers.

- Emily Carr Inlet, an arm of Chapple Inlet on the North Coast of British Columbia.

|

See also

In Spanish: Emily Carr para niños

In Spanish: Emily Carr para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |