Marius Barbeau facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

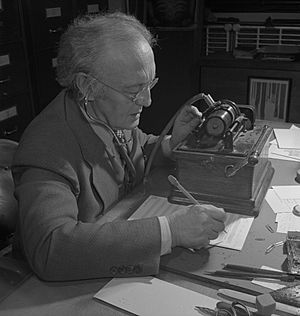

Charles Marius Barbeau

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | March 5, 1883 Ste-Marie-de-Beauce (later Sainte-Marie, Quebec, Canada

|

| Died | February 27, 1969 (aged 85) Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

|

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Occupation | ethnographer, folklorist |

| Awards | Order of Canada |

Charles Marius Barbeau (March 5, 1883 – February 27, 1969), often known simply as Marius Barbeau, was a Canadian ethnographer and folklorist. He is seen as one of the people who helped start the study of anthropology in Canada. An ethnographer studies different cultures and peoples. A folklorist studies the traditions, stories, and music of a group of people.

Marius Barbeau was famous for supporting the folk culture of Québec. He also carefully recorded the social life, stories, music, and art of the Tsimshianic-speaking peoples in British Columbia. These groups include the Tsimshian, Gitxsan, and Nisga'a, as well as other Northwest Coast peoples. He also had some unique ideas about how people first came to live in the Americas.

Some people have criticized Barbeau's work. They felt that he did not always show the full picture or accurately represent the Indigenous people he studied. For example, in his work with the Tsimshian and Huron-Wyandot, Barbeau was mainly looking for stories that he considered "authentic" and that did not have political meanings.

Contents

Life and Career

Early Life and Education

Frédéric Charles Joseph Marius Barbeau was born on March 5, 1883, in Sainte-Marie, Quebec. When he was 14, in 1897, he started studying to become a priest. He later changed his studies to law at Université Laval and earned his law degree in 1907.

After that, he received a special scholarship called a Rhodes Scholarship. This allowed him to study in England at Oriel College, Oxford from 1907 to 1910. There, he began to study new fields like anthropology, archeology, and ethnography. During his summers, he also attended schools in Paris, France. In Paris, he met Marcel Mauss, who encouraged him to study the traditional stories and customs of North American Indigenous peoples.

Field Work and Research

In 1911, Barbeau started working at the National Museum of Canada. This museum was part of the Geological Survey of Canada at the time. He worked there for his whole career, retiring in 1949.

At first, he and another anthropologist named Edward Sapir were the only two full-time anthropologists in Canada. Barbeau began his field work in 1911–1912. He worked with the Huron-Wyandot people in Quebec, southern Ontario, and Oklahoma in the United States. He collected many of their stories and songs.

In 1913, a German-American anthropologist named Franz Boas suggested that Barbeau focus on French-Canadian traditional culture. Barbeau started collecting this material the next year. In 1918, Barbeau became the president of the American Folklore Society.

In 1914, Barbeau married Marie Larocque, and they started a family.

Starting in December 1914, Barbeau spent three months doing field work in Lax Kw'alaams (Port Simpson), British Columbia. This was the largest Tsimshian village in Canada. He worked closely with his interpreter, William Beynon, who was a Tsimshian hereditary chief. Another anthropologist, Wilson Duff, later said these three months were "one of the most productive field seasons" in the history of North American anthropology.

Barbeau and Beynon worked together for many decades. Barbeau wrote a huge amount of notes from his field work. These notes are still mostly unpublished. Duff described them as "the most complete body of information on the social organization of any Indian nation." Barbeau even taught Beynon how to write down sounds, and Beynon became an important field worker himself. They continued their work with the Kitselas and Kitsumkalum Tsimshians and the Gitksan people in 1923–1924. In 1927 and 1929, they worked with the Nisga'a people.

In 1922, Barbeau helped start the Canadian Historical Association and became its first Secretary. In 1929, he also helped create the Royal Canadian Geographical Society.

Academic Career

In 1942, Barbeau started teaching at Laval University and the University of Ottawa. In 1945, he became a professor at Laval. He retired in 1954 after having a stroke. He passed away on February 27, 1969, in Ottawa.

Theories and Ideas

Barbeau also did some brief field work with other Indigenous groups on the Northwest Coast, such as the Tlingit, Haida, Tahltan, and Kwakwaka'wakw. However, he always focused more on the Tsimshian, Gitksan, and Nisga'a peoples. He tried to combine the different stories these peoples had about their migrations to understand how they settled in the Americas. He was one of the first to suggest that people migrated from Siberia across the Bering Strait into North America. Many Indigenous nations still disagree with this idea, as they believe they originated in North America.

One of his more debated ideas was that the Tsimshianic-speaking peoples, Haida, and Tlingit were the most recent groups to migrate to the New World from Siberia. He thought their ancestors might have been refugees from the conquests of Genghis Khan just a few centuries ago. This idea caused disagreements with many other experts at the time. Later studies of language and DNA have shown that his theory was incorrect.

Thanks to William Beynon, Barbeau helped Western academics understand that the oral histories (spoken stories) of migration from Indigenous peoples had real historical value. For a long time, these stories were not taken seriously because they didn't fit European ways of recording history. Barbeau and Beynon's idea has since been shown to have some truth, especially when combined with other evidence like climate, astronomy, and geology.

Barbeau was also an early supporter of recognizing totem poles as important works of art. However, his idea that totem poles were a new art form that developed only after contact with Europeans has been proven wrong.

Ethnomusicology and Music Collection

Barbeau's main contribution to ethnomusicology was collecting music. Ethnomusicology is the study of music from different cultures. He was interested in music from a young age and learned music from his mother. Throughout his career, he believed music was important for understanding anthropology. He was one of the first Canadians to be called an ethnomusicologist.

Barbeau wanted all Canadians to experience folk music. He often used trained Canadian musicians to perform folk music for a wider audience.

In 1915, Barbeau started the Museum's collection of French-Canadian songs. In 1916, he went on a trip along the St. Lawrence River to record every French-Canadian folk song he could find. He returned with notes for over 500 songs and some folk legends.

Recognition and Legacy

Cultural Impact

Barbeau wrote a lot of books and articles. Some were for experts, and others were for the general public, sharing Québecois and First Nations oral traditions. For example, his book The Downfall of Temlaham combined old Gitksan stories with more recent history. His book The Golden Phoenix and other collections shared French-Canadian folk and fairy tales for children.

His field work and writings on French-Canadian culture led to many popular and academic publications. His work is believed to have played a big part in the rise of Québecois nationalism (a sense of pride and identity for people in Quebec) in the late 20th century.

Awards and Honours

In 1950, Barbeau won the Lorne Pierce Medal from the Royal Society of Canada. In 1967, he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada, which is one of Canada's highest honours. In 1969, Barbeau Peak, the highest mountain in Nunavut, was named after him.

In 2005, Marius Barbeau's radio broadcasts and recordings were recognized as a MasterWork by the Audio-Visual Preservation Trust of Canada. His many personal papers are kept at the Canadian Museum of History.

In 1985, the Folklore Studies Association of Canada created the Marius Barbeau Medal. This medal is given to people who have made important contributions to Canadian folklore and ethnology.

Portrait

A bronze statue of Barbeau's head was made by the artist Eugenia Berlin. It is now part of the collection at the National Gallery of Canada.

Selected Works

- (1915) "Classification of Iroquoian radicals with subjective pronominal prefixes." Ottawa: Geological Survey of Canada. Memoir no. 46. GEOSCAN.

- (1915) Huron and Wyandot Mythology, with Appendix Containing Earlier Published Records. Ottawa: Geological Survey of Canada. Memoir no. 80. GEOSCAN.

- (1923) Indian Days in the Canadian Rockies. Illustrated by W. Langdon Kihn. Toronto: Macmillan.

- (with Edward Sapir) (1925) Folksongs of French Canada. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- (1928) The Downfall of Temlaham. Toronto: Macmillan.

- (1929) "Totem Poles of the Gitksan, Upper Skeena River, British Columbia." Ottawa: National Museum of Canada. Bulletin no. 61. GEOSCAN.

- (1933) "How Asia Used to Drip at the Spout into America," Washington Historical Quarterly, vol. 24, pp. 163–173.

- (1934) Au Coeur de Québec. Montréal: Zodiaque.

- (1934) Cornelius Krieghoff: Pioneer Painter of North America. Toronto: Macmillan.

- (1934) La merveilleuse aventure de Jacques Cartier. Montréal: A. Levesque.

- (1935) "Folk-songs of Old Quebec." Ottawa: National Museum of Canada. Bulletin no. 75. GEOSCAN.

- (1935) Grand'mère raconte. Montréal: Beauchemin.

- (1935) Il était une fois. Montréal: Beauchemin.

- (1936) The Kingdom Saguenay. Toronto: Macmillan.

- (1936) Québec, ou survit l'ancienne France (Quebec: Where Ancient France Lingers.) Québec City: Garneau.

- (with Marguerite and Raoul d'Harcourt) (1937) Romanceros du Canada. Montréal: Beauchemin.

- (1942) Maîtres artisans de chez-nous. Montréal: Zodiaque.

- (1942) Les Rêves des chasseurs. Montréal: Beauchemin.

- (with Grace Melvin) (1943) The Indian Speaks. Toronto: Macmillan.

- (with Rina Lasnier) (1944) Madones canadiennes. Montréal: Beauchemin.

- (1944) Mountain Cloud. Toronto: Macmillan.

- (1944–1946) Saintes artisanes. 2 vols. Montréal: Fides.

- (1945) "The Aleutian Route of Migration into America." Geographical Review, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 424–443.

- (1945) "Bear Mother." Journal of American Folklore, vol. 59, no. 231, pp. 1–12.

- (1945) Ceinture flechée. Montréal: Paysana.

- (1946) Alouette! Montréal: Lumen.

- (1947) Alaska Beckons. Toronto: Macmillan.

- (1947) L'Arbre des rèves (The Tree of Dreams). Montréal: Thérrien.

- (1950; reissued 1990) Totem Poles. 2 vols. (Anthropology Series 30, National Museum of Canada Bulletin 119.) Ottawa: National Museum of Canada. Reprinted, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull, Quebec, 1990. Individual chapters available in pdf on the website of the Canadian Museum of History.

- (1952) "The Old-World Dragon in America." In Indian Tribes of Aboriginal America: Selected Papers of the XXIXth International Congress of Americanists, ed. by Sol Tax, pp. 115–122. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- (1953) Haida Myths. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada.

- (1954) "'Totemic Atmosphere' on the North Pacific Coast." Journal of American Folklore, vol. 67, pp. 103-122.

- (1957) Haida Carvers in Argillite. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada.

- (1957) J'ai vu Québec. Québec City: Garneau.

- (1957) My Life in Recording: Canadian-Indian Folklore. Folkways Records

- (ed.) (1958) The Golden Phoenix and Other Fairy Tales from Quebec. Retold by Michael Hornyansky. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- (1958) Medicine-Men on the North Pacific Coast. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada.

- (1958) Pathfinders in the North Pacific. Toronto: Ryerson.

- (et al.) (1958) Roundelays: Dansons à la Ronde. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada.

- (1960) Indian Days on the Western Prairies. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada.

- (1960) "Huron-Wyandot Traditional Narratives: In Translations and Native Texts." National Museum of Canada Bulletin 165, Anthropological Series 47.

- (1961) Tsimsyan Myths. (Anthropological Series 51, National Museum of Canada Bulletin 174.) Ottawa: Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources.

- (1962) Jongleur Songs of Old Quebec. Rutgers University Press.

- (1965–1966) Indiens d'Amérique. 3 vols. Montréal: Beauchemin.

- (1968) Louis Jobin, statuaire. Montréal: Beauchemin.

- (1973) "Totem Poles of the Gitksan, Upper Skeena River, British Columbia." Ottawa: National Museum of Canada. Bulletin no. 61, (ed. Facsimile).

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |