Maria Sibylla Merian facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Maria Sibylla Merian

|

|

|---|---|

Maria Sibylla Merian portrayed by Jacob Marrel (1671 ), Kunstmuseum Basel

|

|

| Born | 2 April 1647 Free Imperial City of Frankfurt in the Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | 13 January 1717 (aged 69) |

| Occupation | Naturalist, biological illustrator |

| Known for | Documentation of butterfly metamorphosis, scientific illustration |

Maria Sibylla Merian (April 2, 1647 – January 13, 1717) was a talented German-born Swiss scientist and artist. She was one of the first Europeans to study insects by watching them closely in nature. Maria came from the famous Merian family in Frankfurt.

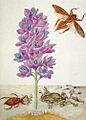

Maria learned art from her stepfather, Jacob Marrel, who was a student of a still life painter. She published her first book of nature drawings in 1675. Maria started collecting insects when she was a teenager. At 13, she even raised silkworms. In 1679, she published the first part of a book series about caterpillars. The second part came out in 1683. Each book had 50 detailed pictures that she made herself.

Maria showed how insects change through metamorphosis. She also recorded which plants 186 different European insects ate. Along with her amazing pictures, Maria wrote about the insects' full life cycles.

In 1699, Maria traveled to Dutch Surinam to study tropical insects. In 1705, she published her famous book, Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. This book greatly influenced other nature artists. Because of her careful work on butterfly metamorphosis, famous naturalist David Attenborough considers her a very important person in the study of insects, called entomology. Before her detailed work, many people thought insects just "appeared from mud" on their own.

Contents

Maria Sibylla Merian's Early Life and Career

Maria Sibylla Merian's father, Matthäus Merian the Elder, was a Swiss engraver and publisher. He married her mother, Johanna Sybilla Heyne, in 1646. Maria was born in 1647 and was his ninth child. Her father passed away in 1650. In 1651, her mother married Jacob Marrel, a painter of flowers and still lifes.

Marrel encouraged Maria to draw and paint. Even though he mostly lived in Holland, his student Abraham Mignon taught her. When she was 13, Maria painted her first pictures of insects and plants. She found these from specimens she had caught. From a young age, she had access to many books about natural history.

Maria wrote about her youth in her book Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium:

I spent my time investigating insects. At the beginning, I started with silkworms in my home town of Frankfurt. I realized that other caterpillars produced beautiful butterflies or moths, and that silkworms did the same. This led me to collect all the caterpillars I could find in order to see how they changed.

In May 1665, Maria married Johann Andreas Graff, who was Marrel's apprentice. His father was a poet and led a top school in 17th-century Germany. In January 1668, Maria had her first child, Johanna Helena. The family moved to Nuremberg, her husband's hometown, in 1670.

While in Nuremberg, Maria kept painting on parchment and linen. She also created designs for embroidery. She taught drawing lessons to daughters of rich families. This helped her family financially and improved their social standing. It also gave her access to beautiful gardens where she could collect and study insects. In 1675, Maria was recognized by Joachim von Sandrart's German Academy. Besides painting flowers, she made copperplate engravings. After studying at Sandrart's school, she published books with flower patterns. In 1678, she had her second daughter, Dorothea Maria.

Other women painters of the time included insects in their flower pictures. But they did not raise or study them as Maria did. In 1679, she published her first book on insects. It was the first of a two-part series showing insect metamorphosis.

In 1678, her family moved to Frankfurt am Main. However, her marriage was not happy. She moved in with her mother after her stepfather died in 1681. In 1683, she traveled to Gottorp. In 1685, Maria traveled with her mother, husband, and children to Friesland. Her half-brother Caspar Merian had lived there since 1677.

Life in Friesland

From 1685, Maria, her daughters, and her mother lived with a religious group called the Labadists. They lived at Walt(h)a Castle in Wieuwerd, Friesland. Maria stayed there for three years. She used this time to study nature and Latin, the language of science books. In the wet areas of Friesland, she watched how frogs were born and grew. She even collected and examined them. Maria lived with this community until 1691.

Moving to Amsterdam

In 1690, Maria's mother passed away. A year later, Maria moved with her daughters to Amsterdam. In 1692, her husband divorced her. In Amsterdam, her daughter Johanna married Jakob Hendrik Herolt. He was a successful merchant who traded with Suriname. The famous flower painter Rachel Ruysch became Maria's student.

Maria earned money by selling her paintings. She and her daughter Johanna sold flower pictures to art collectors like Agnes Block. By 1698, Maria lived in a nice house in Amsterdam.

In 1699, the city of Amsterdam allowed Maria to travel to Suriname in South America. Her younger daughter, Dorothea Maria, went with her. On July 10, the 52-year-old Maria and her daughter set sail. Their goal was to spend five years drawing new insect species. To pay for the trip, Maria Sibylla sold 255 of her own paintings. She later wrote:

In Holland, I was amazed by the beautiful animals from the East and West Indies. I was lucky to see the amazing collections of Doctor Nicolaes Witsen, the mayor of Amsterdam, and Mr. Jonas Witsen. I also saw collections from Mr. Frederick Ruysch, a doctor and professor, and Mr. Levinus Vincent, and many others. In these collections, I found countless insects. But I realized no one knew where they came from or how they reproduced. How do they change from caterpillars to chrysalises and so on? All of this made me want to take a long-dreamed-of journey to Suriname.

Journey to Suriname and Return

Maria arrived in Suriname on September 18 or 19. She met with the governor, Paulus van der Veen. She worked for two years, traveling around the colony. She sketched local animals and plants. She wrote down the local names for plants and how people used them.

Unlike other Dutch naturalists, Maria was not paid by a company for her trip. Her book about Suriname does not mention any sponsors. Some people think the directors of the Dutch West India Company might have paid for her journey. In her later book, Maria criticized the colonial merchants. She said they "had no desire to investigate anything like that; indeed they mocked me for seeking anything other than sugar in the country." Maria also spoke out against how merchants treated enslaved people. An enslaved person had to help Maria with her research. This help allowed her to talk with the Amerindian and African enslaved people in the colony. They helped her learn about the plants and animals of Suriname. Maria was also interested in farming. She was sad that colonial merchants only wanted to plant and export sugar. She later showed the many vegetables and fruits that could be found in Suriname, including the pineapple.

In June 1701, Maria became ill, possibly with malaria. This forced her to return to the Dutch Republic. Back in the Netherlands, Maria opened a shop. She sold the specimens she had collected and her drawings of plants and animals from Suriname. In 1705, she published her book Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium about the insects of Suriname.

In 1715, Maria had a stroke. Even though she was partly paralyzed, she kept working. She passed away in Amsterdam on January 13, 1717. She was buried four days later. Some say she died poor, but her funeral was a middle-class one with fourteen pall-bearers. After Maria's death, her daughter Dorothea published Erucarum Ortus Alimentum et Paradoxa Metamorphosis. This was a collection of her mother's work.

Maria Sibylla Merian's Amazing Work

Botanical Art and Illustrations

Maria Merian first became known as a botanical artist. In 1675, she began to publish a three-part series. Each part had 12 pictures of flowers. In 1680, she combined these into a book called Neues Blumenbuch.

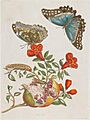

Her drawings were beautiful and decorative. Not all of them were drawn from real life. Some flowers in her books seem to be based on drawings by other artists. Maria included insects among the flowers. Again, she might not have seen all of them herself. Some might be copies of other drawings. The single flowers, wreaths, and bouquets in her books were used as patterns for artists and people who did embroidery. At that time, embroidery was an important part of a good education for young women in Europe. Copying other artists was a common way for artists to learn. Her designs looked like the popular embroidery patterns of the time. Butterflies and damselflies were shown with plants, similar to other decorative artworks. Her later books on caterpillars were also used as patterns for paintings, drawings, and sewing.

Maria also sold hand-colored versions of her flower books. She used vellum, a type of treated animal skin, and prepared it with a white layer. Because of the guild system, women were not allowed to paint with oil paints. So, Maria used watercolors and gouache instead.

Studying Insects and Their Life Cycles

Maria Merian was one of the first scientists to watch insects directly. She collected and observed live insects and made very detailed drawings. In her time, many people thought insects were "beasts of the devil." The process of metamorphosis (how insects change) was mostly unknown. While a few scholars had written about insect life cycles, most people believed insects just "appeared from mud" on their own. Maria showed evidence that this was not true. She described the life cycles of 186 different insect species.

Maria started collecting insects when she was a teenager. She kept a study journal. At 13, she raised silkworms and other insects. Her interest grew to include moths and butterflies, which she collected and studied. When she lived in Nuremberg and Frankfurt, Maria would travel to the countryside to find caterpillar larvae. She wrote down what plants they ate, when they changed, and what she saw them do. It was common for scientists to draw their own research. But Maria was one of the first trained artists to illustrate her lifelong studies.

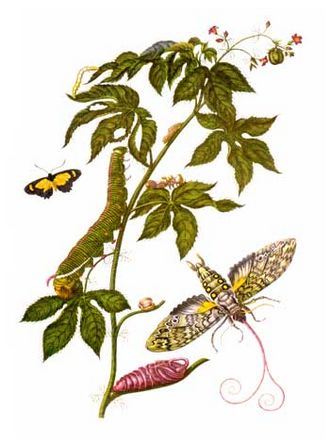

She watched insect life cycles for decades. She made detailed drawings based on live insects in their natural homes. This made her different from earlier artist-naturalists. Her drawings show moths laying eggs or caterpillars eating leaves. By drawing live insects, Maria could accurately show their colors. These colors would fade if the insects were preserved. The pictures she published are complex. They are based on detailed studies of individual insects she painted on vellum. Many of these are still in her study journal. She kept the exact posture and color of the insects when she put them into her larger pictures. While studying insects, she also drew the life cycle of flowers, from bud to fruit. As a trained artist, Maria cared about accurate colors. In her Metamorphosis book, she wrote down which plants could be used to make pigments. The engravings she made or oversaw were very similar to her original watercolors. She also hand-colored some of her engravings.

In 1679, Maria published the first part of her two-part series on caterpillars. The second part came out in 1683. Each book had 50 pictures that Maria engraved and etched. They also had descriptions of the insects, moths, and butterflies she had observed. Her book, Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung – The Caterpillars' Marvellous Transformation and Strange Floral Food, was very popular with some wealthy people because it was written in German. However, scientists at the time mostly ignored her work.

The title page of her 1679 Caterpillars book proudly stated in German:

"wherein by means of an entirely new invention the origin, food and development of caterpillars, worms, butterflies, moths, flies and other such little animals, including times, places and characteristics, for naturalists, artists, and gardeners, are diligently examined, briefly described, painted from nature, engraved in copper and published independently."

Before Maria, Jan Goedart had described and drawn the life stages of European moths and butterflies. But Maria's "invention" was her detailed study of each species, its life cycle, and where it lived. Goedart showed one adult, a pupa, and one larva. Maria showed the differences between male and female adults. She drew wings in different positions and the different colors on each side of the wing. She also showed insects feeding with their long tongues. The first picture in her 1679 Caterpillars book showed the life cycle of the silkworm moth. It started with eggs, then a hatching larva, and several molts of the growing larva. Goedart did not include eggs in his pictures because he believed caterpillars came from water. When Maria published her insect study, many people still believed insects appeared on their own. Maria's discoveries were made independently and supported the findings of other scientists like Francesco Redi.

Maria's pictures of insect life cycles were new and accurate. But her observations on how living things interact are now seen as a major contribution to the modern science of ecology. Her pictures of insects and the plants they eat made her work stand out. Maria was the first to show that each stage of a caterpillar's change into a butterfly depended on a few specific plants for food. She noted that eggs were laid near these plants. In her descriptions, she commented on how the environment affected insect growth. She noted that caterpillars grew bigger each day if they had enough food. "Some then attain their full size in several weeks; others can require up to two months."

Maria made several other unique observations in her detailed studies. She recorded that larvae "many shed their skins completely three or four times." She drew a picture showing a shed exoskeleton. She also described how larvae formed their cocoons. She noted the possible effects of climate on their changes and numbers, how they moved, and that when caterpillars "have no food, they devour each other." Maria recorded this information for specific species.

Studying Nature in Suriname

In 1699, Maria traveled to Dutch Surinam to study and record tropical insects. Going to Suriname for her work was very unusual, especially for a woman. Usually, only men received money from kings or governments to travel to colonies. They would find new plants and animals, collect them, and work there. Scientific trips were not common at this time. Maria's self-funded trip surprised many people. However, she succeeded in finding many new animals and plants in Suriname. Maria spent time studying and classifying her findings. She described them in great detail. She not only described the insects she found but also noted where they lived, what they did, and how local people used them. Her way of classifying butterflies and moths is still useful today. She used Native American names for the plants, which then became used in Europe:

I created the first classification for all the insects which had chrysalises, the daytime butterflies and the nighttime moths. The second classification is that of the maggots, worms, flies, and bees. I retained the indigenous names of the plants, because they were still in use in America by both the locals and the Indians.

Maria's drawings of plants, frogs, snakes, spiders, iguanas, and tropical beetles are still collected today. The German word Vogelspinne (meaning bird spider) likely came from one of Maria's drawings. This drawing, made from sketches in Suriname, shows a large spider that had just caught a bird. In the same drawing and text, Maria was the first European to describe both army ants and leaf cutter ants. She also wrote about how they affected other living things. Maria's pictures of tropical ants were later used and copied by other artists. Her drawings of living things struggling against each other came before Charles Darwin's ideas about the struggle for survival and evolution.

In 1705, three years after returning from her trip, she published Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. Maria paid for the first publication of Metamorphosis herself. She had returned from Suriname with sketches and notes. As word spread among scholars in Amsterdam, visitors came to see her paintings of exotic insects and plants. She wrote, "Now that I had returned to Holland and several nature-lovers had seen my drawings, they pressured me eagerly to have them printed. They were of the opinion that this was the first and most unusual work ever painted in America." With help from her daughters Johanna and Dorothea, Maria put together a series of pictures. This time, she did not make the printing plates herself. She hired three printmakers to do the engraving and watched their work closely. To pay for this, she asked people to subscribe, meaning they would pay her in advance for a special hand-painted edition of the Metamorphosis. Twelve people paid in advance for the expensive hand-painted version. A cheaper printed version in black and white was also published. After her death, the book was reprinted in 1719, 1726, and 1730, reaching more people. It was published in German, Dutch, Latin, and French. Maria thought about publishing the book in English so she could give it to the Queen of England. She thought, "It is reasonable for a woman to make such a gift to a person of the same sex." But this plan never happened.

Metamorphosis and the tropical ants Maria documented were mentioned by scientists like René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur. Maria's Metamorphosis is known for influencing many nature illustrators. Maria also wrote about how the people of Suriname used plants and animals for medicine. For example, she noted that sap from a palm tree was rubbed on itchy scalps to treat worm infections. Maria was also interested in farming. Among the local fruits she showed was the pineapple. When describing the pineapple, Maria mentioned other important books on natural history that had first written about the fruit. While the pineapple had been drawn before, Maria's became the most famous. She provided information on how butterflies and cockroaches affected crops and farming in the colony. While documenting the plants of Suriname, Maria continued to record the metamorphosis of insects. Suriname's insects were shown through their entire life cycle and on the plants they ate.

Many of Maria's paintings that combine a plant, caterpillar, and butterfly are simply decorative. They do not always try to show the correct life cycle. For example, the Gulf fritillary butterfly is shown with a vanilla plant. This is an orchid from the Americas, but it is not the butterfly's host plant. Also, the caterpillar shown is from a different species. This problem appears in many of her illustrations. In a recent edition of her Suriname book, scientists tried to identify the insects and plants. They found that Maria often got the food plants wrong. She also made many mistakes in showing the shapes of the insects. And she usually paired the wrong caterpillar with its adult form. Her drawings are part of how Europeans explored science. Early ways of classifying tropical plants relied on pictures or specimens. After she returned to Amsterdam, her images were used by Carl Linnaeus and others. They used them to identify about a hundred new species. At the time, there was no standard scientific way to name plants and animals. So, Maria used common European words to describe Suriname's animals, like silkworm or wasp. She even called butterflies "summer birds." Linnaeus used Maria's drawings to describe 56 animals and 39 plants from Suriname, including the tarantula, in 1735 and 1753. To refer to her research, Linnaeus shortened her name to Mer.surin. for animals from Suriname and Mer.eur. for European insects.

Maria was the first European woman to go on a scientific trip to South America by herself. In the 19th century, other women like Ida Laura Pfeiffer and Marianne North followed her example. They explored the natural world of Africa. Maria's scientific trip to Suriname happened 100 years before Alexander von Humboldt's famous South America trip. It was also 200 years before Princess Therese of Bavaria's trip. Maria's book about her trip was later seen as a key example of illustrated travel books from Holland in the late 17th century. These books showed an exciting but reachable New World to Europeans.

Scientific Work in Amsterdam

When Maria moved to Amsterdam in 1691, she met several naturalists. Amsterdam was a major center for science, art, and trade during the Dutch Golden Age. When she settled there, Maria found support from the artist Michiel van Musscher. She also took in students, including Rachel Ruysch, whose father was a doctor and professor. Maria became an important person among Amsterdam's botanists, scientists, and collectors. Her Caterpillars books were noticed by the scientific community in England. She continued to raise caterpillars at home. She also went into the countryside around Amsterdam to study ants. Among her friends were the director of the Amsterdam Botanical Garden, Caspar Commelin, the mayor of Amsterdam, Nicolaes Witsen, and the professor of medicine, Fredericus Ruysch.

Trading ships brought back never-before-seen shells, plants, and preserved animals. But Maria was not interested in preserving or just collecting specimens. When she received a specimen from a London pharmacist, she wrote to him. She said she was interested in "the formation, propagation, and metamorphosis of creatures, how one emerges from the other, and the nature of their diet." Still, Maria took on paid work. She helped illustrate the book The Amboinese Curiosity Cabinet by Georg Eberhard Rumpf. Rumpf was a naturalist who had collected Indonesian shells, rocks, fossils, and sea animals for the Dutch East India Company. Maria, and possibly her daughter Dorothea, helped create drawings of the specimens for the book. Rumpf had gone blind and continued working on the book with assistants until 1690. It was published in 1705.

The exotic specimens in Amsterdam might have inspired her trip to Suriname. But this trip only briefly stopped her study of European insects. Maria continued her collecting and observing. She added new pictures to her Caterpillars books and updated old ones. She republished the two books in Dutch in 1713 and 1714 under the title Der Rupsen. She also started studying flies. She rewrote the introduction to her books to remove any mention of insects appearing on their own. She explained that flies came from a caterpillar pupa. She also suggested that flies could be born from waste. The 50 pictures and descriptions of European insects that seemed meant for a third book were published after her death by her daughters. They combined them with the 1713 editions into one large book. Several Metamorphosis editions were also published after her death by her family. They added 12 more pictures. All but two of these seem to have been Maria's work.

A scholar who visited Maria in 1711 described her as lively, hardworking, and polite. Her house was full of drawings, insects, plants, and fruit. Her Suriname watercolors were on the walls. Shortly before Maria's death, her work was seen in Amsterdam by Peter the Great. After she died in 1717, he bought many of her paintings. These are still kept in collections in Saint Petersburg today.

Animals and Plants Named After Maria Sibylla Merian

Long after her death, many animals and plants were named after Maria. Two groups of living things, called genera, were named after her. Three butterflies have been named after her: in 1905, a type of split-banded owlet butterfly Opsiphanes cassina merianae; in 1967, a subspecies of the common postman butterfly Heliconius melpomene meriana; and in 2018, a rare butterfly Catasticta sibyllae from Panamá.

The Cuban sphinx moth is named Erinnyis merianae. A Tessaratomidae bug is named Plisthenes merianae. A group of mantises is named Sibylla. Also, the orchid bee Eulaema meriana.

The bird-eating spider Avicularia merianae was named in her honor because of her research on spiders. The spider Metellina merianae was named after her in 2017. An Argentine tegu lizard is named Salvator merianae. A toad was named Rhinella merianae. A snail was named Coquandiella meriana. The Madagascan population of the African stonechat bird was given the name Saxicola torquatus sibilla.

A group of flowering plants was named Meriania. An iris-like plant was given the name Watsonia meriana.

Maria Sibylla Merian's Legacy Today

In the late 1900s, Maria Merian's work was looked at again. It was recognized as important and reprinted. Her picture was even on the 500 DM banknote before Germany started using the euro. Her portrait also appeared on a 0.40 DM stamp in 1987. Many schools are named after her. In the late 1980s, a record label released new recordings of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's piano music. These featured Maria's flower drawings. She was honored with a Google Doodle on April 2, 2013, for her 366th birthday.

The new interest in her scientific and artistic work came partly from scholars studying her collections. One such collection is in Rosenborg Castle, Copenhagen. In 2005, a modern research vessel called RV Maria S. Merian was launched in Germany. In 2016, Maria's Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium was republished with updated scientific descriptions. In June 2017, a special meeting was held in her honor in Amsterdam. In March 2017, the Lloyd Library and Museum in Cincinnati, Ohio held an exhibition. It showed many of Maria's illustrations as 3D sculptures with preserved insects, plants, and stuffed animals.

The Argentine black and white tegu (Salvator merianae), a large lizard, was named in honor of Maria Merian after it was discovered and classified.

Maria's Daughters' Contributions

Today, Maria Merian is very famous in the art and science worlds. However, some of her work has now been recognized as being done by her daughters, Johanna and Dorothea. For example, one expert has said that 30 out of 91 drawings in the British Museum were actually done by her daughters.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Maria Sibylla Merian para niños

In Spanish: Maria Sibylla Merian para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |