Francesco Redi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francesco Redi

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 18 February 1626 Arezzo, Italy

|

| Died | 1 March 1697 (aged 71) Pisa, Italy

|

| Nationality | Tuscan |

| Alma mater | University of Pisa |

| Known for | Experimental biology Parasitology Criticism of spontaneous generation |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine, entomology, parasitology, linguistics |

| Institutions | Florence |

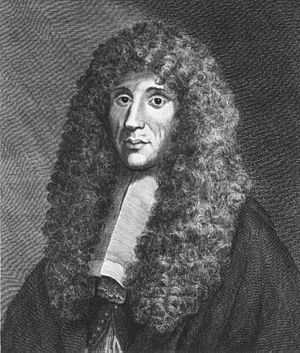

Francesco Redi (born February 18, 1626 – died March 1, 1697) was an Italian doctor, naturalist, biologist, and poet. He is often called the "founder of experimental biology" and the "father of modern parasitology". He was the first person to show that maggots come from flies' eggs, which challenged an old idea called spontaneous generation.

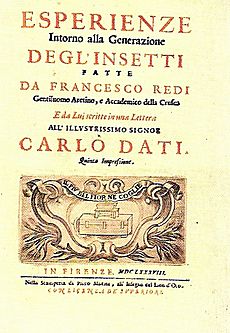

Redi earned his doctor's degrees in medicine and philosophy from the University of Pisa when he was 21. He worked in many Italian cities. He was a smart thinker who questioned common myths. His most famous experiments are in his important book Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl'insetti (Experiments on the Generation of Insects), published in 1668. He proved that vipers do not drink wine or break glasses. He also showed that snake venom is only dangerous when it enters the body through a bite. He correctly observed that snake venoms come from the fangs, not the gallbladder. He was also the first to describe about 180 parasites. He also showed the difference between earthworms and helminths (like tapeworms). He might have been the first to use a "control group" in experiments. This is a basic part of modern biology. His poetry book Bacco in Toscana ("Bacchus in Tuscany") is considered a great work of 17th-century Italian poetry.

Contents

Biography of Francesco Redi

Francesco Redi was born in Arezzo on February 18, 1626. His father, Gregorio Redi, was a well-known doctor in Florence. Francesco studied with the Jesuits. He then went to the University of Pisa. In 1647, at age 21, he earned his doctor's degrees in medicine and philosophy.

He traveled a lot, visiting Rome, Naples, Bologna, Padua, and Venice. In 1648, he settled in Florence. There, he worked for the Medici family, who were very powerful. He was their main doctor and oversaw their medicine supplies. Most of his important scientific work was done here. He became a member of important science groups like the Accademia dei Lincei and the Accademia del Cimento.

Francesco Redi died peacefully in his sleep on March 1, 1697, in Pisa. His body was taken back to Arezzo to be buried.

Redi's Scientific Discoveries

Understanding Snake Venom

In 1664, Redi wrote his first major book, Osservazioni intorno alle vipere (Observations on Vipers). In this book, he started to correct many popular beliefs about vipers. People thought vipers drank wine or that their venom was harmless if swallowed. They also believed a dead viper's head was an antidote. Redi called these "unmasking of the untruths."

He did many experiments on snakebites. He showed that venom was only dangerous when it entered the bloodstream through a bite. He also found that the fang contained the venom as a yellow liquid. He even showed that tying a tight band above a bite could stop the venom from reaching the heart. This work was the start of studying poisons, known as toxicology.

Insects and Life from Non-Living Things

Redi is most famous for his experiments published in 1668. His book, Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl'insetti (Experiments on the Generation of Insects), is considered a very important book in science history. It was one of the first steps to prove wrong the idea of "spontaneous generation." This old theory said that living things could just appear from non-living matter. For example, many people believed that maggots magically grew from rotting meat.

Redi set up a clever experiment. He took six jars and divided them into two groups. In each jar, he put different things like an unknown object, a dead fish, or a piece of raw veal.

- He covered the tops of the first group of three jars with fine gauze. This allowed air to get in but kept flies out.

- He left the other group of three jars completely open.

After several days, he saw maggots only in the open jars. Flies had been able to land on the meat in these jars. No maggots appeared in the gauze-covered jars.

In another experiment, he put meat in three jars:

- One jar was left open. Maggots appeared in this jar because flies could enter.

- One jar was covered with a cork. No maggots appeared inside.

- One jar was covered with gauze. Maggots appeared on the gauze, but they could not get to the meat and did not survive.

Redi continued his work. He collected the maggots and watched them change into flies. He also put dead flies or maggots in sealed jars with dead animals. No new maggots appeared. But when he did the same with living flies, maggots did appear.

Redi was careful to explain his new ideas in a way that did not go against the religious beliefs of his time. He often used ideas from the Bible. His famous saying was: omne vivum ex vivo, which means "All life comes from life."

Studying Parasites

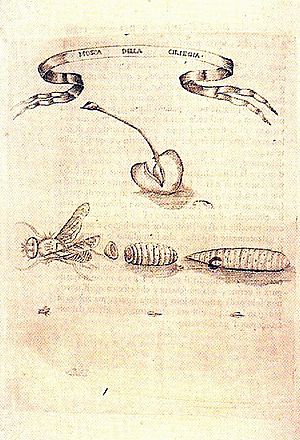

Redi was the first to describe ectoparasites, which are parasites that live on the outside of an animal. He did this in his book Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl'insetti. His book has great drawings of ticks, like deer ticks. It also shows the first picture of the larva of nasal flies that live on deer. He also drew the sheep liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica).

In 1684, he wrote another book called Osservazioni intorno agli animali viventi che si trovano negli animali viventi (Observations on Living Animals, that are in Living Animals). In this book, he described and drew more than 100 different parasites. He also showed the difference between an earthworm and Ascaris lumbricoides, which is a human roundworm.

An important new idea from his book was his experiments with medicines. He used a "control group" in his tests. This is a basic part of how experiments are designed in modern biology. He described about 180 types of parasites. Perhaps his most important discovery was that parasites lay eggs and grow from them. This was different from the popular belief that parasites just appeared on their own.

Redi's Literary Work

Besides being a scientist, Redi was also a poet. He is best known for his poem Bacco in Toscana ("Bacchus in Tuscany"), which came out in 1685. This poem praises Tuscan wines and is still read in Italy today. He was part of two important literary groups: the Academy of Arcadia and the Accademia della Crusca. He helped create the Tuscan dictionary. He also taught the Tuscan language in Florence. He wrote other literary works, including his Letters and Arianna Inferma.

Things Named After Redi

- A crater on Mars is named in his honor.

- A young stage of a parasitic fluke, called "redia," is named after him.

- The Redi Award is a very important award in the study of poisons. It is given in his honor by the International Society on Toxinology.

- A scientific journal from Italy, Redia, is named after him. It was first published in 1903.

- A type of European viper, Vipera aspis francisciredi, is also named after him.

See also

In Spanish: Francesco Redi para niños

In Spanish: Francesco Redi para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |