Käthe Kollwitz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Käthe Kollwitz

|

|

|---|---|

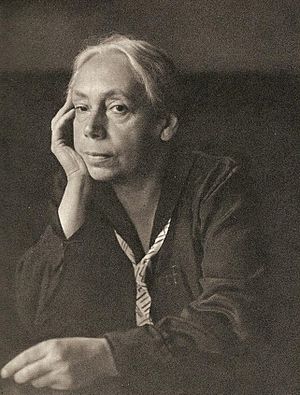

Käthe Kollwitz, 1927

|

|

| Born |

Käthe Schmidt

8 July 1867 |

| Died | 22 April 1945 (aged 77) |

| Resting place | Zentralfriedhof Friedrichsfelde |

| Nationality | German |

| Movement | Expressionism |

| Spouse(s) | Karl Kollwitz |

| Awards | Pour Le Mérite 1929 |

Käthe Kollwitz (born as Schmidt; 8 July 1867 – 22 April 1945) was a famous German artist. She created many different types of art, including painting, printmaking (like etching and woodcuts), and sculpture.

Kollwitz is best known for her art series such as The Weavers and The Peasant War. These works show the difficult lives of working-class people, focusing on the effects of poverty, hunger, and war. Her early art was very realistic, but her later work is often linked to Expressionism, an art style that shows strong feelings. Käthe Kollwitz was also the first woman to be chosen for the Prussian Academy of Arts and to become an honorary professor there.

Life and Art of Käthe Kollwitz

Early Life and Artistic Training

Käthe Kollwitz was born in Königsberg, Prussia, in 1867. She was the fifth child in her family. Her father, Karl Schmidt, was a Social Democrat who worked as a mason and house builder. Her mother, Katherina Schmidt, was the daughter of Julius Rupp, a pastor who started his own church. Käthe's education and art were greatly shaped by her grandfather's ideas about religion and social justice. Her older brother, Conrad, became a well-known economist.

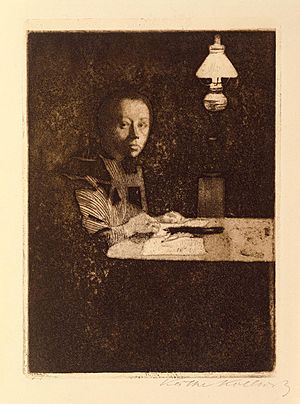

Käthe's father saw her artistic talent. When she was twelve, in 1879, he arranged for her to start drawing lessons. From 1885 to 1886, she formally studied art in Berlin. She learned from Karl Stauffer-Bern, a friend of the artist Max Klinger. At sixteen, she began drawing working people, sailors, and farmers. Klinger's etchings, with their special techniques and focus on social issues, greatly inspired Kollwitz.

In 1888, she studied painting in Munich. There, she realized her main strength was in drawing, not painting. When she was seventeen, her brother Konrad introduced her to Karl Kollwitz, a medical student. Käthe and Karl later got engaged while she was still studying art. In 1890, she returned to Königsberg, opened her first art studio, and continued to draw the hard lives of working people. This theme remained important in her art for many years.

In 1891, Käthe married Karl, who was now a doctor helping the poor in Berlin. They moved into a large apartment that would be Käthe's home until it was destroyed during World War II.

Exploring The Weavers Series

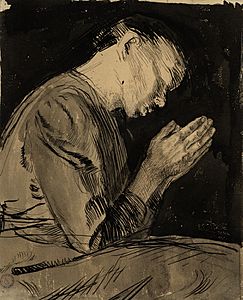

Between the births of her sons, Hans (in 1892) and Peter (in 1896), Kollwitz saw a play called The Weavers by Gerhart Hauptmann. This play showed the difficult lives of weavers in Silesia and their failed uprising in 1844. Kollwitz was deeply moved by the play. She stopped working on another art series and instead created six works about the weavers.

This series included three lithographs (Poverty, Death, and Conspiracy) and three etchings (March of the Weavers, Riot, and The End). Her prints did not just illustrate the play. They showed the workers' sadness, hope, bravery, and their eventual downfall.

The Weavers series was shown to the public in 1898 and received much praise. Adolph Menzel, a famous artist, even nominated her work for a gold medal. However, Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to approve it, saying a medal for a woman would be "going too far." Despite this, The Weavers became Kollwitz's most famous work.

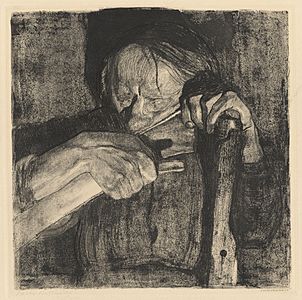

The Peasant War Art Series

Kollwitz's second major art series was Peasant War, which she worked on from 1902 to 1908. This series was inspired by the German Peasants' War, a violent uprising in Southern Germany in 1525. During this time, peasants, who were treated like slaves, fought against their feudal lords and the church.

Kollwitz had been interested in this topic since she was young. She and her brother Konrad used to pretend to be revolutionaries. Kollwitz was a strong supporter of people who didn't have a voice, and she liked to show the working class in a unique way.

While working on Peasant War, Kollwitz visited Paris twice. In 1904, she took classes at the Académie Julian to learn sculpture. Her etching Outbreak won the Villa Romana prize, which allowed her to stay in a studio in Florence for a year in 1907. Even though she didn't create new art there, she later remembered how much the early Renaissance art in Florence influenced her.

Art During Modernism and World War I

After returning to Germany, Kollwitz continued to show her art. She was impressed by younger artists, especially those from the Expressionist and Bauhaus movements. These artists inspired her to make her own art simpler. Later works like Runover (1910) and Self-Portrait (1912) show this new style. She also continued to create sculptures.

In October 1914, Kollwitz's younger son, Peter, died fighting in World War I. This loss caused a long period of sadness for her. By the end of 1914, she had started drawing ideas for a monument to Peter and other fallen soldiers. She destroyed her first attempt in 1919 and began again in 1925. The memorial, called The Grieving Parents, was finished in 1932. It was placed in the Belgian cemetery of Roggevelde. Later, when Peter's grave was moved to the Vladslo German war cemetery, the statues were moved there too.

In 1917, on her 50th birthday, Paul Cassirer's galleries held a special exhibition of 150 of Kollwitz's drawings.

Kollwitz was a strong believer in socialism and pacifism, and she later became interested in communism. She showed her political beliefs in her woodcut print, "Memorial Sheet for Karl Liebknecht". She also joined the Arbeitsrat für Kunst, a group connected to the Social Democratic government after the war.

While working on the Liebknecht print, she found that etching wasn't strong enough for her big ideas. After seeing woodcuts by Ernst Barlach, she decided to use woodcut for the Liebknecht print. By 1926, she had made about 30 woodcuts.

In 1919, Kollwitz became a professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts. She was the first woman to hold this position. This job gave her a regular income, a large studio, and a full professorship. However, the Nazi government forced her to resign from this position in 1933. In 1928, she was also made director of the Master Class for Graphic Arts at the Prussian Academy, but this title was also taken away when the Nazi regime came to power.

The War (Krieg) Series

After World War I, Kollwitz continued to express her feelings about the war through her art. From 1922 to 1923, she created the War series using woodcuts. This series included works like The Sacrifice, The Volunteers, The Parents, The Widow I, The Widow II, The Mothers, and The People. Much of this art was a response to pro-war messages. Kollwitz and artist Otto Dix used these ideas to create anti-war art. Kollwitz wanted to show the terrible realities of war to fight against the growing support for war in Germany. In 1924, she finished three of her most famous posters: Germany's Children Starving, Bread, and Never Again War.

The Death Cycle

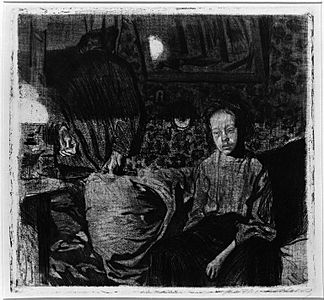

In the mid-1930s, working in a smaller studio, Kollwitz completed her last major series of lithographs, called Death. This series included eight prints: Woman Welcoming Death, Death with Girl in Lap, Death Reaches for a Group of Children, Death Struggles with a Woman, Death on the Highway, Death as a Friend, Death in the Water, and The Call of Death.

Seed Corn Must Not Be Ground (1942)

In 1918, during World War I, a writer named Richard Dehmel asked for more young soldiers to fight. Kollwitz wrote a strong letter to the newspaper, saying there should be no more war. She used the phrase "seed corn must not be ground" to refer to young soldiers dying in the war. In 1942, she created an artwork with the same name, this time in response to World War II. The artwork shows a mother protecting three young children with her arms.

Later Life and World War II

In 1933, after the National-Socialist regime came to power, Nazi authorities forced Kollwitz to leave her position at the Akademie der Künste. This happened because she supported a public appeal against the Nazis. Her art was also removed from museums. Even though she was banned from showing her work, the Nazis used one of her "mother and child" pieces for their own propaganda.

In July 1936, the Gestapo (Nazi secret police) visited her and her husband. They threatened her with arrest and being sent to a Nazi concentration camp. However, Kollwitz was well-known internationally, so no further action was taken against her.

On her 70th birthday, she received over 150 telegrams from important people in the art world. She also received offers to live in the United States, but she refused. She was worried that leaving Germany might cause problems for her family.

Käthe Kollwitz lived longer than her husband, who died from an illness in 1940. She also outlived her grandson Peter, who died in action during World War II two years later.

In 1943, she had to leave Berlin because of bombings. Her house was bombed later that year, and many of her drawings, prints, and documents were lost. She moved first to Nordhausen, then to Moritzburg, a town near Dresden. She spent her last months there as a guest of Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony. Käthe Kollwitz died on April 22, 1945, just 16 days before World War II ended in Europe.

Käthe Kollwitz's Legacy

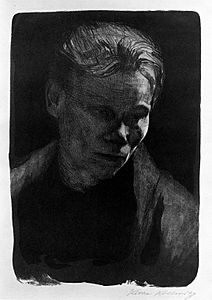

Kollwitz created a total of 275 prints using etching, woodcut, and lithography. Almost all the portraits she made were of herself, with at least fifty self-portraits. These self-portraits show an honest look at herself throughout her life. They are like "psychological milestones" of her journey.

After her death, the dance school of Mary Wigman created a dance called Dances for Käthe Kollwitz, which was performed in Dresden in 1946. Käthe Kollwitz is also a character in William T. Vollmann's book Europe Central, which won an award in 2005. The book describes the lives of people affected by World War II in Germany and the Soviet Union. Kollwitz's chapter is named "Woman with Dead Child," after her sculpture.

An enlarged version of a similar Kollwitz sculpture, Mother with her Dead Son, was placed in 1993 in the center of Neue Wache in Berlin. This sculpture now serves as a memorial to "the Victims of War and Tyranny."

More than 40 schools in Germany are named after Kollwitz. A statue of Kollwitz by Gustav Seitz was put up in Kollwitzplatz, Berlin, in 1960, where it still stands today.

Four museums are dedicated only to her work: in Berlin, Cologne, Moritzburg, and Koekelare. The Käthe Kollwitz Prize, started in 1960, is also named after her.

In 1986, a DEFA film called Käthe Kollwitz was made about the artist, with Jutta Wachowiak playing Kollwitz. She is also one of the 14 main characters in the 2014 series 14 - Diaries of the Great War. In 2017, Google Doodle celebrated Kollwitz's 150th birthday.

An exhibition called Portrait of the Artist: Käthe Kollwitz was held in Birmingham, England, in 2017. It was planned to be shown in other cities as well.

Images for kids

-

Bust of a Working Woman in a Blue Shawl, 1903. Brooklyn Museum

-

The Young Couple, 1904. Brooklyn Museum

-

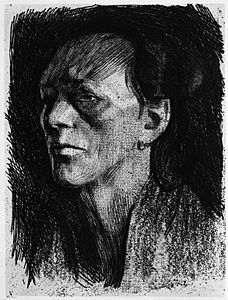

Working Woman (with Earring), 1910. Brooklyn Museum

-

Die Mütter [The Mothers], 1922, woodcut, Library of Congress

See also

In Spanish: Käthe Kollwitz para niños

In Spanish: Käthe Kollwitz para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |