Hannah Höch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hannah Höch

|

|

|---|---|

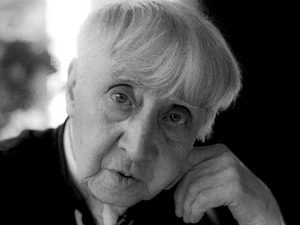

Hannah Höch self-portrait, c.1926

|

|

| Born |

Anna Therese Johanne Höch

1 November 1889 |

| Died | 31 May 1978 (aged 88) |

| Education | Berlin College of Arts and Crafts, The School of the Royal Museum of Applied Arts |

| Known for | Collage |

|

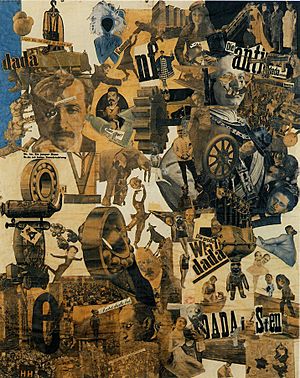

Notable work

|

Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919 |

| Movement | Dada |

Hannah Höch (born November 1, 1889 – died May 31, 1978) was a famous German artist. She was part of an art movement called Dada. Hannah Höch is especially known for her art from the Weimar Republic period. During this time, she helped invent a special type of art called photomontage.

Photomontage is a kind of collage. In photomontage, artists use actual photographs or pictures from newspapers and magazines. They cut these images out and paste them together to create a new picture.

Hannah Höch's art often explored ideas about the "New Woman". This was a popular idea at the time about women who were energetic and professional. They were seen as ready to be equal to men. Höch was interested in how these ideas were formed and who decided what women's roles should be.

Her artworks also looked at themes like androgyny (combining male and female traits). She also explored political ideas and changing gender roles. These themes helped create a feminist message in her art. This message encouraged freedom and power for women. It was important during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and still is today.

Contents

About Hannah Höch's Life

Hannah Höch was born Anna Therese Johanne Höch in Gotha, Germany. She went to school, but her family expected her to help at home. In 1904, she left school to care for her younger sister, Marianne.

In 1912, she started art classes in Berlin. She studied glass design and graphic arts. She chose these subjects to please her father, instead of fine arts.

When World War I began in 1914, she left school. She went home to Gotha to work with the Red Cross. In 1915, she returned to Berlin. There, she joined a graphics class at the Museum of Arts and Crafts.

Joining the Dada Movement

In 1915, Hannah Höch met Raoul Hausmann. He was a member of the Berlin Dada art movement. Höch became deeply involved with the Berlin Dadaists in 1917. She was the only woman in the Berlin Dada group.

She was known for being independent and for her unique style. She often explored themes of the "New Woman" in her art. This was about women who were free to vote and financially independent.

From 1916 to 1926, Höch worked for a publisher called Ullstein Verlag. She designed patterns for dresses, embroidery, and lace. These designs appeared in women's magazines like Die Dame. You can see the influence of this work in her collages. She often used sewing patterns and needlework designs in her art.

From 1926 to 1929, she lived and worked in the Netherlands. Hannah Höch made many important friends and connections. These included artists like Kurt Schwitters, Theo van Doesburg, and Piet Mondrian. Höch, along with Raoul Hausmann, was one of the first artists to create photomontage.

Later Years and Challenges

Hannah Höch stayed in Berlin during the Third Reich (Nazi Germany). She tried to keep a low profile. She was the last member of the Berlin Dada group to remain in Germany. She bought a small garden house in Berlin-Heiligensee, a quiet area.

She married businessman Kurt Matthies in 1938, but they divorced in 1944. Her art was considered "degenerate art" by the Nazis. This made it very hard for her to show her work.

After the war, her art was not as famous as it had been before. However, she continued to create photomontages. She exhibited her work around the world until she passed away in 1978 in Berlin. Her house and garden can be visited during the annual Tag des offenen Denkmals (Open Monument Day).

On November 1, 2017, her 128th birthday was celebrated with a Google Doodle.

Understanding the Dada Art Movement

Dada was an art movement that started in 1916 in Zurich, Switzerland. The artists in this movement rejected traditional ideas. They were against monarchy, militarism, and old-fashioned ways of thinking. Dada was known for its "anti-art" feeling.

Dada artists believed that art should have no rules or limits. They thought art could be silly and playful. These ideas came after World War I. The war made people question governments and reject military actions. Many Dada artworks criticized the Weimar Republic. This was Germany's attempt to create a democracy after World War I.

The Dada movement often showed a negative view of society. The word "dada" itself has no real meaning. It's a childlike word that shows the lack of logic in much of their art. Key artists in the movement included George Grosz, John Heartfield, and Raoul Hausmann.

Some people believe Hannah Höch was accepted into the Dada group because of her relationship with Hausmann. George Grosz and John Heartfield initially didn't want Höch to show her art at the First International Dada Fair in 1920. Raoul Hausmann had to argue for her to be included. Even then, Hausmann later tried to say she was "never a member of the club." Despite this, she was known as "Dadasophin" within the movement.

Hannah Höch's Photomontages

Hannah Höch is most famous for her photomontages. These collages used images from popular culture. She would cut up and reassemble pictures. This style fit well with the Dada ideas. However, some male Dadaists were hesitant to fully accept her work due to sexism.

Her art added a unique feminist touch to Dada's ideas. She criticized society, but her identity as a woman and her feminist themes meant she was never fully accepted by the male Dadaists.

Like other Dada artists, Höch's work was also examined closely by the Nazis. They considered it "degenerate." The Nazis stopped her planned exhibition at the Bauhaus art school in 1932. They disliked her art style, her political messages, and the fact that she was a woman artist.

Nazi ideas preferred art that showed the "ideal" German man and woman. Höch's images often challenged this view. The Nazis wanted clear, traditional art that didn't require deep thought. They felt Dada's chaotic style was unhealthy. Höch went into hiding during the Nazi years. She was able to return to the art world after the Nazis were defeated.

Photomontages by Höch showed the busy visual world of Berlin from a woman's point of view. She was one of the few prominent female artists in the early 20th century. She was almost unique as a woman active in the Dada movement. She also actively promoted the idea of women working creatively in society. Her pioneering photomontage art directly addressed gender and the role of women in modern society.

In her montages, Höch collected images and text from newspapers and magazines. She combined them in surprising ways. This allowed her to express her views on important social issues. The fact that she used images from current media made her messages feel very real.

The power of her art came from intentionally cutting up and rebuilding images. This suggested that current issues could be seen in different ways. This technique was first seen as very rebellious. But by the 1930s, it became an accepted design style. It showed that mass culture and fine art could be combined in a meaningful way. The unclear meanings in her work were key to how she discussed gender. These complex ways of showing gender allowed women to embrace both their masculine and feminine sides. This led to a stronger sense of being an individual. Photomontage is a big part of Hannah Höch's artistic legacy.

Women in Dada: A Closer Look

While some Dadaists talked about women's freedom, they were often unwilling to include women in their group. Hans Richter once joked that Höch's main contribution was providing "sandwiches, beer and coffee." Raoul Hausmann even suggested Höch get a job to support him, even though she was the only one in their group with a steady income.

Hannah Höch was the only woman in the Berlin Dada group. Other important, but often overlooked, Dada women included Sophie Taeuber and Beatrice Wood. Höch showed the unfairness of the Berlin Dada group and German society in her photomontage, Da-Dandy.

She also wrote about the hypocrisy of men in the Dada movement. In her 1920 essay "The Painter," she described a modern couple who believed in gender equality. This was a new and surprising idea for the time. This shows how Höch used different art forms to share her social ideas.

Höch's work at Ullstein Verlag, designing for women's magazines, made her aware of the difference between how women were shown in media and their real lives. Her workplace gave her many images for her art. She also criticized marriage. She often showed brides as mannequins or children. This reflected the idea that women were incomplete and had little control over their lives.

Höch worked for the magazine Ullstein Verlag from 1916 to 1926. She was in the department for design patterns, handicrafts, knitting, and embroidery. These were considered "women's" art forms. Her pattern designs and early modern art experiments were connected. They blurred the lines between traditionally male and female art. In 1918, she wrote a "Manifesto of Modern Embroidery." It encouraged modern women to be proud of their work. She used her experience and collected advertising materials to create images that showed how society "constructs" women.

Höch saw herself as part of the women's movement in the 1920s. This is clear in her artwork Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser DADA durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands (1919–20). Her pieces often combined male and female features into one being. During the Weimar Republic, "mannish women" were both celebrated and criticized for breaking traditional gender roles. In this artwork, Höch compared her scissors, used for cutting images, to a kitchen knife. This symbolized cutting through the male-dominated world of politics and public life in Weimar culture.

Key Artworks by Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch was a pioneer of photomontage and the Dada movement. Many of her artworks cleverly criticized the beauty industry of her time. This industry was growing fast through fashion and advertising photography. Many of her political works from the Dada period linked women's freedom with social and political change.

Her art showed the busy visual world of Berlin from a woman's perspective. Her photomontages often criticized the "Weimar New Woman." She created these by combining images from magazines. Her works from 1926 to 1935 often showed same-sex couples. Women became a main theme in her art again from 1963 to 1973. She also used traditional feminine art forms like embroidery and lace in her collages. This helped highlight ideas about gender.

Höch also made strong statements about racial discrimination. Her most famous piece is Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser DADA durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands. This means "Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany." It was a criticism of Weimar Germany in 1919. This artwork combines newspaper images from the time. They are mixed and remade to create a new statement about life and art in the Dada movement.

From an Ethnographic Museum (1929) was one of Höch's most important projects. It has twenty photomontages. These show images of European women's bodies mixed with images of African men's bodies and masks from museum catalogs. This creates collages that show different cultures as interchangeable. A stylish European woman looks just as fashionable next to African tribal objects. Also, the non-Western artifact still seems like a ritual object even when mixed with European features. Höch also created Dada Puppens (Dada Dolls) in 1916. These dolls were inspired by Hugo Ball, a Dada founder from Zurich. The doll's costumes looked like the geometric shapes of Ball's own costumes.

Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919)

The Dada movement was very political. Dada artists often used satire to talk about the issues of their time. They pushed art to its limits to show the chaos in Germany after World War I. Many of Höch's political photomontages made fun of the new republic's pretend socialism. They also connected women's freedom with political revolution.

Perhaps Höch's most famous artwork, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Beer-Belly of the Weimar Republic, symbolizes her cutting through the male-dominated society. The piece directly criticizes the failed democracy of the Weimar Republic. Cut with the Kitchen Knife is a powerful mix of cut-up images. It was displayed right in the middle of the famous First International Dada Fair in 1920. This photomontage combines pictures of political leaders with sports stars, city images, and Dada artists.

The Beautiful Girl (1920)

The "New Woman" in Weimar Germany was a symbol of modern times and freedom. Women in Weimar Germany theoretically had new freedom to define themselves socially, politically, and personally. Hannah Höch explored all these areas. However, women still faced many challenges with their jobs and money. They were given more freedom, but it often seemed to be decided for them. They were still limited to certain jobs and had fewer benefits than men.

Looking at Höch's piece Beautiful Woman shows how the idea of the "New Woman" was created. The artwork combines images of the ideal feminine woman with car parts. In the top right corner, there is a woman's face with cat eyes. With industrialization, women had more chances to work. While this was exciting, it was also scary. The cat eyes staring down at the image symbolize this fear. This image shows that even though women were excited about the "New Woman" and the freedom it might bring, this freedom was still shaped by men, who held most of the power.

Ethnographic Museum Series (1924–1930)

Höch created a large series of artworks called the Ethnographic Museum Series. She started this after visiting an ethnographic museum. Germany had started to expand into African and Oceanic lands by the 1880s. This brought many cultural artifacts into Germany. Höch was inspired by the masks and displays in the museums. She began to use them in her art.

Mother (1930)

This piece is a photomontage from Höch's Ethnographic Museum Series. It mainly uses a photo of a pregnant, working-class mother. Höch covers the woman's face with a mask from the Kwakwakaʼwakw (Kwakuti Indian tribe) from the Northwest Coast.

Strange Beauty II (1966)

Höch returned to focusing on the female figure in the 1960s. Before this, she had explored surrealism and abstraction. Strange Beauty II is part of this return. It shows a woman surrounded by feathery pink plants. The woman's face is covered by a Peruvian terracotta trophy head. In this artwork, Höch replaces the "New Woman" figure's head with a tribal mask.

Exhibitions of Hannah Höch's Work

Hannah Höch's art has been shown around the world in both solo and group exhibitions.

The Whitechapel Gallery in London held a major exhibition of her work from January 15 to March 23, 2014. This show included over one hundred artworks from different collections. These pieces were created by Höch from the 1910s to the 1970s. Important works included Staatshäupter (Heads of State) (1918–20) and many works from the From an Ethnographic Museum series.

Selected Solo Exhibitions

- 2017: Hannah Höch – Auf der Suche nach der versteckten Schönheit (Looking for the hidden beauty), Galerie und Verlag St. Gertrude, Hamburg.

- 2016: Hannah Höch – Revolutionärin der Kunst (Revolutionary of Art), Kunsthalle Mannheim and Kunstmuseum Mülheim an der Ruhr.

- 2015: Vorhang auf für Hannah Höch (Curtain up for Hannah Höch), Kunsthaus Stade, Stade, Germany.

- 2014: Hannah Höch, Whitechapel Gallery, London.

- 2008: Hannah Höch – Aller Anfang ist DADA (Every Beginning is DADA), Museum Tinguely, Basel.

- 2007: Hannah Höch – Aller Anfang ist DADA (Every Beginning is DADA), Berlinische Galerie, Berlin.

- 1997: The Photomontages of Hannah Höch, Walker Art Center, Museum of Modern Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Minneapolis, New York City, Los Angeles.

- 1993: Hannah Höch, Museums of the City of Gotha, Germany.

- 1974: Hannah Höch, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto.

- 1961: Hannah Höch: Bilder, Collagen, Aquarelle 1918–1961, Galerie Nierendorf, Berlin.

- 1929: Hannah Höch, Kunstzaal De Bron, The Hague.

See also

In Spanish: Hannah Höch para niños

In Spanish: Hannah Höch para niños

- Marcel Duchamp

- List of German women artists