John Heartfield facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Heartfield

|

|

|---|---|

John Heartfield in 1959

|

|

| Born |

Helmut Herzfeld

19 June 1891 Berlin-Schmargendorf, Berlin, German Empire

|

| Died | 26 April 1968 (aged 76) |

| Nationality | German, East German |

| Alma mater | Royal Bavarian Arts and Crafts School |

| Known for | Photomontage |

John Heartfield (born Helmut Herzfeld; 19 June 1891 – 26 April 1968) was a German artist from the 1900s. He was a pioneer in using art to make strong political statements. Many of his famous photomontages spoke out against the Nazis and fascism. Heartfield also designed covers for books by authors like Upton Sinclair. He created stage sets for famous playwrights such as Bertolt Brecht.

Contents

About John Heartfield's Life

Early Life and Art Education

John Heartfield was born Helmut Herzfeld on 19 June 1891. His birthplace was Berlin-Schmargendorf, in the German Empire. His father, Franz Herzfeld, was a writer who believed in socialism. His mother, Alice, worked with textiles and was also a political activist.

In 1899, Helmut and his siblings, Wieland, Lotte, and Hertha, faced a difficult time. Their parents left them in the woods after Franz Herzfeld was accused of something serious. The family had to leave Germany and went to Switzerland. Later, they were sent to Austria. The four children then went to live with their uncle, Ignaz, in a small town called Aigen.

In 1908, Heartfield began studying art in Munich. He attended the Royal Bavarian Arts and Crafts School. Two commercial designers, Albert Weisgerber and Ludwig Hohlwein, influenced his early work.

While living in Berlin, he changed his name to "John Heartfield." This was an anglicisation of his German name, Helmut Herzfeld. He did this to protest against strong anti-British feelings in Germany during World War I. People in Berlin often shouted "May God punish England!" at that time.

In 1916, Heartfield and his friend George Grosz started experimenting with pasting pictures together. This new art form was later called photomontage. It became a very important part of their artwork.

In 1917, Heartfield joined the Berlin Club Dada. He became very active in the Dada art movement. He helped organize the first international Dada fair in Berlin in 1920. Dada artists liked to challenge traditional art. They often made fun of public art events and called traditional art boring.

In January 1918, Heartfield joined the German Communist Party (KPD). This was a new political group at the time.

Art and Politics Between the Wars

In 1919, Heartfield was removed from his job in the German army's film service. This happened because he supported a strike. The strike followed the deaths of political leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. With George Grosz, he started a funny magazine called Die Pleite.

Heartfield met the famous writer Bertolt Brecht in 1924. He became part of a group of German artists. This group included Brecht, Erwin Piscator, and Hannah Höch.

Even though he designed many stage sets and book covers, photomontage was Heartfield's main art form. He created the first political photomontages. He mostly worked for two publications. One was the daily newspaper Die Rote Fahne ("The Red Flag"). The other was the weekly communist magazine Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIZ). This magazine published his most famous works. He also designed theater sets for Erwin Piscator and Bertolt Brecht.

During the 1920s, Heartfield made many photomontages. Many of these were used as covers for books. An example is his design for Upton Sinclair's book The Millennium.

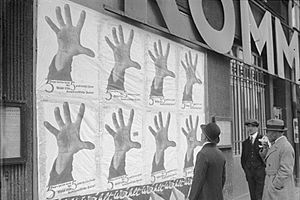

His posters were printed using a special method called rotogravure. This allowed his montages to be seen on the streets of Berlin. This happened between 1932 and 1933, just as the Nazis were gaining power.

His political montages often appeared on the cover of Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung. This was from 1930 to 1938. It was a very popular weekly magazine. At its peak, it sold up to 500,000 copies. This meant many people saw Heartfield's artwork at newsstands.

Heartfield lived in Berlin until April 1933. This was when the Nazi Party took control of Germany. On Good Friday, members of the SS broke into his apartment. He escaped by jumping from his balcony and hiding in a trash bin. He then fled Germany. He walked over the Sudeten Mountains to Czechoslovakia. He eventually became one of the top five people on the Gestapo's most-wanted list.

In 1934, he created a powerful image. It showed four bloody axes tied together to form a swastika. This mocked the Nazi motto "Blood and Iron." This image was published in AIZ in Prague.

In 1938, Germany was about to take over Czechoslovakia. Heartfield had to escape from the Nazis again. He moved to England. There, he was held as an "enemy alien" for a short time. His health started to get worse. He later lived in Hampstead, London. His brother Wieland was not allowed to stay in Britain. So, Wieland and his family moved to the United States in 1939.

Life After World War II

After World War II, Heartfield wanted to stay in England. But his requests were denied. In 1950, he was convinced to join his brother Wieland. Wieland was living in East Berlin, East Germany. Heartfield moved into an apartment next to his brother's.

However, the East German government was suspicious of him. This was because he had lived in England for 11 years. He was questioned but was not put on trial. Still, he was not allowed to join the East German Academy of the Arts. He was also forbidden from working as an artist for a while. He was even denied health benefits.

Thanks to the help of Bertolt Brecht and Stefan Heym, Heartfield was finally accepted into the Academy of the Arts in 1956. After this, he created some montages that warned about the danger of nuclear war. But he never made as much art as he did when he was younger.

In East Berlin, Heartfield worked closely with theater directors. These included Benno Besson and Wolfgang Langhoff. He created new and interesting stage designs for Bertolt Brecht. Heartfield used simple props and plain stages. This helped Brecht's plays involve the audience more.

In 1967, he visited Britain. He started planning a show of his artwork. His wife, Gertrud, and the Berlin Academy of Arts finished the show after he passed away. It was shown in London in 1969.

John Heartfield's Famous Works

Heartfield is best known for the 240 political photomontages he made from 1930 to 1938. Most of these artworks strongly criticized fascism and Nazism. His photomontages often made fun of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. He would change Nazi symbols like the swastika to weaken their message.

Examples of His Art

- Adolf, the Superman (published in Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung [AIZ], Berlin, 17 July 1932). This artwork used a special X-ray effect. It showed gold coins in Adolf Hitler's throat and stomach. This happened as he was yelling about Germany's enemies.

- In Göring: The Executioner of the Third Reich (AIZ, Prague, 14 September 1933), Hermann Göring is shown as a butcher. This image criticized his actions.

- The Meaning of Geneva, Where Capital Lives, There Can Be No Peace (AIZ, Berlin, 27 November 1932). This piece shows a peace dove stuck on a bloody knife. It is in front of the League of Nations. The cross on the Swiss flag is changed into a swastika.

- Hurrah, die Butter ist Alle! (Hurray, There's No Butter Left!) was on the front page of AIZ in 1935. This photomontage made fun of propaganda. It shows a German family eating a bicycle at dinner. A picture of Hitler hangs on the wall. The wallpaper has swastikas on it. A baby chews on an axe with a swastika. A dog licks a large nut and bolt. The title includes a quote from Hermann Göring during a food shortage. He once said, "Iron ore has made the Reich strong. Butter and drippings have, at most, made the people fat."

Death and Lasting Impact

John Heartfield had health problems throughout his life. He passed away on 26 April 1968 in East Berlin, East Germany. He was buried in the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery, near where Bertolt Brecht used to live.

After his wife, Gertrud Heartfield, died, the East German Academy of the Arts received all of his remaining artworks. When the West German Academy of Arts later joined with the East German Academy, Heartfield's collection moved with it.

From April 15 to July 6, 1993, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City held a show of Heartfield's original montages.

In 2005, the British Tate Gallery showed his photomontage pieces. The Museum Ludwig in Cologne also had a show of his work in 2008.

See also

In Spanish: John Heartfield para niños

In Spanish: John Heartfield para niños