Kurt Schwitters facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kurt Schwitters

|

|

|---|---|

Kurt Schwitters, London 1944

|

|

| Born |

Kurt Hermann Eduard Karl Julius Schwitters

20 June 1887 Hanover, Germany

|

| Died | 8 January 1948 (aged 60) Kendal, England

|

| Education | Dresden Academy |

| Known for | Dancing, collage, artist's book, installation, sculpture, poetry |

|

Notable work

|

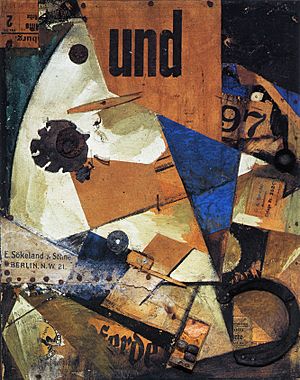

Das Undbild, 1919 |

| Movement | Merz |

Kurt Schwitters (born June 20, 1887 – died January 8, 1948) was a German artist. He was born in Hanover, Germany. Schwitters was a very creative person who worked in many different art forms. These included dadaism, constructivism, surrealism, poetry, and painting. He also created sculptures, graphic design, and typography. He is most famous for his unique collages, which he called Merz Pictures.

Contents

Early Life and the Start of Merz Art (1887–1922)

Growing Up in Hanover

Kurt Schwitters was born in Hanover, Germany, on June 20, 1887. He was the only child of Eduard and Henriette Schwitters. His father used to own a ladies' clothing shop. After selling the shop, his family bought properties in Hanover. They rented these out, which provided them with a steady income.

In 1901, Kurt had his first epileptic seizure. This health condition later meant he didn't have to serve in the military during World War I. He studied art at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts from 1909 to 1915. After his studies, he returned to Hanover and began his art career. His early paintings were in a style called post-impressionist.

As World War I continued, his art became darker. It slowly developed into a unique expressionist style. During the last year and a half of the war, he worked as a drafter in a factory. This experience influenced his later art. He started to show machines as symbols of human life.

Kurt married his cousin, Helma Fischer, in 1915. Their first son died shortly after birth. Their second son, Ernst, was born in 1918. Ernst stayed very close to his father throughout his life. They even went into exile together in Britain. In 1918, Germany's situation after World War I greatly changed his art.

Joining the Avant-Garde with Der Sturm

In 1918, Schwitters met Herwarth Walden after showing his expressionist paintings. He displayed two semi-abstract landscapes at Walden's gallery, Der Sturm, in Berlin. This led him to meet important artists in the Berlin Avant-garde movement. These artists included Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, and Jean Arp.

Even though Schwitters continued to paint in an expressionist style, he also started creating abstract collages. These were influenced by Jean Arp's work. He called his new art style Merz. The name came from a piece of text he found in his work Das Merzbild. The text was from "Commerz Und Privatbank" (commerce and private bank).

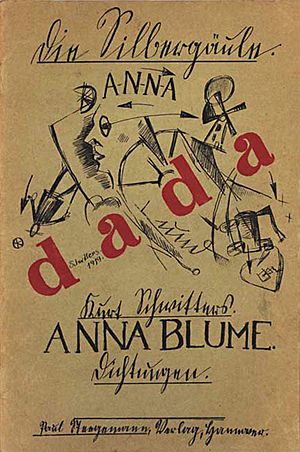

By late 1919, Schwitters became a well-known artist. He had his first solo exhibition at Der Sturm gallery. He also published his famous poem An Anna Blume. This was a playful, non-sensical love poem.

Dada and Merz Art

Schwitters wanted to join the Berlin Dada group. However, some members like Richard Huelsenbeck didn't want him to join. They thought his art was too romantic. Despite this, Schwitters used many Dada ideas in his own art. He even used the word "Dada" on the cover of his poem An Anna Blume.

He later performed Dada recitals across Europe. He did this with artists like Theo van Doesburg, Tristan Tzara, Jean Arp, and Raoul Hausmann. His art was often more like Zürich Dada, which focused on performance and abstract art. This was different from Berlin Dada's more political approach.

In 1922, Theo van Doesburg organized Dada performances in the Netherlands. Schwitters joined these events, performing in cities like Amsterdam and Utrecht. He also gave solo performances. He often visited Drachten, Friesland, staying with local painter Thijs Rinsema. They even made collages together. Schwitters also worked with an intarsia worker. This led to new works where collage techniques were used with wood.

Merz art has been called 'Psychological Collage'. Schwitters used pieces of found objects to create meaningful art. These objects often hinted at current events. For example, Merzpicture 29a, Picture with Turning Wheel (1920) used wheels that only turned clockwise. This hinted at Germany's political shift to the right.

His collages often included personal items. These were things like bus tickets or small gifts from friends. Later, his collages featured images from popular media. For instance, En Morn (1947) included a picture of a blonde girl. This was similar to later pop art. Many artists, like Robert Rauschenberg, were influenced by Schwitters's work.

Merz art was not just collages. It also included art periodicals, sculptures, sound poems, and installations. Schwitters used the term "Merz" for many years. However, after 1931, the word "Merz" rarely appeared in the titles of his works.

International Art and Merz Magazine (1922–1937)

The Merz Periodical

As Germany's political situation became more stable, Schwitters's art changed. It was less influenced by Cubism and Expressionism. He started to give lectures and perform with other international artists. He toured countries like Czechoslovakia and the Netherlands.

Schwitters published a magazine called Merz from 1923 to 1932. Each issue focused on a different theme. For example, Merz 5 (1923) featured prints by Jean Arp. Merz 8/9 (1924) was designed by El Lissitzky. Merz 14/15 (1925) was a children's story by Schwitters and others. The last issue, Merz 24 (1932), was the full text of his famous sound poem, Ursonate.

His art during this time became more Modernist. It had a cleaner style, similar to works by Jean Arp and Piet Mondrian. His friendship with El Lissitzky was very important. His Merz pictures from this period show the influence of Constructivism.

Schwitters's art was often shown in the U.S. thanks to his friend Katherine Dreier. In the late 1920s, he became a well-known typographer. He designed catalogs and worked for advertising agencies. He also became the official typographer for Hanover city council. Many of his designs appeared in his Merz pictures. He even experimented with creating a new alphabet. In the late 1920s, Schwitters joined the Deutscher Werkbund, a German design group.

The Merzbau Art Installation

Besides his collages, Schwitters also transformed the insides of several rooms. The most famous was the Merzbau. This was a huge art installation in his family home in Hanover. He started working on it around 1923. The first room was finished in 1933. He kept adding to it until he had to leave Germany in 1937.

Most of the house was rented out, so the Merzbau didn't take up the whole house. By 1937, it had spread to two rooms, a balcony, and parts of the attic and cellar. Sadly, it was destroyed in a bombing raid in 1943.

Early photos show the Merzbau looking like a cave. It had columns and sculptures. It included works by other Dada artists like Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann. By 1933, it had become a large sculptural space. Photos from that year show angled surfaces sticking out into a white room. The word 'Merzbau' was first used in 1933.

The Sprengel Museum in Hanover has a recreation of the first room of the Merzbau.

Schwitters later started a similar installation in Norway. It was in the garden of his house near Oslo. This was almost finished when he left Norway in 1940. It burned down in 1951. His last Merzbau was in Elterwater, England. It was not finished when he died in 1948. Another living space he created can still be seen on the island of Hjertøya in Norway. This is sometimes called a fourth Merzbau. Its interior has been moved and will be shown in the Romsdal Museum.

The Ursonate Sound Poem

Schwitters created and performed an early example of sound poetry called Ursonate. This means Original Sonata. He worked on it from 1922 to 1932. The poem was inspired by Raoul Hausmann's poem "fmsbw". Schwitters first performed Ursonate in 1925. He performed it often, making changes and adding to it. He published his notes for the performance in the last Merz magazine in 1932. He continued to work on it for another ten years.

Life in Exile (1937–1948)

Escape to Norway

As the Nazis gained power in Germany, Schwitters's art was labeled "Entartete Kunst". This meant it was considered bad or harmful. His work was shown in touring exhibitions organized by the Nazi party. He lost his job with the Hanover City Council in 1934. His art in German museums was taken away and made fun of. When his friends were arrested by the Gestapo in 1936, it became very dangerous for him.

On January 2, 1937, Schwitters fled to Norway. He was wanted for an "interview" with the Gestapo. His son Ernst had already left Germany. His wife Helma stayed in Hanover to manage their properties. In the same year, his Merz pictures were included in the "Degenerate Art" exhibition in Munich. This made it impossible for him to return home.

Helma visited Schwitters in Norway for a few months each year until World War II began. They last saw each other in June 1939. Schwitters started a second Merzbau in Norway in 1937. But he had to leave it in 1940 when the Nazis invaded. This Merzbau was later destroyed in a fire in 1951.

Internment on the Isle of Man

After the Nazis invaded Norway, Schwitters was interned by the Norwegian authorities. He was held in a school in Kabelvåg. After being released, Schwitters fled to Leith, Scotland, with his son and daughter-in-law. They traveled on a Norwegian patrol ship in June 1940.

Now officially an 'enemy alien' (a citizen of a country at war with Britain), he was moved between internment camps. On July 17, 1940, he arrived at Hutchinson Internment Camp on the Isle of Man.

The camp was in a group of houses around Hutchinson Square in Douglas. By July 1940, there were about 1,205 internees. Most were German or Austrian. The camp became known as "the artists' camp." Many artists, writers, and professors were held there. Schwitters was popular in the camp. He was known as a good storyteller and artist.

He soon got a studio space and taught art to other internees. Many of his students later became important artists. He created over 200 works while interned. He painted many portraits, often charging for them. He showed his portraits in camp art exhibitions. He also wrote for the camp newsletter, The Camp.

At first, there weren't many art supplies. Internees had to be creative. They mixed brick dust with sardine oil for paint. They dug up clay for sculptures. They even used lino floors to make prints.

Schwitters was well-liked and helped distract others from their internment. Fellow internees remembered his unusual habits. He sometimes slept under his bed or barked like a dog. He also gave regular Dadaist readings. However, his epilepsy, which had stopped since childhood, returned. His son thought this was due to Schwitters's sadness about being interned.

Schwitters asked to be released in October 1940. He wrote, "As artist, I can not be interned for a long time without danger for my art." But he was refused. He was finally released on November 21, 1941. This happened with help from Alexander Dorner of the Rhode Island School of Design.

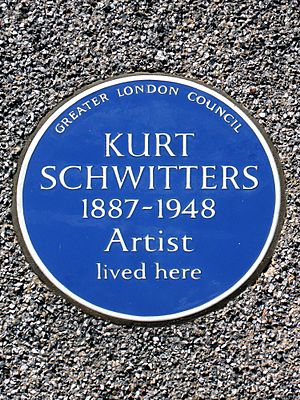

Life in London

After his release, Schwitters moved to London. He hoped to use the connections he had made. He first lived in an attic flat in Paddington.

In London, he met other artists like Naum Gabo and Ben Nicholson. He showed his art in several galleries. But he didn't have much success. At his first solo exhibition in 1944, only one of his forty works was sold.

During his time in London, Schwitters's art changed again. He started to include natural objects and softer colors. For example, Small Merzpicture With Many Parts (1945–46) used pebbles and broken porcelain found on a beach.

In August 1942, he moved with his son to Barnes. In October 1943, he learned that his Merzbau in Hanover had been destroyed by bombing. In April 1944, he had his first stroke. This left one side of his body temporarily paralyzed. His wife Helma died of cancer in October 1944. Schwitters heard about her death in December.

The Lake District and Final Years

Schwitters first visited the Lake District for a holiday in September 1942. He moved there permanently on June 26, 1945, to Ambleside. After another stroke and illness, he moved to an easier-to-access house.

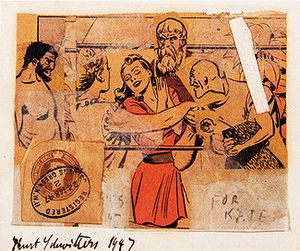

While in Ambleside, Schwitters created some early pop art pictures. One example is For Käte (1947). His friend Kate Steinitz encouraged him. She had moved to the United States and sent him letters describing the new consumer society. She wrapped her letters in comic book pages to show him this new world. She encouraged him to 'Merz' these ideas.

In March 1947, Schwitters decided to rebuild the Merzbau. He found a barn at Cylinders Farm in Elterwater. This barn was owned by Harry Pierce, whose portrait Schwitters had been asked to paint. Schwitters had to paint portraits and landscapes to earn money. But then he received a £1,000 fellowship. This money was meant to help him repair his old Merz constructions. Instead, he used it for the "Merzbarn" in Elterwater.

Schwitters worked on the Merzbarn every day. He traveled five miles between his home and the barn. He only stopped when he was ill. On January 7, 1948, he learned he had been granted British citizenship. The next day, on January 8, Schwitters died in Kendal Hospital. He was 60 years old.

He was buried on January 10 at St. Mary's Church, Ambleside. His grave was unmarked until 1966. A stone was then put up with the words "Kurt Schwitters – Creator of Merz." His body was later moved and reburied in Hanover in 1970. His new grave has a marble copy of his 1929 sculpture Die Herbstzeitlose.

Images for kids

-

Schwitters Merz 1. - Holland Dada, 1923, printed cover of his first Merz-publication

-

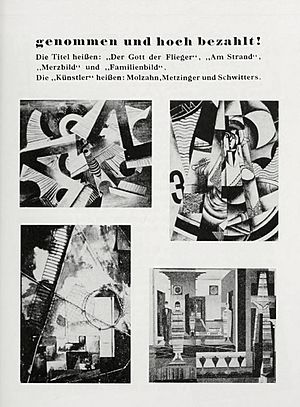

Poster for Dada Matinée, Jan. 1923, printed poster, announcing Kurt Schwitters, Theo van Doesburg & his wife Nelly

Schwitters's Legacy

The Merzbarn Today

One entire wall of the Merzbarn was moved to the Hatton Gallery in Newcastle. This was done to keep it safe. The rest of the barn is still in Elterwater, near Ambleside. In 2011, the barn (but not the artwork inside) was rebuilt at the Royal Academy in London. This was part of an exhibition called Modern British Sculpture.

Influence on Other Artists

Many artists have said that Schwitters was a big influence on their work. These include Ed Ruscha, Robert Rauschenberg, Damien Hirst, and Arman.

Art Market and Forgeries

Schwitters's work Ja-Was?-Bild (1920) was sold for £13.9 million in London in 2014. It was an abstract work made from oil, paper, fabric, wood, and nails.

The Kurt Schwitters Archive at the Sprengel Museum in Hanover keeps a list of fake Schwitters artworks. A collage called "Bluebird" was chosen for the cover of a Tate Gallery exhibition catalog in 1985. But it was removed from the show after Ernst Schwitters said it was a fake.

Cultural Impact

- Brian Eno used a recording of Schwitters's Ursonate in his 1977 song "Kurt's Rejoinder."

- The electronic music group Matmos used Ursonate in their song Schwitt/Urs.

- The Japanese musician Merzbow named his group after Schwitters's art style.

- A fictional story about Schwitters and a boy is told in the opera Man and Boy: Dada.

- The German hip-hop band Freundeskreis quoted from his poem An Anna Blume in their song "ANNA."

- The band Faust has a song called "Dr. Schwitters snippet."

- Chumbawamba included parts of Ursonate in their song "Ratatatay."

- The band British Sea Power grew up near Schwitters's home in Cumbria. They have referenced his work in their songs.

- American author Paul Auster often uses the name Anna Blume in his books.

See also

In Spanish: Kurt Schwitters para niños

In Spanish: Kurt Schwitters para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |