El Lissitzky facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

El Lissitzky

|

|

|---|---|

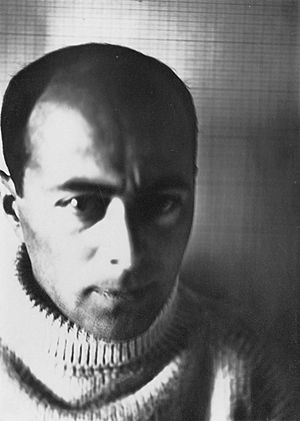

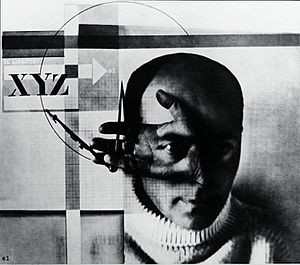

Lissitzky in a 1924 self-portrait

|

|

| Born |

23 November 1890 Pochinok, Smolensk Governorate, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 30 December 1941 (aged 51) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union

|

| Occupation | Artist |

Lazar Markovich Lissitzky (born November 23, 1890 – died December 30, 1941), better known as El Lissitzky, was a famous Russian artist, designer, and photographer. He was also a typographer (someone who designs how text looks) and an architect. He was a very important person in the Russian avant-garde movement, which was a group of artists who created new and experimental art.

Lissitzky helped develop a style called suprematism with his teacher, Kazimir Malevich. He also designed many exhibition displays and posters for the Soviet Union. His work had a big impact on other art movements like the Bauhaus and constructivism. He tried out new ways of making art that later became very popular in 20th-century graphic design.

Lissitzky believed that artists could help change the world. He called this "goal-oriented creation." He started his career by drawing pictures for Yiddish children's books to share Jewish culture in Russia. He began teaching at age 15 and continued teaching throughout his life. He taught in different schools and used various art forms, always sharing and learning new ideas.

He worked with Malevich in an art group called UNOVIS, where they developed suprematism. Lissitzky even created his own version of suprematism called Proun. In 1921, he became a cultural ambassador for Russia in Weimar Germany. There, he worked with and influenced important artists from the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements.

In his later years, he made big changes in typography, exhibition design, photomontage (making pictures from different photos), and book design. He created many respected works and won international awards for his exhibition designs. Even when he was very sick in 1941, he made one of his last works: a Soviet propaganda poster asking people to build more tanks for the fight against Nazi Germany.

Contents

Early Life and Art Beginnings

Lissitzky was born on November 23, 1890, in Pochinok, a small Jewish town in what was then the Russian Empire. As a child, he lived and studied in Vitebsk, which is now part of Belarus. Later, he spent ten years in Smolensk with his grandparents, attending school there. He always loved drawing and showed a lot of talent.

When he was 13, he started taking lessons from Yehuda Pen, a local Jewish artist. By the time he was 15, he was already teaching art to other students. In 1909, he tried to get into an art academy in Saint Petersburg. Even though he passed the entrance exam, he was not accepted. This was because the laws at the time (under the Tsarist regime) only allowed a small number of Jewish students into Russian schools.

Because of this, Lissitzky went to study in Germany, like many other Jewish people from the Russian Empire. In 1909, he began studying architectural engineering at the Darmstadt University of Technology in Germany. In the summer of 1912, Lissitzky traveled through Europe. He spent time in Paris and walked about 750 miles (1,200 km) in Italy. He learned about fine art and sketched buildings and landscapes.

His interest in old Jewish culture grew after meeting a group of Russian Jews in Paris. In 1912, some of his artworks were shown for the first time in an exhibit by the St. Petersburg Artists Union. This was an important first step for him. He stayed in Germany until World War I started. Then, he had to return home through Switzerland and the Balkans. Many other artists from the Russian Empire, like Wassily Kandinsky and Marc Chagall, also had to return.

When he came back to Moscow, Lissitzky went to the Polytechnic Institute of Riga, which had moved to Moscow because of the war. He also worked for architecture companies. During this time, he became very interested in Jewish culture. After the old government (which was against Jewish people) fell, Jewish culture began to flourish again. The new government allowed Hebrew letters to be printed and gave Jewish people more rights.

Lissitzky then focused on Jewish art. He showed works by local Jewish artists and traveled to Mahilyow to study old synagogues. He wrote an article about the art he saw there. He also drew pictures for many Yiddish children's books. These books were his first big step into book design, a field he would greatly influence.

His first designs appeared in a 1917 book called Sihas hulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten. He used Hebrew letters in a style similar to Art Nouveau. His next book was a visual story of the traditional Jewish Passover song Had gadya (One Goat). In this book, Lissitzky used a special design trick: he matched the color of the characters in the story with the words that named them.

On the last page of the book, Lissitzky showed the "hand of God" defeating the angel of death, who wore the tsar's crown. This picture connected the freedom of the Jewish people with the victory of the Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution. Some people think he was worried about the Bolsheviks changing traditional Jewish culture. Pictures of the hand of God appeared in many of his works, especially in his 1924 photomontage self-portrait called The Constructor.

Exploring New Art Styles

Suprematism: A New Way of Seeing

In May 1919, Lissitzky returned to Vitebsk after being invited by his friend, the artist Marc Chagall. He taught graphic arts, printing, and architecture at the new People's Art School. Chagall had created this school after becoming the Commissioner of Artistic Affairs for Vitebsk in 1918. Lissitzky also designed and printed propaganda posters during this time.

Chagall also invited other Russian artists, like the painter Kazimir Malevich and Lissitzky's old teacher, Yehuda Pen. In October 1919, Lissitzky convinced Malevich to move to Vitebsk. Malevich brought many new ideas that inspired Lissitzky. However, these ideas clashed with the local artists and Chagall himself, who preferred more traditional art.

Malevich was developing and promoting his ideas on suprematism. This art style, which started around 1915, rejected drawing natural shapes. Instead, it focused on creating clear, geometric forms. Malevich changed the school's teaching program to his own and spread his suprematist ideas throughout the school. Chagall preferred more classical art, and Lissitzky was caught between the two styles. In the end, Lissitzky chose Malevich's suprematism and moved away from traditional Jewish art. Chagall left the school soon after.

At this point, Lissitzky fully supported suprematism and helped Malevich develop it further. From 1919 to 1920, Lissitzky led the Architectural department at the People's Art School. There, he and his students worked on changing suprematism from flat shapes to three-dimensional forms.

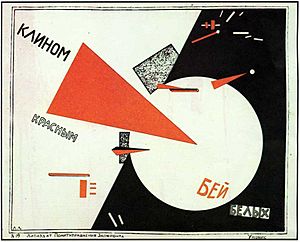

One of Lissitzky's most famous works from this time was the 1919 propaganda poster "Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge". Russia was in a civil war then. The "Reds" were communists and revolutionaries, and the "Whites" were against them. The simple image of a red wedge breaking a white shape sent a strong message. This piece is often seen as one of Lissitzky's first big steps away from Malevich's pure suprematism into his own unique style. He said that an artist creates a new symbol that shows a new world being built.

In January 1920, Malevich and Lissitzky started an art group called UNOVIS (Exponents of the new art). This group included students, professors, and other artists. Under Malevich's leadership, the group worked on a "suprematist ballet" and a remake of an old futurist opera called Victory Over the Sun. Lissitzky and the group decided to share credit for their works, signing most pieces with a black square. This was a tribute to Malevich and a symbol of their support for Communism. This black square became the official symbol of UNOVIS.

The UNOVIS group, which ended in 1922, was very important in spreading suprematist ideas in Russia and other countries. It helped make Lissitzky one of the leading artists of the avant-garde.

Proun: Bridging Art and Architecture

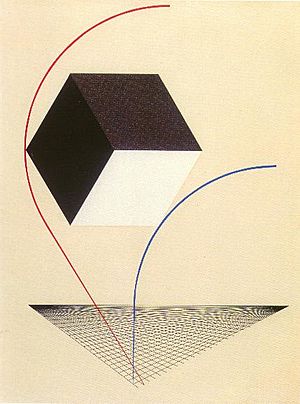

During this time, Lissitzky developed his own suprematist style. He created a series of abstract, geometric paintings that he called Proun. The exact meaning of "Proun" was never fully explained. Some think it means "designed by UNOVIS" or "Design for the confirmation of the new." Lissitzky later described them as "the station where one changes from painting to architecture."

Proun was Lissitzky's way of exploring suprematism's visual language using spatial elements. He used shifting angles and multiple viewpoints, which were new ideas in suprematism. At that time, suprematism mostly used flat, 2D shapes. Lissitzky, who loved architecture and 3D ideas, wanted to expand suprematism beyond this.

His Proun works lasted for more than five years. They started as simple paintings and lithographs and grew into full three-dimensional installations. They also laid the groundwork for his later work in architecture and exhibition design. These paintings were art on their own, but they were also important for developing his early ideas about buildings. In these works, the basic parts of architecture—like volume, mass, color, space, and rhythm—were rethought using new suprematist ideas. Through his Prouns, he created ideal models for a new and better world. This idea of creating art with a social purpose can be summed up by his phrase "task-oriented creation."

Sometimes, Jewish themes and symbols appeared in his Prounen. Lissitzky often used Hebrew letters as part of the design. For example, on the cover of the 1922 book Arba'ah Teyashim (Four Billy Goats), he arranged Hebrew letters like architectural parts in a dynamic design, similar to his Proun typography. This theme also appeared in his illustrations for the Shifs-Karta (Passenger Ticket) book.

Back to Germany: Spreading New Ideas

In 1921, around the time UNOVIS ended, suprematism began to split. One group liked art that was spiritual and ideal, while the other preferred art that was useful for society. Lissitzky didn't fully belong to either group and left Vitebsk in 1921. He took a job as a cultural representative for Russia and moved to Berlin. His goal was to connect Russian and German artists.

In Berlin, he also worked as a writer and designer for international magazines. He helped promote avant-garde art through various gallery shows. He started a short-lived but important magazine called Veshch-Gegenstand Objekt with the Russian-Jewish writer Ilya Ehrenburg. This magazine aimed to show modern Russian art to Western Europe. It covered many arts, focusing on new suprematist and constructivist works, and was published in German, French, and Russian.

During his time in Berlin, Lissitzky also grew his career as a graphic designer. He created some historically important works, such as the books Dlia Golossa (For the Voice), a collection of poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Die Kunstismen (The Artisms) with Jean Arp. In Berlin, he met and became friends with many other artists, including Kurt Schwitters, László Moholy-Nagy, and Theo van Doesburg.

With Schwitters and van Doesburg, Lissitzky proposed an international art movement based on constructivism. He also worked with Kurt Schwitters on an issue of the magazine Merz and continued to illustrate children's books. After his first Proun series was published in Moscow in 1921, Schwitters introduced Lissitzky to a gallery in Hanover. There, Lissitzky had his first solo exhibition. His second Proun series, printed in Hanover in 1923, was very successful because it used new printing techniques. Later, he met Sophie Küppers, whom he married in 1927.

Horizontal Skyscrapers: Buildings in the Air

From 1923 to 1925, Lissitzky came up with an idea for horizontal skyscrapers. He called them Wolkenbügel, which means "cloud-hangers" or "sky-hangers." He planned a series of eight such buildings for the main intersections of the Boulevard Ring in Moscow. Each Wolkenbügel would be a flat, three-story, 590-foot (180-meter) wide L-shaped slab. It would be raised 164 feet (50 meters) above street level.

These buildings would rest on three tall supports (each about 33x52x164 feet or 10x16x50 meters). One support would go underground and lead to a subway station. The other two would provide shelter for tram stations at street level.

Lissitzky believed that since humans move horizontally on the ground, buildings should also spread out horizontally in the air when there isn't enough land. He thought this was better than building very tall, American-style towers. He also argued that these horizontal buildings would have better insulation and ventilation.

Lissitzky knew his ideas were very different from the existing city. So, he experimented with different shapes and sizes for his horizontal buildings to make them look balanced. The raised platform was designed so that each of its four sides looked different. All eight buildings were planned to be identical, so Lissitzky suggested using color-coding to help people find their way around.

After creating these "paper architecture" projects, Lissitzky was hired to design a real building in Moscow. Located at 17, 1st Samotechny Lane, it is Lissitzky's only actual building. It was ordered in 1932 by Ogonyok magazine to be used as a print shop. In 2007, a group tried to get the building listed as a historical site, but it didn't happen. In 2008, the abandoned building was badly damaged by fire.

Exhibitions and Later Designs

After two years of intense work, Lissitzky became very ill with pneumonia in October 1923. A few weeks later, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. In February 1924, he moved to a Swiss sanatorium (a special hospital for long-term illness). He stayed very busy there, designing advertisements and translating articles by Malevich into German. He also experimented a lot with typography and photography.

In 1925, the Swiss government did not let him renew his visa, so Lissitzky returned to Moscow. He began teaching interior design, metalwork, and architecture at Vkhutemas (State Higher Artistic and Technical Workshops). He taught there until 1930. He mostly stopped his Proun works and became more involved in architecture and propaganda designs.

In June 1926, Lissitzky left Russia again for a short time in Germany and the Netherlands. There, he designed exhibition rooms for art shows in Dresden and Hanover. He also improved his Wolkenbügel concept with another architect, Mart Stam. In his autobiography, Lissitzky wrote that his most important work as an artist began in 1926 with the creation of exhibitions.

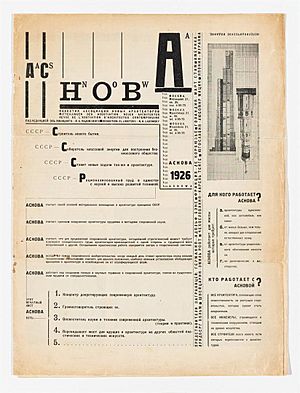

In 1926, Lissitzky joined Nikolai Ladovsky's Association of New Architects (ASNOVA) and designed the only issue of their journal, Izvestiia ASNOVA.

Back in the USSR, Lissitzky designed displays for the official Soviet pavilions at international exhibitions, including the 1939 New York World's Fair. One of his most famous exhibits was the All-Union Polygraphic Exhibit in Moscow in 1927. Lissitzky led the design team for "photography and photomechanics" (which included photomontage) artists. His work was seen as very new and different, especially compared to the more traditional designs of other artists.

In early 1928, Lissitzky visited Cologne to prepare for the 1928 Pressa Show. He was in charge of the Soviet program. Instead of building their own pavilion, the Soviets rented the largest building at the fair. Lissitzky's design focused on showing films, with continuous presentations of new movies, newsreels, and early animation on many screens. His work was praised because it used very few paper exhibits; "everything moves, rotates, everything is energized." Lissitzky also designed other exhibitions, like the 1930 Hygiene show in Dresden.

Along with designing pavilions, Lissitzky started experimenting with print media again. His work with book and magazine design was some of his most impressive and influential. He brought new ideas to typography and photomontage, two areas where he was very skilled. In 1930, he even designed a photomontage birth announcement for his new son, Jen. The image showed baby Jen over a factory chimney, connecting his future with his country's industrial progress. Around this time, Lissitzky's interest in book design grew even more. In his remaining years, he created some of his most challenging and new works in this field.

He saw books as lasting objects with power. This power was special because books could share ideas with people from different times, cultures, and interests in ways other art forms could not. This goal was part of all his work, especially in his later years. Lissitzky wanted to create art that had power and purpose, art that could bring about change.

Final Years and Legacy

In 1932, Joseph Stalin closed down independent artists' groups. Artists who had been part of the avant-garde had to change their style or risk being criticized. Lissitzky kept his reputation as a master of exhibition art and management into the late 1930s. His tuberculosis slowly made him weaker, and he relied more and more on his wife to help him finish his work.

In 1937, Lissitzky was the main decorator for the upcoming All-Union Agricultural Exhibition. His artwork for this exhibition was very different from his modernist art of the 1920s. It moved towards socialist realism, a style that showed realistic images of Soviet life. Lissitzky even suggested the famous statue of Stalin in front of the central pavilion.

He also worked on decorating the Soviet pavilion for the 1939 New York World's Fair, but his design was eventually not chosen.

Lissitzky's work on the USSR in Construction magazine pushed his ideas about book design to an extreme. In one issue, he included multiple fold-out pages that combined with other folded pages to create unique designs and a story structure. Each issue focused on a specific topic of the time, like a new dam or the Red Army's progress.

In 1941, his tuberculosis got worse, but he continued to create art. One of his last works was a propaganda poster for Russia's efforts in World War II, titled "Davaite pobolshe tankov!" (Give us more tanks!). He died on December 30, 1941, in Moscow.

Images for kids

-

Lissitzky in a 1924 self-portrait

See also

In Spanish: El Lisitski para niños

In Spanish: El Lisitski para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |