Ilya Ehrenburg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ilya Ehrenburg

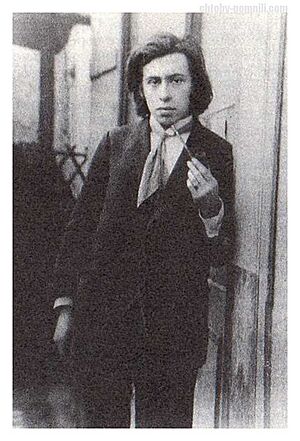

|

|

|---|---|

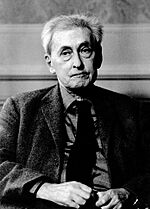

Ehrenburg in 1959

|

|

| Born | January 26 [O.S. January 14] 1891 Kiev, Russian Empire |

| Died | August 31, 1967 (aged 76) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (now Moscow, Russia) |

| Notable works | Julio Jurenito, The Thaw |

| Signature | |

|

|

Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg (Russian: Илья́ Григо́рьевич Эренбу́рг; January 26, 1891 – August 31, 1967) was a famous Soviet writer, journalist, and historian. He was also involved in politics during his time.

Ehrenburg wrote many books, around one hundred in total. He was best known for his novels and his work as a journalist, especially as a reporter during three major wars: First World War, Spanish Civil War, and Second World War. His articles during World War II, called the Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union, encouraged Soviet soldiers to fight bravely against the German invaders. These articles were very popular with soldiers but also caused some debate because they seemed to be against all German people. Ehrenburg later explained that he was only writing about the German soldiers who invaded Soviet land, not all Germans.

One of his most famous novels, The Thaw, even gave its name to a period in Soviet history. This period, known as the Khrushchev Thaw, was a time of more freedom after the death of Joseph Stalin. Ehrenburg also wrote popular travel books and a very important memoir called People, Years, Life. He also helped edit The Black Book, which told the story of the Holocaust (the killing of Jewish people) in the Soviet Union by the Nazis. This book was not allowed to be published in the Soviet Union for a long time.

Ehrenburg also wrote many poems throughout his life.

Contents

Who Was Ilya Ehrenburg?

Ilya Ehrenburg was born in Kiev, Ukraine, which was part of the Russian Empire at the time. His family was Jewish, and his father was an engineer. His family was not very religious, and Ehrenburg himself never practiced Judaism. He considered himself Russian and later a Soviet citizen, and he always wrote in Russian, even when he lived abroad for many years. He strongly spoke out against antisemitism (hatred of Jewish people) and later gave all his personal papers to Yad Vashem in Israel, a memorial to Holocaust victims.

When he was four years old, his family moved to Moscow. There, he met Nikolai Bukharin at school, who became a lifelong friend.

Early Life and Political Involvement

After the Russian Revolution of 1905, Ehrenburg and his friend Bukharin became involved in the illegal activities of the Bolshevik group. In 1908, when Ehrenburg was 17, the secret police arrested him for five months. He was treated roughly and lost some teeth. After his release, he was allowed to leave the country and chose to live in Paris, France.

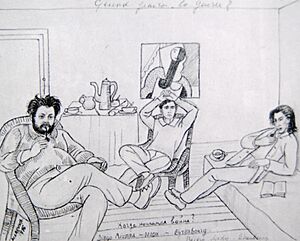

In Paris, he first joined the Bolshevik group again and met Vladimir Lenin, a key leader. But he soon left these political groups and became interested in the artistic and free-spirited life in the Montparnasse area of Paris. He started writing poems and spent time with many famous artists like Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani.

Ehrenburg as a War Correspondent

During World War I, Ehrenburg became a war correspondent (a journalist who reports from a war zone) for a newspaper in Russia. He wrote many articles about the war, which were later published as a book called The Face of War. His poems also began to focus on war and destruction.

In 1917, after the Russian Revolution, Ehrenburg returned to Russia. He was shocked by the violence he saw and at first disagreed with the Bolsheviks. He experienced many changes in power in Kiev and eventually settled in Moscow. He was briefly arrested but soon released.

He became a well-known Soviet writer and journalist, often traveling abroad. He wrote interesting novels and short stories, many of which were set in Western Europe.

Reporting on the Spanish Civil War

Because he was friends with many European left-wing thinkers, Stalin often allowed Ehrenburg to travel to Europe. He went to Spain in 1936 as a reporter for the newspaper Izvestia during the Spanish Civil War. He reported on the war and was also involved in some propaganda efforts. In 1937, he attended a meeting of writers in Spain to discuss how intellectuals should respond to the war. Many famous writers, including Ernest Hemingway, were there.

Ehrenburg During World War II

Days after Germany invaded the Soviet Union, Ehrenburg was given a regular column in Krasnaya Zvezda, the newspaper for the Red Army. During the war, he wrote over 2,000 articles. He saw the war as a fight between good and evil, showing Soviet soldiers as heroes fighting a cruel German enemy.

In 1943, Ehrenburg started collecting information for The Black Book of Soviet Jewry, which documented the Holocaust (the mass murder of Jewish people) in the Soviet Union. In 1944, he wrote that the murder of six million Jews was the Germans' worst crime.

His articles, which called for revenge against the German enemy, were very popular with Soviet soldiers. However, some people criticized him for encouraging hatred against all Germans. Ehrenburg later clarified that he only meant the German soldiers who invaded Soviet land.

After the war, some of his earlier writings were seen as encouraging violence against German civilians. In 1945, Adolf Hitler even mentioned Ehrenburg, saying he wanted the German people "exterminated." After some criticism in the Soviet newspaper Pravda, Ehrenburg repeated that he never meant to wipe out the entire German people, only the armed invaders.

Later Life and Writings

In 1948, Ehrenburg published an article that signaled a change in Soviet policy towards Israel. After this, many Jewish intellectuals in the Soviet Union were arrested or executed in what was called the "anti-cosmopolitan campaign." Ehrenburg himself was almost arrested, but Stalin decided against it. He was allowed to keep publishing and traveling abroad, possibly to hide the anti-Jewish campaign happening in the Soviet Union.

In 1952, Ehrenburg received the Stalin Peace Prize.

In 1954, Ehrenburg published his famous novel The Thaw. This book explored the limits of censorship in the Soviet Union after Stalin's death. It showed a factory boss who was unfair and controlling, like a "little Stalin." The novel used the idea of a spring thaw (when snow melts) to represent a time of change and more freedom after the strict rule under Stalin. The novel was criticized by some who thought it was too dark, but it gave its name to the entire period of liberalization, the Khrushchev Thaw.

Ehrenburg is also very well known for his memoirs, People, Years, Life. In this book, he was one of the first Soviet writers to mention positively many authors who had been banned under Stalin. However, he also criticized some Russian and Soviet intellectuals who had rejected communism or moved to the West.

His memoirs caused some debate. Some critics accused him of not speaking out enough against injustices during Stalin's time. Ehrenburg argued that he had never seen anyone else protest the arrests happening then.

He continued to write poetry until his last days, focusing on events from World War II, the Holocaust, and the lives of Russian intellectuals. He also helped publish the works of Osip Mandelstam, another important poet, after Mandelstam was officially recognized again following Stalin's death.

Death and Legacy

Ilya Ehrenburg died in 1967. He was buried in Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. His gravestone has a picture of him drawn by his friend, the famous artist Pablo Picasso.

A writer named S.L. Shneiderman later wrote a biography of Ehrenburg, defending him from accusations that he had helped Stalin harm Soviet Jewish culture.

English Translations of Ehrenburg's Works

- The Love of Jeanne Ney, 1930.

- The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenito and his Disciples, 1930.

- A Soviet Writer Looks at Vienna, 1934.

- The Fall of Paris, 1943. (novel)

- The Tempering of Russia, 1944.

- European Crossroad: A Soviet Journalist In the Balkans, 1947.

- The Storm, 1948.

- The Thaw, 1955.

- The Ninth Wave, 1955.

- The Stormy Life of Lasik Roitschwantz, 1960.

- A Change of Season, 1962. (includes The Thaw and its sequel The Spring)

- Chekhov, Stendhal and Other Essays, 1963.

- Memoirs: 1921–1941, 1963.

- Life of the Automobile, 1976.

- The Second Day, 1984.

- The Fall of Paris, 2002.

- My Paris, 2005.

See also

In Spanish: Iliá Ehrenburg para niños

In Spanish: Iliá Ehrenburg para niños