Lion Capital of Ashoka facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Lion Capital of Ashoka |

|

|---|---|

Four Asiatic lions stand back to back on a circular abacus. The Buddhist wheel of the moral law appears in relief below each lion. Between the chakras appear four animals in profile—horse, bull, elephant, and lion. The architectural bell below the abacus, is a stylized upside-down lotus

|

|

| Material | Sandstone |

| Height | 2.1 metres (7 ft) |

| Width | 86 centimetres (34 in) (diameter of abacus) |

| Created | 3rd century BCE |

| Discovered | F. O. Oertel (excavator), 1904–1905 |

| Present location | Sarnath Museum, India |

| Registration | A 1 |

The Lion Capital of Ashoka is the top part, or capital, of a tall stone column built by Emperor Ashoka the Great. This column was set up in Sarnath, India, around 250 BCE.

The most famous part of the capital is its four life-sized Asiatic lions. They stand back-to-back on a round base called an abacus. This abacus has carvings of wheels and four animals: a lion, an elephant, a bull, and a galloping horse. Below the abacus is a bell-shaped lotus flower. The entire capital is about 2.1 metres (7 ft) tall. It was carved from a single block of polished sandstone.

Emperor Ashoka built this column after he became a Buddhist. It marked the place where Gautama Buddha gave his very first sermon about 200 years earlier.

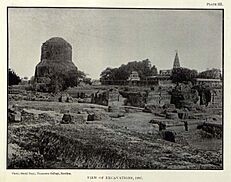

Over time, the capital fell and was buried. It was found by archaeologists in 1904–1905. The column itself, which had broken, remains at its original spot in Sarnath. The Lion Capital was in better shape, though it had some cracks and two lions had damaged heads. Today, you can see it at the Sarnath Museum, which is near where it was found.

This capital is one of the first important stone sculptures found in South Asia after the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation. Its sudden appearance and its polished look have made experts wonder if skilled stone carvers from Iran helped create it. Others believe that Indian artists, who were used to working with wood and copper, simply started using stone. The Lion Capital is full of important meanings, both Buddhist and general.

In 1947, when India was becoming independent, the wheel from the capital's abacus was chosen for the new national flag. The capital itself, without the lotus, became the state emblem.

Contents

Finding the Ancient Capital

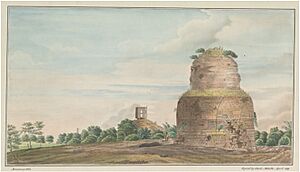

Sarnath has been visited and explored for a long time. In 1780, a painter named William Hodges saw the Dhamek Stupa, a large monument there. Later, in 1794, people dug for bricks near the stupa.

In 1861, Alexander Cunningham, a famous archaeologist, tried to dig into the Dhamek Stupa. He didn't find relics, but he noticed small models of the stupa scattered around. This made him believe that the Dhamek Stupa was indeed where the Buddha gave his first sermon.

Later, archaeologists used old travel writings to help their search. A Chinese pilgrim named Xuanzang visited India from 629 CE to 645 CE. He wrote about a tall, shiny pillar near Varanasi that Ashoka had built. Another Chinese visitor, Faxian, also wrote about Sarnath in the early 400s CE. These accounts hinted that there might have been more Ashokan pillars in ancient India than we see today.

Even though Buddhism faced challenges in some parts of India, it remained strong in central and northeastern areas for a long time. Historians say that temples were often targets during conquests. However, many Hindu and Jain temples survived if they were used by ordinary people, not just royalty. Buddhist monasteries, on the other hand, often relied on kings for support. When these kings lost power, the monasteries suffered.

Sarnath was not always a peaceful place. After the 12th century, very few Buddhists remained in India. The site was even damaged again in 1894 when many bricks were taken to build a railway line.

Excavation and Display

F. O. Oertel, an engineer, was in charge of public works in Varanasi. He built a storage place for artifacts found at Sarnath and paved the road to the site. He then convinced John Marshall, the head of the ASI, to let him dig at Sarnath in the winter of 1904–05. Marshall also decided that a museum should be built nearby to keep the discovered items safe.

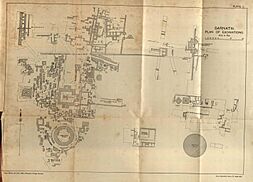

Oertel started digging near the Jagat Singh stupa. This stupa is southwest of the Dhamek Stupa. He then moved to the Main Shrine, north of the stupa. It was west of this shrine that he found the buried parts of Ashoka's pillar and soon after, its famous lion capital.

The Sarnath Museum, also known as the Archaeological Museum Sarnath, was finished in 1910. It was the first museum built right at an archaeological site by the ASI. The Lion Capital has been on display there ever since. Daya Ram Sahni, an Assistant Superintendent of the ASI, helped organize the museum's collection. He also wrote a detailed catalog of the museum's items in 1914.

What the Capital Looks Like

The entire capital is about 2.1 metres (7 ft) tall. Its lowest part is an upside-down lotus flower, about 61 centimetres (2 ft) high. This lotus has 16 petals and is carved in a style similar to ancient Persian art.

Above the lotus is a round slab called an abacus. It is about 86 centimetres (34 in) wide and 34 centimetres (13+1⁄2 in) high. On top of the abacus sit four lions, each about 1.1 metres (3+3⁄4 ft) tall. They are placed back-to-back, facing the four main directions. Experts have debated if the lions are standing or sitting, but many describe them as "standing back-to-back."

Two of the lions were found in good condition. The heads of the other two had broken off before being buried. When found, these heads needed to be reattached. One damaged lion was missing its lower jaw, and the other its upper jaw. These missing parts have never been found.

On the side of the abacus, below each lion, is a carved wheel with 24 spokes. Between these wheels are four animals carved in high relief. They are a lion, an elephant, a bull, and a horse. The first three animals look like they are walking, but the horse is shown at a full gallop. The capital was carved from a single piece of stone. It is broken across its "neck" just above the lotus.

The capital has a very shiny, polished surface. This shine was likely achieved by carefully polishing fine-grained sandstone. The pillar that held the capital is now broken into several pieces at the site. It is protected by a glass enclosure for visitors. It is believed that a metal pin once held the capital firmly to the pillar.

The lions once supported a larger wheel on top, which is now mostly lost. This wheel, called the dharmachakra, symbolized the Buddhist wheel of moral law. Only small pieces of this wheel and parts of its spokes have been found. These fragments are also displayed in the Sarnath Museum. The original wheel was thought to be about 0.84 metres (2+3⁄4 ft) wide.

Interestingly, the lions did not have carved eyeballs. Instead, precious stones were placed in their eye sockets. These stones were held in place by small iron pins. Although the stones are gone, one pin was still in a lion's eye when the capital was discovered.

Meaning of the Symbols

The Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath is one of the first times lions are shown in art in South Asia. Some scholars think lions were brought to India from western Asia for royal hunts. This might explain why they became a symbol of royal power. After Emperor Ashoka became a Buddhist, he changed the meaning of the lion. It went from being a symbol of royal power to also representing royal strength combined with peace. In early Buddhist art, the lion, horse, elephant, and bull were all considered lucky animals.

The Lion Capital and Ashoka's pillar have many deep meanings. The four lions on the abacus, and the one carved on its rim, are linked to the Buddha himself. One of Buddha's names was Shakyasimha, meaning "lion of the Shakya clan." The other three animals on the abacus also relate to events in Prince Siddhartha's (Buddha's) life. The elephant reminds us of his mother's dream about his birth. The horse represents his departure from the palace. The bull is linked to his first meditation.

The abacus and its animals have also been connected to a mythical lake called Anavatapta. In this myth, water flowed from the lake, splitting into four streams from the mouths of these same four animals. These streams then flowed to the four corners of the earth, like the Buddha's message spreading everywhere. The pillar itself is seen as a connection between the earth and the heavens, like the world's axis.

The four lions are also thought to represent the four main directions. They are like the Buddha roaring his message to the farthest parts of the world. A Buddhist text, the Maha-Sihanada Sutta, directly links the wheel and the lion. It says the Buddha "roars his lion’s roar... and sets rolling the Wheel of Dharma." Some interpretations suggest the small animals on the abacus also represent the cardinal directions: lion (north), elephant (west), bull (south), and horse (east). The smaller wheels might represent the solstices and equinoxes.

The lotus flower at the bottom of the capital is also symbolic. In Buddhism, the lotus grows clean and pure from muddy water, just as the Buddha rose above an impure world to find enlightenment.

Scholars have also discussed the meaning of the wheels. The large wheel that was once on top, and the four smaller ones on the abacus, are often seen as the Buddhist wheel of moral law, the dharmachakra. This wheel symbolizes the spread of Buddha's message. Others believe they were more general symbols of good leadership, showing Ashoka as a chakravartin, a "wheel-turner" or a universal ruler. Overall, the symbolism of the Sarnath column and capital is thought to be more Buddhist than secular.

Some historians have also argued that the symbols, like the dharmachakra, were not only Buddhist. They existed in the Vedic period before Buddhism. The dharmachakra could also represent the "Revolution of the year" or "Father Time." This idea helped in choosing the "Sarnath wheel" for the Indian national flag.

The lotus bell at the bottom has also been debated. Some say it's an Indian symbol, like a "vase of plenty" overflowing with lotus petals. Others argue it was inspired by Persian designs.

Influences on the Art

Many experts have discussed where the ideas and style for Ashoka's pillars came from. In 1911, historian Vincent Smith suggested that the pillars, including the Sarnath capital, looked "foreign." He thought their smooth shine, lotus bases, and stylized lions pointed to Iranian carvers. These carvers might have moved to the Mauryan Empire after Alexander the Great attacked Persepolis in 330 BCE.

John Marshall also believed the Sarnath capital was made by foreign artists working in India. He compared it to other Indian art and found the capital to be different. The realistic details of the lions, like their muscles and skin folds, made some wonder about the origin of Mauryan art.

Mortimer Wheeler even suggested that before the Mauryan period, Indian art was mostly folk art. He thought that Hellenistic (Greek-influenced) craftsmen might have been hired by Emperor Ashoka.

However, other scholars have disagreed. John Irwin argued that not all pillars were made for Ashoka; some might have been adapted. He also pointed out that the lively bull and elephant carvings show a deep knowledge of Indian animals, not just Iranian ones. Irwin believed Ashoka used an existing Indian tradition of pillars as symbols of the "axis of the world."

More recently, scholars like Frederick Asher have supported the idea that the pillars were indeed from Ashoka's time. He also suggests that the appearance of stone sculpture in South Asia during the Mauryan period was due to Ashoka's active connection with the wider world, not just a simple copying of foreign styles.

Upinder Singh noted that the Asiatic lion became a strong symbol of political power in India before Ashoka's time. Ashoka, as a powerful ruler and a Buddhist, wanted new symbols. So, while his lions looked similar to Persian ones, the idea of using a pair of back-to-back lions to show both spiritual and worldly power was new.

Christopher Ernest Tadgell thinks it's likely that Persian immigrants helped carve Ashoka's capital. But he also believes Ashoka's success came from using the existing Indian worship of pillars as the world's axis.

Harry Falk agrees that Mauryan stonework owed something to Iranian art. He highlights Ashoka's bold vision in creating such huge, single-piece pillars with incredibly realistic lions and bulls.

Richard Stoneman suggests that when looking at sculpture, we should separate carving techniques from the choice of subject. He says that copying is not the only way influences happen; interaction and creative re-use are more likely. He notes that the Sarnath lions show Greek influence in their realistic details, even if the overall form is Eastern.

Legacy

The Sarnath capital played a very important role in India's independence. It became the model for both the state emblem and the national flag of the new Dominion of India. This choice aimed to give India symbols of ethical and rightful rule.

On July 22, 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru, who would become India's first prime minister, proposed the design for the national flag. He said the flag should have three colors and a navy blue wheel in the center. This wheel would be based on the Chakra (wheel) from the Sarnath Lion Capital. His proposal was accepted in December 1947. Nehru wanted the dharmachakra to represent peace and internationalism, just as he believed it did in Ashoka's time.

After Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism, the meaning of the lion changed. It became a symbol of peace, not just imperial power. Ashoka's lion capital has even been used in memorials on battlefields. For example, in Ypres, Belgium, there is a memorial to Indian soldiers who died in World War I. This memorial uses a replica of the Ashokan lion capital. This symbolizes Ashoka's change to a non-violent approach after a great battle, making it a fitting symbol for a "city of peace."

Reconstructions

Many ideas have been suggested for how the Sarnath pillar and its capital originally looked. The large wheel on top could have rested directly on the lions' backs, or it could have been positioned higher. The full pillar is usually shown as a tall column supporting the capital, with the larger wheel on top.

Related Sculpture

Over many centuries, the Lion Capital of Ashoka became an important artistic model. It inspired many other sculptures in India and beyond.

-

Kushan Empire lion capital, 2nd century CE.

-

Lion capital from Sanchi, with remains of a wheel, circa 600 CE.

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |