Hector Guimard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hector Guimard

|

|

|---|---|

Hector Guimard (1907)

|

|

| Born | 10 March 1867 Lyon, France

|

| Died | 20 May 1942 (aged 75) New York City, United States

|

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings |

|

Hector Guimard (French pronunciation: [ɛktɔʁ ɡimaʁ], 10 March 1867 – 20 May 1942) was a famous French architect and designer. He was a key figure in the Art Nouveau style. This style uses curvy, natural shapes, often inspired by plants.

Guimard became well-known for his design of the Castel Beranger. This was the first Art Nouveau apartment building in Paris. In 1899, it was chosen as one of the best new building designs in the city. He is most famous for the beautiful glass and iron canopies. These canopies, with their curvy Art Nouveau designs, covered the entrances of the first Paris Metro stations.

Between 1890 and 1930, Guimard designed about fifty buildings. He also created 141 subway entrances for the Paris Metro. Besides buildings, he designed many pieces of furniture and other decorative items. However, the Art Nouveau style became less popular in the 1910s. By the 1960s, many of his works were torn down. Only two of his original Metro entrances remained. Guimard's work became popular again in the 1960s. This was partly because the Museum of Modern Art bought some of his designs. Today, art experts recognize how original and important his work was.

Contents

Early Life and Training

Hector Guimard was born in Lyon, France, on March 10, 1867. His father was an orthopedist, a doctor who treats bone and muscle problems. His mother worked with linen.

In 1882, Hector started studying at the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs. This was a school for decorative arts. After getting his diploma in 1887, he went on to study architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts. He won awards in several architecture contests. He also showed his paintings in Paris. From 1891 to 1900, he taught drawing at the decorative arts school.

In 1895, Guimard traveled to Belgium. There, he met Victor Horta, a Belgian architect. Horta was one of the first people to create the Art Nouveau style. Guimard saw Horta's Hotel Tassel, which had flowing, plant-like lines. This visit greatly influenced Guimard's own style and career.

Early Career (1888–1898)

First Buildings

Guimard's first building was a cafe-restaurant called Au Grand Neptune in 1888. It was built for the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889. It was a nice building but not very new in style. It was torn down in 1910. He also built the Pavilion of Electricity for the Exposition.

From 1889 to 1895, he built about a dozen apartment buildings and houses. These included the Hotel Roszé (1891) and the Hotel Jassedé (1893). These early works did not get much attention. He mostly earned money from teaching.

The Famous Castel Béranger

Guimard's first big success was the Castel Béranger in Paris. This apartment building had 36 units and was built between 1895 and 1898. Guimard was only 30 years old. He convinced his client, Mme. Fournier, to use a new, modern style. This style was inspired by Horta's Hotel Tassel.

Guimard used many different artistic effects and dramatic touches. He used cast iron, glass, and ceramics for decoration. The lobby looked like an undersea cave with curvy iron designs and colorful tiles. He designed every small detail, from wallpaper to door handles. He even added a modern telephone booth in the lobby.

Guimard was good at promoting his work. He had his own apartment and office in the building. He held meetings and got articles written about it. He even wrote a book about the building. In 1899, the Castel Béranger won a prize for being one of the best new building facades in Paris. He proudly had this fact carved on the building's front.

Middle Career (1898–1914)

Castles, Villas, and a Concert Hall

The success of the Castel Béranger brought Guimard many new projects. Between 1898 and 1900, he built three very different houses. Each one clearly showed his unique style.

The first was the Maison Coilliot in Lille. It was built for a ceramics maker and served as his shop, office, and home. Its front was covered with green tiles and had soaring arches and curvy ironwork.

In 1899, he started three more houses:

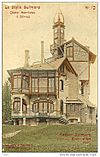

- The Modern Castel (Villa Canivet) in Garches was his modern take on a medieval castle.

- La Bluette in Hermanville-sur-Mer was his modern version of traditional Norman architecture.

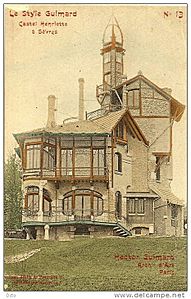

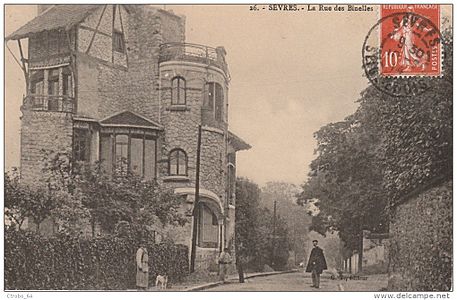

- The Castel Henriette in Sevres was the most creative. It had a tall, thin watchtower. Guimard moved the stairs to the side to create more open space inside. He also designed all the furniture. Sadly, the watchtower fell in 1903, possibly from lightning. The building was later torn down in the 1960s. Some of its furniture is now in museums.

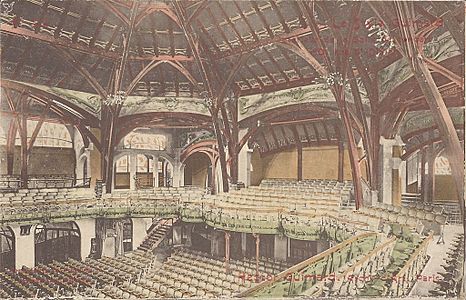

In 1898, Guimard also started building a concert hall, the Salle Humbert-de-Romans. It was meant to be part of a music school for orphans. Guimard designed a grand hall with iron and glass, inspired by an old idea from Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. The hall was finished in 1901. However, the project faced problems, and the hall was used only for meetings. It closed in 1904 and was torn down in 1905.

Paris Metro Entrances

The success of the Castel Béranger led to Guimard's most famous work: the entrances for the new Paris Metro. The Metro was planned to open in 1900 for the Paris Universal Exposition.

A competition was held for station entrances. Guimard did not enter at first. The other designs were criticized for looking like newspaper stands or public toilets. With little time left, Guimard showed his own ideas for iron and glass entrances. These were quicker and simpler to build. He was given the job in January 1900, just months before the Metro opened.

Guimard created two main designs for the covered entrances, called Type A and B. Both used cast iron frames with glass roofs. Type A was simpler and more boxy. Type B was rounded and looked more like a dragonfly. Only one Type B entrance, at Porte Dauphine, still stands in its original spot.

He also designed simpler entrances without roofs. These had decorative green iron railings and two tall posts with lamps. The posts had a unique plant-like shape that Guimard invented. The word "Métropolitain" was written in a special font he created. These were the most common type of entrance.

Guimard's Metro entrances were controversial from the start. Some people thought they didn't match the older buildings around them. In 1904, the entrance at the Opera station was removed because it didn't fit with the Palais Garnier opera house.

Guimard also had disagreements with the Metro authorities about his pay. In 1903, they reached an agreement. Guimard got paid, but he gave up his design rights. New stations continued to use his designs without his direct involvement. Between 1900 and 1913, 167 entrances were built. Today, 66 of them still exist, though many are in different locations.

Later Villas

In the early 1900s, Guimard's popularity started to fade. He built fewer new projects. He was mostly supported by a rich client, Léon Nozal, and his friends.

For this group, he designed:

- La Sapiniere, a small beach house.

- La Surprise, a villa.

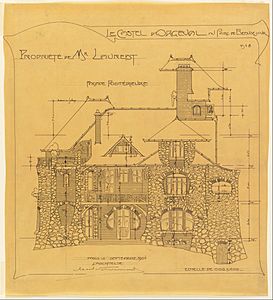

- The Castel Val at Auvers-sur-Oise.

- The Hotel Nozal in Paris.

- The Hotel Jassadé.

- The grand Castel d'Orgeval, which was the main building in a new housing area.

The Hôtel Guimard

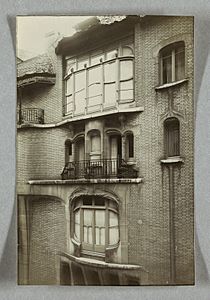

One of his most important works from this time is the Hotel Guimard. It was built in 1909 in Paris, ten years after his success with the Castel Béranger. He built it after marrying Adeline Oppenheim, an American painter from a wealthy family.

The house was built on a challenging triangular piece of land. Guimard used an angled elevator instead of stairs on the upper floors to save space. The design showed the different uses of the house. His wife had a studio with large windows, and he had his office in another part. It had a very large dining room but no kitchen, suggesting it was for work and entertaining. The house was later divided into apartments, and the original furniture is gone.

Apartments and a Synagogue

By the 1910s, Guimard was no longer the most popular architect in Paris. But he continued to design homes, apartment buildings, and monuments. Between 1910 and 1911, he built the Hôtel Mezzara, trying out new ideas with skylights.

Another important work from this time is the Agoudas Hakehilos Synagogue in the Marais district of Paris. This was Guimard's only religious building. It has a narrow front covered in white stone, with curvy, wavy surfaces that emphasize its height. As usual, Guimard designed the inside spaces and the furniture to match the building's style. Construction began in 1913, and it opened on June 7, 1914, just before World War I started.

Later Career (1914–1942)

World War I and After

By the time First World War began in August 1914, Art Nouveau was no longer in style. The war used up most workers and building materials. Many of Guimard's projects were put on hold. He closed his furniture workshop.

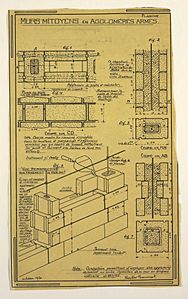

During the war, he lived outside Paris. He wrote essays about ending war and studied ideas for building cheaper, faster housing. He received several patents for his new inventions.

One of the few buildings from this time that still stands is an office building at 10 Rue de Bretagne. It was started in 1914 and finished in 1919. The Art Nouveau style was replaced by a simpler, more functional look. The building's concrete structure defined its outside. There was little decoration because materials were scarce after the war.

Just before the war, Guimard started a company to build affordable, standardized homes. He returned to Paris and built a small model house in 1921–22. However, this model was not copied. He struggled to keep up with the fast changes in styles and building methods. His company closed in 1925.

In 1925, he took part in the Paris Exposition of Decorative and Modern Arts. This exhibition gave its name to the Art Deco style. Guimard showed a model of a town hall for a French village. He also designed a parking garage and several war memorials. He continued to receive honors for his teaching. In 1929, he was made a Chevalier in the French Legion d'honneur, a high award.

After the war, Art Deco became the main style in Paris. Guimard adapted to this new style. His later buildings used geometric patterns and simpler shapes. But they still kept some of his old style, like curvy lines and plant-inspired decorations.

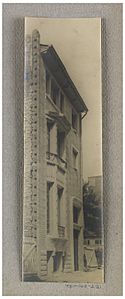

The Guimard Building and Final Works

His next big project was the Guimard Building, an apartment building started in 1926. It is his last major building that still stands. He cleverly used different colored bricks and stone to create designs on the outside. He added triangular windows on the roof. Inside, there was a remarkable central stairway with curvy iron railings and hexagonal windows made of colored glass.

In 1928, he entered this building in the same Paris competition for best facades that he won in 1898. He won again! He was the first Paris architect to win this award twice. This building became his home in 1930.

Even with this success, his later work seemed a bit old-fashioned compared to the new styles of architects like Le Corbusier. Between 1926 and 1930, he built several more residential buildings near his home. His last known work was La Guimardière, an apartment building finished around 1930. It was torn down in 1969.

As early as 1918, Guimard worked to make sure his art would be remembered. He stored models of his buildings and hundreds of designs. In 1936, he gave a large collection of his designs to Alfred Barr, the director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In September 1938, because his wife was Jewish and war was approaching, Guimard and his wife moved to New York City. He died there on May 20, 1942. He is buried in Gate of Heaven Cemetery in New York.

Obscurity and Rediscovery

After Guimard's death, many of his buildings were torn down or changed. Most of his original Metro entrances were also removed. Only the one at Porte Dauphine remained in its original spot.

However, many of Guimard's original drawings were kept in archives. His wife tried to donate the Hotel Guimard to the French state or the City of Paris as a museum, but they refused. Instead, she donated three rooms of his furniture to museums in Lyon and Paris. She also gave a collection of designs and photos to the Museum of Decorative Arts.

Guimard's work started to be appreciated again in the late 1960s. Parts of the Castel Beranger were protected as historic in 1965, and the whole building in 1989. His reputation got a big boost in 1970 when the Museum of Modern Art in New York held a large exhibition of his work. Other museums followed.

In 1978, all of Guimard's remaining Metro entrances (88 out of 167) were declared historically important. Some original and copied entrances were given to cities like Chicago. Rebuilt original entrances can be found at Abbesses and Châtelet Metro stations.

Many of his buildings have been changed, so there are no complete Guimard interiors open to the public. But you can see his furniture in museums like the Museum of Decorative Arts and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

Guimard is honored with street names in several French towns.

Furniture Designs

Like other Art Nouveau architects, Guimard also designed furniture and other decorations. He wanted them to match his buildings perfectly. It took him some time to find his unique style in furniture.

His early furniture sometimes had long, looping arms and many shelves. He didn't make much furniture for the Castel Béranger, only a desk and chairs for his own office there. He is known to have made only two full sets of furniture in his early years: a dining room set for the Castel Henriette and one for the Villa La Bluette.

Around 1903, his furniture style began to change. He started using finer woods, like pear wood, with soft colors. He simplified his designs, removing extra arms and shelves. The best examples of his later furniture are from the Hôtel Nozal (now destroyed) and the Hotel Guimard. These pieces are now in museums like the Musée des Arts Decoratifs and the Petit Palais in Paris, and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon.

-

Divan for the billiards room of pharmacist Albert Roy at Gévriles (1897-90) (Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

The Guimard Style

Much of Guimard's success came from the small details in his designs. He carefully crafted everything from door handles to balcony railings and even the letters in his signs. He created his own style of lettering for his Metro entrances and building plans. He wanted his work to be called "Style Guimard," not just Art Nouveau. He was very good at promoting his work. He wrote articles, gave interviews, and even made "Style Guimard" postcards of his buildings.

Guimard did not like the popular Beaux-Arts style of the 1880s. He called it "cold" and lacking spirit. His fellow students even nicknamed him the "Ravachol of architecture," after a famous anarchist. Still, he was recognized for his design skills. He won many awards at his school.

Guimard's early Art Nouveau work, especially the Castel Beranger, was heavily influenced by the Belgian architect Victor Horta. Like Horta, Guimard created original designs inspired by nature. He used curvy, flowing shapes that reminded him of plants and sap flowing from a tree. He called this the "sap of things."

Guimard also experimented with space and volume in his buildings. For example, the Coilliot House had a confusing double front. The Villa La Bluette was known for its balanced shapes. The Castel Henriette and Castel d'Orgeval used an "asymmetrical free plan." This was a new idea, used 25 years before Le Corbusier developed similar theories. Other buildings, like the Hôtel Nozal, used a more structured, symmetrical style inspired by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.

Guimard also used new building techniques. In the concert hall Humbert-de-Romans, he created a complex frame to improve sound quality. In the Hôtel Guimard, the ground was too narrow for the outer walls to support weight. So, the inside rooms were arranged differently on each floor.

Besides architecture and furniture, Guimard designed art objects like vases. Some of these were made by the Manufacture nationale de Sèvres, a famous porcelain factory. A notable example is the Vase of Binelles (1902), made of porcelain with unique crystal patterns.

Guimard strongly believed in making things in a standard way. He mass-produced Metro station parts and even tried to mass-produce cast iron pieces for houses. His "Artistic Cast Iron, Guimard Style" catalog offered standard iron elements for buildings. His art objects also showed this idea, combining practical use with flowing designs.

Notable Buildings Timeline

1889

- Café Au grand Neptune, Paris (destroyed around 1910)

- Pavillion d'Electricité at the Exposition Universelle (1889), Paris (destroyed 1889)

1891

- Hôtel Roszé, Paris

- Two pavilions for Alphonse-Marie Hannequin, Paris (destroyed 1926)

1892

- Villa Toucy, Billancourt (destroyed 1912–13)

- Pavillon de chasse Rose, Limeil-Brévannes (destroyed around 1960)

1893

- Hôtel Jassedé, Paris (protected)

1894

- Hôtel Delfau, Paris (modified)

1895

- École du Sacré-Coeur, Paris (modified and some demolished, protected in 1983)

1896

- Villa Berthe, Le Vésinet (protected in 1979)

- Maison de rapport Lécolle, Saint-Ouen

- La Hublotière at Vésinet

1898

- Maison Coilliot, Lille (Protected in 1977)

- Gun Shop building of Coutollau, Angers (demolished in 1919)

- Hôtel Roy, Paris (destroyed)

- Two pavilions in Hameau Boileau, Paris (heavily modified)

- Completion of Castel Béranger, Paris (partially protected in 1965, entirely in 1992)

1899

- Completion of Castel Henriette, Sèvres (destroyed 1969)

- Completion of Villa La Bluette, Hermanville-sur-Mer (Protected)

1900

- Completion of Coilliot House (Lille) (Protected 1977)

- Entrances and railings for the Paris Metro (from 1900 until 1903)

1901

- Completion of Salle Humbert-de-Romans (Paris)

1903

- Castel Val, Auvers-sur-Oise

1904

- Castel Orgeval, Villemoisson-sur-Orge (protected 1975)

1905

- Completion of the Immeuble Jassedé, Paris

1906

- Completion of Hôtel Nazal, Paris (modified 1957, destroyed 1957)

- Hôtel Deron Levet, Paris (protected 1975)

1907

- Villa La Sapinière, Hermanville-sur-Mer, Calvados (substantially remodelled)

1909

- Completion of the Hôtel Guimard, Paris (Protected 1964 and 1997)

- Immeuble Trémois, Paris

- Le Chalet Blanc, Sceaux (Hauts-de-Seine) (Protected in 1975)

1910

- Hôtel Mezzara, Paris (Protected in 1994)

1911

- Completion of four houses at Rue Fontaine and Rue Agar, Paris

1913

- Synagogue de la rue Pavée à Paris, Paris (protected in 1989)

- Villa Hemsy, Saint-Cloud (Hauts-de-Seine) (Later modified)

1914

- Completion of Hotel Nicolle de Montjoye, Paris (demolished)

1919

- Completion of an office building for Maurice Franck, Paris (begun in 1914)

1920

- Completion of a parking garage, Paris (Demolished in 1966)

1922

- Completion of a standardized model house, Paris

1923

- Completion of a Château Villa (Art Nouveau) and redesign of existing estate buildings for Emile Garnier, Quettreville-Sur-Sienne

1926

- Guimard Building, apartment building, Paris

1927

- Houyet building, Paris

1928

- Completed two apartment buildings, Paris

1930

- La Guimardière, Vaucresson, Hauts-de-Seine (Demolished March–April 1969)

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Hector Guimard para niños

In Spanish: Hector Guimard para niños

- Art Nouveau in Paris

- Paris architecture of the Belle Époque

- Paris Métro entrances by Hector Guimard

- Concours de façades de la ville de Paris (Guimard was a winner in 1898 and 1928)

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |