Victor Horta facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Victor Horta

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 6 January 1861 Ghent, East Flanders, Belgium

|

| Died | 8 September 1947 (aged 86) Brussels, (Brabant), Belgium

|

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards |

|

| Buildings |

|

| Projects | Brussels Central Station |

| Signature | |

Victor Horta (born January 6, 1861 – died September 8, 1947) was a famous Belgian architect and designer. He was one of the main people who started the Art Nouveau movement. Art Nouveau is a style of art and architecture that uses curving, natural shapes, like plants and flowers.

Horta was a big fan of a French architect named Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Horta's first Art Nouveau house, the Hôtel Tassel in Brussels (built 1892–93), was inspired by Viollet-le-Duc's ideas. The flowing, plant-like designs Horta used then influenced many other artists. For example, the French architect Hector Guimard used similar styles for the Paris Métro entrances.

Victor Horta is also seen as an early leader of modern architecture. He created open spaces inside buildings. He also used new materials like iron, steel, and glass in very creative ways.

Later in his career, Horta's style changed. It became more geometric and formal, with some classic touches like columns. He was very good at using steel frames and skylights to bring lots of light into his buildings. He also designed open floor plans and beautiful small details. Some of his important later works include the Maison du Peuple (1895–1899) and the Brussels' Centre for Fine Arts (1923–1929). He also worked on the Brussels Central Station (1913–1952). In 1932, King Albert I gave Horta the special title of "Baron" because of his great work in architecture.

After Art Nouveau became less popular, many of Horta's buildings were left empty or even torn down. However, his work is now highly valued again. In 2000, UNESCO added four of his Brussels buildings to the World Heritage List. These are the Hôtel Tassel, the Hôtel Solvay, the Hôtel van Eetvelde, and the Horta House (which is now the Horta Museum).

Contents

- Victor Horta's Early Life and Work

- The Start of Art Nouveau: Horta's Town Houses

- Hôtel Tassel: A New Style (1892–1893)

- Hôtel Solvay: Luxury and Detail (1898–1900)

- Hôtel Van Eetvelde: Light and Space (1898–1900)

- Horta House and Studio: His Own Home (1898–1901)

- Hôtel Aubecq: A Lost Masterpiece (1899–1902)

- Maison du Peuple: A Building for Everyone (1895–1899)

- Magasins Waucquez: A Textile Store Transformed (1905)

- Brugmann University Hospital: A Healing Design (1906)

- World War I and Travel to the United States

- Later Projects: A New Modern Style (1919–1939)

- Horta's Furniture Designs

- Later Life and Legacy

- Honors and Awards

- List of Victor Horta's Works

- Images for kids

- See also

Victor Horta's Early Life and Work

Victor Horta was born in Ghent, Belgium, on January 6, 1861. His father was a skilled shoemaker who believed that making things by hand was a high form of art. Young Victor first studied music at the Royal Conservatory of Ghent. He was later asked to leave because of bad behavior.

Instead, he went to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent. When he was 17, he moved to Paris. There, he found work with an architect and designer named Jules Debuysson.

In 1880, Horta's father passed away, and Victor returned to Belgium. He moved to Brussels and got married. He later had two daughters. He then started studying architecture at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. He became friends with Paul Hankar, another architect who helped start Art Nouveau.

Horta did very well in his studies. His professor, Alphonse Balat, who was the architect for King Leopold II, took Horta on as an assistant. Horta worked with Balat on the Royal Greenhouses of Laeken. This was Horta's first time using glass and iron in his designs. In 1884, Horta won the first Prix Godecharle for architecture. He won it for his idea for a new building for the Belgian Parliament. When he graduated, he received the Grand Prize in architecture.

After graduating, Horta joined the Central Society of Belgian Architecture. He designed and built three houses in a traditional style. He also took part in several design competitions. In 1892, he became the head of Graphic Design for Architecture at the Free University of Brussels. He was made a professor in 1893. Around this time, Horta learned about the British Arts and Crafts movement through talks and exhibits. This movement, especially its ideas about book design, textiles, and wallpaper, influenced his later work.

In 1893, Horta built the Autrique House for his friend Eugène Autrique. The inside of the house had a traditional layout because of a small budget. However, the outside showed some early Art Nouveau ideas. These included iron columns and ceramic flower designs. In 1894, Horta became President of the Central Society of Belgian Architecture. But he resigned the next year. This happened after he was given a job to design a kindergarten in Brussels without a public competition.

Throughout his life, Horta was greatly influenced by the French architectural thinker Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Horta completely agreed with Viollet-le-Duc's ideas.

The Start of Art Nouveau: Horta's Town Houses

Hôtel Tassel: A New Style (1892–1893)

A big moment for Horta came in 1892. He was asked to design a home for a scientist named Émile Tassel. The Hôtel Tassel was finished in 1893. The stone front of the house looked quite traditional. It was made to fit in with the buildings next to it. But the inside was completely new and exciting.

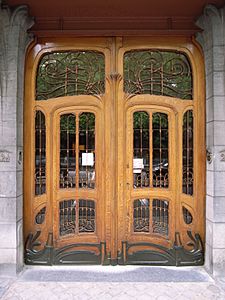

Horta used glass and iron, materials he had worked with at the Royal Greenhouses of Laeken. He used them to create an inside space full of light. The house was built around a central staircase that was open. The decorations inside had curving lines, like vines and flowers. These designs appeared on the iron railings of the stairs. They were also on the floor tiles, in the glass of the doors and skylights, and painted on the walls.

This building is often called the very first Art Nouveau building. In 2000, it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Three other houses Horta designed were also included. UNESCO said these buildings showed a "stylistic revolution." They had open plans, lots of light, and beautiful curved decorations mixed with the building's structure.

Hôtel Solvay: Luxury and Detail (1898–1900)

The Hôtel Solvay is on the Avenue Louise in Brussels. It was built for Armand Solvay, whose father was a rich chemist. Horta had a huge budget for this house. He used very special and rare materials in new ways. For example, he used marble, bronze, and rare tropical woods for the staircase.

A painter named Théo van Rysselberghe decorated the stairway walls using a style called Pointillism. Horta designed every small detail himself. This included the bronze doorbell and even the house number. Everything matched the overall Art Nouveau style of the house.

Hôtel Van Eetvelde: Light and Space (1898–1900)

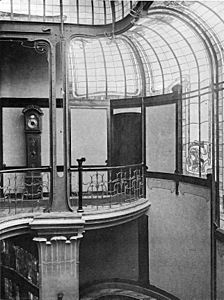

The Hôtel van Eetvelde is seen as one of Horta's most amazing and creative buildings. It has a very special Winter Garden inside and imaginative details everywhere. The open design of the Hôtel Van Eetvelde was especially new. It let in lots of light from all directions and created a feeling of great space.

A central open area went up through the whole building. This brought light from a skylight at the top. On the main floor, the oval-shaped rooms were open to this central area. They also got light from large bay windows. You could look from one side of the building to the other from any of the rooms on the main floor.

Horta House and Studio: His Own Home (1898–1901)

The Horta House and Studio is now the Horta Museum. This was where Horta lived and worked. It was simpler than his other grand houses. But it still had its own unique features and amazing craftsmanship. He used unusual mixes of materials, like wood, iron, and marble, in the staircase.

What was new about Horta's houses, and later his bigger buildings, was his goal for lots of light. He wanted buildings to be as clear and bright as possible. This was often hard to do with the narrow building plots in Brussels. He achieved this by using large windows, skylights, and mirrors. Most importantly, he used open floor plans. These plans let light come in from all sides and from above.

-

Detail of the door of the Horta Museum, Brussels (1898–1901)

Hôtel Aubecq: A Lost Masterpiece (1899–1902)

The Hôtel Aubecq in Brussels was one of Horta's later houses. He designed it for a businessman named Octave Aubecq. Like his other homes, it had a skylight over the main staircase. This filled the house with light. What made it special were the octagonal (eight-sided) rooms. It also had three sides with windows to let in the most light. The owner wanted to keep his old furniture. But because of the unusual room shapes, Horta had to design new furniture for him.

By 1948, Art Nouveau was no longer popular. The house was sold to a new owner who wanted to tear it down. People tried to save the house, but in the end, only the front (facade) and the furniture were saved by the City of Brussels. The facade was taken apart and stored. Many ideas were made to rebuild it, but none happened. Some of the furniture is now shown at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

-

Furniture from the Hôtel Aubecq at the Musée d'Orsay, Paris

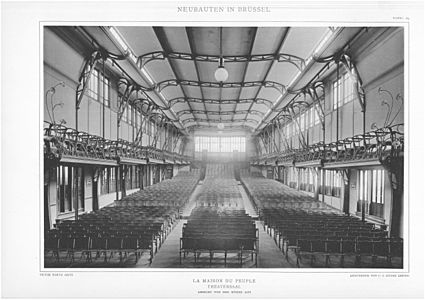

Maison du Peuple: A Building for Everyone (1895–1899)

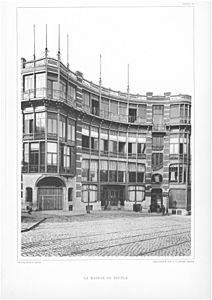

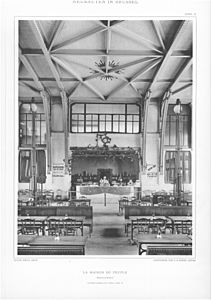

While Horta was building fancy houses for rich people, he also used his ideas for more practical buildings. From 1895 to 1899, he designed and built the Maison du Peuple ("House of the People"). This was the main office for the Belgian Workers' Party.

It was a very large building with offices, meeting rooms, a café, and a big hall for concerts and meetings that could hold over 2,000 people. It was built mainly for its purpose, using steel columns and outer walls that were like curtains. Unlike his houses, it had almost no decoration. The only Art Nouveau touch was a slight curve in the steel pillars holding up the roof. Like his houses, the building was designed to use as much light as possible. It had large skylights over the main meeting room. Sadly, it was torn down in 1965, even after many architects from around the world protested. Some parts of the building were saved to be rebuilt, but they ended up scattered around Brussels. Some pieces were even used for the Brussels Metro system.

Around 1900, Horta's buildings started to look simpler. But they were always made with great care for how they would be used and how well they were built. In 1903, he built the Grand Bazar Anspach, a large department store. It showed his usual use of big windows, open floors, and wrought iron decorations. In 1907, Horta designed the Museum for Fine Arts in Tournai. However, it didn't open until 1928 because of World War I.

Magasins Waucquez: A Textile Store Transformed (1905)

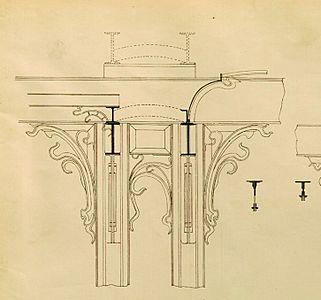

The Magasins Waucquez was once a department store that sold textiles (fabrics). Today, it is the Belgian Comic Strip Center. In its design, Horta used all his skill with steel and glass. He created amazing open spaces and filled them with light from above. The steel and glass skylight is combined with decorative touches, like classic-style columns.

After the owner, Waucquez, died in 1920, the building started to fall apart. In 1970, the store closed. Jean Delhaye, who used to work for Horta, saved the building from being torn down. Because of its link to Horta, it was made a protected historical site on October 16, 1975. Now, it's a museum about Belgian comic strips. It also has a room dedicated to Victor Horta.

Brugmann University Hospital: A Healing Design (1906)

In 1906, Horta agreed to design the new Brugmann University Hospital. This is now called the Victor Horta Site of the Brugmann University Hospital. Horta's design was planned with the ideas of doctors and hospital managers in mind. He separated the hospital's different parts into many low buildings. These buildings were spread out over an 18-hectare park-like campus. Work started in 1911. Even though it was used during World War I, the hospital officially opened in 1923. Its unique design and layout interested many medical experts in Europe. Horta's hospital buildings are still used today.

World War I and Travel to the United States

In February 1915, during World War I, Belgium was taken over. Horta moved to London. He went to a conference about rebuilding Belgium. Since he couldn't go back home, he traveled to the United States in late 1915. He gave many talks at American universities. These included Cornell, Harvard, MIT, and Yale. In 1917, he was named a special lecturer and Professor of Architecture at George Washington University.

Later Projects: A New Modern Style (1919–1939)

Horta returned to Brussels in January 1919. He sold his home and workshop. He also became a full member of the Belgian Royal Academy. After the war, money was tight, and Art Nouveau was no longer popular or affordable. From this time on, Horta's style changed. He had already been making his designs simpler. Now, he stopped using natural, curvy shapes. Instead, his designs became more geometric. He continued to use smart floor plans and the newest building technology. The Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels is an example. It's a cultural center designed in a more geometric style, similar to Art Deco.

Centre for Fine Arts: Art and Architecture (1923–1929)

Horta started planning the Centre for Fine Arts in 1919. Construction began in 1923 and finished in 1929. It was first planned to be made of stone. But Horta changed the plan to use reinforced concrete with a steel frame. He wanted the concrete to be visible inside. However, the finished look wasn't what he expected, so he had it covered.

The concert hall itself is an unusual egg shape. The building also has art galleries, meeting rooms, and other useful spaces. The building is on a tricky hillside, and it has eight levels, with much of it underground. It also had to be designed so it wouldn't block the view from the Royal Palace of Brussels, which is on the hill above it.

In 1927, Horta became the Director of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. He held this job for four years, until 1931. To honor his work, King Albert I gave Horta the title of Baron in 1932.

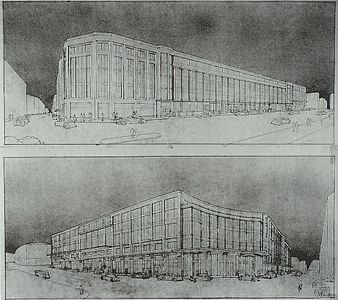

Brussels Central Station: A Long Project (1913–1952)

In 1910, Horta started drawing plans for his biggest and longest project: Brussels Central Station. He was officially hired as the architect in 1913. But work didn't actually start until after World War II, in 1952. The station was originally meant to be part of a much larger city plan Horta had thought of in the 1920s. But this bigger plan was never built.

Building the station was delayed for a long time. First, it took many years to buy and tear down over a thousand buildings along the new railway route. Then, World War I caused more delays. Construction finally began in 1937. This was part of a plan to help the economy during the Great Depression. But then World War II started, causing more delays. Horta was still working on the station when he died in 1947. His colleagues, led by Maxime Brunfaut, finished the station following Horta's plans. It opened on October 4, 1952.

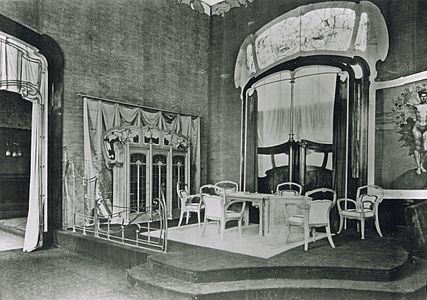

Horta's Furniture Designs

Horta usually designed not only the building itself but also the furniture inside. He made sure the furniture matched his unique style. His furniture became as famous as his houses. Some of his furniture was shown at the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris. It was also displayed at the 1902 Turin Exposition of Modern Decorative Arts.

His furniture was usually made by hand, and each piece was different for each house. In many cases, the furniture lasted longer than the house it was made for. The only downside was that since the furniture was made to fit a specific house, it couldn't be easily moved to another place. Changing it would mess up the look of the room.

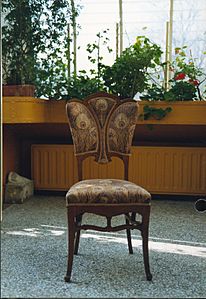

-

Peacock Chair from either the Hôtel Tassel or the Castle of La Hulpe

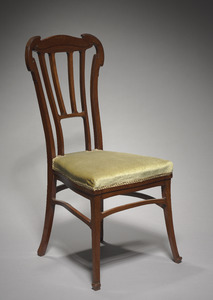

-

Mahogany chair (1900) (Cleveland Museum of Art)

-

Chair from the Hotel Aubecq (1902–04), now in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Later Life and Legacy

Horta and his first wife divorced in 1906. He married his second wife, Julia Carlsson, in 1908.

In 1925, he was an honored architect for the Belgian Pavilion at an exhibition in Paris. This exhibition gave its name to the Art Deco style. In the same year, he became the director of the Fine Arts section of the Belgian Royal Academy of Fine Arts.

In 1937, he finished the design of his last major work, Brussels Central Station. In 1939, he started writing his memories. Victor Horta passed away on September 8, 1947. He was buried in Ixelles Cemetery in Brussels.

Horta's Lasting Impact

In the 20th century, Art Nouveau became less popular. Many of Horta's buildings were left empty or even torn down. The most famous example is the Maison du Peuple, which was demolished in 1965. However, several of Horta's buildings in Brussels are still standing today. Some of them can even be visited.

The most notable surviving buildings are the Magasins Waucquez, which was once a department store and is now the Belgian Comic Strip Center. Also, four of his private houses (called hôtels) were named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000. They are known as the "Major Town Houses of the Architect Victor Horta (Brussels)":

- Hôtel Tassel, designed and built for Prof. Émile Tassel in 1892–93

- Hôtel Solvay, designed and built 1895–1900

- Hôtel van Eetvelde, designed and built 1895–1898

- House and Studio Horta, designed in 1898, now the Horta Museum, which is dedicated to his work

Honors and Awards

- 1919

- Officer of the Order of the Crown.

- Member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium

- 1920: Officer of the Order of Leopold

- 1925: Director of the Classe des Beaux-Arts of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium

- 1932: Given the title of Baron Horta by Royal Decree and granted a coat of arms

On January 6, 2015, Google Doodle celebrated his 154th birthday.

List of Victor Horta's Works

- 1885: Three houses, Twaalfkameren 49, 51, and 53, in Ghent (design)

- 1889: Temple of Human Passions, Parc du Cinquantenaire, in the City of Brussels (protected since 1976)

- 1890: Maison Matyn, Rue de Bordeaux 50, in Saint-Gilles

- 1890: Renovations and interior decoration of the residence of Henri Van Cutsem, Avenue des Arts 16, in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode (today the Charlier Museum)

- 1892–1893: Hôtel Tassel, Rue Paul-Emile Janson 6, in the City of Brussels

- 1893: Maison Autrique, Chaussée de Haecht 266, in Schaerbeek

- 1894: Hôtel Winssinger, Rue de l'Hôtel de la Monnaie 66, in Saint-Gilles

- 1894: Hôtel Frison, Rue Lebeau 37, in the City of Brussels

- 1894: Studio for the sculptor Godefroid Devreese, Rue des Ailes 71, in Schaerbeek (modified)

- 1894: Hôtel Solvay, Avenue Louise 224, in the City of Brussels

- 1895: Interior decoration of the house of the painter Anna Boch, Boulevard de la Toison d'Or 78, in Saint-Gilles (torn down)

- 1895–1898: Hôtel van Eetvelde, Avenue Palmerston 2/6, in the City of Brussels

- 1896–1898: Maison du Peuple, Place Emile Vandervelde, in the City of Brussels (torn down in 1965)

- 1897–1899: Kindergarten, Rue Sainte-Ghislaine 40, in the City of Brussels

- 1898–1900: House and Studio Horta, Rue Américaine 23–25, in Saint-Gilles (today the Horta Museum)

- 1899: Maison Frison (Les Épinglettes), Avenue Circulaire 70, in Uccle

- 1899: Hôtel Aubecq, Avenue Louise 520, in the City of Brussels (torn down in 1950)

- 1899–1903: Villa Carpentier (Les Platanes), Doorniksesteenweg 9–11, in Ronse

- 1900: Extension of the Maison Furnémont, Rue Gatti de Gamond 149, in Uccle

- 1900: À L'Innovation department store, Rue Neuve 111, in the City of Brussels (destroyed by fire in 1967)

- 1901: House and Studio for the sculptor Fernant Dubois, Avenue Brugmann 80, in Forest

- 1901: House and Studio for the sculptor Pieter-Jan Braecke, Rue de l'Abdication 51, in the City of Brussels

- 1902: Hôtel Max Hallet, Avenue Louise 346, in the City of Brussels

- 1903: Funeral monument for the composer Johannes Brahms in the Vienna Central Cemetery (with Austrian sculptor Ilse Twardowski-Conrat)

- 1903: Magasins Waucquez department store, Rue du Sable 20, in the City of Brussels (today the Belgian Centre for Comic Strip Art)

- 1903: House for the art critic Sander Pierron, Rue de l'Aqueduc 157, in Ixelles

- 1903: Grand Bazar Anspach department store, Rue de l'Evêque 66, in the City of Brussels (torn down)

- 1903: Maison Emile Vinck, Rue de Washington 85, in Ixelles (changed in 1927 by architect A. Blomme)

- 1903: À L'Innovation department store, Chausée d'Ixelles 39–51, in Ixelles (changed)

- 1904: Gym for the boarding school Les Peupliers, in Vilvoorde

- 1905: Villa Fernand Dubois, Rue Maredret, in Sosoye

- 1906: Brugmann Hospital, Place Arthur Van Gehuchten, in Jette (first design; opened in 1923)

- 1907: Magasins Hicklet, Rue Neuve 20, in the City of Brussels (changed)

- 1909: Wolfers Jewellers Shop, Rue d'Arenberg 11–13, in the City of Brussels

- 1910: House for the Dr. Terwagne, Van Rijkswijcklaan 62, in Antwerp

- 1911: Magasins Absalon department store, Rue Saint-Christophe 41, in the City of Brussels

- 1911: Maison Wiener, Avenue de l'Astronomie, in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode (torn down)

- 1912: Brussels Central Station (first designs; finished by Maxime Brunfaut and opened in 1952)

- 1920: Centre for Fine Arts, Rue Ravenstein, in the City of Brussels (first design; opened in 1928)

- 1925: Belgian pavilion at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes of Paris in 1925

- 1928: Museum of Fine Arts, in Tournai

Images for kids

-

Johannes Brahms' grave in the Vienna Central Cemetery (1903)

-

Le Grand Bazar department store, Frankfurt (1903–1905) (demolished)

-

Museum of Fine Arts, Tournai (1928)

See also

In Spanish: Victor Horta para niños

In Spanish: Victor Horta para niños

- Art Nouveau in Brussels

- History of Brussels

- Belgium in "the long nineteenth century"

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |