Persepolis facts for kids

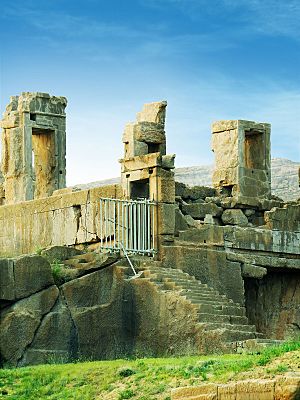

Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

|

|

| Location | Marvdasht, Fars Province, Iran |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 29°56′04″N 52°53′29″E / 29.93444°N 52.89139°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Darius I, Xerxes I and Artaxerxes I |

| Material | Limestone, mud-brick, cedar wood |

| Founded | 6th century BC |

| Periods | Achaemenid Empire |

| Cultures | Persian |

| Events |

|

| Site notes | |

| Condition | in ruins |

| Management | Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization of Iran |

| Public access | open |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Achaemenid |

| Official name | Persepolis |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, vi |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 114 |

| State Party | Iran |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

Persepolis was a very important city in ancient Persia. It was the special capital for ceremonies of the Achaemenid Empire. This empire ruled a huge area from about 550 to 330 BCE.

Persepolis is located in Iran, about 60 kilometers northeast of the city of Shiraz. The oldest parts of Persepolis were built around 515 BCE. The buildings show the unique style of Achaemenid architecture. Because of its historical importance, UNESCO made the ruins of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979. This means it's a special place protected for everyone to see.

Contents

Where is Persepolis Located?

Persepolis is built near a small river called Pulvar. This river flows into the larger Kur River.

The city sits on a huge platform that covers 125,000 square meters. Part of this platform was built by people, and part was carved out of a mountain. The east side of the platform rests against Rahmat Mountain. The other three sides have strong walls that change in height.

On the west side, there was a double staircase, about 5 to 13 meters high. This staircase gently sloped upwards. To make the platform flat, workers filled low areas with soil and heavy rocks. They joined these rocks together with metal clips.

The Story of Persepolis

Evidence from archaeologists shows that Persepolis began around 515 BC. André Godard, a French archaeologist, explored Persepolis in the 1930s. He believed that Cyrus the Great chose the spot for Persepolis. However, it was Darius I who built the main platform and palaces. Inscriptions on the buildings confirm that Darius built them.

When Darius I became king, Persepolis likely became the main capital of Persia. But it was in a remote, mountainous area. So, it wasn't always easy for the rulers to live there. Other important cities like Susa, Babylon, and Ecbatana were also capitals. This might be why the Greeks didn't know about Persepolis until Alexander the Great attacked it.

Darius I built Persepolis at the same time as his palace in Susa. Some historians believe the Susa Palace was a model for Persepolis. Darius I ordered the building of the Apadana and the Council Hall. He also started the main imperial Treasury. His son, Xerxes I, finished these buildings. Construction continued on the platform until the Achaemenid Empire ended.

Around 519 BC, workers started building a wide stairway. This stairway was meant to be the main entrance to the platform. It was about 20 meters above the ground. The double stairway, called the Persepolitan Stairway, was built on the western side. It had 111 steps, each about 6.9 meters wide. The steps were shallow, only 10 cm high. This shallow design allowed important visitors to walk up gracefully.

Grey limestone was the main material used to build Persepolis. After leveling the ground, workers dug large tunnels underground for sewage. They also carved a huge water storage tank at the foot of the mountain.

The platform was designed like a castle. Its angled walls helped defenders protect the city. An ancient writer, Diodorus Siculus, wrote that Persepolis had three walls. These walls had towers for defense. The first wall was 7 meters tall, the second 14 meters, and the third 27 meters. Today, these walls are no longer visible.

What was Persepolis Used For?

The exact purpose of Persepolis is still a bit of a mystery. It wasn't the biggest city in the empire. It seems to have been a grand place for ceremonies. It might have only been used at certain times of the year.

Many archaeologists believe it was used for celebrating Nowruz, the Persian New Year. This holiday happens in spring and is still important in Iran. During Nowruz, nobles and people from different parts of the empire would come to give gifts to the king. You can see these gift-givers in the carvings on the stairways.

How Persepolis Was Destroyed

In 330 BC, Alexander the Great invaded the Achaemenid Empire. He sent his army to Persepolis. His army had to fight through a mountain pass called the "Persian Gates". Here, a Persian leader named Ariobarzanes of Persis ambushed Alexander's army. He caused many losses. After 30 days, Alexander found a way to get around the defenders and defeated them.

After several months, Alexander allowed his soldiers to take treasures from Persepolis. Around this time, a fire burned "the palaces" or "the palace." Historians agree this fire happened at the ruins we now call Persepolis. It seems that at least one palace, built by Xerxes I, shows signs of fire damage.

Many believe the fire started in the Hadish Palace, where Xerxes I lived. Then it spread to the rest of the city. It's not clear if the fire was an accident or on purpose. Some historians think Alexander's army burned it as revenge. This was because the Persian King Xerxes had burned the Acropolis of Athens about 150 years earlier. So, the destruction of Persepolis could have been both an accident and an act of revenge.

An old Zoroastrian book, The Book of Arda Wiraz, says that Persepolis had archives with important religious texts. These texts were written on cow-skins with gold ink and were destroyed by the fire.

Interestingly, the fire might have helped save some important clay tablets. These are called the Persepolis Fortification Archive tablets. The fire caused the upper part of a wall to collapse, which then protected the tablets. They were found much later by archaeologists.

What Happened After the Empire Fell?

In 316 BC, Persepolis was still the capital of Persia, but now it was part of the Macedonian Empire. Over time, the city slowly declined. A lower city near the imperial city might have lasted longer. But the grand ruins of the Achaemenids remained as a reminder of its past glory.

Around 200 BC, the city of Istakhr, just five kilometers north of Persepolis, became important. It was the center for local governors and religious leaders. The Sasanian kings, who ruled later, carved their own sculptures and writings on the rocks nearby.

When the Muslims invaded Persia, Istakhr fought hard. It was still an important place in the early days of Islam. But its importance faded as the new city of Shiraz grew. By the 10th century, Istakhr became very small and eventually disappeared as a city.

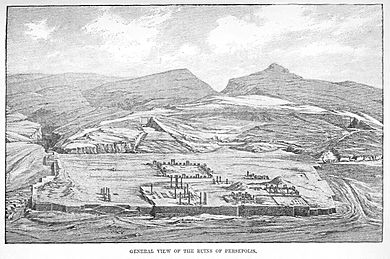

Exploring the Ruins of Persepolis

Many travelers visited Persepolis over the centuries. In 1474, Giosafat Barbaro saw the ruins but thought they were Jewish. In 1618, García de Silva Figueroa was the first Western traveler to correctly identify the site as Persepolis.

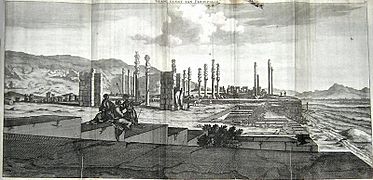

Pietro Della Valle visited in 1621. He noted that only 25 of the original 72 columns were still standing. This was due to damage or natural events. The Dutch traveler Cornelis de Bruijn visited in 1704.

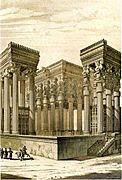

French explorers Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste were among the first to draw and describe Persepolis in detail. Their books, published in Paris in the 1880s, included 350 illustrations. These drawings helped people understand the structure of Persepolis. Later, French archaeologist André Godard became the first director of Iran's archaeological service.

In the 1800s, many people dug at the site, sometimes on a large scale. The first scientific excavations began in 1930. Ernst Herzfeld and Erich Schmidt from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago led these digs for eight seasons.

Herzfeld believed Persepolis was built to be a grand symbol of the empire. It was also a place to celebrate special events like Nowruz. It was built where the Achaemenid dynasty started, even though it wasn't the empire's main center at the time.

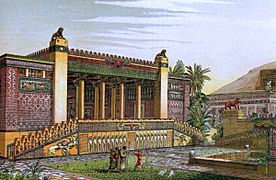

Persepolis Architecture

Persepolitan buildings are known for their unique Persian columns. These columns were likely inspired by earlier wooden ones. Architects used stone for column bases and tops. They used stone only when the largest cedar or teak trees were not big enough.

In 518 BC, many skilled engineers, architects, and artists came together. They built the first structure to symbolize unity, peace, and equality.

The buildings at Persepolis include military areas, the treasury, and royal reception halls. Important structures are the Great Stairway, the Gate of All Nations, the Apadana, and the Hall of a Hundred Columns. Other buildings include the Tripylon Hall, the Tachara, the Hadish Palace, and the Imperial Treasury.

What Remains Today

Today, you can see the ruins of many huge buildings on the platform. They are all made of dark-grey marble. Fifteen of their tall pillars are still standing. Three more pillars have been put back up since 1970. Some buildings were never finished, and you can still see leftover building materials.

More than 30,000 small inscriptions have been found at Persepolis. These short texts are very valuable documents from the Achaemenid period. Most of them show that workers in Persepolis were paid wages.

Since the time of Pietro Della Valle, it's been clear that these ruins are the Persepolis that Alexander the Great captured and partly destroyed.

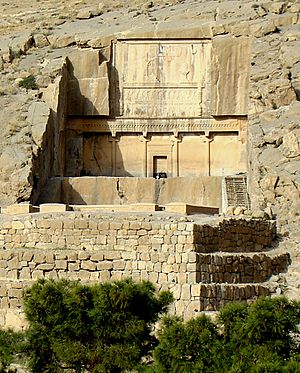

Behind the main area of Persepolis, there are three tombs carved into the rock of the hillside. Their fronts are decorated with rich carvings. About 13 kilometers north, across the Pulvar River, there's a tall rock wall. Four similar tombs are carved high up in this wall. Iranians today call this place Naqsh-e Rustam. It means "Rustam Relief," named after Sasanian carvings below the tombs. These carvings are thought to show the mythical hero Rostam.

The carvings suggest that the people buried in these seven tombs were kings. An inscription on one tomb says it belongs to Darius I. An ancient writer, Ctesias, said Darius I's grave was in a cliff and could only be reached by ropes.

-

A carving at Persepolis showing a symbol for Nowruz, the Persian New Year.

-

A carving from the Apadana showing Armenians bringing wine to the king.

-

A carving of a Median man at Persepolis.

The Gate of All Nations

The Gate of All Nations was a grand entrance for people from all over the empire. It was a large square hall, about 25 meters long, with four columns. Its main entrance was on the Western Wall. There were two other doors. One led to the Apadana yard, and the other led to a long road to the east.

Special hinges found on the doors show they were double doors. They were probably made of wood and covered with decorated metal sheets.

Two large statues of lamassus stood by the western entrance. Lamassus are mythical creatures with the body of a bull and the head of a bearded man. Another pair, with wings and a "Persian Head," stood by the eastern entrance. These statues showed the power of the empire. The name of Xerxes I was carved on the entrances in three languages. This told everyone that he ordered the gate to be built.

The Apadana Palace

Darius I built the largest palace at Persepolis on the western side of the platform. This palace was called the Apadana. The King of Kings used it for important meetings. Construction started in 518 BC, and his son, Xerxes I, finished it 30 years later.

The palace had a huge square hall, 60 meters on each side. It had 72 columns, and 13 of them still stand today. Each column is 19 meters high. The tops of the columns were carved into animal shapes, like two-headed lions, eagles, or human-headed bulls. These animals were symbols of power and good fortune. The columns supported a very large and heavy roof. The roof beams were made of oak and cedar wood brought from Lebanon.

The walls were covered with a layer of mud and stucco. This layer was then covered with a greenish stucco, which is seen throughout the palaces.

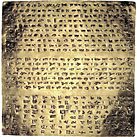

Workers found gold and silver tablets in two special boxes in the palace's foundations. These tablets had an inscription by Darius in Old Persian cuneiform. It described how vast his empire was. This inscription is known as the DPh inscription.

Darius the great king, king of kings, king of countries, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenid. King Darius says: This is the kingdom which I hold, from the Sacae who are beyond Sogdia, to Kush, and from Sind (Old Persian: 𐏃𐎡𐎭𐎢𐎺, "Hidauv", meaning "Indus valley") to Lydia (Old Persian: "Spardâ") - [this is] what Ahuramazda, the greatest of gods, bestowed upon me. May Ahuramazda protect me and my royal house!

—DPh inscription of Darius I in the foundations of the Apadana Palace

The palace had three rectangular porticos on its western, northern, and eastern sides. Each portico had twelve columns. To protect the roof from rain, vertical drains were built into the brick walls. Four towers were built at the corners of the Apadana, facing outwards.

The walls were decorated with tiles and pictures of lions, bulls, and flowers. Darius ordered his name and empire details to be written on gold and silver plates. These plates were placed in stone boxes under the palace's foundations.

Two grand stairways were built on the northern and eastern sides of the Apadana. They were symmetrical and helped connect to the stone foundations. Two other stairways were in the middle of the building. The outside of the palace was carved with images of the Immortals. These were the king's special guards. Darius I finished the northern stairway. The other stairway was finished much later.

The carvings on the staircases show people from all over the empire. You can see their traditional clothes and even the king himself in great detail.

-

Carvings of trees and lotus flowers at the Apadana.

Apadana Palace Coins

A collection of coins, called the Apadana hoard, was found under the stone boxes in the Apadana Palace. These coins were discovered in 1933 by Erich Schmidt. The coins were placed there around 515 BCE.

The hoard included eight gold Croeseids, a tetradrachm from Abdera, a stater from Aegina, and three double-sigloi from Cyprus. The Croeseids looked very new. This suggests they were recently made under Achaemenid rule. The hoard did not have any Darics or Sigloi, which were common Achaemenid coins. This means these coins probably started to be made later, after the Apadana Palace was built.

The Throne Hall

Next to the Apadana is the Throne Hall. It's the second-largest building on the platform. It's also called the Hall of Honor or the Hundred-Columns Palace. Xerxes I started this 70x70 square meter hall. His son, Artaxerxes I, finished it by the end of the fifth century BC.

Its eight stone doorways are decorated with carvings. On the south and north, they show throne scenes. On the east and west, they show the king fighting monsters. Two huge stone bulls stand at the northern entrance. The head of one of these bulls is now in the Oriental Institute in Chicago.

When Xerxes I first became king, the Throne Hall was used for welcoming military leaders. It also hosted representatives from all the nations under the empire's rule. Later, the Throne Hall became like an imperial museum.

Other Palaces and Buildings

Other important palaces include the Tachara, built by Darius I. The Imperial Treasury was also started by Darius I in 510 BC and finished by Xerxes I in 480 BC. The Hadish Palace of Xerxes I is on the highest part of the platform.

The Council Hall, the Tryplion Hall, and other palaces are also part of Persepolis. There were also storerooms, stables, and living quarters. An unfinished gateway and other structures are near the southeast corner of the platform.

Royal Tombs

Most people agree that Cyrus the Great was buried in Pasargadae, his own city. If Cambyses II's body was brought back to Persia, his tomb must be near his father's. It was a custom for kings to prepare their own tombs while they were alive.

So, the kings buried at Naqsh-e Rostam are likely Darius I, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II. The two finished tombs behind Persepolis probably belong to Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III. There is also an unfinished tomb about a kilometer from the city. People debate who it belongs to. It might be for Artaxerxes IV or Darius III. Since Alexander the Great is said to have buried Darius III at Persepolis, it's possible this unfinished tomb is his.

Persepolis Today

In 1971, Persepolis was the main site for the 2,500 Year Celebration of the Persian Empire. This event was held under the Pahlavi dynasty. It brought together people from many countries to celebrate Iranian culture and history.

Persepolis in Museums Around the World

A carving from Persepolis is in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England. The largest collection of carvings is at the British Museum. These were collected by British travelers in the 1800s. The Persepolis bull at the Oriental Institute in Chicago is a very important treasure. It came from the excavations in the 1930s.

New York City's Metropolitan Museum also has objects from Persepolis. So does the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. The Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon and the Louvre in Paris also display items from Persepolis. In 2018, a carving of a soldier that was taken from the site in the 1930s was returned to Iran.

-

The Forgotten Empire Exhibition at the British Museum.

-

A Persepolis carving at the Forgotten Empire Exhibition, British Museum.

-

A Persepolitan rosette carving at the Oriental Institute.

Views from Above

Images for kids

-

Darius the Great, painted by Eugène Flandin (1840).

-

A bust of Alexander the Great at the British Museum in London.

-

The Tomb of Artaxerxes II at Persepolis.

-

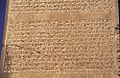

The Babylonian version of an inscription by Xerxes I, called the "XPc inscription."

See also

In Spanish: Persépolis para niños

In Spanish: Persépolis para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |